No, this post is not about the Testimonium Flavianum, that disputed passage about the “crucified-under-Pilate-Jesus”. It is about other figures in the works of Josephus that various authors have proposed are the original persons from whom the Christian myth was derived. Possibly the most well-known one that comes to mind is Jesus ben Ananias, the “mad man” who cried Cassandra warnings of doom on the city of Jerusalem before being hit with a stone catapulted by the Romans. Others have embraced the possibility that an earlier person, Jesus ben Saphat, was the “original Jesus”. His scene was in the Galilee area where he castigated wayward rivals by appealing to the Law of Moses and attracting “low-class” followers like “seamen” before making a fateful journey to Jerusalem. Another view sees Josephus’s account of “the Egyptian” as the true original. He gathered followers at the Mount of Olives outside Jerusalem before meeting his demise. Others have even argued for the Roman military commander, Titus, as the template for details in the gospel narratives. One such view interprets Jesus’ call to his disciples to “fish for men” as an ironic twist on the moment when Romans butchered rebels who had fled into the lake of Galilee.

I wonder if the ability to identify different persons acting out scenarios that remind us of this or that in the gospels is because the first evangelist, in seeking a way to frame the first story about a life of Jesus, drew inspiration from, among other sources, what he had read in works by Josephus.

Some readers will feel uncomfortable with such an idea because it would mean the first gospel was not composed until the last few years of the first century at the earliest. Might not the author have been drawing on his memory of persons and events quite independently of any reading of Josephus, and if so, have even written the gospel before Josephus wrote Antiquities? Different readers will come to different conclusions on the likelihood of that explanation.

Let’s have a closer look at some of these purported precursors of the gospel Jesus.

Jesus son of Ananias

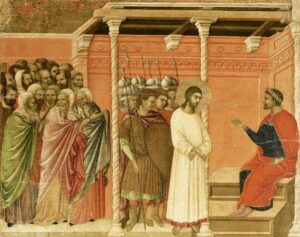

The scholar and churchman Theodore Weeden is associated with many parallels between Jesus ben Ananias and the gospel Jesus. I have set out his 23 points of parallel items on a separate webpage: http://vridar.info/xorigins/josephus/2jesus.htm This Jesus made a nuisance of himself by crying “Woe Woe to Jerusalem”, its people and its Temple but was dismissed as a harmless madman by a Roman authority before meeting his fate. You can read the other details set out in two columns on the linked page. Some of the more significant incidents in common include the presence of Jesus ben Ananias in the Temple prior to his death, his quotation of Jeremiah, his silence before his Roman interrogator, his subsequent flogging and loud cry at his death.

The scholar and churchman Theodore Weeden is associated with many parallels between Jesus ben Ananias and the gospel Jesus. I have set out his 23 points of parallel items on a separate webpage: http://vridar.info/xorigins/josephus/2jesus.htm This Jesus made a nuisance of himself by crying “Woe Woe to Jerusalem”, its people and its Temple but was dismissed as a harmless madman by a Roman authority before meeting his fate. You can read the other details set out in two columns on the linked page. Some of the more significant incidents in common include the presence of Jesus ben Ananias in the Temple prior to his death, his quotation of Jeremiah, his silence before his Roman interrogator, his subsequent flogging and loud cry at his death.

I find it hard to imagine this particular figure having any historical existence at all. He appears amidst a list of divinely sent signs that Josephus says were harbingers of the city’s destruction. He looks very much like a stock figure of doom, of a Cassandra figure whom people are ordained to ignore and mock but only to their own peril. Hence I have doubts about the view, that some have expressed, that the evangelist responsible for the Gospel of Mark was drawing on memory of a real figure. If Josephus was the source of the figure then yes, the first gospel was indeed written later than commonly said.

The parallels are too many and specific to be discounted as coincidence. I can imagine our evangelist taking the model of ben Ananias — his assumed madness, his prophetic declaration of doom, his silence at his trial, his being flogged — and relating some of those sorts of details to what he was imagining about Jesus from the Scriptures: rejection by his own family, as Isaiah’s Suffering Servant being silent before his accusers, and so forth. The Jewish Scriptures presented him with a theme, a motif, but a relevant narrative application inspired by Josephus, modified for his new setting, of course, assisted with fleshing out a narrative context for those themes.

Jesus son of Saphat / Sapphias

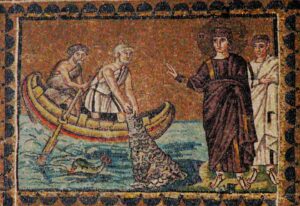

Frans J. Vermeiren in A Chronological Revision of the Origins of Christianity argues that beneath the peaceful gospel Jesus lies a darker, more violent figure: think of his saying about “not coming to bring peace but a sword”, his assault on the temple, the fleeing herdsmen from the scene where Jesus confronted “Legion”, and so forth. From this perspective, Vermeiren sees the various references to the rebel military leader Jesus ben Saphat in Josephus’s writings as significant. This Jesus was active in Galilee. His followers were the lower class, including sailors.

Frans J. Vermeiren in A Chronological Revision of the Origins of Christianity argues that beneath the peaceful gospel Jesus lies a darker, more violent figure: think of his saying about “not coming to bring peace but a sword”, his assault on the temple, the fleeing herdsmen from the scene where Jesus confronted “Legion”, and so forth. From this perspective, Vermeiren sees the various references to the rebel military leader Jesus ben Saphat in Josephus’s writings as significant. This Jesus was active in Galilee. His followers were the lower class, including sailors.

Even though this Jesus was certainly a historical figure might we not imagine a similar influence as with Jesus ben Ananias at work on the creative mind of the gospel author? The idea of Galilee as a setting may have already been floated through a prophecy in Isaiah 9 (though it is not until Matthew that we find an explicit appeal to this passage as the source for the narrative setting); if so, then one can imagine his ears pricking up when he hears about another Jesus who gathered followers in Galilee. When he learned from Josephus that this same Jesus appealed to the Law of Moses when castigating his countrymen then surely he, the author, must have turned over such a figure and event in his mind. The gospel Jesus was to be the origin of the new “philosophy” or what became Christianity, so the idea of twelve disciples surely came to him from his reading of the twelve sons of Israel who became the founding fathers of the twelve tribes of Israel. But did the idea of making the first of those disciples of the new Jesus’ “fishermen” derive from the Josephan rebel’s followers including many “sailors”? Is that why we have come to read of Jesus walking along the shore to find and call his first disciples?

There were numerous literary precursors for a travel narrative available to our author but one can imagine him reading of Jesus’s flight from Galilee, probably to Jerusalem, as having some creative influence as well.

The Egyptian

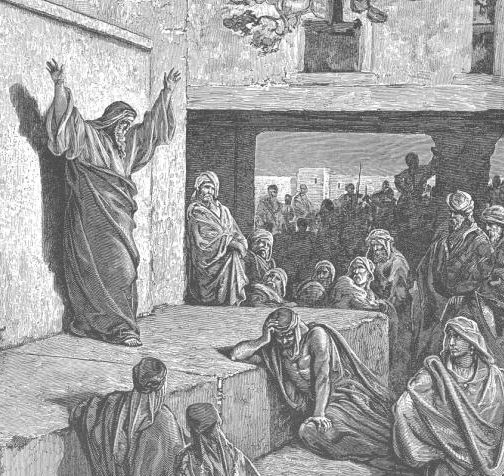

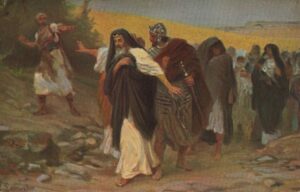

We have discussed Lena Einhorn’s Shift in Time thesis in other posts. In one of those posts, we focused on Josephus’s account of a false prophet, known to be a magician, and an Egyptian, who called his followers to the Mount of Olives. From there, he promised them, they would see the walls of Jerusalem collapse as they had done for Joshua (=Jesus).

We have discussed Lena Einhorn’s Shift in Time thesis in other posts. In one of those posts, we focused on Josephus’s account of a false prophet, known to be a magician, and an Egyptian, who called his followers to the Mount of Olives. From there, he promised them, they would see the walls of Jerusalem collapse as they had done for Joshua (=Jesus).

Now the evangelist had the model of the OT messianic figure, David, ascending the Mount of Olives in deep grief, fearing for his life, pursued by his enemies (2 Samuel 15). Yes, the biblical models for a suffering messiah were there, but how to fit these models into a new narrative for the one to become the “mother of all Messiahs”? I can imagine this author thinking about that more recent calamity befalling a prophet on the Mount of Olives. Yes, that would be an idea: let his Jesus who has travelled from Galilee pronounce destruction on the city of Jerusalem and on the eve of his fate he also, at that moment, walks up the Mount of Olives with his disciples.

Einhorn further explores the possible significance of Josephus describing a Theudas, active in the Jordan River region and who was beheaded, prior to the Egyptian episode. Again, it is not hard to imagine one looking for a new narrative to associate some of this detail with a sub-plot of the precursor of his new Jesus.

Conclusion

I have not covered in depth any of the cases that have been made for the Josephan figures pointing to “the real Jesus” behind the Jesus of the gospels. I confess I have found each of the above hypotheses that attempts to establish its respective figure as the original Jesus lacking when it comes to explaining how the details of the story changed into what we read in the gospels today. If, however, we begin with our first evangelist filled with biblical interpretations and motifs (silence before accusers, ascending the Mount of Olives, calling followers) is it not easier to conceptualize the relevance of the Josephan passages for helping him flesh out those isolated ideas into a coherent narrative?