I am copying here a post I just submitted on another forum, so with apologies to readers who have already seen this . . . .

This topic is not about “Jewish prophecies of the messiah’s arrival”. It is not about the second century Bar Kochba rebellion. Nor is it even about popular beliefs and attitudes at the time of the 66-73 CE Jewish war.

It is about the historical evidence we have or don’t have (that is the question) for:

- widespread/popular expectations

- of the appearance of a messiah figure to liberate Judea from Rome

- in the early years of the first century, let’s say up to around year 30 CE

I often read and hear scholars and lay people alike saying that Palestine or the Jews generally were strongly anticipating a messianic figure to appear around the time when, lo and behold, Jesus happened to appear. This is so often said in a way that assumes it is a well-known and indisputable fact of history. But some years ago when I started looking for the evidence supporting this claim (I fully expected to find plenty) I found the task was not so easy. What was cited as evidence so often appeared to me to be vague, imprecise, ambiguous at best and very often simply not relevant — not the sort of data that historians usually like to use as foundations for hypotheses.

I have since been reassured that I was not crazy or blind by discovering several reputable scholars who do say as much: that there is scant to no evidence for

- widespread/popular expectations

- of the appearance of a messiah figure to liberate Judea from Rome

- in the early years of the first century, let’s say up to around year 30 CE

I recently set out details of this [absence of] evidence in a series of blog posts responding to Richard Carrier’s arguments and supporting citations attempting to establish a popular messianic “movement” in early first century Palestine.

The details are covered in that series of posts but I will outline them here:

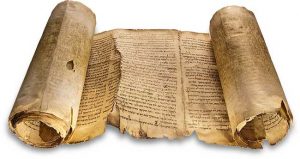

The Dead Sea Scrolls

Yes, there are messianic references found in some of these. But they are in fact very few compared with the total number of scrolls and surviving manuscript fragments. This relative “fewness” does not lead us to think that messianism was a particularly major preoccupation of the sectarians producing or using those scrolls (assuming “sectarians” of some sort were responsible for them).

Yes, there are messianic references found in some of these. But they are in fact very few compared with the total number of scrolls and surviving manuscript fragments. This relative “fewness” does not lead us to think that messianism was a particularly major preoccupation of the sectarians producing or using those scrolls (assuming “sectarians” of some sort were responsible for them).

Moreover, the messianic references that do exist do not, if I recall correctly, give any indication that a messiah was to appear “within a few years/generation” around the early first century (or any specific period). One could write of a doctrinal belief in a messianic future without being hung up about it and getting everyone around enthused to expect it to happen “any day now”.

Besides, one has to ask the extent to which the contents of the DSS throw a light on the beliefs and attitudes of the more general illiterate population.

Other Second Temple writings

The main criticisms — especially relative fewness of the references, and their generalised (nonspecific) character — raised re the DSS also apply here.

Often these writings speak of God himself directly acting in some future day of judgment. We are so accustomed to think of God doing this through a messiah that we sometimes read a messianic figure into these passages. But like the OT books, most prophecies about the “last days” do speak of God directly acting in the world and make no mention of a messianic intermediary.

Besides, is it not a giant leap to impute to the illiterate population at large certain emotional or psychological attitudes towards passages in these texts that attract our attention?

Were not those who read, studied and discussed such texts just a tiny fraction of a percent of a tiny fraction of a percent of the entire population?

The OT books

Much the same criticisms as above apply here, too.

As significant background reading I can also recommend Matthew Novenson’s Christ Among the Messiahs. I have blogged a series on this book. The first two posts in that series address the problem of modern readers bringing their own ideological conceptions of “messiah” into their reading of the Biblical texts. Novenson points out how very often our concepts of the messiah are read into passages that would otherwise have no messianic associations at all. He further points out that our understanding of messiah derives from a period AFTER the Second Temple era and was not, at least according to the evidence we have, part of general Second Temple thinking.

In my first blog post I cover a wide range and history of scholarly views on the question. Novenson concludes that scholars assume Paul was countering a popular Davidic-conquering messiah notion of the Jews with his concept of Christ, but he finds no evidence in Paul that that’s what he was doing at all.

At the present time, scholarly scholarly opinion on χριστός in Paul is an ironic position. While most of the major monographs, commentaries, and theologies of Paul now follow Davies and Sanders in reading Paul in primarily “Jewish” rather than “Hellenistic” terms, on the question of the meaning of χριστός they nevertheless perpetuate the old religionsgeschichtliche thesis that Paul is revising, transcending, or otherwise moving beyond the messianic faith of the earliest Jesus movement.

Novenson also remarks:

Since the last sixty years in Jewish studies have witnessed a dramatic breakdown in consensus about what messiah Christology would look like and indeed whether it existed at all in the first century C.E. (my emphasis)

In my second blog post I cover

- what the popular messianic idea looks like — its various facets

- how that idea compares with text of the OT

- the OT passages most commonly cited by Second Temple writings as information about the messiah

But in none of this is there any indication what the mainstream illiterate population thought about any of these ideas — or even that they had the slightest idea that anyone was pondering them. Paul, in fact, can be interpreted as evidence that there was no messianic movement (apart from his own) in his time.

Josephus and Roman historians

Josephus speaks of an ambiguous prophecy that supposedly animated many rebels during the War. But we have no idea where that prophecy comes from or any indication that it had anything to do with a “messiah” figure. In the same breath he mentions another prophecy from the same source that clearly does not come from our OT writings:

Now if any one consider these things, he will find that God takes care of mankind, and by all ways possible foreshows to our race what is for their preservation; but that men perish by those miseries which they madly and voluntarily bring upon themselves;

for the Jews, by demolishing the tower of Antonia, had made their temple four-square, while at the same time they had it written in their sacred oracles, “That then should their city be taken, as well as their holy house, when once their temple should become four-square.”

But now, what did the most elevate them in undertaking this war, was an ambiguous oracle that was also found in their sacred writings, how,” about that time, one from their country should become governor of the habitable earth.” The Jews took this prediction to belong to themselves in particular, and many of the wise men were thereby deceived in their determination. Now this oracle certainly denoted the government of Vespasian, who was appointed emperor in Judea.

However, it is not possible for men to avoid fate, although they see it beforehand. But these men interpreted some of these signals according to their own pleasure, and some of them they utterly despised, until their madness was demonstrated, both by the taking of their city and their own destruction.

Historians have also noted that Josephus had a very strong motivation for making much more of this prophecy than may have been the historical reality. The prophecy served the political interests of an emperor who rose from “lesser social ranks”, Vespasian. Other historians of his day repeated it, thus indicating that Vespasian found it very useful to propagate in an effort to legitimize his rule. Josephus’s life was saved by it, too. So we have ample evidence to detect the political and personal functions of this prophecy, and reason to expect Josephus to make it much more of a “thing” than it was at its source — whatever that was.

But here we so often find modern “messianic biases” interfering with our reading. Here some warnings from William Scott Green are useful:

The major studies [of the messiah at the turn of the Christian era] have sought to trace the development and transformations of putative messianic belief through an incredible and nearly comprehensive array of ancient literary sources – from its alleged genesis in the Hebrew Bible through the New Testament, rabbinic literature, and beyond – as if all these writings were segments of a linear continuum and were properly comparable. Such work evidently aims to shape a chronological string of supposed messianic references into a plot for a story whose ending is already known; it is a kind of sophisticated proof-texting. This diegetical approach to the question embeds the sources in the context of a hypothetical religion that is fully represented in none of them. It thus privileges what the texts do not say over what they do say.

. . . .

The term “messiah” has scant and inconsistent use in early Jewish texts. Most of the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Pseudepigrapha, and the entire Apocrypha, contain no reference to “the messiah.” Moreover, a messiah is neither essential to the apocalyptic genre nor a prominent feature of ancient apocalyptic writings.

Then after summing up various scholarly arguments used to “prove” the existence of popular messianism in the time of Jesus:

These arguments, which are representative of a type, appear to suggest that the best way to learn about the messiah in ancient Judaism is to study texts in which there is none.

So we come to those other supposed “messianic pretenders” Josephus describes — Theudas, the Egyptian and many others from BC to CE.In response I can only point to Green’s warnings above. Not once does Josephus indicate any messianic associations with any of these. Bandit kings were surely not seen as “long awaited messiahs”. Some of the figures (Theudas, the Egyptian, for instance) were in fact acting out prophetic roles, not messianic ones. They imitated prophets of old. And Josephus and plenty to say about false prophets.

It is often said Josephus did not write about “false messiahs” because he didn’t want to “mention the war” to his Roman audience. That argument is surely very shallow given the way he is quite capable of identifying all sorts of false leaders, false prophets…. why not join in with this supposed Roman hate for messianism by making equal time to blast the “false messiahs” just as viciously? We would in fact expect him to do just that had he been aware of “false” messianic movements.

The Problem

Such, in outline, are the flaws that I see in the evidence that is usually cited to claim that early first century Palestine was experiencing a wave of messianic fervour.

The evidence for such a social phenomenon at that time and place simply does not exist. The data that is said to be that evidence is, I submit, only testimony to such a movement if we read our preconceptions into Josephus and other writings.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Worthy work. Thumbs up.

But if there was not a messianic hope, then precisely what does this imply?

Whas the Christ figure more connected with a spiritual, esoterical hope than in a military public hope?

I think for example about the mention of Christ in the pre-christian Odes of Salomon.

It seems that the spectrum of the possible implications are not so evident (like for example to say that the Essenes never existed: who can say what it implies?).

“Were not those who read, studied and discussed such texts just a tiny fraction of a percent of a tiny fraction of a percent of the entire population?”

Yes, just like today’s Bible scholars are a tiny percentile whose views rarely, if ever, reflect popular religious ideas.

But it sounds more dramatic to imagine a large “messianic movement” at work, rather than the private fantasies of a couple of ascetics in a cell.

If anyone was hoping Some Guy was going to show up and save them, that person is indistinguishable from God, hence the whole idea of Jesus as God-man. In the context of the Jewish revolt, it’s really unlikely that in anyone’s mind any individual man was going to show up out of thin air and suddenly make any difference against the Romans.

As Blood suggests, in the final stages and aftermath, desperation and hopelessness may have triggered such fantasies in the more committed in-denial individuals, but they would not have been widely published. This tells us yet again that Christianity was insignificant until after that war was over and desperate people could be preyed upon in the traditional Christian way.

Psychologically, people then were not different than people now. People became religious for pretty much the same reason: exploitation of fear, desperation and hopelessness especially those who were abandoned by their family. Jews who gave up and left Palestine must have seemed like traitors to Israelite nationalists. Christianity is still energized by some weird outsider version of Israel nationalism.

It would probably make sense that most Jews wouldn’t be waiting for or expecting a messiah.

If they believed what their scripture said then they believed that god simply acted whenever & whereever he wanted to. Oh occassionally he sent an anget/messenger but all of these were clearly not human unless they were pretending to be for a short time (the whole Sodom thing).

If they didn’t believe what their scripture said or if they at least didn’t take it literally they had even less reason to expect a messiah. All those Jesus ‘prophesies’ hadn’t been retroconned yet.

I’m failing to see your point with these recurring eruptions on messiahs/not-messiahs Neil. What does this bear on and how? In Josephos you have several men attempting magical re-enactments of parts of the Joshua conquest legend and roping in hundreds or thousands of the illiterate populace to follow them, and the denouement is their massacre by the Roman military – who clearly didn’t find this behaviour innocuous. If it quacks, waddles, and swims like a duck I’ll hazard it is a duck, tah very much.

Aside from sporadic mentions of messiahs understood in this fashion scattered across most of the surviving Second Temple literature no one is writing about messiahs understood in this fashion, so what? I don’t see anyone arguing this was a majority pass time but clearly it was being done or those sporadic, scattered mentions wouldn’t be there and hundreds and thousands of the illiterate masses wouldn’t be getting killed identifying with these ideas.

I can’t help but think you are indulging in the same hyper-specific inanities of definition the religious apologista use to rule their particular fetish as the real deal. I don’t know why you are doing it, particularly as this blog devotes umpteen pages of space to Roger Parvus and a thesis drawn from secondary and fantastic early Christian legend mongering that is at least a magnitude of dubious removed from Richard Carrier’s work.

Proving History/On the Historicity of Jesus is a formal statement and argument for a hypothesis; it is a beginning and not a final theory. Parts of it will turn out to some degree to be wrong. This is something Dr Carrier has emphasised and repeated on numerous occasions since beginning his research; nevermind it’s publication. Something else he has done repeatedly is ask that folk engage his argument; not some strawman of it. He has defined what he means by messiah, the Josephos instances meet his definition; you appear to be shooting down some other definition, either of someone else or that you have made up for yourself. Perhaps I have just failed to understand your argument but your point is lost on me.

cf. http://vridar.org/2016/08/02/questioning-carrier-and-the-conventional-wisdom-on-messianic-expectations/ncf

I’m interested in understanding the history of Christian origins. I often read that the early first century was characterised by widespread messianic expectations. My interest in history leads me to check and understand the evidence underlying the reconstructions I read about in history books. My search for the evidence behind the very common claim of early first century messianic expectations has turned up zilch. When I discovered a significant number of scholars who specialise in this time and topic likewise disputed the claim of popular Jewish messianism at this time I was particularly interested and followed up their works.

Now when I see the claim repeated I think it is worthwhile pointing out that there are good grounds for dismissing it as a popular myth.

I don’t think you have read my posts. I have addressed this, along with what some mainstream scholarship also has to say about it.

It would be more useful if you addressed my specific arguments. You write as if you have not read my words, but as if you have only glanced at the headings.

Again it would help if you could quote or cite something specific that I have written so I know how to respond to what you “feel” about my motives and attitudes.

(By the way, I am also wondering how much of Roger Pavus’s posts you read. Your portrayal of them suggests you missed most of their content. Again, you convey the impression of someone who has merely glanced at a few headings and merely presumed to know what was written.)

I believe I have worked with Carrier’s argument and definitions honestly and accurately. If I had misrepresented him in any way I would expect Richard himself to be among the first to write a complaint. Please identify for me where I have set up a straw man of Carrier’s argument or misrepresented him in any way.

Does it offend you that I attempt to point to the circularity in the common argument that you repeat here? Or if not circularity, the way messianism is read into episodes that with a little reflection we see have more immediate explanations that concur with typical historical experience? Or do you find it offensive that reading messianism into events where it is otherwise absent originated as a support for Christian myth?