Some interesting points I came across while reading A. J. Woodman’s Rhetoric in Classical Historiography and some of his references:

Initial eyewitness claims not followed up

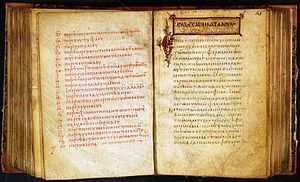

Earlier in this same chapter Thucydides drew a distinction between events which he experienced himself and those which were reported to him by others (22.2). Although he never gives us any indication of how many, or indeed which, events fall into each category . . .

(p. 26)

The implication is that Thucydides’ rhetoric is designed to impress; there is no evidence of any truth to the claim. Indeed, works demonstrating Thucydides’ reliance upon literary sources (e.g. Aeschylus, Euripides, Aristarchus of Syracuse) — sources that Thucydides attempted to deny — are listed. That reminded me that we never read in Luke-Acts which events are derived from the “eyewitnesses” apparently referenced in the prologue.

Poetic devices appearing in prose

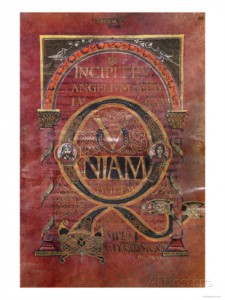

Herodotus often echoes the rhythms of poetry, and some passages of his prose can actually be turned into verse without too much difficulty. . . . . [Thucydides] . . . concludes, perhaps significantly, by reproducing the hexameter rhythm of an all but complete line of epic verse.

(pp. 3, 9)

Prose authors periodically break into poetic rhythms. That makes me wonder if there are similar practices in philosophical or epistolary literature from the era of the Pauline letters. Paul is sometimes said to be incorporating earlier hymn verses into his letters; what is the likelihood he authored such passages himself?

Grounds for suspecting interpolation

To be considered for inclusion in the category of ancient interpolations in Aristophanes a word, phrase or passage must satisfy two conditions: first, there must be grounds for thinking that Aristophanes did not write it, or at least not with the intention that it should stand where it now stands in the text; and secondly, there must be grounds for thinking that it was present in at least one copy of the text earlier than the dark age which separates late antiquity from the Photian renaissance.

Sounds reasonable. The criteria would open floodgates of possible interpolations into the NT texts, though.

Dover, Kenneth J. 1977. “Ancient Interpolation in Aristophanes.” Illinois Classical Studies 2: 136–62.

Woodman, A. J. 2004. Rhetoric in Classical Historiography: Four Studies. London : New York: Routledge.