Other posts arguing against the view that Second Temple Jews were longing for the appearance of a messiah:

Were Jews Hoping for a Messiah to Deliver Them from Rome? Raising Doubts (2019-05-07)

“The Chosen People Were Not Awaiting the Messiah” (2019-05-05)

Myth of popular messianic expectations at the time of Jesus (2017-02-03)

Questioning Carrier and the Conventional Wisdom on Messianic Expectations (2016-08-02) – annotated links to six other posts addressing the question.

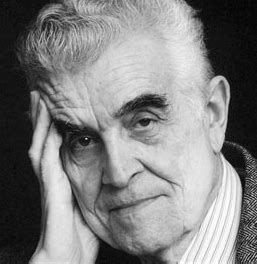

Having questioned the common notion that Jesus made his appearance in a society pining for the coming of a deliverer to free the Jews from Rome, I was happily surprised to see further arguments against the same common idea set out 180 years ago in an appendix to a multi-volume work on the gospels written by Bruno Bauer.

I have posted the translation below but for those in a rush here are the key takeaways:

- – A survey of the Second Temple literature demonstrates a distinct lack of interest in the idea of a literal Davidic messianic figure about to appear in the future. [Bauer was writing before the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls but see the posts in response to Richard Carrier in the side box for what other scholars have had to say on that so-called evidence for popular messianism.]

- – If Judeans had developed ideas about a coming messiah from their prophetic texts we would expect to see in the gospels some reference to stock ideas from those supposedly widespread ideas. Instead, the gospel authors are “winging it” — they come up with different possibilities for interpreting Old Testament passages as messianic and are evidently not tapping in to common ideas supposedly extant at the time. They are creating the prophetic interpretations, not inheriting common stock.

- – History-changing personalities have always made their impact by the originality of their ideas and presence; they have not made a splash by claiming to be a popularly pre-figured person.

Here is the full translation of Bauer’s discussion in the first volume of Critique of the Gospel History of the Synoptics (1841) [=Kritik der evangelischen Geschichte der Synoptiker]

I have added sub-headings to make it easier to focus on points of particular interest.

The Messianic Expectations of the Jews at the Time of Jesus

All those who have spoken out against Strauss’s interpretation of the evangelical history in recent years also felt it was their duty to protest against the derivation of sacred history from the Messianic expectations of the Jews. But this protest, no matter how earnestly intended or spoken with holy disgust at the supposed blasphemy, was from the beginning powerless and remained so, since it could not prevent Gfrörer from developing the contested view to the extreme that it could reach. But what use was it to recall that this or that Jewish book, which the critic designated as a source for the views of the evangelists, was written six, seven, or fourteen centuries after the composition of the Gospels? What could an argument of this kind achieve, which only focused on individual and few points, if one shared with Strauss the basic assumption that Messianic expectation had already prevailed among the Jews before the appearance of Jesus, and even knew fairly accurately what its nature was? To the same extent, a dispute of this kind had to be futile and useless, just as it was impossible for Strauss to make the origin of the evangelical history understandable, as long as he, like Hengstenberg, considered the Messianic dogma of the Jews as one that had already been fully developed before the appearance of Jesus. Both criticism and apologetics shared the same error, their struggle could only lead to unfruitful quarrels, but not to a decision, and the matter suffered most – it remained buried in prejudices.

392

Since Gfrörer has now taken uncritical thinking to its peak, it is finally time to come to our senses and to recognize reason, which has not yet come to recognition in this regard after two thousand years of error in history. It is a matter of the utmost importance – who does not immediately sense it? – to bring criticism to its ultimate crisis and to make it the last judgment of the past by elevating it to complete ideality and universality and freeing it from the last unrecognized positive with which it has still been entangled. The last and most persistent assumption that it still shared with apologetics must be addressed – and how extraordinary is the reward that follows the resolution of this uncritical assumption when the creative power is again attributed to the Christian principle, which even the previous criticism had denied.

Thinking the unthinkable

Apologetics, as it has developed or rather remained the same since the beginning of the Christian community until our day, could not even conceive the idea that it might be possible to question whether the Messiah’s view had become a reflection concept before the time of Jesus and had come to power as such. It couldn’t – because it is already clear to them from the outset that the content of the revelation has always been the same and always the same one object of consciousness *); it must not – because in its limited polemical interest, it believes that the connection of the Old and New Testament is only ensured if it demonstrates the content of the latter as a real object of consciousness in the former. To interpret the preparation of Christianity differently, namely to say that Jesus only had to say: “See, I am what you have been expecting so far” – this is completely impossible for them.

*) The author allows himself to refer to the detailed explanation in his presentation of the Religion of the Old Testament, section 54.

393

Even Strauss shared the apologist assumption

Until now, it was impossible for criticism to free itself and history from the apologetic shackles, as every opposition in its first form shared the assumptions of its opponent and only determined them differently. Hengstenberg and those before him claimed that in Jesus, what the pious had hoped and expected had appeared, while Strauss claimed that in the Christian community, the history of Jesus had been created and elaborated as an image and fulfillment of Jewish expectations.

Intent to produce evidence

After having proven in the above criticism that the gospel history has its principle solely in Christian self-consciousness, and that its assumptions, as far as they are contained in the Old Testament, were only used by the community and the evangelists as these assumptions for the elaboration of the Christian principle and the messianic image, we want to provide evidence in outline that the messianic element of the Old Testament view did not develop into a reflection concept before the beginning of the Christian era.

It is not necessary to mention here in more detail that the messianic views of the prophets had not yet been raised by them to the unity and solidity of the concept of reflection; we have proven this in our presentation of the religion of the Old Testament. The interest of the present investigation lies solely in the question of whether the idea of “the Messiah” had prevailed among the Jews in the centuries immediately preceding the advent of Jesus.

The Numbers prophecy of Balaam

If we first examine the Septuagint, whose oldest components are said to date back to the third century BC, and Jonathan’s paraphrase, we have an example of what a translation of the Old Testament must look like when it is written in a time and environment where “the Messiah” has become the subject of consciousness and the view has become dogma. The translator must indicate explicitly the individual passages that can and should be interpreted messianically, and he must state expressly that the passage speaks of the Messiah at that point. A necessary consequence of this reflection will eventually be that even in the translation, the systematic theory cannot be denied, namely that the content of one passage is transferred to another and one view is combined with another – all things that one searches for in vain in the translation of the LXX. Once (in Balaam’s blessing, Num. 24:7), it is indeed said differently from the original text: “A man shall come out of Jacob’s seed and he shall rule over many peoples.” But it is not only not said that this man is the Messiah, it is rather clear that it is to be a man, that is, a future king in general, who (v.17) will wound the princes of Moab and plunder the children of Seth.

394

The Isaiah prophecy

Continue reading “Bruno Bauer: Messianic Expectations of the Jews at the Time of Jesus”