This post continues my thoughts on a case for the non-historicity of Jesus that I began with these posts:

- Jesus Mythicism and Historical Knowledge, Part 1: Historical Facts and Probability

- Jesus Mythicism and Historical Knowledge, Part 2: Certainty and Uncertainty in History

- Jesus Mythicism and Historical Knowledge, Part 3: Prediction and History

- Jesus Mythicism and Historical Knowledge, Part 4: Did Jesus Exist?

And two related afterthoughts to the above:

Since I began drafting this post, Richard Carrier has responded specifically to some of my subsequent comments that were made in an exchange over what I, rightly or wrongly, understood to be some confusion about my view of Bayes’ theorem. He has not, as far as I see — again, I am open to correction and reminding — responded to the central argument of these posts. Further, I began posting a detailed review (scroll to bottom of the page for the reviews) of Carrier’s Proving History in 2012 but other questions arose that distracted me from that project after three posts. This series might be seen as an update on my views of Carrier’s application of Bayes’ theorem to history generally and Jesus in particular.

My position on the historical Jesus

To begin with, I think the only figures of Jesus of any relevance to the historian are

- the Jesus in our early sources (especially the New Testament writings)

- and the political shapes of Jesus through the ages.

Attempting to “discover” a Jesus “behind” the sources through memory theory or other means (criteria of authenticity, form criticism) necessarily begins with the assumption that the stories told in the gospels have some kind of relationship with a historical Jesus. In other words, they assume a historical figure was the starting point of everything. (A passage found in a work by the Jewish historian Josephus, even if only partially authentic, can tell us nothing more than what was being said about Jesus some sixty years after he was supposed to have lived.)

My position regarding Bayes’ Theorem

One more point I should reiterate. I have said many times now that Bayes’ theorem is a fine tool to apply to many hypotheses. My point, though, is that I see little historical value in hypothesizing the existence or non-existence of Jesus per se. What is of historical interest is how Christianity emerged. A hypothetical Jesus or hypothetical non-Jesus alone doesn’t help us with that question. We simply don’t know if there was a figure identifiable as Jesus at or near the start of Christianity. The reason we do not know arises from the lack of independent and empirical data to establish his presence. Historical explanations can draw on hypothetical scenarios but when they do they can never be more than hypothetical proposals. I prefer that a historian works more modestly with what can be securely known and seeks to explain that much.

My position with respect to Richard Carrier’s historical methods

When Richard Carrier’s books Proving History and On the Historicity of Jesus first appeared I was intrigued by the Bayesian approach and in large measure rode with it. But what especially attracted me was the comprehensiveness of Carrier’s approach to the question that had at that time been a “hot topic” ever since Earl Doherty’s contributions. At the time I attempted to shelve some discomfort I felt over Carrier’s portrayal of “what historians do” and “how they do things” more generally. He seemed to me to be returning to a positivist view of history, a view that had largely been left in the margins especially since the mid twentieth century. One other discomfort I had was that I thought he was weakening his position and making himself too-easy-a-target for critics by adding new speculative arguments to those of Earl Doherty. I felt a stronger case and smaller target would have been made with less rather than more — with zeroing in on a selection of core arguments from Doherty rather than trying to cover everything that had been argued and adding even to that.

Though I have written many posts in favour of the application of Bayes’ Theorem to questions arising in biblical studies (and I have Richard Carrier to thank for introducing me to the usefulness of Bayes) I have also found myself in disagreement with some of Carrier’s views:

Ironically, in most of those cases, I think that it is Carrier who has dropped the Bayesian ball along with “rational-empirical” argument and it is yours truly who is using Bayesian reasoning to demonstrate where some of Carrier’s views are amiss.

At the time I held back my criticisms mainly because I did not want to be seen as part of what was then a hostile internet backlash against Carrier. But since I have recently been deeply re-engaging with the nature of historical knowledge and history itself I have felt the time is right to try to resolve some issues raised by Carrier’s work that originally left me a little uncomfortable.

Misapplied Conclusions from Bayesian Analysis

If we conclude from Bayesian reasoning that a historical Jesus is not likely to have existed, it tells us nothing useful. All it would mean is that if Jesus did exist there were many views expressed about him that gave rise to suspicions about his existence among later readers. He would not be the first.

No historical event is the same as another and no historical person is the same as another. Each and every historical event and historical person and circumstance is unique in some way. Hypotheses about the existence or non-existence of Jesus are hypotheses about a unique event.

But it is impossible to compute the frequencies of events that are unique. (Tucker, 136 — Tucker further notes, without comment, Carrier’s response to this problem, which is to assign a range of probabilities including subjective but informed probability estimates of experts — that is, measuring )

A Case Study

Carrier argues that even subjective expectations are ultimately (though perhaps hidden from one’s immediate consciousness) based on calculable frequencies of the same kinds of events:

Any time you talk about degrees of belief or certainty, just think about what you base that judgment on, and what facts would change your mind. Always at root you will find some sort of physical frequency that you were measuring or estimating all along. (272)

I am not so sure. Are “degrees of belief” or subjective “certainty” always or necessarily based on conscious or subconscious rational calculation? If so, there can be no such thing as “subjective” belief: every belief would be at some level a rational calculation based on relevant frequencies. I am not as confident as Carrier in the fundamental rationality of all subjective beliefs and expectations.

Let’s take a unique historical event, one that Carrier discusses in Proving History, and examine his argument. The historical hypothesis here is that Henry I plotted to kill William II.

In our personal correspondence, C. B. McCullagh observed that to apply BT to questions in history

the hypothetical event has to be considered as a generic type, similar in some respect to others. That might worry historians, whose hypotheses are so often quite particular. For instance, consider how the hypothesis that Henry planned to kill William II in order to seize his throne explains the fact that after his death Henry quickly seized the royal treasure. The relation between these events is rational, not a matter of frequency. . . . (The example being referred to is discussed in C. Behan McCullagh, Justifying Historical Descriptions (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984), p. 22.)

But, in fact, if the connection alleged is rational, then by definition it is a matter of frequency, entailed by a hypothetical reference class of comparable scenarios. To say it is rational is thus identical to saying that in any set of relevantly similar circumstances, most by far will exhibit the same relation. If we didn’t believe that (if we had no certainty that that relation would frequently obtain in any other relevantly similar circumstances), then the proposed inference wouldn’t be rational. Explaining why confirms the point that all epistemic probabilities are approximations of physical frequencies. The evidence in this case is that Henry not only seized the royal treasure with unusual rapidity, but that his succeeding at this would have required considerable preparations before William’s death, and such preparations entail foreknowledge of that death. Already to say Henry seized the royal treasure “with unusual rapidity” is a plain statement of frequency, for unusual = infrequent, and this statement of frequency is either well-founded or else irrational to maintain. And if that frequency is irrational to maintain, we are not warranted in saying anything was unusual about it. Likewise, saying “it would have required considerable preparations” amounts to saying that in any hypothetical set of scenarios in all other respects identical, successful acquisition of the treasure so quickly will be infrequent, and thus improbable, unless prior preparations had been made (in fact, if it is claimed such success would have been impossible without those preparations, that amounts to saying no member of the reference class will contain a successful outcome except members that include preparations). Again, the result is said to be unusual without such preparations, or even impossible; and unusual = infrequent, while impossible = a frequency of zero. Hence such a claim to frequency must already be defensible or it must be abandoned. Similarly for every other inference: making preparations in advance of an unexpected death is inherently improbable for anyone not privy to a conspiracy to arrange that death, and being privy to such a conspiracy is improbable for anyone not actually part of that conspiracy, and in each case we have again a frequency: we are literally saying that in all cases of foreknowing an otherwise unpredicted death, most of those cases will involve prior knowledge of a planned murder, and in all cases of having foreknowledge of a planned murder, few will involve people not part of that plan. If those frequency statements are unsustainable, so are the inferences that depend on them. And so on down the line.

Thus even so particular a case as this reduces to a network of generalized frequencies. And all our judgments in this case necessarily assume we know what those frequencies are (with at least enough accuracy to warrant confidence in the conclusion). We won’t know exactly the frequencies involved, but we know they must be generally in the ballpark stated, otherwise we wouldn’t be making a rational inference at all. (273f – my highlighting in all quotations)

Here Carrier notes as background knowledge that “considerable preparations” would have been required “before William’s death” for Henry’s actions to have succeeded. He confuses this background knowledge with “evidence” but understanding the complexities involved in asserting full control of the royal treasure is really background knowledge. That background knowledge forms the basis of the hypothesis that Henry murdered William. Carrier leaves this aside. He suggests that Henry’s ‘unusual rapidity’ in taking control reflects subconscious knowledge of how infrequently such events occur under normal circumstances. But I do not know how Carrier could verify that historians really do reflect on how many times a royal treasure has been taken over with such speed, or how often comparable “classes of events” have occurred. Carrier does not give examples of similar “reference class acts” with which to compare and I suspect most historians will need time to think before they could offer instances. Even if one did compile a list of comparable successions in an attempt to establish a reference class with which to compare Henry’s succession of William, historians would be hard pressed to tease out all factors that made each situation unique and to justify its relevance to the particular event of Henry’s replacement of William. Rather, it is simpler and more likely that historians who are informed of the political structures and scale of England at the time use that background knowledge to infer that the speed of Henry’s acts points to the likelihood of murder.

While typing up this post I was distracted by a news item about a woman being interviewed who said that she was told she had a “only a 10%” chance of contracting a certain terminal illness but now she had it. There was no longer any 10% business about it. Statistics and probabilities are relevant when dealing with effectively infinite numbers of factors. But historical contingency is not a probability event. It happens to a particular person with a certainty of 1 regardless of what the odds are in an infinite universe and there was no way to estimate in advance that that particular woman was going to get the illness. That that unfortunate person was part of a 10% subset within a population of many thousands was meaningless to her and her loved ones. A science body had produced statistics. This person experienced an historical event. Most historical events are unforeseen — except, as I keep saying, in hindsight.

Confusing History with Science

Geology and paleontology, for instance, are largely occupied with determining the past history of life on earth and of the earth itself, just as cosmology is mainly concerned with the past history of the universe as a whole. . . .

History is the same. The historian looks at all the evidence that exists now and asks what could have brought that evidence into existence. . . .

And just as a geologist can make valid predictions about the future of the Mississippi River, so a historian can make valid (but still general) predictions about the future course of history, if the same relevant conditions are repeated (such prediction will be statistical, of course, and thus more akin to prediction in the sciences of meteorology and seismology, but such inexact predictions are still much better than random guessing). Hence, historical explanations of evidence and events are directly equivalent to scientific theories, and as such are testable against the evidence, precisely because they make predictions about that evidence. . . .

[T]he logic of their respective methods is also the same. The fact that historical theories rest on far weaker evidence relative to scientific theories, and as a result achieve far lower degrees of certainty, is a difference only in degree, not in kind. Historical theories otherwise operate the same way as scientific theories, inferring predictions from empirical evidence—both actual predictions as well as hypothetical. Because actual predictions (such as that the content of Julius Caesar’s Civil War represents Caesar’s own personal efforts at political propaganda) and hypothetical predictions (such as that if we discover in the future any lost writings from the age of Julius Caesar, they will confirm or corroborate our predictions about how the content of the Civil War came about) both follow from historical theories. This is disguised by the fact that these are more commonly called ‘explanations.’ But theories are what they are. (46ff)

I have recently addressed historical positivism at

- …. Fact and Opinion in History,

- …. Fundamentals of Doing History,

- and very briefly in …. Uncertainty in History.

What Carrier is describing here is a “positivist” view of history. This is a notion of history that was more widespread up to the middle of the last century. One of its leading exponents was Hempel who argued that historians should be seeking to discover predictable cause-effect relationships. (Hempel took positivism a step further than Carrier by claiming actual “laws” in history could be found.) His colleague, Carnap, stressed the importance of probabilistic reasoning in such an endeavour. The view that history could aspire to be akin to the natural sciences in method grew out of the Enlightenment when there was burgeoning confidence that Reason and Empiricism could liberate humanity from the shackles of superstition and dogma. But positivist history has long since been under strong attack from many quarters.

It is this positivist approach to history that explains the relevance of Carrier’s use of Reference Class. The idea of a reference class is to generalize historical events or incidents so that they can be compared with one another as a common type. That means they are temporarily removed from their historical contingency and treated as sharing common features for the sake of comparison. The point is to isolate generalized cause-effect principles.

Strictly speaking, prior probability is the probability of getting a specific kind of h when you draw at random from a reference class of all possible h → e [hypothesis to evidence] correlations. Those correlations don’t have to be causal, although in history they usually are. Because, in history, we are almost always asking what caused e and proposing h as the answer (see chapters 2 and 3). I’ll thus focus mainly on causal hypotheses and explain how to ascertain prior probabilities in a way that can produce intersubjective agreement among expert historians, and when and why such a process is logically valid. Some critics of BT are skeptical of causal language in applying the theorem, but that’s fundamental to many theories, especially historical ones, since any statement about what happened in history reduces to a statement about what caused the evidence we have. And you can’t propose historical explanations without proposing causes. Historians do distinguish claims about what happened (or once existed) from claims about why it happened (or why it existed). But ultimately all claims about ‘what’ entail claims about ‘why.’ (229)

I pause and ask if that is so. Many historians may agree with the above, but even among those who do, I think most would be sceptical about any attempt to assess varying degrees of causal probability to any of the factors associated with an event. Understanding human behaviour is not so mechanical an enterprise. The example Carrier offers does to me come across as unrealistically mechanically causal and even positivist with a vengeance:

. . . a hypothesis that a religious riot was caused by prior beliefs of that community (such as an ancient prophecy) in conjunction with new events (such as the appearance of a comet) obviously proposes a causal relationship between those prior beliefs and the riot . . . (230)

Such a view of human nature in general and historical events in particular is not one I share. I doubt that many historians have ever concluded that there can ever be such a simplistic one-to-one cause-effect of a riot as “a belief” of some kind. I propose that where riots occur a range of conditions will normally be found to help us understand the what and the why.

I think the principle applies to most works of historians today. Few, I believe, would think they can reduce historical events to isolated or particular combinations of specific causes each bearing a certain probability factor in the final equation.

In another instance, this time in On the Historicity of Jesus, Carrier continues the same refrain: the existence of prophecies would in effect have caused would-be messiahs to seek martyrdom, so in such a context, Christianity “almost becomes predictable”.

God had promised that the Jews would rule the universe (Zech. 14), but their sins kept forestalling his promise (Jer. 29; Dan. 9), which would also create a motive for would-be messiahs to perform atonement acts, which could include substitutionary self-sacrifice (see Element 43), out of increasing desperation (Elements 23-26). Christianity almost becomes predictable in this context. (OHJ 71)

Admittedly Carrier relegates this statement to a footnote but it does further illustrate the simplistic cause-effect positivism approach he has to the question of Christian origins: prophecy — would have inspired (caused) — would be prophets — to do an atonement act like Jesus — Christianity conceptually predictable (law of cause and effect) in such a scenario. If there were historically verifiable prophets acting that way, most historians would prefer to seek a deeper understanding about why such behaviour emerged at that time and place than the mere existence of a prophecy rolled away in the scrolls.

A recent work of history that I read is Killing for Country by David Marr. Along with Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland and Libby Connor’s Warrior, I have been left with a deep sense of shame about white treatment of the indigenous population of my state and a strong political and social conviction of what we owe their survivors. Those historical works were not about “cause and effect” but about understanding and awareness. There will always be causal elements in any explanation but causes per se are not always what history is about.

A recent work of history that I read is Killing for Country by David Marr. Along with Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland and Libby Connor’s Warrior, I have been left with a deep sense of shame about white treatment of the indigenous population of my state and a strong political and social conviction of what we owe their survivors. Those historical works were not about “cause and effect” but about understanding and awareness. There will always be causal elements in any explanation but causes per se are not always what history is about.

Reference Class Revisited

As far as I understand Carrier’s approach, he introduces Reference Class in the question of the historicity of Jesus in order to establish a prior notion of how likely a certain idea of Jesus is the result of a generalized cause-effect class of events. This is an attempt, as I understand it, to introduce some kind of “scientific” validity to the study of history. If we understand the “scientific” approach as one that seeks to establish the general from the particular, this is the intended function of assigning Jesus to the Rank-Raglan hero class and drawing probabilistic inferences based on cause-effect principles found in that class.

The idea is that among figures found in a subset of the Rank-Raglan class few or none are known to be historical. The principle Carrier wants us to conclude from this is that stories of a certain type are “caused” by something other than a historical figure behind them.

If therefore we find Jesus within this subset of story types, then it logically follows that those stories about him likewise owe their existence to something other than an actual historical figure of Jesus.

I agree that in principle — and it is the principle that counts — that is a correct conclusion. Lord Raglan himself expressed the same point:

If, however, we take any really historical person, and make a clear distinction between what history tells us of him and what tradition tells us, we shall find that tradition, far from being supplementary to history, is totally unconnected with it, and that the hero of history and the hero of tradition are really two quite different persons, though they may bear the same name. (The Hero, 165)

Further, I think a good many biblical scholars will also agree that what we read in the gospels about Jesus is in large measure unconnected with a historical Jesus. Many argue that the stories that arose about Jesus were fabricated to meet the needs of later generations.

In other words, the reference class itself is irrelevant to the question of the historicity of Jesus. It is a misguided attempt to establish a quasi-scientific or positivist approach to history by establishing a principle that transcends the uniqueness of each historically contingent event and person.

The mythical stories about Jesus tell the historian something important to the interests of early Christianities but as Lord Raglan pointed out by implication — those stories of themselves cannot have any relevance to the question of whether there was some kind of historical Jesus at the start of it all. If we think otherwise we would need to argue the case with evidence.

Of course, many other biblical scholars are quick to deny this point and will claim “memory theory” and “triangulating” “gists” of gospel stories and sayings can help them see “through a glass darkly” some outline of the historical Jesus. But such notions are founded entirely on the assumption that Lord Raglan was wrong and that the stories did evolve from a historical person.

We simply have no way of knowing if “a historical Jesus” existed. There are many interesting studies that explain the New Testament sources emerging from within the historical, philosophical and literary milieu of the day without appealing to a hypothetical role for a historical Jesus. We don’t need to over-reach and try to “prove” anything within any margin of probability. Hypothetical notions relating to the existence or nonexistence of Jesus cannot help the historian produce any serious reconstruction or understanding of Christian origins. Let’s be content with what we cannot know and focus on what we do know. Carrier’s On the Historicity of Jesus, especially its Backgound/Context section, offers many areas for further study. As I pointed out above, I think there are some areas where even Carrier can more consistently and profitably apply Bayesian analysis.

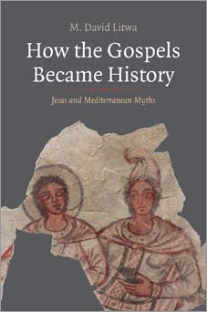

Carrier, Richard. Proving History: Bayes’s Theorem and the Quest for the Historical Jesus. Amherst, N.Y: Prometheus Books, 2012.

Carrier, Richard. On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2014.

Tucker, Aviezer. “The Reverend Bayes vs. Jesus Christ,” History and Theory 55, no. 1 (February 1, 2016): 129–40.