Our quest is to test the thesis that the earliest books of the Bible were written or at least heavily redacted and supplemented in the Persian period. To that end we have been trying to understand what Persian era candidate “biblical” societies were like. We’ve looked at Judeans in Persian times according to the evidence in both the Persian province of Yehud and their “brethren” in Egypt, so for the next stop we will have a look at the “Samarians”. Samarians may seem unusual against our more familiar Samaritans . . .

The Samarians (no “t”) of the Persian period are not to be confused with the Samaritans of the first century CE. (Betlyon 27)

We are talking about the people who inhabited the “biblical northern kingdom of Israel” after the biblical united kingdom of David and Solomon divided between “Israel” in the north and “Judah” in the south. After the Assyrians conquered the northern kingdom they established in its place the province of “Samerina”, but in subsequent Persian times we speak of the Samarians.

Samaria, though subservient to imperial overlords, continued to be a major administrative centre.

When Persia conquered Babylon in 539 BCE, Cyrus and his successors retained Samaria as the administrative center in the “Province Beyond the River [Euphrates]” and placed it under the governorship of Sanballat. Excavators have discovered a large garden area (.25 m-thick; 45 x 50 m) that surrounded the district governor’s palace there. A fifth-century Athenian coin, three Sidonian coins from the reign of Abdastart I (370-358 BCE), fourteen Aramaic ostraca, plus significant quantities of pottery imported from Aegean centers during the late sixth to late fourth centuries BCE . . . all attest to the solvency of the Ephraimite economy . . . . (Tappy 583)

Coins

Ancient coinage in general can provide significant information not only about the economic, but also the political, cultural and religio-historical state of affairs of a city or province. Coins were commissioned by those in power, were often used to communicate specific values and ideas and served as mass medium in Antiquity. Accordingly, the images appearing on them were not randomly chosen but selected with great precision and reflect a certain ‘spirit’. (Wyssmann 222)

The sampling here is taken from Wyssmann’s study and were selected on the basis of having been more probable than not minted in the province of Samaria itself. The inscriptions on Samarian coins were in Aramaic, Paleo-Hebrew and Greek letters. Greek gods appear along with names of Persian satraps and Samarian governors.

These images have been selected from Wyssmann, Patrick: “The Coinage Imagery of Samaria and Judah in the Late Persian Period” 2014.

The Wadi Daliyeh finds

The Samaria papyri from Wadi Daliyeh provide us with precious information regarding some of the inhabitants of Samaria, including some of its officials. (Dušek 2020, 2)

The cache of papyri, coins, jewelry, pottery were deposited in a cave in Wadi Daliyeh by people fleeing from Samaria as Alexander the Great was on his way back there after the city had rebelled against his recent conquest by burning his appointed governor alive (according to Josephus). Those who hid in the cave were probably found and suffocated by a fire Alexander’s troops lit at the cave’s entrance.

The following notes are taken from Dušek 2007:

- Names on the papyri contain theophoric elements relating to Yahweh (mostly) but also El, Ab, Nabu, Shamash, Sahar, Šalman, Bel, Baga, Sîn, Baal, Isis, Ilahi et Qôs.

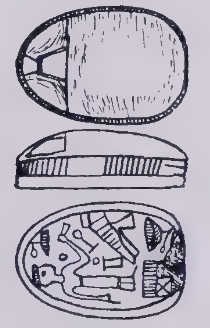

- Clay seals include images of Hermes, Heracles and Perseus.

The following images are from Lapp, Paul W., and Nancy L. Lapp, eds. Discoveries in the Wadi Ed-Daliyeh. American Schools of Oriental Research, 1974.

According to the onomastics of the Wadi Daliyeh manuscripts, the population of the province of Samaria would have been quite diverse: most of the names are Yahwist; in the other names, the theophoric elements El, Ab, Šamaš, Sahar, Bel, Baga, Sîn, Nabu, Šalman, Ba’al, Isis, Ilahi and Qôs refer to West Semitic, North Arabic, Aramaic onomastics, Hebrew, Babylonian, Phoenician, Egyptian, Persian and Idumean. We also identified a possible Assyrian name and a name expressing ethnic origin. As we have suggested, not all of these people were likely inhabitants of the province of Samaria; in certain cases it may have been merchants who were traveling, or slaves sold in Samaria, but originating from other provinces. The variety of the population of the province of Samaria can be explained on the one hand by the great prosperity of the region and by political stability which favored settlement in the territory of the province, and on the other hand by the deportations of populations in the province of Samaria before the Persian era. (Dušek 2007, 601 – translation)

Mount Gerizim

One of the most astonishing discoveries was unearthed by a team of archaeologists led by Yitzhak Magen, who excavated a site in Samaria at Jabal al-Tur, one of the three peaks of Mount Gerizim, from 1982–2006. They identified a Yahwist sacred precinct active from the 5th century BCE until its destruction in the mid–late 2nd century BCE.4

4 It is unclear if this sacred precinct included an actual temple building, despite the suggestions of the excavators in Magen, Mount Gerizim Excavations Volume II . For further discussion, see Pummer, “Was There an Altar?”. (Economou 155)

That’s another topic, though.

Betlyon, John W. “A People Transformed Palestine in the Persian Period.” Near Eastern Archaeology 68, no. 1/2 (2005): 4–58.

Dušek, J. Les Manuscrits Araméens Du Wadi Daliyeh Et La Samarie Vers 450-332 Av. J.-C. Leiden ; Boston: BRILL, 2007.

Dušek, Jan. “The Importance of the Wadi Daliyeh Manuscripts for the History of Samaria and the Samaritans.” Religions 11, no. 2 (January 29, 2020): 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11020063.

Economou, Michael. “The Aramaic Inscriptions from Mount Gerizim: Production, Identity, and Resistance.” Journal of Ancient Judaism 15, no. 1 (October 16, 2023): 154–73. https://doi.org/10.30965/21967954-bja10032.

Lapp, Paul W., and Nancy L. Lapp, eds. Discoveries in the Wadi Ed-Daliyeh. American Schools of Oriental Research, 1974. http://archive.org/details/discoveriesinwad0041delb.

Lemche, Niels Peter. “Samaritans in History and Tradition.” In Samaritans and Jews in History and Tradition, by Ingrid Hjelm. Taylor & Francis, 2024.

Tappy, Ron E. The Archaeology of Israelite Samaria. Volume 2: The Eighth Century BCE. Brill, 2001.

Wyssmann, Patrick. “The Coinage Imagery of Samaria and Judah in the Late Persian Period.” In A “Religious Revolution” in Yehûd? The Material Culture of the Persian Period as a Test Case, edited by Christian Frevel, Katharina Pyschny, and Izak Cornelius, 221–66. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 267. Fribourg: Academic Press, 2014. https://www.academia.edu/9216977/The_Coinage_Imagery_of_Samaria_and_Judah_in_the_Late_Persian_Period.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

What I find fascinating is the likely depiction of an asherah on a fourth century BCE coin from Samaria, as I discuss in a forthcoming book:

• A key aspect of the Iron II cult of Asherah was a pole or rod. A contemporary representation of this rod appears at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud, where a picture of a stylized sacred tree flanked by ibexes appears on Pithos A where it is thought to represent Asherah as a fertility goddess (Leith 2014: 276; Asherah is associated with flocks of sheep or goats at Deut. 7:13; 28:4, 18, 51). This sacred tree corresponds in great detail to the blooming rod of Aaron, the symbol of his priesthood, with its buds, blossoms and almonds (Num. 17:8), which was laid up in the sacred ark in the tabernacle (Num. 17:10; cf. Heb. 9:4). “It is difficult to imagine a more precise pictorial representation of the object described verbally in the Pentateuchal account than this drawing. The central element of the drawing plainly resembles a staff. It is adorned with six buds alternating with eight blossoms. And at the top are two elements shaped like almonds in the shell and speckled with dots that match the pockmarks typical of these shells.” (Eichler 2019: 36.) It would appear that the Priestly author, perhaps along with Ezekiel, did not find the Asherah objectionable, and included this flowering staff among the most precious contents preserved in the sacred ark (Eichler 2019: 40-41). This sacred staff later featured in the account of Moses striking the rock to obtain water in Num. 20:1-13 (Eichler 2019: 41-45). The sacred tree flanked by rampant goats is an image that also uniquely recurs in fourth-century BCE Samarian coinage, along with other imagery also depicted at Kuntillet ‘Ajrud (Leith 2014). This seems to indicate the persistence of the Asherah as revered sacred tree at a late date in Samaria.

Eichler, Raanan. “The Priestly Asherah.” VT 69 (2019): 33-45.

Leith, Mary Joan Winn. “Religious Continuity in Israel/Samaria: Numismatic Evidence”. A “Religious Revolution” in Yehûd? The Material Culture of the Persian Period as a Test Case. Christian Frevel, Katharina Pyschny and Izak Cornelius (eds.), 267-304. Göttingen: Academic Press, 2014.

Well I sure overlooked that one, didn’t I! Thank you for adding this to the post.

What is also interesting is the way that the lampstand in the tabernacle (Ex 25:31-36), with its branches and almond embellishments has a clear connection with both Aaron’s staff and the Asherah of Kuntillet ‘Ajrud. It also differs from them in that it is made of solid gold rather than wood – which may be significant. I suspect that the lampstand is a denatured and domesticated version of asherah/Asherah – transforming it from respresentational icon to functional furniture.

I’m looking forward to what you have to say about the temple on Mt. Gerizim, especially in view of the temple in Elephantine, the correspondence between Elephantine and Samaria regarding the temple in Elephantine, and the implications of both on the narrative of Ezra-Nehemiah.

I’d love to — but my inability to access volumes 1 and 2 of Yitzhak’s Mount Gerizim Excavations has meant I have had to shelve that project.