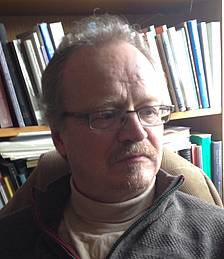

The focus of my response will center on Carrier’s

- claim that a pre-Christian angel named Jesus existed,

- his understanding of Jesus as a non-human and celestial figure within the Pauline corpus,

- his argument that Paul understood Jesus to be crucified by demons and not by earthly forces,

- his claim that James, the brother of the Lord, was not a relative of Jesus but just a generic Christian within the Jerusalem community,

- his assertion that the Gospels represent Homeric myths,

- and his employment of the Rank-Raglan heroic archetype as a means of comparison.

(Gullotta, p. 325. my formatting/numbering for quick reference)

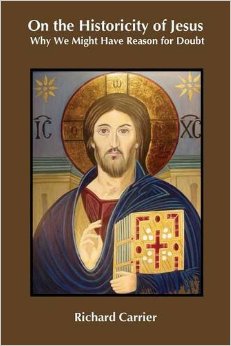

We move on to the sixth and final focus of Daniel Gullotta’s critical review of Richard Carrier’s On the Historicity of Jesus:

his employment of the Rank-Raglan heroic archetype as a means of comparison.

Let’s begin with Gullotta’s own explanation of what this term means:

Developed originally by Otto Rank (1884–1939) and later adapted by Lord Raglan (FitzRoy Somerset, 1885–1964), the Rank-Raglan hero-type is a set of criteria used for classifying a certain type of hero. Expanding upon Rank’s original list of twelve, Raglan offered twenty-two events that constitute the archetypical ‘heroic life’ as follows:

1. Hero’s mother is a royal virgin;

2. His father is a king, and

3. Often a near relative of his mother, but

4. The circumstances of his conception are unusual, and

5. He is also reputed to be the son of a god.

6. At birth an attempt is made, usually by his father or his maternal grandfather to kill him, but

7. he is spirited away, and

8. Reared by foster-parents in a far country.

9. We are told nothing of his childhood, but

10. On reaching manhood he returns or goes to his future Kingdom.

11. After a victory over the king and/or a giant, dragon, or wild beast,

12. He marries a princess, often the daughter of his predecessor and

13. And becomes king.

14. For a time he reigns uneventfully and

15. Prescribes laws, but

16. Later he loses favor with the gods and/or his subjects, and

17. Is driven from the throne and city, after which

18. He meets with a mysterious death,

19. Often at the top of a hill,

20. His children, if any do not succeed him.

21. His body is not buried, but nevertheless

22. He has one or more holy sepulchres.

While Raglan himself never applied the formula to Jesus, most likely out of fear or embarrassment at the results, later folklorists have argued that Jesus’ life, as presented in the canonical gospels, does conform to Raglan’s hero-pattern. According to mythicist biblical scholar, Robert M. Price, ‘every detail of the [Jesus] story fits the mythic hero archetype, with nothing left over …’ and ‘it is arbitrary that there must have been a historical figure lying in the back of the myth’.

(Gullotta, pp. 340f)

Let’s get some clarification and correction here. Otto Rank was on the lookout for Freudian meaning behind the myths and hence identified elements limited to the lifespan between the hero’s birth and his arrival at adulthood. Lord Raglan never read Rank and had no Freudian interest at all in relation to interpretations and analyses of myths. Contrary to Gullotta’s assertion Raglan did not “adapt” Rank’s “list”. Raglan developed his own list of 22 items, some of which by chance overlapped concepts on Rank’s earlier list.

Clearly, parts one to thirteen correspond roughly to Rank’s entire scheme, though Raglan himself never read Rank.65 Six of Raglan’s cases duplicate Rank’s, and the anti-Freudian Raglan nevertheless also takes the case of Oedipus as his standard.66

65. Raglan, “Notes and Queries,” Journal of American Folklore 70 (October-December 1957): 359. Elsewhere Raglan ironically scorns what he assumes to be “the Freudian explanation” as “to say the least inadequate, since it only takes into account two incidents out of at least [Raglan’s] twenty-two and we find that the rest of the story is the same whether the hero marries his mother, his sister or his first cousin” (“The Hero of Tradition,” 230—not included in The Hero). Raglan disdains psychological analyses of all stripes . . . .

66. For Raglan’s own ritualist analysis of the Oedipus myth, see his Jocasta’s Crime (London: Methuen, 1933), esp. chap. 26.

(Segal, p. xxiv, xxxix, xl)

Folklorist Alan Dundes set out Rank’s outline into a list format in order to compare it with Lord Raglan’s list of 22 points. Notice the way the Rank’s words have been changed for the sake of easier comparison. There is nothing wrong with that in context, but Daniel Gullotta is wrong to use Dundes’ reworded summary in place of Rank’s own outline when he is criticizing Richard Carrier for modifying some of the wording in Lord Raglan’s list.

| Rank (1909) |

Raglan (1934) |

| 1. child of distinguished parents |

1. mother is a royal virgin |

| 2. father is king |

2. father is a king |

| 3. difficulty in conception |

3. father related to mother |

| 4. prophecy warning against birth (e.g. parricide) |

4. unusual conception |

| 5. hero surrendered to the water in a box |

5. hero reputed to be son of god |

| 6. saved by animals or lowly people |

6. attempt (usually by father) to kill hero |

| 7. suckled by female animal or humble woman |

7. hero spirited away |

| 8. — |

8. reared by foster parents in a far country |

| 9. hero grows up |

9. no details of childhood |

| 10. hero finds distinguished parents |

10. goes to future kingdom |

| 11. hero takes revenge on his father |

11. is victor over king, giant dragon or wild beast |

| 12. acknowledged by people |

12. marries a princess (often daughter of predecessor) |

| 13. achieves rank and honours |

13. becomes king |

| 14. — |

14. for a time he reigns uneventfully |

| — |

15. – 22. etc …… |

Here is Rank’s outline of the hero myth, but note that I have converted Rank’s paragraph into a list format:

The standard saga itself may be formulated according to the following outline:

- The hero is the child of most distinguished parents, usually the son of a king.

- His origin is preceded by difficulties, such as continence, or prolonged barrenness, or secret intercourse of the parents due to external prohibition or obstacles.

- During or before the pregnancy, there is a prophecy, in the form of a dream or oracle, cautioning against his birth, and usually threatening danger to the father (or his representative).

- As a rule, he is surrendered to the water, in a box.

- He is then saved by animals, or by lowly people (shepherds),

- and is suckled by a female animal or by an humble woman.

- After he has grown up, he finds his distinguished parents, in a highly versatile fashion.

- He takes his revenge on his father, on the one hand,

- and is acknowledged, on the other.

- Finally he achieves rank and honors

Gullotta rhetorically asks

Why does Carrier preference a hybrid Rank-Raglan’s scale of 22 patterns, over Rank’s original 12? Could it be because Rank’s original list includes the hero’s parents having ‘difficulty in conception’, the hero as an infant being ‘suckled by a female animal or humble woman’, to eventually grow up and take ‘revenge against his father’?

(Gullotta, p. 242)

Ever since I read Daniel Dennett’s warning against argument by rhetorical question….

I advise my philosophy students to develop hypersensitivity for rhetorical questions in philosophy. They paper over whatever cracks there are in the arguments. (Dennett’s Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, p. 178)

….I hear a warning alarm and I check things out.

Gullotta’s rhetorical question is rendered null when we see (as I have set out above) that Rank did not say “the hero’s parents [were] having ‘difficulty in conception'” at all. Rank said “the hero’s origin is preceded by difficulties such as” — and the difficulties facing a virgin fiancée and her betrothed in the Jesus’ story are well known.

Moreover, when I read more than the page with the table of numbered points and look into what Rank himself wrote about his outline of hero myths, I find that, contrary to Gullotta’s inference, Rank did indeed include Jesus as a hero who fit his model!

Rank cites for the example of Jesus the prophetic announcements, the virginal mother and miraculous conception, the attempt on his life, his being whisked away to safety. Rank singles out the following details from Luke and Matthew as the key motifs to support his placement of Jesus in the same category as Sargon, Moses, Oedipus, Cyrus (yes, he was clearly historical!), Romulus, Hercules, Zoroaster, Buddha:

- angel sent . . . to a virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David

- thou shall conceive in thy womb, and bring forth a son, and shall call his name JESUS. He shall be great and shall be called the Son of the Highest

- seeing I know not a man?

- shall be called the Son of God.

- she was found with child of the Holy Ghost.

- the angel of the Lord appeared unto him in a dream

- And knew her not till she had brought forth her firstborn son

- she brought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger

- wise men from the east

- Where is he that is born King of the Jews?

- Herod the king

- the angel of the Lord appeareth to Joseph in a dream, saying, Arise, and take the young child and his mother, and flee into Egypt

- slew all the children that were in Bethlehem, and in all the coasts thereof, from two years old and under

- for they are dead which sought the young child’s life.

So if, as Gullotta rightly pointed out, Lord Raglan held back from detailing the stories of Jesus against his “typical mythical elements” his predecessor, Otto Rank, did not — as we read in detail on pages 39 to 43 of The Myth of the Birth of the Hero.

Those terms Gullotta quotes (“difficulty in conception”) are not taken from his reading of Otto Rank but from another scholar, Alan Dundes, attempting to summarize and compare Rank’s views in a simplistic list. A more accurate summary would allow for the births of the following figures being allocated to the same class as Jesus — as Otto Rank does indeed allocate them.

- Sargon

- Moses

- Karna

- Oedipus

- Paris

- Telephus

- Perseus

- Gilgamesh

- Cyrus

- Tristan

- Romulus

- Hercules

- Zoroaster

- Buddha

- Siegfried

- Lohengrin

Unusual and otherwise miraculous births or conceptions and dire situations threatening the survival of the child would cover it. But one would need to read more of the book than the single page authored by a third party with a graphic layout of simplified tables to know that.

Gullotta’s criticism that Carrier was avoiding Rank’s list because it did not support the mythical interpretation of Jesus so far fails on three grounds: Continue reading “Rank-Raglan hero types and Gullotta’s criticism of Carrier’s use of them”

Like this:

Like Loading...