Ever since my earlier post Why the Anonymous Gospels? Failure of Scholarship in Pitre’s The Case for Jesus I have intended to address Brant Pitre’s grossly misleading suggestion that all our earliest canonical gospel manuscripts come with the titles we know them by today — Gospel According to Matthew or simply According to Matthew…. etc. and that the argument that the gospels were anonymous until the end of the second century is baseless. Time and other things got in the way but then I read Bart Ehrman presenting the argument for the gospels being anonymous until towards 200 CE and thought that should save me the trouble. So below I have posted side by side Pitre’s and Ehrman’s respective arguments. (In places Ehrman appears to claim the argument as his own but in fact one finds it in works of earlier scholars, too.) I don’t claim to have covered all possible responses to Pitre’s assertions and suggestions in this post, but hopefully there is enough to make a sound assessment of his claims. Feel free to add other points.

| The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ / Brant Pitre | Jesus before the gospels / Bart Ehrman; The Anonymity of the New Testament History Books / Armin Baum; ….. |

| [I]n the last century or so, a new theory came onto the scene. According to this theory, the traditional Christian ideas about who wrote the Gospels are not in fact true. Instead, scholars began to propose that the four Gospels were originally anonymous. Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 13). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. It is especially emphasized by those who wish to cast doubts on the historical reliability of the portrait of Jesus in the four Gospels. The only problem is that the theory is almost completely baseless. |

In short, the Gospel writers are all anonymous. None of them gives us any concrete information about their identity. So when did they come to be known as Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John? I will argue they were not called by those names until near the end of the second Christian century, a hundred years or so after these books had been in circulation. Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 93). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. The first thing to emphasize about Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John is that all four are completely anonymous. The authors never indicate who they are. They never name themselves. They never give any direct, personal identification of any kind whatsoever. |

| I think most people would also view the anonymous biography with some level of suspicion. Who wrote this? Where did they get their information? Why should I trust that they know what they’re talking about? And if they want to be believed, why didn’t they put their name on the book? Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 12). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. It has no foundation in the earliest manuscripts of the Gospels, it fails to take seriously how ancient books were copied and circulated, and it suffers from an overall lack of historical plausibility. |

The anonymity of the New Testament historical books should not be regarded as peculiar to early Christian literature nor should it be interpreted in the context of Greco-Roman historiography. The striking fact that the New Testament Gospels and Acts do not mention their authors’ names has its literary counterpart in the anonymity of the Old Testament history books, whereas Old Testament anonymity itself is rooted in the literary conventions of the Ancient Near East. The Anonymity of the New Testament History Books: A Stylistic Device in the Context of Greco-Roman and Ancient near Eastern Literature; Author(s): Armin D. Baum; Source: Novum Testamentum, Vol. 50, Fasc. 2 (2008), pp. 120-142; Published by: Brill; Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25442594 |

| The first and perhaps biggest problem for the theory of the anonymous Gospels is this: no anonymous copies of Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John have ever been found. They do not exist. As far as we know, they never have. Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 16). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. the ancient manuscripts are unanimous in attributing these books to the apostles and their companions. |

It needs to be pointed out that we don’t start getting manuscripts with Gospel titles in them until about the year 200 CE. The few fragments of the Gospels that survive from before that time never include the beginning of the texts (e.g., the first verses of Matthew or Mark, etc.), so we don’t know if those earlier fragments had titles on their Gospels. More important, if these Gospels had gone by their now-familiar names from the outset, or even from the beginning of the second century, it is very hard indeed to explain why the church fathers who quoted them never called them by name. They quoted them as if they had no specific author attached to them. Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 105). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. |

| No Anonymous Copies Exist? | |

| First, there is a striking absence of any anonymous Gospel manuscripts. That is because they don’t exist. Not even one. Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 17). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. When it comes to the titles of the Gospels, not only the earliest and best manuscripts, but all of the ancient manuscripts— without exception, in every language— attribute the four Gospels to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. there is “absolute uniformity” in the authors to whom each of the books is attributed. In fact, it is precisely the familiar names of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John that are found in every single manuscript we possess! According to the basic rules of textual criticism, then, if anything is original in the titles, it is the names of the authors. 18 They are at least as original as any other part of the Gospels for which we have unanimous manuscript evidence. In short, the earliest and best copies of the four Gospels are unanimously attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. There is absolutely no manuscript evidence— and thus no actual historical evidence— to support the claim that “originally” the Gospels had no titles.

|

Pitre’s table in the left column leads readers to believe that we have Gospels of Matthew with headed by that title as early as the second century. Papyrus 4 in the literature (as reflected in the Wikipedia articles from which the images and captions below are taken) is in fact dated as likely from the third century. It contains a flyleaf of the title of Matthew’s gospel without any gospel text.

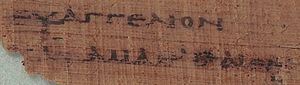

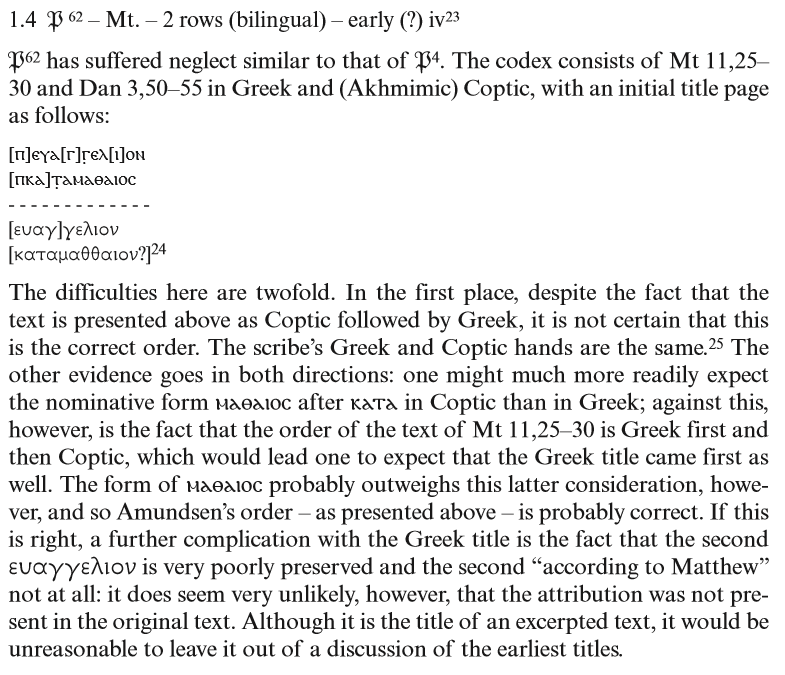

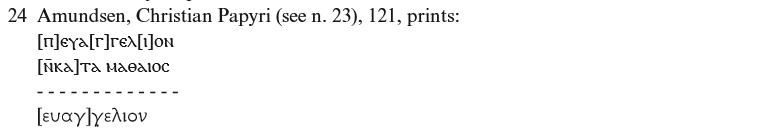

Papyrus 62 in the literature is generally dated to the fourth century.  Extract from Simon Gathercole’s ‘The Titles of the Gospels in the Earliest New Testament Manuscripts’, Zeitschrift für die neutestamentliche Wissenschaft 104.1 (2013), pp. 33-76.  |

| and this is important— notice also that the titles are present in the most ancient copies of each Gospel we possess, including the earliest fragments, Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (pp. 17-18). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. For example, the earliest Greek manuscript of the Gospel of Matthew contains the title “The Gospel according to Matthew” (Greek euangelion kata Matthaion) (Papyrus 4). Likewise, the oldest Greek copy of the beginning of the Gospel of Mark starts with the title “The Gospel according to Mark” (Greek euangelion kata Markon). This famous manuscript— which is known as Codex Sinaiticus because it was discovered on Mount Sinai— is widely regarded as one of the most reliable ancient copies of the New Testament ever found.

Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 18). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. The second major problem with the theory of the anonymous Gospels is the utter implausibility that a book circulating around the Roman Empire without a title for almost a hundred years could somehow at some point be attributed to exactly the same author by scribes throughout the world and yet leave no trace of disagreement in any manuscripts. 20 And, by the way, this is supposed to have happened not just once, but with each one of the four Gospels. |

There is one other reason for thinking that the Gospels did not originally circulate with the titles “According to Matthew,” “According to Mark,” and so on. Anyone who calls a book the Gospel “According to [someone],” is doing so to differentiate it from other Gospels. This one is Matthew’s version. And that one is John’s, etc. It is only when you have a collection of the Gospels that you need to begin to differentiate among them to indicate which is which. That’s what these titles do. Obviously the authors themselves did not give them these titles: no one titles their book “According to . . . Me.” Whoever did give the Gospels these titles was someone who had a collection of them and wanted to identify which was which. Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (pp. 105-106). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. |

| The Anonymous Scenario Is Incredible? | |

| Now, we know from the Gospel of Luke that “many” accounts of the life of Jesus were already in circulation by the time he wrote (see Luke 1: 1-4). So to suggest that no titles whatsoever were added to the Gospels until the late second century AD completely fails to take into account the fact that multiple Gospels were already circulating before Luke ever set pen to papyrus, and that there would be a practical need to identify these books. Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 21). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. |

In the various Apostolic Fathers there are numerous quotations of the Gospels of the New Testament, especially Matthew and Luke. What is striking about these quotations is that in none of them does any of these authors ascribe a name to the books they are quoting. Isn’t that a bit odd? If they wanted to assign “authority” to the quotation, why wouldn’t they indicate who wrote it? Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 93). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. This is true of all our references to the Gospels prior to the end of the second century. The Gospels are known, read, and cited as authorities. But they are never named or associated with an eyewitness to the life of Jesus. In these books Justin quotes Matthew, Mark, and Luke on numerous occasions, and possibly the Gospel of John twice, but he never calls them by name. Instead he calls them “memoirs of the apostles.” It is not clear what that is supposed to mean— whether they are books written by apostles, or books that contain the memoirs the apostles had passed along to others, or something else. Part of the confusion is that when Justin quotes the Synoptic Gospels, he blends passages from one book with another, so that it is very hard to parse out which Gospel he has in mind. So jumbled are his quotations that many scholars think he is not actually quoting our Gospels at all, but a kind of “harmony” of the Gospels that took the three Synoptics and created one mega-Gospel out of them, possibly with one or more other Gospels. 33 If that’s the case, it would suggest that even in Rome, the most influential church already by this time, the Gospels— as a collection of four and only four books— had not reached any kind of authoritative status. It is not until nearer the end of the second century that anyone of record quotes our four Gospels and calls them Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. That first happens in the writings of Irenaeus, whose five-volume work Against the Heresies, written in about 185 CE, It is striking that at about the same time another source also indicates that there are four authoritative Gospels. This is the famous Muratorian Fragment, This is remarkable. Before this time and place, nowhere are the Gospels said to be four in number and nowhere are they named as Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. |

| Why Choose Mark and Luke as Authors? | |

| The third major problem with the theory of the anonymous Gospels has to do with the claim that the false attributions were added a century later to give the Gospels “much needed authority.” 26 If this were true, then why are two of the four Gospels attributed to non-eyewitnesses? Why, of all people, would ancient scribes pick Mark and Luke, who (as we will see in chapter 3) never even knew Jesus? Pitre, Brant (2016-02-02). The Case for Jesus: The Biblical and Historical Evidence for Christ (p. 22). The Crown Publishing Group. Kindle Edition. |

That leaves the Gospel of Mark. One can see why the Gospel of Luke would not have been named after one of Jesus’s own disciples. But what about Mark? Here too there was a compelling logic. For one thing, since the days of Papias, it was thought that Peter’s version of Jesus’s life had been written by one of his companions named Mark. Here was a Gospel that needed an author assigned to it. There was every reason in the world to want to assign it to the authority of Peter. Remember, the edition of the four Gospels in which they were first named, following my hypothesis, originated in Rome. Traditionally, the founders of the Roman church were said to be Peter and Paul. The third Gospel is Paul’s version. The second must be Peter’s. Thus it makes sense that the Gospels were assigned to the authority of Peter and Paul, written by their close companions Mark and Luke. These are the Roman Gospels in particular. Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 111). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. The main reason there may have been reluctance to assign this book directly to Peter (the “Gospel of Peter”) was because there already was a Gospel of Peter in circulation that was seen by some Christians as heretical Acts is told in the third person, except in four passages dealing with Paul’s travels, where the author moves into a first-person narrative, indicating what “we” were doing (16: 10– 17; 20: 5– 15; 21: 1– 18; and 27: 1– 28: 16). That was taken to suggest that the author of Acts— and therefore of the third Gospel— must have been a traveling companion of Paul. Moreover, this author’s ultimate concern is with the spread of the Christian message among gentiles. That must mean, it was reasoned, that he too was a gentile. So the only question is whether we know of a gentile traveling companion of Paul. Yes we do: Luke, the “beloved physician” named in Colossians 4: 14. Thus Luke was the author of the third Gospel. 37 |

| Could Peter and John Even Write? | |

| Acts 4: 13 says [Peter and] John [were] literally “unlettered” (Greek, agrammatos)— that is, [they] did not know [their] alphabet. Ehrman, Bart D. (2016-03-01). Jesus Before the Gospels: How the Earliest Christians Remembered, Changed, and Invented Their Stories of the Savior (p. 93). HarperCollins. Kindle Edition. |

|

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

The table doesn’t fit the page.

Yeah, I can’t see Ehrman’s arguments. Good idea for a post though, I’ll be checking back to see when it’s fixed.

WARNING – As I post this I have a near irresistible urge to blurt out at any time, “Go home and get yer Fatah shinebox!”.

I posted at your special friend’s site:

http://www.patheos.com/blogs/exploringourmatrix/2016/02/brant-pitre-the-case-for-jesus.html#dq

“Oh there is Textual Criticism evidence that the Canonical Gospels had other attributions, you just have not listed it above:

GMark:

1) A Gnostic tradition that Glaucius was the interpreter/translator of Peter.

2) Which “Mark” wrote “Mark” = http://earlywritings.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=3&t=563

3) That Peter was the source for a Gospel that has a primary theme of discrediting him as a witness is ridiculous.

GMatthew:

1) Traditional attribution is based on the supposed tax collector “Matthew” within the Gospel but the source for the story gave the name as Levi (little known fact that Christianity changed the name because they thought “Levi” was “too Jewish”).

2) GMatthew wants to credit Peter as a historical witness but uses as a base a Gospel with a primary theme of discrediting Peter as a witness suggesting either there was no historical witness available to Matthew or it was not especially interesting and therefore not used.

GLuke:

1) We have an entire Church (Marcion) that used a version of Canonical “Luke” but did not attribute it to “Luke”.

2) For all we know Marcion’s version was original.

GJohn:

1) The orthodox testify that there were Christian groups c. 2nd century (Alogi) who did not think “John” was written by John.

2) We have external and internal evidence that “John” was originally Gnostic. Like GLuke, for all we know, Gnostic “John” could have been original.

Note that much of the above is Textual Criticism COMMENTARY regarding authorship which is exponentially weightier evidence than what extant individual manuscripts show.

Does his book mention any of this?”

http://thenewporphyry.blogspot.com/

Pitre wrote: “First, there is a striking absence of any anonymous Gospel manuscripts. That is because they don’t exist. Not even one.”

Perhaps an example could be P.Oxy. 76.5073, probably a Christian amulet, a rolled up strip likely worn around the neck. It contains Mark 1:1-2 and has a title from a different scribe:

αναγνωτι την αρχην του ευαγγελλιου και ιδε

“Read the beginning of the gospel and see”

http://163.1.169.40/gsdl/collect/POxy/index/assoc/HASHd905/06c1f0a5.dir/POxy.v0076.n5073.a.01.lores.jpg

It may be a special case. Nevertheless, it is called “the gospel” and not “the gospel of Mark”.

Very good. This post is going straight to the March 2016 Biblical Studies Carnival.