Another element that the gospels and ancient fiction have in common is the trope of the innocent hero who is ordered to be crucified by an innocent/ignorant/unjust ruler but who nonetheless survives.

Another element that the gospels and ancient fiction have in common is the trope of the innocent hero who is ordered to be crucified by an innocent/ignorant/unjust ruler but who nonetheless survives.

The silent victim

The first instance comes from the same novel that contained the empty tomb adventure, Chaereas and Callirhoe. The chief victim is silent.

They were brought out chained together at foot and neck, each carrying his cross — the men executing the sentence added this grim public spectacle to the inevitable punishment as an example to frighten the other prisoners. Now Chaereas said nothing when he was led off with the others, but Polycharmus, as he carried his cross, said: “Callirhoe, it is because of you that we are suffering like this! You are the cause of all our troubles!” (4.2)

The king changes his mind and orders Chaereas to be taken down from the cross.

This story was greeted with tears and groans, and Mithridates sent everybody off to reach Chaereas before he died. They found the rest nailed up on their crosses; Chaereas was just ascending his. So they shouted to them from far off. “Spare him!” cried some; others, “Come down!” or “Don’t hurt him!” or “Let him go!” So the executioner checked his gesture, and Chaereas climbed down from his cross — with sorrow in his heart, for he was glad to be leaving a life of misery and ill-starred love. As he was being brought, Mithridates met him and embraced him. “My brother, my friend!” he said. “Your silence almost misled me into committing a crime! Your self-control was quite out of place!” Straightaway he told his servants to take them to the baths and see to their physical well-being, and when they had bathed, to give them luxurious Greek clothes to wear. He himself invited men of rank to a banquet and offered sacrifice for Chaereas’s rescue. They drank deep, and there was generous hospitality and cheerful rejoicing. (4.3)

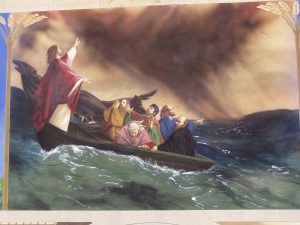

Prayer for salvation from the cross

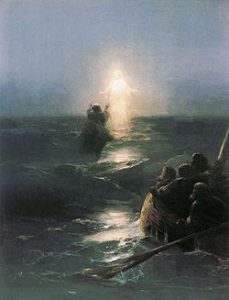

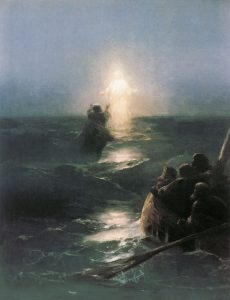

In another novella, An Ephesian Tale by Xenophon of Ephesus, another injustice is done by the ruler and an innocent man is ordered crucified. The hero prays from the cross and the god miraculously rescues him — twice, actually.

Meanwhile Habrocomes came before the prefect of Egypt. The Pelusians had made him a report of what had happened, mentioning Araxus’s death and stating that Habrocomes, a household slave, had been the perpetrator of so foul a crime. When the prefect heard the particulars, he made no further effort to find out the facts but gave orders to have Habrocomes taken away and crucified. Habrocomes himself was dumbfounded at his miseries and consoled himself at his impending death with the thought that Anthia, so it seemed, was dead as well. The prefect’s agents brought him to the banks of the Nile, where there was a sheer drop overlooking the torrent. They set up the cross and attached him to it, tying his hands and feet tight with ropes; that is the way the Egyptians crucify. They then went away and left him hanging there, thinking that their victim was securely in place. But Habrocomes looked straight at the sun, then at the Nile channel, and prayed: “Kindest of the gods, ruler of Egypt, revealer of land and sea to all men: if I, Habrocomes, have done anything wrong, may I perish miserably and incur an even greater penalty if there is one; but if I have been betrayed by a wicked woman, I pray that the waters of the Nile should never be polluted by the body of a man unjustly killed; nor should you look on such a sight, a man who has done no wrong being murdered on your territory.” The god took pity on his prayer. A sudden gust of wind arose and struck the cross, sweeping away the subsoil on the cliff where it had been fixed. Habro- comes fell into the torrent and was swept away; the water did him no harm; his fetters did not get in his way; nor did the river creatures do him any harm as he passed, but the current guided him along. He was arrested him and took him before the prefect as a fugitive from justice. He was still angrier than before, took Habrocomes for an out-and-out villain, and gave firm orders to build a pyre, put Habrocomes on it, and bum him. And so everything was made ready, the pyre was set up at the delta, Habrocomes was put on it, and the fire had been lit underneath. But just as the flames were about to engulf him, he again prayed the few words he could to be saved from the perils that threatened. Then the Nile rose in spate, and the surge of water struck the pyre and put out the flames. To those who witnessed it the event seemed like a miracle: they took Habrocomes and brought him before the prefect, told him what had happened, and explained how the Nile had come to his rescue. He was amazed when he heard what had happened and ordered Habrocomes to be kept in custody, but to be well looked after till they could find out who he was and why the gods were looking after him like this. (4.2)

Mocking procession

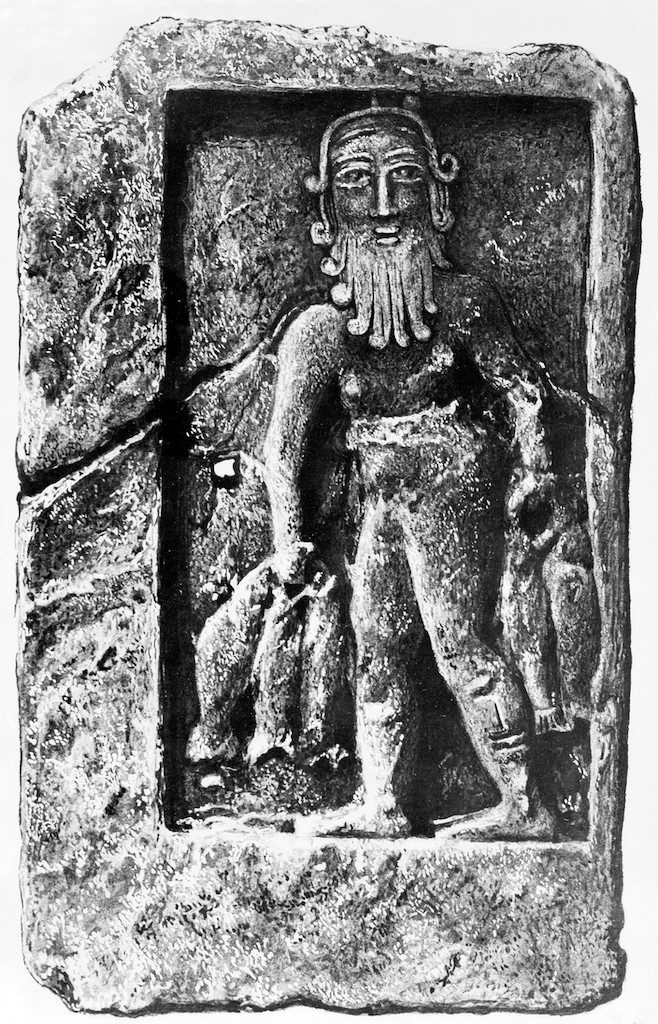

We only have an ancient summary of A Babylonian Story (by Iamblichus). It reads like a set of notes for a story to be fleshed out at a later time. It begins with a summary of the plot:

The characters in the story are the attractive Sinonis and Rhodanes, who are joined by the mutual ties of love and marriage, and the Babylonian king Garmus. After the death of his wife, he falls in love with Sinonis and is eager to marry her. Sinonis refuses and is bound in gold chains. The king’s eunuchs Damas and Sacas are given the task of putting Rhodanes onto a cross for this reason. But through Sinonis’s efforts he is taken down, and they each avoid their fate, he of crucifixion, she of marriage.

The mocking procession to the crucifixion:

When Soraechus was being taken to be crucified, Rhodanes was being led to and hoisted onto the cross that had been designated for him earlier by a garlanded and dancing Garmus, who was drunk and dancing round the cross with the flute players and reveling with abandon.

The king orders the hero to be taken down from the coss and appoints him general of his army:

While this is happening, Sacas informs Garmus by letter that Sinonis is marrying the youthful king of Syria. Rhodanes rejoices up high on the cross, but Garmus makes to kill himself. He checks himself, however, and brings down Rhodanes from the cross against his will (for he prefers to die); he appoints him general and sends him to command his army . . . .

Reardon, Bryan P., ed. 1989. Collected Ancient Greek Novels. Berkeley: University of California Press.