We will have to build our new shelter. It will be a task spanning centuries. Many barracks have crumbled and will crumble before the solid, straight structure rises. We have to take our part in it.

We know the apparent failures of our predecessors. We are not discouraged by them.

The great romantics, Vigny, Lamennais, Michelet, Lamartine, Hugo were religious innovators, heretics, as one might have said in other centuries. They proclaimed the generous and confused gospel of new times. They did not establish anything visible. But the spiritual momentum they initiated will not stop. They have sounded the new Angelus.

Only Auguste Comte claimed to demolish Catholicism and rebuild it in three days. His dream seems childish. Yet, with profound instinct, he showed people what will probably be the object of the future religion: humanity.

Ernest Renan wanted to penetrate the origins of Christianity. He failed. His portrait of Jesus is as false and conventional as a painting by Ary Scheffer. He also wanted to turn the religion of science, which he shared with Taine and Berthelot, into dogmas. Today, scientism appears to be nothing more than a caricature of religion. But Renan’s work prepared for a sound and firm judgment on Christianity.

Alfred Loisy dreamed of reconciling Catholic dogma and historical criticism. He was harshly awakened. Patiently, he took up Renan’s program and Auguste Comte’s idea. He dissected the holy books of Christianity and outlined certain aspects of the religion of humanity.

Emile Durkheim attempted to explain the origins of religion. He too failed. His system was daringly built on too fragile foundations. But he ingeniously saw that religion is the primitive and necessary form that society took, and that the sacred is the social.

Shall we argue that these great failures should bring us back in submission to the withered bosom of the Church?

We would have to reject both the inconsistent and the solid, the sand and the stone.

No, the religious work of a century has not been entirely in vain. Holes have been dug, foundations laid, and a direction set. Through destruction and construction, something is happening. The spirit is in labor. Birth is foreseen.

Even if everything remains to be done, the efforts of the romantics, Comte, Renan, Loisy, and Durkheim would not be in vain. We cannot return to the old mistress of souls.

Her time was beautiful. Her time has passed. She is no longer what she was for forty generations of people: a closed universe, a safe haven, a haven of the spirit.

Poor, glorious old harbor! It held out against the winds and spray for a long time. Today, the dikes are submerged. The dismantled port has become the site of the worst storms.

If I were still willing to entrust myself to a submerged port, to a broken ship, if I still proclaimed myself a Christian, I would question myself in secret. I would thoroughly scrutinize my faith.

Is there a single fundamental dogma of Christianity to which, as a modern man, I can give my full acquiescence without hesitation?

Let’s go through them. There is no need for endless details. The views of reason are as quick as lightning.

Reason changes with every century because it is the living sum of human knowledge. Today it is less imbued with logic and algebra than in the 17th century. It has acquired a new acuteness since it forged the refined methods of historical sciences.

The problems that metaphysics has vainly pondered now arise from the perspective of history.

Let’s consider the essential questions: Scripture, Jesus, God. In the face of the Christian assertion, what is the immediate reaction of today’s reason?

The sacred character was initially attached to material objects: a tree, a stone, a spring. Transferring it to an intellectual object, such as the text of a book, was a tremendous advance in abstraction. It resulted in a great oppression of the mind, common to all religions of the book.

Is there, among books, a book that is not of man, a sacred book?

What prevents us from believing it is that we are beginning to see under what circumstances, by which priestly colleges, for what purpose, the parts of the Bible were successively declared sacred, and how theologians then disserted on the alleged divine inspiration. It is a very human history.

The circumstances that lead to the canonization of a book did not only occur among the Hebrews and Christians. The Persians before the Hebrews, and the Arabs after the Christians, had their sacred books. In this case, as in others, the sacred only expresses a social fact. How would today’s historian distinguish between the various sacred books of humanity?

The sacred character was initially attached to material objects: a tree, a stone, a spring. Transferring it to an intellectual object, such as the text of a book, was a tremendous advance in abstraction. It resulted in a great oppression of the mind, common to all religions of the book. A sacred stone will be revered in new ways over the ages. A sacred text imposes itself with a bruising rigidity. Three or four words from the Bible, ‘Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live,’ have endlessly provoked the massacre of women.

The critical study of the sacred books of the Old and New Testaments shows that most of them were composed in successive layers. The wondrous things people thought they would find there disappear upon examination.

It was admired that Isaiah had mentioned the name of Cyrus two centuries before Cyrus’s birth. This was because it had not been noticed that the Book of Isaiah is made up of two parts, separated precisely by those centuries.

It was astonishing that the wise Daniel could predict exactly the wars and marriages of the Seleucid kings, until it became evident that the author of the Book of Daniel lived during the reign of Antiochus Epiphanes.

Today, the true defenders of the Bible are those who find in it a rugged and proud testimony to humanity, not those who linger in search of enigmatic oracles.

These false wonders did a disservice to the Bible. Since we now see it as the literature of an ancient people, it has lost its divine character. It has gained powerful human interest.

Today, the true defenders of the Bible are those who find in it a rugged and proud testimony to humanity, not those who linger in search of enigmatic oracles.

Is there, among the men who have lived, a man of a different nature than all of them, a man-God?

The problem of Jesus is not resolved. Clarifying it will be one of the great tasks of our century. It is much more difficult than it seems.

So far, it has gone through four phases.

In the time of Renan and up until around 1900, it was believed possible to write a life of Jesus. This had to be abandoned. Critics recognized that there is a lack of materials for such an undertaking.

Then, immense efforts were made in Germany and France to extract a historical core from the gospel texts. What was believed to be known about Jesus was reduced to two traits: preaching the end of the world and being condemned to death in consequence..

This small historical core itself did not remain immune to criticism. Its determination is not without arbitrariness. The solidity attributed to it is only apparent.

In recent years, Germans have given up on knowing anything certain about Jesus. What we reach historically is not Jesus, but the early Christian groups. The idea they had of Jesus was not historical. It was subordinated to the cult they rendered to him and the divine legends that circulated in the ancient world.

Finally, others have wondered if Jesus is not a purely spiritual being. It is as God that he is attested from the beginning and has crossed the centuries. However high we go, we find him on altars, an object of worship. It is difficult to understand how he could have been made God from a man. It is easier to understand how God was humanized. After all, his earthly passion, passus sub Pontio Pilato, is just a dogma, inserted as such among others in the creed.

We cannot yet say to which final conception critical research will lead. But whether Jesus remains classified among men or among gods, he will be placed in a clear-cut category.

If he is a man, he is one of the messianic agitators of the 1st century of our era, and not the least chimerical, a Jewish martyr, and not the most touching, a rabbi of Israel, and not the wisest.

If he is God, he stands beside, or rather, above the other dead and resurrected gods. He is God who suffers. He is the most moving divine figure that suffering humanity has produced.

As for the idea of a God-man, it’s a confused idea, a behemoth like the centaur, which we’re forced to disentangle.

A man could have been deified, by an uncommon aberration of religious sentiment. A god could have been endowed with a human face and earthly adventures by the infinite fertility of religious imagination. In the first case, Jesus is a false god. In the second case, he is a false man. Man-God is an unthinkable thing, a purely verbal compound.

Obscure man or splendid God, Jesus will take his place in the line of men or in the line of figures created by humanity.

Jesus has everything to lose by being registered in the annals of history. Those who deny his historical existence will remain the only ones able to defend his spiritual reality.

He has everything to lose by being registered in the annals of history. Those who deny his historical existence will remain the only ones able to defend his spiritual reality.

Is there, in the world and beyond the world, a single and personal God who, among the peoples, saves only one people: the Jews in the past, the Christians today?

What prevents us from believing …. is a knowledge of history.

What prevents us from believing this is not a philosophy of the world, but a knowledge of history.

The old philosophical problem of the existence of God loses its interest as soon as we historically perceive the birth of God.

The supreme God whom Christians worship, on whom philosophers speculate, has historical origins. It is the ancient god of Israel, the barbaric Yahweh.

He was first a small god of the desert, a djinn, the local genius of a spring in a dreadful valley. He only had real existence during seasonal festivals when nomads, grouping their tents around the spring, created him. They believed they had captured his name, lah, lahou, or lahvé. Lots were cast to summon his judgment. Some very simple wishes were attributed to him, forming a small code. By accepting these rules, one was considered to make an alliance with him.

Mercenaries who escaped from Egypt and returned to a nomadic life made an alliance with him and formed a people around him.

When these insatiable Hebrews attacked Canaan, they believed they were taking Yahweh with them in a portable chest. They attributed their successful actions to him.

As soon as they were established, Yahweh became a Baal, that is, a land-owning god. He was endowed with temples, land, slaves, sacred prostitutes, and prophets. He usurped Babylonian cosmogonic legends that made him the creator of heaven and earth.

In the spiritual history of humanity, there is no greater episode than the rise of this god. One of the most recent and humblest among the gods, he managed to eliminate all the others in the West.

The power of a god lies in the faith one devotes to him. It is most evident in defeat. Yahweh grew through tremendous defeats.

His followers were torn apart by schism and almost annihilated. He was left with only one temple, that of Jerusalem. This was the basis of his glory. The god of the single temple began to be conceived as the one God.

Then he was completely defeated by the god of Babylon, Bel-Marduk. His temple was destroyed, his people partly exterminated, partly enslaved. It was then that he rose to the highest.

A prophet-poet whose name is unknown and whom we call the Second Isaiah formulated monotheism. Yahweh is not only superior to the other gods, he alone is God. The conqueror Cyrus, who does not know him, is nevertheless his instrument. An unprecedented idea.

God was born. It is a date in human history. The Second Isaiah founded Judaism, Christianity, and Islam in one stroke. Judaism, which he transformed from a national religion into a catholic religion. Christianity, because in a mysterious part of his poem, he outlined the figure of the Servant, martyr and redeemer, an early version of Jesus. Islam, which is only a repetition of the monotheistic message.

A solemn date! At the same time, in the sixth century BCE, Confucius and Laozi gave China the rites of wisdom, India was stirred by the immense Buddhism, Zarathustra in Persia changed a religion of princes into a religion of peasants, and Pythagoras in the West reformed the mysteries. And the Second Isaiah proclaimed a unique God destined to conquer half the world.

It seems that the entire planet is setting its religious destiny for a long time to come. It’s like the passage of a celestial body.

After the major religious reforms of the sixth century, the Christian revolution is secondary. Its main effect was to make the monotheism of Israel acceptable to the Western world by adding a myth of redemption.

Today, the idea of a single God has become so natural to us that we believe it to be essential to religion. It is not. In Buddhism and Confucianism, the idea of God or gods plays almost no role. An atheistic religion is perfectly conceivable. . . . Monotheism is neither truer nor more moral than polytheism.

Today, the idea of a single God has become so natural to us that we believe it to be essential to religion. It is not. In Buddhism and Confucianism, the idea of God or gods plays almost no role. An atheistic religion is perfectly conceivable.

Monotheism is neither truer nor more moral than polytheism. It is a mental habit, a way of speaking. It is a religious imagination that seduces with apparent simplicity and disappoints in the end if asked for a profound explanation of things.

God, in whom we are accustomed to symbolize the absolute, is the invention of a time and a place. It has intimate connections with ancient Palestine and the city of Jerusalem.

Around the hollow rock that bore the altar of burnt offerings, humble singers composed the Psalms that are endlessly repeated in all Western temples today. The Song of Solomon was murmured there for the first time so that, centuries later in Spain, Saint Teresa and thousands of women would be intoxicated by it.

In the countless Jewish, Christian and Muslim minds for whom Jerusalem is still a holy city, God exists

But His credit, compared to what it was in past centuries, has diminished.

All the great religious movements that began in the sixth century BCE have either exhausted themselves or seem to be declining.

God is fading.

Will the celestial body pass by again?

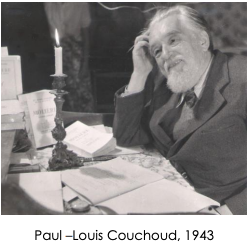

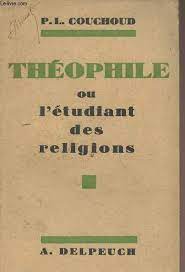

Couchoud, Paul Louis. Théophile ou L’étudiant des religions. Paris: André Delpeuch, 1928. pp 219-231 (Highlighting of selected quotations are my own additions)

Recent discussions have sent me back to a second look at Aviezer Tucker’s Our Knowledge of the Past. (I posted about this book back in 2013.) A detail I had forgotten in the meantime is Tucker’s interesting explanations about when a consensus is more likely to be trustworthy than not. Here is part of what he writes:

Recent discussions have sent me back to a second look at Aviezer Tucker’s Our Knowledge of the Past. (I posted about this book back in 2013.) A detail I had forgotten in the meantime is Tucker’s interesting explanations about when a consensus is more likely to be trustworthy than not. Here is part of what he writes: