Many of us are aware of the arguments of Frank Zindler that the John the Baptist passage in Josephus is an interpolation, but we leave those aside here and look at what Rivka Nir of the Open University of Israel offers as reasons for doubting the genuineness of the John the Baptist passage in Antiquities. The following is drawn from “Josephus’ Account of John the Baptist: A Christian Interpolation?” by Rivka Nir in the Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus (2012) 32-62.

Many of us are aware of the arguments of Frank Zindler that the John the Baptist passage in Josephus is an interpolation, but we leave those aside here and look at what Rivka Nir of the Open University of Israel offers as reasons for doubting the genuineness of the John the Baptist passage in Antiquities. The following is drawn from “Josephus’ Account of John the Baptist: A Christian Interpolation?” by Rivka Nir in the Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus (2012) 32-62.

Rivka Nir’s article also suggests her own answer to the old question of the origins of the idea of baptism as we read it in connection with John the Baptist.

To begin, let’s refresh our memory of what we read about John the Baptist in Josephus. The translation following is as it appears in Rivka Nir’s article:

(116) But to some of the Jews the destruction of Herod’s army seemed to be divine vengeance, and certainly a just vengeance, for his treatment of John, surnamed the Baptist.

(117) For Herod had put him to death, though he was a good man and had exhorted the Jews who lead [ἐπασκοῦσιν] righteous lives and practice [χρωμένοις] justice [δικαιοσύνῃ] towards their fellows and piety [εὐσεβείᾳ] toward God to join in baptism [be united by baptism] [βαπτισμῷ συνιέναι].

In his view this was a necessary preliminary if baptism [βάπτισιν] was to be acceptable to God. They must not employ it to gain pardon for whatever sins they committed, but as a consecration of the body implying [or: on condition] that the soul was already thoroughly cleansed by [righteousness—R.N.] [δικαιοσύνῃ].

(118) When others too joined the crowds about him, because they were aroused [ἤρθησαν] to the highest degree by his sermons, Herod became alarmed. Eloquence that had so great an effect on mankind might lead to some form of sedition, for it looked as if they would be guided by John in everything that they did. Herod decided therefore that it would be much better to strike first and be rid of him before his work led to an uprising, than to wait for an upheaval, get involved in a difficult situation, and see his mistake. (Antiquities 18.5.2 116-119)

Rivka Nir first gives us the three pillars upon which the authenticity of this passage rests (I omit supporting details in the footnotes and add bold format):

- In view of dissimilarities or even contradictions between the Gospel and Josephus versions about John the Baptist, it is reasoned that had the passage been interpolated by a Christian, the interpolator would most likely have accommodated the account to its version in the Gospels.

- The passage’s correspondence in vocabulary and style to Josephus’ Antiquities in general and books XVII–XIX in particular.

- The presence of the text in all the Josephus manuscripts and its mention by Origen in his Against Celsus (1.47), dated to 248 CE.

Early suspicions of a brazen forgery

1893: Herman Graetz called the passage “a brazen forgery”.(Geschichte der Juden, III, p. 276, n. 3)

Others who have argued similarly:

- 1902: S. Krauss, Das Leven Jesu nach jüdischen Quellen, p. 257

- 1964 4th ed from 1886: E. Schürer, Geschichte des Jüdischen Volkes im Zeitalter Jesu Christi, I, p. 438, n. 24

- 1935, first pub. 1919: G. Dalman, Sacred Sites and Ways: Studies in the Topography of the Gospels, p. 98

- 1987, J. Efron, Studies on the Hasmonean Period, p. 334, no. 218 — also claims the paragraph on James, the brother of Jesus, is likewise a Christian interpolation, pp. 334-336.

Interrupts the flow

Among those who have argued that the passage interrupts the flow of the surrounding text and could easily be removed:

- 1970: L. Herrmann, Chrestos, Témoignages paients et juifs sur le christianisme du premier siècle, p. 99

Supportive tone towards John

Among those who have puzzled over the passage’s “positive and supportive tone towards John which is inconsistent with Josephus, the fierce opponent of anyone seeking to challenge the legitimate government or promote rebellion of any sort”:

- 1964 4th ed from 1886: E. Schürer, Geschichte des Jüdischen Volkes im Zeitalter Jesu Christi, I, p. 438, n. 24

- 1973: E. Schürer, The History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus Christ (175 BC–AD 135), I, p. 346

- 1928: M. Goguel, Au seuil l’évangile Jean Baptiste, p. 19

- 1994: Meier, A Marginal Jew, II, p. 99

Unexplained use of a Christian epithet

“The Baptist” as an epithet of John was distinctive among Christian sources. It appears as a name in first-century CE Greek only in the synoptic Gospels. The usual reply to this question is that “John the Baptist” was how he was known generally and to all from his own time. But if so, we have the problem that he is not known by that name in either the Acts of the Apostles nor in the Gospel of John.

Why did Josephus use this term, especially addressing Greek and Roman audiences, and leave it unexplained? These questions have cast doubt on the authenticity of the passage among:

- 1893: Herman Graetz, Geschichte der Juden, p. 276, n. 3

- 1902: Samuel Krauss, Das Leben Jesu nach jüdischen Quellen, p. 257

- 1973 (first German ed 1886): Emil Schürer, A History Of The Jewish People In The Time Of Jesus Christ, p. 346, n. 24

- 1912: Alban Blakiston,John Baptist And His Relation To Jesus, p. 71

- 1926: Joseph Klausner, Jesus of Nazareth: His Life, Times, and Teaching, p. 265 (considers the passage authentic apart from a few isolated words)

- 1931: Robert Eisler, The Messiah Jesus and John the Baptist According to Flavius Josephus, pp. 245-52

- 1970: Léon Herrmann, Chrestos: Témoignages Païens Et Juifs Sur Le Christianisme Du Premier Siècle, pp. 99-100

- 2000: Jonathan Klawans, Impurity and Sin in Ancient Judaism, p. 138 discusses Josephus’s reference with caution (“even if Josephus’s account of John is authentic…”)

Uncharacteristic and isolated use of the epithet

[F]urther incredulity is raised by the presence of βαπτισμός and βάπτισις, the two terms used in the passage for the immersion associated with John. Being quintessentially Christian terms that Christian tradition applied to Christian baptism, they occur in Josephus only within this passage, marking divergence from his usual usage of terms associated with the Jewish ritual of immersion—λούεσθαι, ἀπολούεσθαι, meaning to purify a person from external physical defilement.

A New Reason to Question the Authenticity of the Passage

We now come to Rivka Nir’s new argument casting doubt upon the originality of the John the Baptist passage in Josephus.

Of particular importance to uncovering the theological identity of this baptism is its description as an external physical purification, whose efficacy is preconditioned by inner spiritual purification. I intend to show that baptism of this nature did not exist amid mainstream Jewish circles of the Second Temple period. Such baptism appeared and developed within sectarian groups on the margins of Judaism, as at Qumran. It was then carried on and practised by Jewish-Christian groups over the first centuries CE. . . .

John’s outspoken dismissal of baptism ‘to gain pardon from whatever sins’, before commending his own version, suggests, as I intend to prove, an underlying polemic against Christian orthodox baptism.

Following are Rivka Nir’s arguments to support this claim:

1. Early-Christian or Jewish-Christian Characteristics of John’s Baptism

John’s baptism as it appears in Josephus is actually characteristic of an “early-Christian or Jewish-Christian sectarian” ritual.

Like early Christian/Jewish-Christian baptism ceremonies, it is a collective mass baptism

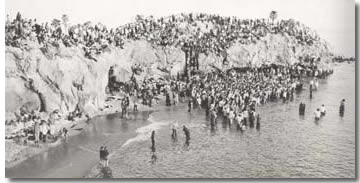

Note that John is said to have called on the people “to be united by” or “to join in” baptism, and that the masses heeded his call. Add to this the image of the masses heeding his call and we have the strong suggestion of a “collective mass baptism” of many being initiated into a select group under the direction of a leader.

Like early Christian/Jewish-Christian baptism ceremonies, it is a consecration of the body for those whose souls are already purified

The Greek verb σύνειμι (βαπτισμῷ συνιέναι) means to come together, to assemble for a common purpose. Webb translates the dative βαπτισμῷ in an instrumental sense—‘by means of baptism’.

Moreover, John appears to be addressing a crowd who are already practising a way of life that sets them apart from ordinary Jews. John is addressing those who are distinct from others because they lead righteous lives, practice justice towards others and piety towards God. The words “lead” and “practice” are usually taken to refer to the exhortation by John, but they can instead be read as qualifying “the Jews” to whom he was speaking. In support of the latter interpretation are two points:

- the reference to “others” who came to hear John and were persuaded to join the first group;

- the meaning of baptism as a purification of the body for those who, prior to baptism and as a condition for baptism, had purified their souls.

The description of a sectarian group as practicing righteousness is not as vague as it may sound to us today. The Damascus Document in Qumran identifies the sectarians it addresses as those who “know righteousness”. Righteousness is a term used to identify the sectarian community. Similarly, in 1 Enoch and again in the Gospel of Matthew “those who practice righteousness” is used to describe the sectarian community and to distinguish them from outsiders.

Such a baptism as an initiation rite was known among early Christian and (as we know from the Pseudo-Clementines) Jewish-Christian circles. Noteworthy also is that baptism among these early Christian and Jewish-Christian sectarians was a collective, group act, that became the central mark of formal identification with the community.

Rivka Nir justifies her use of the Pseudo-Clementines:

There is common agreement that these writings, usually dated to the fourth century but integrating ample material from earlier sources, reflect the world of ideas and beliefs within Jewish-Christian circles of the fijirst centuries CE. On the basis of this parallel and affinities with other early Christian writings, it would be safe to assume that the author or redactor of the Josephus passage was close to these early Christians or Jewish-Christian groups. Such authorial proximity to Jewish-Christian circles of the Pseudo-Clementine writings may well account for the polemical tenor of our passage.

Like early Christian/Jewish-Christian baptism ceremonies, it is a substitute for the sacrificial temple cult

In the Josephus passage we read that John’s baptism was something that was to be “acceptable to God”. Nir observes that this is an expression that is applied to temple sacrifices (cf Lev. 1:3; 19:5; 22:19-29; Jer. 6:20; Isa. 56:7), and that in 1 Peter 2:3-5 the same phrase is used in connection with such sacrifices.

So in Josephus we read that the baptism of John is explained in terms that parallel those used of expiation sacrifices in the temple cult. One bringing a sacrifice to the Temple would ask God to accept it so that his sins could be forgiven.

The notion that baptism was a substitute for the Jewish sacrificial cult is manifestly Christian: Jesus is the expiatory sacrifice in place of the temple sacrifices and his death atones for all the sins of the world. One who undergoes baptism thereby identifies with Jesus’ atoning sacrifice, becoming a sacrifice himself, and all his sins are forgiven (Rom. 6.2-6). But this idea was equally picked up by Jewish-Christian sects, notably the Ebionites and Elkasaites. Forsaking the traditional sacrificial cult in the temple, they practised immersion in its place—holy baptism replaced temple sacrifices as a means of expiating sins. (p. 44 my emphasis)

2. John’s Baptism and Jewish Immersions in the Second Temple Period

John’s Baptism and Mainstream (Non-Sectarian) Jewish Immersions

On the basis of what we learn from Josephus, Philo and the tannaitic literature, the “central circles of Second Temple Jewish society” practised immersions according to the laws of impurity and purification as set out in the Hebrew Bible, in particular Leviticus 11-19 and Numbers 19.

These ritual immersions cleansed the body of a variety of states of impurity:

- contact with a corpse

- skin infections

- emissions of bodily fluids

There was no relationship with cleansing a soul from sin and no relationship to repentance. Repentance and forgiveness were tied to the sacrificial cult of the temple.

Some scholars have attempted to find the source of John’s baptism among the Essenes and with Josephus’ own mentor, Bannus. But the immersions practiced by these were in complete accord with common Jewish immersions. They were performed as individual acts; they were performed regularly and repeatedly; they were also for the purpose of cleansing or ritually purifying the body from physical uncleanness or contact with ritually unclean persons. There was no call from a leader for a group to so “wash” themselves; there was no collective immersion; there was no association with spiritual repentance or ritual to join a group.

Others appeal to Philo as pointing to a precedent for John’s baptism. Philo drew analogies between physical and moral purity and yes, did say it was pointless for a person pure in body yet still impure in mind to offer prayers and sacrifices at the temple. At the same time, however, what he says had nothing to do with ritual immersions or of baptism as a precondition to a cult.

The baptism of John as explained in Josephus has no relationship to ritual ablutions as we find them in the early rabbinic literature and that are thought to have originated much earlier.

John’s Baptism and Sectarian Immersions in Judaism

Rivka Nir rejects suggestions that Judaism as a mainstream religion was so fragmented that there was not “even one commonly-shared indispensable characteristic”. Hence the Qumran community she regards as part of the world of fringe-Judaism.

Going against today’s ascendant view, my research embarks from the following premise: it assumes the existence of a distinct first-century CE Jewish society highly conscious of its religious, ideological and ritual uniqueness. All its component groups and movements, with the Pharisees at the fore, shared fundamental principles, beliefs and ideas which, despite differences, formed the common ground marking the boundary between Judaism and what lay outside it. Reflecting the inner world of this Judaism — its faith, hopes of redemption, cult and religious commandments which dictated its way of life — are the clear-cut quintessential Jewish sources at our disposal:

- the Hebrew Bible, which provided the religious, ritual and cultural basis for Judaism of the Second Temple period;

- the Apocrypha;

- Josephus,

- Philo

- and early layers of Talmudic literature.

Existing on the margins of this central Judaism were groups and sects, such as the Qumran sect and community which produced the apocalyptic works of the Pseudepigrapha. The affinities between these marginal groups and Christian theology indicate that our search for Christian origins and a nascent milieu should be conducted in their midst. (pp. 45-46, my formatting)

The Qumran community required members to convert or repent spiritually on the understanding that this was a prerequisite for bodily purification. The two were interdependent: ritual purification was meaningless without moral purification. Water could only remove physical uncleanness, so repentance was necessary first. It was this repentance that was the precondition for entering the cultic community, and this was to be followed by immersion.

Similarly, the fourth Sibylline Oracle instructs people to purify their bodies in living water after they have forsaken their sins.

Both the Qumran community and the Sibylline Oracles abandoned the temple cult and its sacrificial system and turned to repentance and immersion as the way to salvation. Several biblical passages connect water with washing away sins, but these are figurative and have nothing to do with ritual immersion and less to do with immersion that was preconditioned by repentance.

In tracing the development of such baptisms as ascribed to John and the Qumran sect . . . I consider it essential to underline their fundamental difference and departure from any possible similarities: nowhere in Judaism before Qumran, neither in biblical times nor in the Second Temple period, was the notion that one could be made clean in body only if one was pure in heart ever connected to the rite of immersion. (p. 56, my emphasis)

3. John’s Baptism and Baptism in Early Christianity and Jewish Christian Sects

One of our earliest Christian documents, dated to the last quarter of the first century CE, is the Book of Hebrews. In Heb. 10:22 we read:

Let us draw near with a true heart in full assurance of faith, having our hearts sprinkled from an evil conscience, and our bodies washed with pure water.

Like the baptism of John according to Josephus, this early Christian baptism links moral and bodily purity, making the former the condition for the latter. Christianity is generally thought to have eventually lost any association between baptism and physical purification as it distanced itself increasingly from Judaism’s regulations relating to purity and impurity. What we see in Hebrews, however,

are remnants of the historical link between Christian baptism and its antecedent Jewish practice of immersion for bodily purification.

Rivka Nir thinks that this association was not entirely discarded by Christianity:

Rather, in the early phases of Christianity, such immersions persisted side by side with Christian sacramental baptism.

Nir cites evidence for this insistence that inner purification is the precondition for physical immersion from the late fourth-century Apostolic Constitutions, comments by St. Cyrial of Jerusalem (Catechesis 3.4)), and the Pseudo-Clementine writings.

And when it remains that the catechumen is to be baptized, let him learn what concerns the renunciation of the devil, and the joining himself with Christ; for it is fit that he should first abstain from things contrary, and then be admitted to the mysteries. He must beforehand purify his heart from all wickedness of disposition, from all spot and wrinkle, and then partake of the holy things; for as the skilfullest husbandman does first purge his ground of the thorns which are grown up therein, and does then sow his wheat, so ought you also to take away all impiety from them, and then to sow the seeds of piety in them, and vouchsafe them baptism. (Cons. Apostolorum 7, sec. 3.40)

‘…purify your hearts from evil by heavenly reasoning, and wash your bodies in the bath. For purification according to the truth, is not that the purity of the body precedes purification after the heart, but that purity [of the body] follows goodness [of the heart]’ (Clem. Hom. 11.28)

Not how the latter passage in particular “is formulated in a manner exactly reminiscent of John’s immersion”.

As in the Josephus passage, the desirable form of baptism conveys two elements—immersion of the body and inner repentance. Both sources emphasize the sequence of events—a purified heart must precede bodily cleansing.

And both sources treat the matter somewhat polemically, distinguishing what is affirmed from what is rejected: ‘immersion is good not when … but only when…’ (That is, not when bodily cleansing precedes purity of the heart but only when cleansing [of the body] comes after goodness [of the heart]). (p. 58, my formatting and emphasis)

So Rivka Nir concludes on the basis of

- the Qumran scrolls

- the Fourth Sibylline Oracle

- the Pseudo-Clementine writings

- and the Apostolic Constitutions

that we may reasonably infer that John’s baptism as found in Josephus’ s Antiquities

had its origins in sectarian groups at the margins of Second Temple Judaism . . . and continued to exist within Judea-Christian groups during the first centuries CE. . . .

It was a form of immersion that maintained a firm tie to Jewish ritual immersion meant to purify the body, but already incorporated an aspect of the inner repentance characterizing Christian immersion. In Johannine baptism and the immersion practised within these sects,

- repentance precedes immersion;

- the former is what brings about forgiveness of sins,

- and the immersion is perceived as a substitute for the sacrificial cult at the Temple.

(p. 59, my formatting and emphasis)

It is even possible, according to Epiphanius and the Pseudo-Clementines, that sects that practiced this type of baptism did so as a daily ritual as well as a singular rite of initiation into the sect.

4. The Polemical Tone of John’s Baptism Account

Rivka Nir draws attention to the odd way the explanation of John’s baptism is introduced in Josephus. The first point that is made is what the baptism is NOT. The explanation begins:

‘…if baptism [βάπτισιν] was to be acceptable to God’, they must not employ it ‘to gain pardon for whatever sins they committed’.

This manner of introduction suggests that its author was engaged in a polemic. If so, against whom?

The author is refuting the idea that baptism itself is for the remission of sins. It is for the consecration of the body. The soul had already been purified prior to baptism. Baptism was NOT “for repentance” or for the forgiveness of sins.

It does appear that the author is in fact arguing against the sacramental orthodox Christian baptism.

That is, the Josephan account appears to “reflect an intra-Christian dispute concurrent with the formation of the Christian rite of baptism during the first centuries CE.” Did baptism itself bring about forgiveness or was purification a requirement that preceded baptism? Should Christian baptism be associated with bodily purification?

Whoever wrote the passage clearly understood the authoritative teaching was that moral righteousness had to precede baptism and that baptism was for bodily consecration — contrary to the orthodox Christian view.

Conclusion

Josephus, as is well known, remained a faithful Jew. He was neither initiated into one of the Jewish-Christian sects, nor did he convert to Christianity. Thus, the inevitable conclusion is that the description of John’s baptism, as provided in the passage under review, was not written by Josephus, but was rather interpolated or adapted by a Christian or Jewish-Christian hand.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

It’s certainly interesting, but how did a heretical interpolation make it into the copy of Antiquities in the Eusebius’s Caesaria library?

I accept Carrier’s argument that all our extant copies can be traced back to that one as the explanation for the interpolation of the Testimonium.

The passage had to have been entered very early. It was there in Origen’s copy. The baptism it speaks of was the understanding of the earliest Christians. The subsequent views that became the orthodoxy do not appear to have considered the earlier view some sort of outright “anathema” — the Book of Hebrews made it into the canon, after all. And the primitive view was attributed to a pre-Christian movement in Josephus, so I hardly see Eusebius or others being overly bothered by what this Jewish historian thought was happening.

By “very early” I think we could even allow the passage being added before the canonical gospels were widely known. But I find the evidence for their composition pointing more strongly to the second century than the first. The passage as located in Josephus is out of synch with the canonical narrative, after all.

The late Geza Vermes, former Professor Emeritus of Jewish Studies at Oxford, seemed to think the passage on John was reliably the authentic work of Josephus and typical of his style. Vermes comments “There is no reason to suspect here a Christian hand”. He also thought that the passage concerning James, the brother of Jesus was authentic (the least questionable of the three anecdotes) as was the core of the Testimonium. He summarised his views in an article in 2010 in Standpoint magazine and they seem reasonable views. The above article seems a trifle over-elaborate.

http://standpointmag.co.uk/node/2507/full

Jesus in the Eyes of Josephus

GEZA VERMES

VERMES (about Ant 20)

It lacks New Testament parallels that might have inspired a forger.

CARR

You would think Vermes would tell his readers that part of this passage in Josephus uses the same wording as Matthew 1:16

Why did Vermes hide this from his readers?

Even without the distinctive Matthew 1:16 detail, the initial argument is one of New Testament scholarship’s facile favorites. It is essentially another instance of the rhetorical “Why would anyone make it up?” We know too many NT scholars don’t like having their well-worn rhetorical questions actually thought through and answered. It’ not how they like to play the game.

“Why did Vermes hide this from his readers?”

Is it because he is part of the universal ongoing conspiracy against Jesus-Mythers?

Since you have returned here, would you like to respond to my request for supporting evidence for your/McGrath’s assertion that Rivka Nir’s argument is self-contradictory? Or is reasoned engagement with the arguments beyond you?

Labels like “parallelomania” and blanket statements like “self-contradictory” aren’t meant to engage in the debate, but rather to stifle it.

Agreed (sigh!). We have Google Earth to show what every place in the world is really like, but we have no way of knowing the psyches of those who fly by with fatuous comments and who never stay long enough to be called to account.

Nah, it’s probably because Vermese simply hadn’t researched it and didn’t know there was an almost direct lift from Matthew 1:16 in that bit of Josephus.

If he had known about it, his integrity would have prevented him writing what he did.

“…it is hard to address the points made in the article when they seem at times to be self-contradictory”

Indeed, that does appear to be the calling-card of mythicism.

Oh my goodness! Talk about obsession with “correct thoughts”! Rivka Nir is NOT a mythicist! Nor, I am sure, were Herman Graetz, S. Krauss, E. Schürer, G. Dalman, J. Effron. If you agree with McGrath’s assertion that the treatment is self-contradictory it would be helpful if you actually went one step further than he does and point out why or where specifically it is so. McGrath has a habit of making sweeping claims that he never supports.

Your previous point about Geza Vermes likewise misses the point. Just declaring an opposing view — a view that Rivka Nir herself acknowledges is the mainstream one – does nothing to address her own arguments. We all know the mainstream arguments. Repeating them is not a valid justification for refusing to revisit a question from a new point of view.

It seems that you want us all to submit to the authority of the conventional wisdom represented by one scholar rather than actually examine arguments on their own merits.

If we look John the Baptist as an Anti-Roman, A Jewish Patriot or a Terrorist against Romans, the Baptism is that you have been citizen under Pagan rule and paying taxes. John, did not live inside in wilderness and did not eat the produce of the Pagan ruled land.

Baptism is the ritual to join the army against Romans.

‘If we look John the Baptist as an Anti-Roman, A Jewish Patriot or a Terrorist against Romans’

Why would anyone take such an utterly ridiculous view?

I am not sure that the John passage is authentic, but I find myself disagreeing with the argument here. Firstly, Nir undermines her own new argument by admitting that such a usage of baptism was prevalent at Qumran. I don’t see any relevance in the fact that it was not mainstream, and if we do identify the Essenes with Qumran, then Josephus himself would have had some exposure to their practices. The existence of such Jewish sectarianism need not make us fixate on Christianity as the only possible point of comparison.

I also question the argument from the passage’s seemingly supportive tone. That John was a revolutionary is conjecture. I don’t know of any evidence that he was planning an insurrection, and whether or not he was, Josephus seems unsure and believes Herod apparently jumped the gun. Contrast this with other wannabe messiahs whom Josephus describes and did actually stage some sort of insubordinate display.

I think Nir’s point about Qumran is that the fact that it was not mainstream Judaism would lead us to expect Josephus to lack any respect for the practice. It is not the way of Josephus to write positively of fringe movements.

It does appear that the author is in fact arguing against the sacramental orthodox Christian baptism.

for me, the new argument of Rivka Nir is only the recognition of this implicit polemic against the Orthodox baptism, independently from being the John’s baptism pre-christian or judeo-christian.

In fact, the alternative to the interpolation thesis, is that it was Josephus himself the polemizer against the illegittimate Orthodox appropriation of (more kosher) John by Gospels, than pointing to make Josephus an indirect witness of proto-orthodox Christians in his time.

But the problem with this view is that the *orthodox* Epistle to Hebrews did practice *still* the ”judeo-christian” baptism: even if Josephus did know Orthodox christians, he couldn’t polemize with them (about the baptism) because these Orthodoxs were without the baptism against which ”Josephus” polemizes.

either the same Josephus did polemize – and then he knew the Gospels – against the Orthodox baptism….

…or the Judeo-christian forger did that polemic in his place.

Tertium non datur.

Giuseppe

It certainly seems possible for Josephus to have been familiar with some Hellenistic Christian ritual by ~90CE, or whenever AJ was written. What other sources do we have which advocate the “orthodox” baptism in which sins are actually forgiven by means of the physical right itself? Mark seems to say that the baptism is for the forgiveness of sins, although this may be seen as his not caring to point out the finer details. Matthew 3:7-8 may, in fact, describe John’s baptism in a way that is consistent with the passage in Josephus.

Unless, it was just a common misunderstanding of this type of baptism, as Nir argues that it was not known in mainstream Judaism. Why even defend it, then? John’s ministry would have been seen as a long time ago to Josephus, and never led to an insurrection. It’s possible he saw him in a similar fashion as Onias the Righteous/Honi the Circle Drawer, who also existed on the fringe but seemingly lacked political drive.

My understanding of Josephus’s treatment of Onias is that he was consistent with the righteous prophets who did defend the true doctrines of orthodoxy. He was righteous and God heard him, and he did not oppose the establishment or teach a new practice or even gain a contrary following.

Interestingly Onias appears in the rabbinic literature as Honi, but I don’t think there is any clear evidence that the rabbinic literature had any knowledge of John the Baptist. Or is my memory failing me?