Continuing and concluding…..

Peter Kirby cites an argument for interpolation not from a source agreeing with the argument but rather from a source disposing of it. He quotes Robert Webb:

A second argument is that the nouns used for ‘baptism’ in this text (βαπτισμός and βάπτισις, Ant. 18.117) are not found elsewhere in the Josephan corpus, which may suggest that this vocabulary is foreign to Josephus and is evidence of interpolation. However, we may object that using a word only once does not mean it is foreign to an author. Josephus uses many words only once . . . .

(Webb, p. 39)

I try to make a habit of always checking footnotes and other citations to try to get my own perspective on the sources a book is referencing. If one turns to a scholar who is agreeing with the argument that Webb is addressing, one sees that Webb has presented the argument in a somewhat eviscerated form. Here is how it is presented by a scholar who is trying to persuade readers to accept it as distinct from Webb’s format that is aiming to persuade you to disagree with it.

Against this, it seems that scholars try to blur the fact that this brief passage also contains unique words unparalleled in any of Josephus’s writings, notably words that, as I shall attempt to prove, are semantically and conceptually suspect of a Christian hand — βαπτιστής, βαπτισμός, βάπτισιν, έπασκουσιν, αποδεκτός.

(Nir, p. 36)

I covered the bapt- words in the previous post so this time I look at the other two, έπασκουσιν (as in “lead righteous lives”) and αποδεκτός (as in “if the baptism was to be acceptable“) along with some others. Keep in mind that what follows is sourced from Rivka Nir’s more detailed discussion in her book The First Christian Believer, and all the additional authors I quote I do so because Nir has cited at least some part of them. (To place Rivka Nir in context see my previous post.)

έπασκουσιν (ep-askousin = labour/toil at, cultivate/practise): άρετήν ἐπασκουσιν = lead/practise righteousness/virtue

The word appears in this section of the John the Baptist passage:

For Herod had put him to death, though he was a good man and had exhorted the Jews who lead [επασκουσιν] righteous lives and practise

justice towards their fellows and piety toward God to join in baptism . . .

There are two possible interpretations here. Should we translate the passage to indicate

- John was exhorting Jews to practice, labour at, lead virtuous and righteous lives and so undergo baptism?

Or

- should the scene be translated to indicate that John is commanding those Jews who were known for their righteousness and special virtue to be baptized (for the consecration of their bodies, since they had already become righteous through their living prior to baptism)?

Scholarly opinions are divided. Rivka Nir takes the side of those who interpret it in the latter manner: John is addressing a sectarian group who “practise” a righteous way of living and telling them to be baptized. What is in Nir’s mind, of course, is that the author of this passage was from such a sectarian community.

That we are dealing with an elect group is equally evident in how the passage depicts John’s addressees, whom the author designates as ‘Jews who lead righteous lives and practice justice towards their fellows and piety towards God’. This description lends itself to two readings. Most read the two participles forms έπασκουσιν [lead, practise, labour at] and χρωμένοις as circumstantial attributives modifying the exhortation itself.

Nir, p. 49

It can be interpreted to mean EITHER that John is exhorting Jews to lead righteous lives OR that John is exhorting Jews who lead righteous lives to undergo baptism. In this case the Jews spoken of are initiated into a community…. (See below for the grammatical details of these two possible interpretations.)

A cult defined by righteousness

If we follow the second reading, that the passage is depicting a call for a sectarian group that is identified as “labouring at, practising” righteousness to undergo and “join in” baptism. But if that is the case, what is so distinctive about “righteousness” in this context? Here again scholarly analysis has opened up insights the lay readers like me might easily miss. Righteousness in this context is not a common morality or keeping the rules of the Pharisees or Temple authorities. It is even used in the New Testament to distinguish between the Christian “righteous” sect and the “superficially/hypocritically righteous” Pharisees, scribes and Sadducees. The same is found in the Qumran scrolls. “Righteousness” can denote a sectarian identity. Nir, pp. 50f:

John Kampen examined the term ‘righteousness’ in the Qumran scrolls. He reached the conclusion that unlike its usage in tannaitic sources to denote charity and mercy, at Qumran it denoted sectarian identity and belonging to an elect group having exclusive claim to a righteous way of life. Matthew applies this term in the same sense, in connection to John’s baptism (3.15; 21.32). as well as in the Sermon on the Mount (5.10-11), where the author urges a sectarian way of life distinguished by righteousness. In other words, righteousness marked the sectarian identity of the group and served to preserve its boundaries.56 In this passage, as with Matthew and the Qumranites, ‘righteousness’ defines the lifestyle of this elect sectarian group as well as the boundaries separating it from society at large.

56. J. Kampen. “‘Righteousness’ in Matthew and the Legal Texts from Qumran’, in Legal Texts and Legal Issues: Proceedings of the Second Meeting of the International Organization for Qumran Studies. Cambridge 1995. Published in Honour of Joseph Μ. Baumgarten (ed. Μ. Bernstein, F. Garcia Martinez and J. Kampen; Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1997). pp. 461-87 (479, 481, 484, 486); Wink, John the Baptist in the Gospel Tradition, p. 36: ‘The word δικαιοσύνη does not spill out by accident; it is Matthew’s peculiar way of designating the faith and life of Christians and of Christianity in general (cf. Mt. 5.6. 10; 6.1-4). Meier (A Marginal Jew, II. p. 61) points out the resemblance between John’s description in Josephus and in Lk. 3.10-14. which portrays him as exhorting to acts of social justice. This may be accountable to two Greek-Roman writers, Josephus and Luke, who independently of each other sought to describe an odd Jewish prophet according to the cultural models known in the Greek-Roman world. Similarly, Ernst, Johannes der Täufer, p. 257.

Those footnoted references are not the easiest for lay readers to locate but I have copied extracts from a couple of them. See below for the full passages being cited in footnote 56.

The passage does not simply say that John’s followers were obeying the Jewish traditions, but that they were “practising” a righteousness that set them apart from others and that qualified them to enter the cultic community through baptism, a baptism that would, because they were practicing this righteousness, also ritually sanctify their bodies.

A further pointer to the passage being written from the perspective of a distinctive cult practice, a cult that Nir finds signs of in Qumran, the Fourth Sibylline Oracle and various (anti-Pauline) Jewish-Christian sects, is the language used to express the disciples “coming together”, “joining” in baptism.

βαπτισμω συνιεναι : join in baptism

For Herod had put him to death, though he was a good man and had exhorted the Jews who lead [επασκουσιν] righteous lives and practice [χρωμένοις] justice towards their fellows and piety toward God to join in baptism [βαπτισμω συνιεναι]. . . . When others too joined the crowds about him, because they were aroused [ήρθησαν] to the highest degree by his sermons, Herod became alarmed.

What commentators have discerned here is that the “joining” in baptism means entering into membership of a sectarian group, indicated by the inference that the call is for all of those who practise righteousness to gather together in a (collective) baptism. See details below.

Others, too, joined : Who were the others?

According to Meier in A Marginal Jew, II, pp. 58f

At first glance, the previous concentration of the passage on “the Jews” as the audience of John’s preaching might conjure up the idea that the unspecified “others” are Gentiles. There is no support for such an idea in the Four Gospels, but such a double audience would parallel what Josephus (quite mistakenly) says about Jesus’ audience in Ant. 18.3.3 §63 (kai pollous men Ioudaious, pollous de kai tou Hellenikou epegageto). However, if we are correct that epaskousin [ἐπασκουσιν] and chromenois [χρωμένοις] in §117 express conditions qualifying tois Ioudaiois, there is no need to go outside the immediate context to understand who “the others” at the beginning of §118 are.

So Meier concludes that the “others” were from the general Jewish population coming to see the righteous community respond to John’s call for baptism, but there is also a possibility that “others” might also refer to Gentiles, as in the Testimonium Flavianum (Ant. 18.63): ‘He [sc. Jesus] won over many Jews and many Greeks’, as well as Christians: Mt. 27.42: Lk. 7.19: Jn 4.37: 10.16: 1 Cor. 3.10: 9.27.

For O. Cullmann (‘The Significance of the Qumran Texts for Research into the Beginnings of Christianity‘. JBL 74 (1955). pp. 213-26 (220-21), such Hellenistic Christians formed the earliest nucleus of Christian missionaries who carried the gospel to Samaria and other non-Jewish areas in the Land of Israel.

Nir, p. 50

For baptism to be αποδεκτός (acceptable) . . .

In this passage, John says that ‘if baptism was to be acceptable [αποδεκτήν αύτώ]’ to God.60 ‘they must not employ it to gain pardon for whatever sins they committed, but as a consecration of the body’.

What kind of baptism might ‘be acceptable’ to God?

In biblical usage, this expression relates to the sacrificial system at the temple to designate an offering accepted by God.61 In the New Testament, the compound adjective αποδεκτός, meaning ‘acceptable’, occurs in connection with sacrifices only in 1 Peter: ‘spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God’ (2.3-5). . . .

The author of this passage speaks of John’s baptism in terms paralleling the atonement sacrifices in the temple, by means of which individuals ask God’s acceptance of their offering that their sins may be forgiven. Joseph Thomas64 focused on one of the features of Baptist sects (Ebionites, Nazarenes, Elcasaites) that withdrew from the traditional temple and sacrificial worship and conceived of baptism as a substitute for sacrifices. To his mind, cessation of sacrifices and the baptismal rite are interrelated: instead of sacrifices in atonement for sins, it is holy baptism that atones for sins.65 The notion of baptism as replacement for the Jewish sacrificial system is distinctly Christian: Jesus is the expiatory sacrifice in place of the temple sacrifices and his death atones for all the sins of the world.66 By baptism, the baptized identify with Jesus’ atoning sacrifice, becoming a sacrifice themselves, and their sins are forgiven, as expounded in Rom. 6.2-6.

61. Webb, John the Baptizer and Prophet, pp. 166, 203.

64. Thomas. Le mouvement Baptiste, pp. 280-81: J.A.T. Robinson, ‘The Baptism of John and the Qumran Community’, HTR 50 (1957). pp. 175-91 (180).

65. Thomas. Le mouvement Baptiste, pp. 55-56: Webb, John the Baptizer and Prophet, p. 120. On baptism in place of sacrificing al Qumran, see subsequently.

66. Eph. 5.2: Rom. 12.1.

Nir, pp. 51f

In the account in Josephus we read that for John’s baptism to be “acceptable” (αποδεκτος) it must not be used to grant forgiveness of sins but for the consecration or sanctification of the body, a function of erstwhile temple sacrifices.

Baptism, a central rite

John’s baptism was being preached and proclaimed, a point in common between Josephus and the Gospels. The Gospel of Matthew underscores the central importance of baptism when he has Jesus command his disciples to go into the world and baptize new disciples.

Moreover, other scholars have wondered why Josephus did not explain the term “baptism” here.

What would Greek and Roman readers unfamiliar with Christian sources understand by this term? They were familiar with the verb βάπτω, which means ‘to dip/be dipped’ or ‘to immerse/be submerged’, and with the verb βαπτίζω, which in classical sources denotes ‘to immerse/be submerged under water’.49 How would they understand a designation referring to someone who immerses others with this particular immersion? How could Josephus use this designation without defining it?50

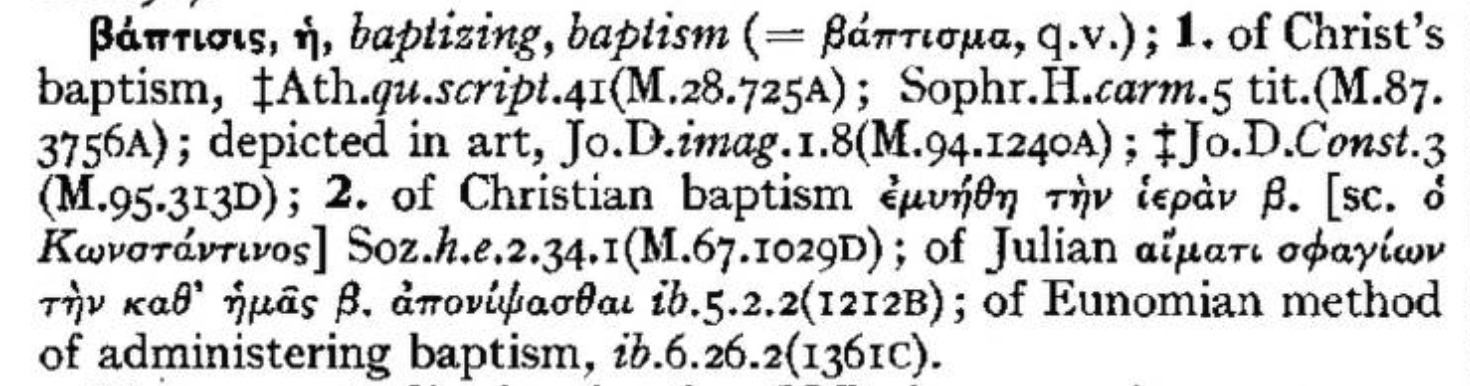

Moreover, this passage uses two terms for John’s immersion: βαππσμός and βάπτισις. which Christian tradition applied as distinctive of Christian baptism. And it is only here that they occur in Josephus, diverging markedly from the terminology he applies to the Jewish ritual immersion for purification from external physical defilement.51

49. Metaphorically: soaked in wine. See Oepke. ‘βάπτω’, TDNT, I. p. 535.

50. This bewilderment was already raised by Graelz (Geschichte der Juden. III. p. 276 n. 3): and Abrahams (Studies in Pharisaism, p. 33) noted that this designation might be an interpolation. Mason (Josephus and the New Testament, p. 228) attempts to distinguish between ‘Christ’ and ‘called the Christ’, as in the latter case Josephus would not need to explain the title, and this applies to John, ‘called the Baptist’. Some argue (e.g. Webb, John the Baptizer and Prophet, pp. 34, 168) that John’s being called by this name in the Gospels and in Josephus proves it became distinctive of John and the permanent Greek designation, hence its usage by the evangelists as well as Josephus. Indeed, John is called ‘the Baptist’ in the Synoptics, but this epithet is not attached to his name in Acts and in the Fourth Gospel.

51 To describe Jewish immersions, Josephus usually uses the verb λούεσθαι or άπολούεσθαι, as he does for the Essenes and Bannus; see K.H. Rengstorf, A Complete Concordance to Flavius Josephus (Leiden: EJ. Brill. 2002). I. p. 290. But βάπτισις is a term Christian sources apply to the baptism of Christ or Christian baptism; see Athanasius Alexandrinus, Quaestiones in scripturas 41 (M.28.725A); LPGL, p. 284. Origen uses βαπτισμός for John’s baptism, but in many sources this term applies to Christian baptism in general: see Heb 6.2: βαπτισμών διδαχής; Col 2.12: ‘you were buried with him in baptism (έν τω βαπτισμώ), you were also raised with him’; Chrysostom, Hom. in Heb. 9.2 ( 12.95B). This term also applies to the repeated baptismal rites of heretical sects, e.g., Ebionites, Marcionites, etc. See LPGL, p. 288. On the possibility that John’s baptism in Josephus was also a repeated ritual, see subsequently.

Nir, p. 48

It is through discussions of such technical points that Nir argues for a Jewish-Christian provenance of the John the Baptist passage in Antiquities of the Jews. When criticisms against the interpolation view point to comparisons with specific New Testament terminology they are missing a key facet of the argument: the interpolation is said to be consistent with certain Jewish Christian practices and thus contrary to the Christian ideas represented by the New Testament.

I still have some questions about Rivka Nir’s presentation but I have tried to set it out in these posts as fully (yet succinctly) as I reasonably can. The less background knowledge we have the easier it is to be persuaded by new readings. The more we learn about the Jewish and Christian worlds in their first and second century contexts the more aware we become of just how little we really know and how vast are the gaps in our knowledge. There is little room for dogmatism, for certainty, for “belief”, in a field of inquiry where even the sources themselves are not always what they seem. That’s true of much ancient history and it is especially true of the history of Christian origins.

So where does John the Baptist fit in history?

Our most abundant historical sources are Christian. In the canonical gospels John the Baptist is the prophetic voice announcing the advent of Jesus. He is depicted variously as a second Elijah, an Isaianic voice in the wilderness, and as the son of a temple priest. Always he represents the Jewish Scriptures prophesying their fulfilment in Jesus Christ. As such, he functions as a theological personification.

If John’s literary function is to personify a theological message we might think that he could still be more than a literary figure. Could he not also have had a historical reality? Yes, of course he could. But a general rule of thumb is to opt for the simplest explanation. If we have a literary explanation for the presence of John the Baptist that explains all that we read about him in the gospels, then there is no need to seek additional explanations. If there is independent evidence for John in history then we are in quite different territory.

The earliest non-Christian source we have is found in Antiquities 18.116/18.5.2 (by Josephus). If this passage was indeed penned by Josephus or one of his scribal assistants then it would be strong evidence — strong because it is independent of the gospels and in a work of “generally reliable” historical narration — that there was a John the Baptist figure in history, however that figure might be interpreted.

The passage would not confirm the gospels’ theological role of John. After all, in Josephus the JtB passage is set some years after the time of Jesus and Jesus is never mentioned in relation to John.

In the eyes of some scholars, those stark differences from the gospels stamp the passage with authenticity. This would mean that Christian authors took John from history and reset him in time to make him a precursor of Jesus. If this is how John entered the gospels then the common notion among scholars of Christian origins and the historical Jesus have no grounds on which to reconstruct a historical scenario in which Jesus joined the Baptist sect only to break away from it. John would then remain as nothing more than a theological personification of the OT pointing to fulfilment in Christ.

But if there are reasonable grounds for suspecting that the passage in Josephus is from a Jewish-Christian hand, then we are left without any secure foundation for any place of such a figure in history. Another proposal is that the passage is genuinely Josephan but removed from its original context where it spoke of another “John” from the one we associate with Christian tradition. What is certain is that the passage raises questions. It is susceptible to debate. It can never be a bed-rock datum that establishes with certainty any semblance of a John the Baptist figure comparable to the one we read about in the gospels.

.

Detailed explanations of linked points above……

Continue reading “Where does John the Baptist fit in History? — The Evidence of Josephus, Pt 7”

p. 288

p. 288