Russell Gmirkin in his new book, Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible draws attention to striking similarities between the Pentateuch (the first five books of the “Old Testament”) on the one hand and Plato’s last work, Laws, and features of the Athenian constitution on the other. Further, even the broader collection of writings that make up the Hebrew Bible — myth and history, psalms, wisdom sayings, moral and religious precepts, all presented with the aura of great antiquity — happen to conform to Plato’s recommendations for the sorts of literature that should form the national curriculum of an ideal state.

Russell Gmirkin in his new book, Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible draws attention to striking similarities between the Pentateuch (the first five books of the “Old Testament”) on the one hand and Plato’s last work, Laws, and features of the Athenian constitution on the other. Further, even the broader collection of writings that make up the Hebrew Bible — myth and history, psalms, wisdom sayings, moral and religious precepts, all presented with the aura of great antiquity — happen to conform to Plato’s recommendations for the sorts of literature that should form the national curriculum of an ideal state.

The idea that the Jewish scriptures owe their character and existence to the Hellenistic era, a time subsequent to Alexander’s conquests of the Near East, jars hard against traditional views of the origins of the Bible. Yet Gmirkin shows that many significant laws in the Pentateuch as well as the narrative style of their presentation are indeed closer to later Greek ideas than those found among Israel’s/Judea’s Syrian or Babylonian neighbours.

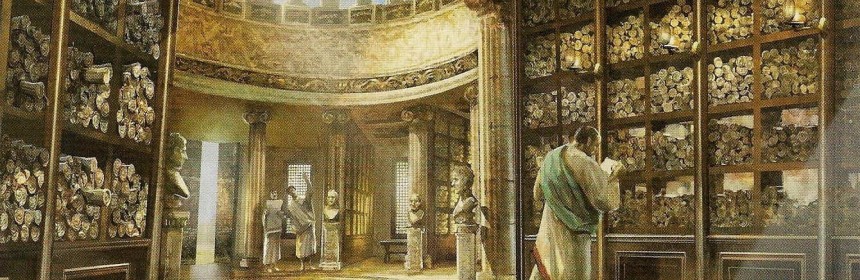

The key to this close linkage is the Great Library of Alexandria. Past studies exploring possible cultural contacts between the Greeks and Judeans prior to the Hellenistic era (that is, the period following Alexander the Great, from around 320 BCE) have generally shown that exchanges were primarily limited to trade and had minimal impact in the literary and philosophical sphere. On the other hand, we do know that Jews and Greek culture met in Alexandria. The history of the Athenian Constitution was available in the works of Aristotle there; Plato’s reflections on the ideal state and laws were also stored there. And the Hebrew Bible was said to have been translated into Greek there. Moreover, there is no external evidence for the existence of the Pentateuch prior to the Hellenistic era. In an earlier book, Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch, — see earlier Vridar posts — Gmirkin likewise argued that the Pentateuch was composed around 270 BCE and he introduces his new book as a sequel to Berossus and Genesis.

The main stimulus for Gmirkin’s new study is a desire to examine more closely some of the parallels presented by Philippe Wajdenbaum in Argonauts of the Desert: Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible. (Again, see earlier Vridar posts on Argonauts.) According to the Acknowledgements in Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible it was Thomas L. Thompson who suggested this study to Russell Gmirkin, and Gmirkin explains that his focus was on Wajdenbaum’s discussion of the parallels between Plato’s Laws and the Pentateuchal laws as the most persuasive section of his book.

While on the Acknowledgements, I have to refer to one other detail that struck me:

Many thanks . . . to both Greg Doudna and Daniel Samson for convincing me of the need to disseminate the results of my research outside of academia proper and laying out strategies to do so . . . .

That’s a nice sentiment. Unfortunately there is some way to go with the dissemination of the research beyond academia proper given its very hefty price tag. Even an electronic version costs around half of the hard copy price which still keeps it out of the financial range of most interested people. The traditional publishing model is going to have to break eventually.

I worry a little when I pick up a book that argues for a viewpoint I have been strongly partial towards. What if I am agreeing too quickly with its arguments because of my bias and overlooking the problems? (I also feel a little queazy, conflicted, when I receive a book gratis for review, as I did in this case.) Fortunately each chapter contains copious endnotes for me to follow up. Chapter two where the detail of the overall constitutional and governing structure implicit in the Pentateuch (and other sections of the Bible) is discussed has an endnote section larger by word count than the chapter contents. I can’t help myself. I take my time checking out those details. So it’s a slow read and I have only very superficially skimmed the remaining chapters at this stage.

As for the first chapter I need say little more since Russell Gmirkin has made it publicly available at academia.edu.

I’ll discuss chapter 2, “Athenian and Pentateuchal Legal Institutions”, in the next post.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- Questioning the Hellenistic Date for the Hebrew Bible: Circular Argument - 2024-04-25 09:18:40 GMT+0000

- Origin of the Cyrus-Messiah Myth - 2024-04-24 09:32:42 GMT+0000

- No Evidence Cyrus allowed the Jews to Return - 2024-04-22 03:59:17 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

I agree that academic titles are very expensive due to their limited sales, as opposed to popular general-interest books aimed at mass markets. I am glad that there is a more affordable Kindle version.

My efforts to disseminate the results of my research outside of academia proper are threefold.

(1) I am working on a popular book based on Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible.

(2) I have developed a catalog of lecture topics for either public or educational venues based on my current book. (See http://russellgmirkin.com/lectures.)

(3) And getting a copy of my book into your hands I thought was another good way to reach an intelligent, but not necessarily university audience.

Cheers

Russell Gmirkin

My day-job is about enhancing the value of academic research in part by making its outputs open access, or in cases where valid confidentiality reasons and cultural sensitivities prevent this, employing processes that enhance the awareness of the existence of the research and facilitate contacts with those involved. As such we are engaged with a variety of alternative models for academic publishing. Some of these models (not all of them, though, by any means) actually bypass the commercial publisher altogether. Others involve alternative means of meeting publisher costs and remuneration while making the published outputs freely accessible to the public.

The current situation is outrageous — where very often researchers have traditionally surrendered their own rights to their research outputs to commercial publishers who have been the ones to profit from work that was very often publicly funded in the first place.

We are in a time of change. Hopefully there will be steady progress for the democratization of knowledge, but no guarantees, unfortunately.

But I must add that one of the main reasons for starting Vridar was to share with a wider public knowledge of what was too often confined to academic audiences (especially but not only in the field of biblical studies) so I really do appreciate the opportunity to discuss your book.

I think you have a high quality blog that provides a positive public service by discussing academic topics within a wider audience. I think that’s terrific and I’m happy to interact with your blog via comments. I suspect that some other academics might think that’s a notch or two beneath them, What’s the point of academic knowledge that only benefits other academics!

That said, I only publish my research with traditional peer reviewed academic publishers and journals. Anything less would undermine the credibility of the research.

In my case all my research is neither university nor publicly funded and the royalty checks from academic publishers, who assume that all research is funded, borders on the laughable. As is well known, writers are the lowest form of literary life, and academic researchers the lowest form of writers. I’m sure the person who fetches lattes for my publisher is on a much higher pay grade than me, which is fine. My latest book, which you are blogging, is basically my gift to the world, five years solid research performed primarily to satisfy my own curiosity and to incidentally benefit humanity. I only mention this to clarify my position within the publishing food chain.

Best regards,

Russell Gmirkin

The so then, how does this all jive with the idea that the early Judeans were basically settled in the area by the Babylonians and given a history as a kind of backstory?

Yeh, I like that hypothesis, too. Now one day I’m going to have to sit down and study the ins and outs of the different scenarios and their supporting data and try to figure out what explanation (or collage of explanations) makes best sense . . . .

C’mon, we all know that Plato stole his best ideas from Moses.

Hi Neil, thanks for this interesting post.

I’m a bit surprised that also “the narrative style of their presentation” should be “indeed closer to later Greek ideas than those found among Israel’s/Judea’s Syrian or Babylonian neighbours”.

But this is not a critique, only a question. My own impression was always that the literary style of the Biblical narratives is usually completely different from the style of the Greek authors (more “clair-obscur”, more abstract, usually rather abridging, but not in the genealogies and so on).

I would be happy if you could give an example in a further post.

There are certainly differences between what I might generally call “Near Eastern” style and “Greek” literature — thinking specifically here of the anonymity of comparable literature.

I think R. Gmirkin’s point might best be spotlighted if we think of Hammurabi’s Law Code. That code is just a set of laws declared to have been blessed by the divinity. The laws of Moses come comfortably nested in a supportive narrative of origins extending from the Exodus to the conquest of Canaan. That latter presentation is the Greek style.

But I suspect I’m misunderstanding your point. Do persist if that is so.

Thanks. It seems that I misunderstood Gmirkin’s point. “The laws of Moses come comfortably nested in a supportive narrative of origins extending from the Exodus to the conquest of Canaan. That latter presentation is the Greek style.” I understand now what the argument is.

Hi Prof Gmirkin,

Can I ask you what you think about the historicity of Jesus ?

Thanks in advance

I’m afraid you’ll have to wait until the eventual publication of my book Josephus and the Historical Jesus.

Russell (not Prof, but thanks!) Gmirkin

I’ve read Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible once through, quickly, and I plan to do a more careful reading in the near future. I am actually combing through some key end notes to identify sources that I can review at the library of a local university.

Generally, the narrative style flows of Plato much better than in Berossus and Genesis, but I much prefer the footnotes of Berossus over the end notes of Plato. Also, I think some of the end notes of Plato contain information that more properly belong in the main narrative (which may explain the improved narrative flow).

The concluding chapter contains a fair number of speculative assertions, which I found surprising given the involvement of Thomas L. Thompson as editor. Also, the apparent reliance on the pseudepigraphic Letter of Aristeas for dating the formation of the Torah to circa 270 B.C.E. is suspect for a variety of reasons. That said, Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible provides more reason to believe that the Hebrew Bible was, indeed, a Hellenistic production.

I started reading Steve Mason’s A History of the Jewish War at the same time I was reading Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible, and I think the latter could have benefited from a discussion of how literature was produced and distributed in the Hellenistic Era similar to the discussion Prof. Mason provides about literature in ancient Rome in the former.

I look forward to your contributions to my posts on Plato/Hebrew Bible — corrections, additions, alternative perspectives, etc.

There was a discussion of this book (based solely on its brief press release) on Books Reddit. No one there was familiar with Gmirkin’s earlier book, nor any of the so-called minimalist scholars, and therefore were eager to dismiss the idea without so much as a glance at the free online chapter. The idea that the Pentateuch is “Old, Hebrew, and Oriental,” and entirely pre-dates the Greek literature of the Fifth and Fourth Century (and therefore cannot be influenced by it) is such an entrenched axiom, even among skeptics and secularists, that it may be hundreds of years before it can be shaken.

There is the additional problem that any such suggestion (i.e., that Biblical writers were influenced by Plato) is perceived as being an attempt to prove the Bible was a “hoax.” In reality, if it could be proven that such a proposition was in fact true, it would make the Bible an even *more* remarkable literary effort than it already is.

This is where the academy fails the public. N.P.Lemche wrote about the tactics of conservative scholarship and the effect of America’s dominance in the field and how these factors have held back a wider awareness of what the “newer” research has been saying: The Tactics of Conservative Scholarship (according to J. Barr & N-P. Lemche)

To repeat a story I have used before, I am dismayed at the way so many biblical scholars (at least those who promote their presence on the web) write dogmatically as if their own opinion is the only one worth considering and flatly dismissing or even misrepresenting alternative views. I keep thinking of a meeting I had with a professor of linguistics and asking him about Chomsky’s theory of universal grammar. The professor began by saying that “it depends on what school/arguments you agree with….” — and explaining the alternative viewpoints. Such academic honesty among so many biblical scholars (not all, of course) seems to be confined only to the more mundane questions.

Forgive my ignorance, but how does one pronounce Gmirkin?

Google it 😉

http://www.howtopronounce.co.in/gmirkin-in-english/

I’d tried that site, but for some reason I’m having no luck with the audio. I’m just going to go with ‘meer-kin’ till someone corrects me, I guess.

It sounds to me like gm (slight sound of a hard g in gm together as pl in police/please) … and then ir as in Fir or Fur.

That site is pretty hilarious. There are only 12 Gmirkin’s on the planet, at last count. How do they know how to pronounce my name?! They did a pretty fair job, though.

The pronunciation is G-meer’-kin, about two-and-a-half syllables. I can’t actually pronounce it in Russian, like my dear dead dad Vasia Gmirkin — they have a whole different set of sounds over there, rolling r’s and gutterals and suchlike. Just take a shot at pronouncing the G and I’m happy.

The site belongs to LexisNexis, the reputable publishers of legal resources. You’d think you could trust lawyers, now, wouldn’t you!

As a result of my ongoing conversations with an evangelical Christian friend, I have recently followed a series of lectures/presentations on Youtube from Israel Finkelstein, Richard Friedman and William Propp regarding the origins of the bible. They do not agree among themselves, but their analysis, based on a combination of archaeological and linguistic analysis places the sources at least hundreds of years earlier than the time of Alexander the Great.

How do you square these with the timing from (Mr.? Dr.?) Gmirkin?

I don’t believe the different views can be squared. I have disagreed with the Finkestein-Silberman view of biblical origins and the whole scenario of a Joshua-led renaissance: The Bible Unearthed, but still covering its non historical tracks. I wrote that some years ago so almost cringe at the thought of re-reading it now — but from memory I don’t believe my views of the fundamental point re biblical origins have changed.

Others like Philip Davies and Thompson (iirc) have argued for am early Persian era setting of the origins of what we recognise as the religion of Judaism and the earliest biblical literature. (Though Thompson has also pointed to details that do strongly suggest a Hellenistic perspective.)

Some, as we see here, argue for an even later time — the Hellenistic era.

I am open to both the views of the Persian and Hellenistic eras — I would need to do more thorough study on both before digging in and definitely siding with one or the other. Maybe after I complete Gmirkin’s book I can go back and have another look at some of the other arguments for the Persian era and then compare.

But Davies’ argument against the likely historicity of the Josiah reforms has been strong enough to make me very sceptical of Finkelstein’s and Silberman’s views. I do recall paying close attention to the archaeological evidence they cited to support their case and did consider it relatively light.

I am pretty much on board with Finkelstein and Silberman, as I think their archaeological pedigree is pretty strong. After listening to Friedman in this lecture, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H-YlzpUhnxQ, though, I have to admit that he has a point. These guys are no slouches, and the idea of a small but dominant sect coming out of Egypt and imposing its structure and theology on the Canaanites who were the original Hebrews makes a lot of sense historically, textually and archaeologically.

I would be interested to hear your take after you circle back.