The survey of Muslim religiosity was carried out in

- Indonesia,

- Pakistan,

- Malaysia,

- Iran,

- Kazakhstan,

- Egypt

- and Turkey.

It included statements on the respondents’ image of Islam. The survey listed forty-four items that examined religious beliefs, ideas and convictions. These statements were generated by consulting some key sociological texts on Muslim societies by authors such as Fazlur Rahman, Ernest Gellner, William Montgomery Watt, Mohammad Arkoun and Fatima Mernissi. Respondents were asked to give one of the following six responses to each of the statements presented: strongly agree, agree, not sure, disagree, strongly disagree, or no answer. More than 6300 respondents were interviewed. (Hassan, Inside Muslim Minds, p. 48)

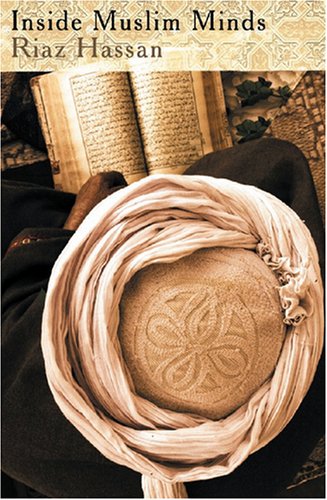

This is post #5 on Inside Muslim Minds by Riaz Hassan. We are seeking an understanding of the world. If you have nothing to learn about the Islamic world please don’t bother reading these posts since they will likely stir your hostility and tempt you into making unproductive comments.

We have looked at a historical interpretation of how much of the Muslim world became desensitized to cruel punishments and oppression of women and others. But what does the empirical evidence tell us? Here Hassan turns to a study explained in the side-box. Each question was subject to a score between 1 and 5, with “very strong” being indicated by 1 or 2.

Following are the 20 questions (out of a total of 44) that generated the highest mean scores.

Overall the results tell us that Muslims feel strongly about “the sanctity and inviolability” of their sacred texts. There is a strong belief overall that all that is required for a utopian society is a more sincere commitment to truths in those texts.

In other words, there is a large-scale rejection of modern understandings of the genetic and environmental influences upon human nature.

The evidence indicates very strong support for implementing ‘Islamic law’ in Muslim countries. (On “Islamic Law” see Most Muslims Support Sharia: Should We Panic?) Respondents strongly support strict enforcement of Islamic hudood laws pertaining to apostasy, theft and usury. The purpose of human freedom is seen not as a means of personal fulfilment and growth, but as a way of meeting obligations and duties laid down in the sacred texts. This makes such modern developments as democracy and personal liberty contrary to Islamic teachings. The strong support for strict enforcement of apostasy laws makes any rational and critical appraisals of Islamic texts and traditions unacceptable and subject to the hudd punishment of death. The strength of these attitudes could explain why hudood and blasphemy laws are supported, or at least tolerated, by a significant majority of Muslims. Strong support for modelling an ideal Muslim society along the lines of the society founded by the Prophet Muhammad and the first four Caliphs is consistent with the salafi views and teachings discussed earlier. (p. 54)

But notice: Continue reading “Something Rotten in the Lands of Islam”