Hi. I’m back again, for better or for worse. Over the past few weeks I have immersed myself in reading but have finally come to a point where I need to pause and take stock. The book I have to blame for pulling me up and forcing me to stop and think afresh is König Herodes : der Mann und sein Werk by Abraham Schalit — published way back in 1969. (I don’t read German but thanks to new technologies I made short work of translating it.) Although Schalit does not address Christian origins his study of King Herod did open up for me a fresh historical perspective through which to re-interpret so much of the diverse material that makes up our earliest Christian sources.

I don’t read German, as I said, and I was of all possible ways alerted to König Herodes through my reading of an essay in another foreign language, modern Hebrew. This one was made available through an international library supply service supplemented by my text-reading and translation technologies: Levine, Israel L. “Magemoth Meshihioth Be-Sof Yemei Ha-Bayith Ha-Sheni (= Messianic Trends at the End of the Second Temple Period).” Messianism and Eschatology, edited by Zvi Baras, Zalman Shazar Centre for the Furtherance of the Study of Jewish History, 1983, pp. 135–52. Now that chapter is going to have to be converted into a new post here soon since I was slightly nonplussed to see it supporting another view I have expressed here, the view that there is little evidence to support the widespread “fact” that the Jewish rebellion of 66-70 CE against Rome was motivated by messianic hopes. That’s for another time.

The key idea in Schalit’s King Herod that has sent my mind into re-examining the question of Christian origins is the thesis that the Roman imperial idea, the ideology, if you will, propagated from the time of the first Roman emperor, Augustus, met with two responses among the Judeans:

- Judeans who identified themselves as necessarily separate from gentiles (think of circumcision, sabbaths, marriage restrictions) had nothing in common with the idea of a world united by the values and laws of Rome;

- Judeans who opposed the exclusivity of some of their brethren and were wide open to the idea of being a full part of a common humanity.

As for the first kind, the separatists, we see their views set out in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. Recall those stories of “men of God” tearing out — not their own hair, but the hair of those Judeans who married gentiles. Those were the lucky ones: Phineas plunged a spear through one racially mixed couple. Daniel refused to pray even in secret when threatened with being thrown into the lion’s den. Sabbath-keepers chose to die rather than protect themselves from an enemy army on the sabbath day. Most of us are familiar enough with the relevant stories from the Old Testament and related books.

That familiarity can perhaps cloud the full significance of a quite different view of God and humanity that is expressed in other places in the same canon. Think of the original authors and readers of stories of Ruth, of Jonah, of Job. Ruth, a gentile, married an Israelite and became the great-grandmother of King David. Job is “from the land of Uz” and he speaks to a God who in the narrative appears to have no particular relation to Israel about a question of justice common to all humanity. Jonah has to learn a lesson about God’s acceptance of gentiles who repent and become righteous without any notion of the Mosaic laws. Several Psalms, Ecclesiastes supposedly by Solomon, and the Wisdom of Sirach further present a universalist view of God and the human experience.

Surely we have two opposing viewpoints among these Jewish authors. The second view could well find itself at home among Hellenistic writings of philosophers. The significance of that word “Hellenistic” deserves to be pondered at this point. It refers to the cultural world that belonged to the mixing of Greek and barbarian in the wake of Alexander’s conquests of the Persian empire. The Stoic philosophy that believed in the unity of humanity could trace its roots back to Alexander’s companion Aristotle. The ideas of some Jews or Judeans were evidently at home in such a world. Others were not.

What struck me so strongly about Schalit’s Herod was that those same two viewpoints among Judeans were very much alive and uncomfortable with each other in the time we associate with Christian origins. Herod (ca 37 to 4 or 1 BCE) was an Idumean who sought acceptance as a Jew. He was also a client king of Rome who owed his life and kingship to Augustus. Though King of Judea he embraced wholeheartedly the imperial program of Augustus. At this point, we need to backtrack just a little. . .

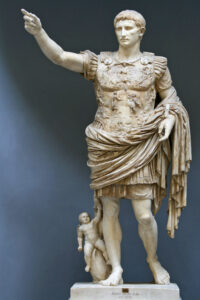

Augustus came to power as the final victor after a half-century of civil wars. His imperial propaganda machine went into overdrive. Augustus was the “saviour” and benefactor of “the inhabited earth”. Roman imperial rule was to become synonymous with “the good news” (it was a term of imperial propaganda) of peace, a restoration of “good old fashioned morality”, the spread of humanizing culture as expressed in the arts and literature and philosophy, and rule of law and justice for all. The Roman imperial idea took Alexander’s inheritance of uniting peoples under one divinely chosen ruler and magnified it beyond anything achieved by other successors. The Seleucid empire, for example, essentially took a “hands-off” approach towards subject peoples and let them do their own thing. Antiochus Epiphanes ran into trouble with religious zealots in Judea because he broke that tradition there.

You can probably see where I am headed with these ideas. Apologists have long posited that God prepared the world for Christianity in a way not very different from what I am proposing here — only without God and forethought.

Augustus could trust Herod to embody the full idea of the Roman civilizing mission and Herod did not fail him. Herod’s court attracted artists and intellectuals from other lands; his building program emulated the achievements in Rome itself; like Roman emperors he was the benefactor of the poor; he settled non-Jews in his Judean kingdom. But he could not have himself proclaimed as a god or even a demi-god as was the usual status of such leaders in his part of the world. He could, however, have his scribes fiddle with the genealogical records to show he was a descendant of David and hence — especially given his great accomplishments as king, expanding the borders and undertaking monumental building projects — potentially the promised Davidic Messiah. Unfortunately Herod had too many other faults to persuade enough others to that opinion. But even a powerful personality like Herod could not exist in an environment totally alien to everything he stood for.

The crucial point, it seems to me, is that Herod’s “Judaism” was in synch with that open or universalist idea we encounter in the books of Ruth, Jonah, Job, Ecclesiastes, Sirach etc. Herod failed to win the approval of the “legalists” and I cannot help but wonder if his failure was felt by others who were on his side with the more open kind of Second Temple religion.

There were evidently a significant number of Judeans who opposed their isolationist kin. And as evidenced by the Dead Sea Scrolls there were equally many Judeans who called down the judgment of God upon those of their kin who compromised with the Laws of Moses.

Now look again at our earliest Christian texts. Do not the gospels, certainly the Synoptic ones of Matthew, Mark and Luke, teach the highest values of the Greco-Roman culture? In case you’ve forgotten, have another quick look over

and

Recall the Stoic underlay throughout Paul’s epistles.

Recall the Gospel of Matthew opening up its account of Jesus by reminding readers of the sinners and gentiles — Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba — in Jesus’s ancestry.

Even recall the Roman imperial motifs in the gospels: The Gospel of Mark beginning with a line from Augustus’s propaganda about the “good news”; the imitation of emperor Vespasian’s miracles of healing the blind and lame; the inversion of the Roman Triumphal procession as Jesus is led to his crucifixion:

See also for further emperor-inversions in Jesus…

Recall, also, some of the earliest archaeological evidence we have for Christianity and how serene and “at home” it looks as if its creators were well-integrated members of society.

I have some sympathy for those who have attempted to locate Christianity’s origins in a Roman imperial conspiracy. But there is no evidence for such a hypothesis. There is even precious little evidence for the proposed motive behind such a conspiracy: a desire to pacify an unusually rebellious people by seducing the Jews into a religion of submission to Roman authority. The Jews were not particularly rebellious in comparison with others who chaffed at Roman rule. No, surely the initiative for a religious idea that did away with the exclusivist identity of many Judeans would have arisen among other Judeans of a different persuasion, of those who felt some embarrassment with their ethnic relatives.

How much more impetus must there have been for Judeans of that universalist mindset to present an “ecumenical” front to their pagan neighbours in the wake of the calamitous results of the Jewish wars in 70 and 135 CE.

Then recall how Jesus himself in the gospels is delineated as a fulfillment of all that can be described as the epitome of “Judaism”. I posted not long ago a lengthy series on one particular study that delves into the details of how the gospel Jesus is created out of so many texts and motifs of the Jewish Scriptures and Messianic viewpoints: Jésus-Christ, sublime figure de papier / Nanine Charbonnel

If some Judeans of the day did indeed attempt to sideline their “legalistic” family members by producing texts that unambiguously set the universalism of Ruth, Jonah, Sirach, and the rest front and foremost, they could not have done better than make a new successor to Moses, another Joshua, their focus. One might almost say that if Jesus had not existed it would have been necessary to invent him.

There is much more to add. One must, of course, account for persecutions and sectarianism in early Christian history. But the above is for now enough to set down the basis of initial thoughts on what might have led to the creation of Christianity.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“Now look again at our earliest Christian texts. Do not the gospels, certainly the Synoptic ones of Matthew, Mark and Luke, teach the highest values of the Greco-Roman culture?”

But are the Gospels our earliest Christian texts? Almost certainly not.

1st century Christ worship, if it was anything, was (1) essentially eschatological (1 Thessalonians, Revelation) and/or mystical (Gospel of Thomas, Odes of Solomon, early gnosticism, etc.); and (2) centered mainly in Asia Minor and Greece, where political concerns about Judeans and Romans would not have been a priority. I can see a case for a 2nd century transformation of the Christ cult for certain ideological (i.e. this-worldly) purposes in the writing of the Gospels and its story of a recent human messiah. But that takes us quite a ways from Herod and Augustus as real historical factors (as opposed to symbolic figures in the Gospels).

Looks like we had a similar reaction. :-]

Eschatology is a key point, as you note. It was necessary factor in the creation of a branch of Second Temple Judaism that was promoting an identity of a “new Israel” that was the fulfilment of Isaianic prophecies of gentiles joining with Israel to be united under one God. On another side of that theme, Stoics also understood that the cosmos was destined to end in a conflagration. 1 Thessalonians adds to this larger world view the importance of being moral exemplars to the world but not in the exclusivist sense of showing how different they were in terms of customs and rituals.

The Odes of Solomon have been understood as products of Hellenistic Jews, the kinds of Jews who stood apart from the legalists.

As for the setting of Asia Minor and Greece, these are the regions where we find some of the more liberal or Hellenistic Jews.

There were certainly transformations in Christian ideas over time and in different regions. I am not doubting that in any way.

I don’t mean to suggest that Herod and Augustus were actors in the origins of Christianity. My point about them was what they tell us about the ideas extant at those times.

https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/dspace/bitstream/handle/10161/3200/pdffinal.pdf On marriage and divorce in the diverse Herodian family.

Some of the universalists of the empire back then had their other son of god Caesar. Et tu Judas? Old Julius did say “Veni, Vedi, Vici” in Pontus where the Marcionites would later roam. Weren’t there some fringe mythicist books that said as much (or that Huller guy with his Marcus Agrippa messiah)?

Yeh. I’m not interested in any of those theories that posit some emperor or an Idumean or Judean king or tetrarch or whatever as a messiah. Maybe one day something will come along to change my mind on that but that’s not today.

Any opinion on this: https://www.academia.edu/13029752/An_alternative_essay_on_Jesus_Flavius_Josephus_the_Essenes_and_the_origins_of_Christianity It is a short synopsis of a book in French ‘Jesus – Un Mythe Aux Sources Multiples’ by a Stephan Hoebeeck

There was an article I recently skimmed but can’t find again now that Josephus came into possession of Luke or Luke-Acts because they were among his father’s papers being as they were addressed to him Theophilus [Mattathias ben Theophilus II]. A heavy burden of taxation over many years to support a small elite with little in return has more then once caused war.

All of the New Testament passages concerning alms and almsgiving, except one in Matthew, are in Luke-Acts. Therefore, these parables may be about alms, almsgiving and the proper use of the wealth controlled by the temple authorities. Luke’s criticism focuses on the use of these temple resources by the religious aristocracy for their own selfish purposes. This means that the religious authorities controlled tremendous wealth that had been in times past properly distributed to the people as part of the institutional form of almsgiving. The priests in these parables are unfaithful, dishonest and disobedient because, inter alia, they have not invited the poor, the maimed, the lame and the blind to the banquet table. Once the office of the High Priest became non-hereditary, and available to the highest bidder, the institutional role of almsgiving was abandoned or reduced as the purchaser had to recoup his purchase price.

I was introduced to Hoebeeck on another forum. I find the arguments too speculative for my liking. Apart from anything else, I think there are way too many hurdles to place the Gospels of Matthew and Luke in the first century.

Interesting concept that puts something of a twist on the question of origins.

What immediately popped into my mind were questions “Did the ‘original’ Christianity of Cephas, James and John come from this more liberal impulse or did Paul introduce those ideas into the nascent religion or was Christianity almost completely reinvented by Mark (using “Mark” as representing the first flowering of a new direction/emphasis)? So which is the origin of the religion?

The Qumran literature is of particular interest in the question of Christian origins given the overlaps of certain imagery used by the respective teams. I want to post about some of those overlaps — till then, I will simply note that there are several indicators that early Christians were reacting against the legalistic beliefs and practices that we find expressed in some of those scrolls. There were certainly debates and disagreements over what constituted the “correct religion”.

1. Judeans who identified themselves as necessarily separate from gentiles (think of circumcision, sabbaths, marriage restrictions) had nothing in common with the idea of a world united by the values and laws of Rome;

Judeans who opposed the exclusivity of some of their brethren and were wide open to the idea of being a full part of a common humanity

It seems to me that also when Christian writers fit the Judeans of the kind 2 above, the universalism was always declined in imperialistic (=subversive, anti-Roman) terms, more than showing mere anti-esclusivism.

Georgios Sidirountios appears to have listed all the evidence of anti-hellenism in the early Christian writings. It seems that the Greeks as distinct from the Romans, were particularly hated by early Christians. This explains why especially ethnically Greeks were the famous anti-Christian polemists, and the later efforts of apologists to hellenize Jesus.

If you really think the Gospels share some sort of commonality

with Emperor Augustus’ goals, what more is there to say ?

Plenty. Where were the commonalities? What purpose(s) did the author(s) attribute to the commonalities? What do commonalities suggest about the gospels’ origins and reliability?

re “there is little evidence to support the widespread “fact” that the Jewish rebellion of 66-70 CE against Rome was motivated by messianic hopes”

My understanding is the rebellion first started with a dispute (or two) much further north on the coast, between Jews and Samarians/Samaritans, and ongoing disputes and fighting between Jews and the Roman authorities (who had quelled the initial dispute/s) that gradually rolled further south and inland to eventually end up in the countryside around Jerusalem, and, while that caused new disputes among Jewish groups in and around Jerusalem, those new disputes were not b/c of ‘messianism’.

Indeed. When Josephus does introduce the idea that a prophecy of a world-ruling king from the east was soon to appear he does so “out of the blue”, so to speak — nothing in what he has written up until then prepares the reader for such a motivation.

Until then he at best cites some “false prophets” but none of these is a messianic figure and certainly those who were slaughtered unarmed clearly were offering no military effort to bring on the messiah’s appearance.

“The Gospel of Mark beginning with a line from Augustus’s propaganda about the “good news” …”

Yep, from the Priene Calendar Inscription, in which Augustus was called ‘a Saviour’ [sent by Providence]

Another key similarity is “the beginning of the ‘good news’ ” – In the inscription the verbal form is employed (άρχειν) while in Mark the nominal form is employed (άρχή).

Evans, Craig A. (2000) ‘Mark’s Incipit and the Priene Calendar Inscription: From Jewish Gospel to Greco-Roman Gospel’ Journal of Greco-Roman Christianity and Judaism 1: 67–81

Have we forgotten that so much of “Hellenistic Judaism” came from Egypt as well as Jewish communities (called “Jewish mercenaries) scattered all around the Roman Empire, many of whom were very “Literate”.

https://academic.oup.com/yale-scholarship-online/book/37391 back to the beginning in the foreign legion where they fought alongside Carian and Ionian mercenaries in service to the Saite Dynasty and then the Persians in Egypt.