Here we come to a dramatic turning point in the narrative (including a change of tense). Whose is the “great voice from Heaven” that calls out “Come up here”? We are not told. Even the phrase “spirit of life from God” does not mean that God raised up the two martyrs but only that it was God’s spirit that entered into them: the author uses a different expression when he wants to convey the idea of God directly acting. Who, exactly, “saw them” and reacted in fear is also left vague.

Readers who think the two witnesses are a kind of latter-day Moses figure run into the problem that there was no Jewish tradition — neither biblical nor in Josephus nor Philo — that Moses was bodily resurrected.

One would presume that the voice from heaven was God speaking but that interpretation is not certain. Revelation refers to other heavenly voices that do not belong to God.

It is also odd that we read nothing further here about the beast from the abyss that had just killed the two “witnesses” or “martyrs”. It is as if he is no longer at the scene to witness the sudden turn of events and the ascension to heaven.

One more oddity: only in this passage in Revelation do enemies of God give glory to God as a result of witnessing or experiencing calamitous events like an earthquake or plague or other catastrophe. In every other such scenario they respond with intensified anger.

Such are the difficulties that concern us but we must ask if they would also have troubled the original readers. Would the first audiences have understood exactly who and what was being described?

Sit back (or forward if you prefer to concentrate) and observe the following case for Revelation‘s two witnesses being an adaptation of another Jewish source document. And prepare to meet a new character in one of the stories, the virgin Tabitha who gruesomely has her blood sucked from her.

After this journey we will return to the above resurrection and ascension passage and examine it afresh.

Analysis of Revelation 11:3-13

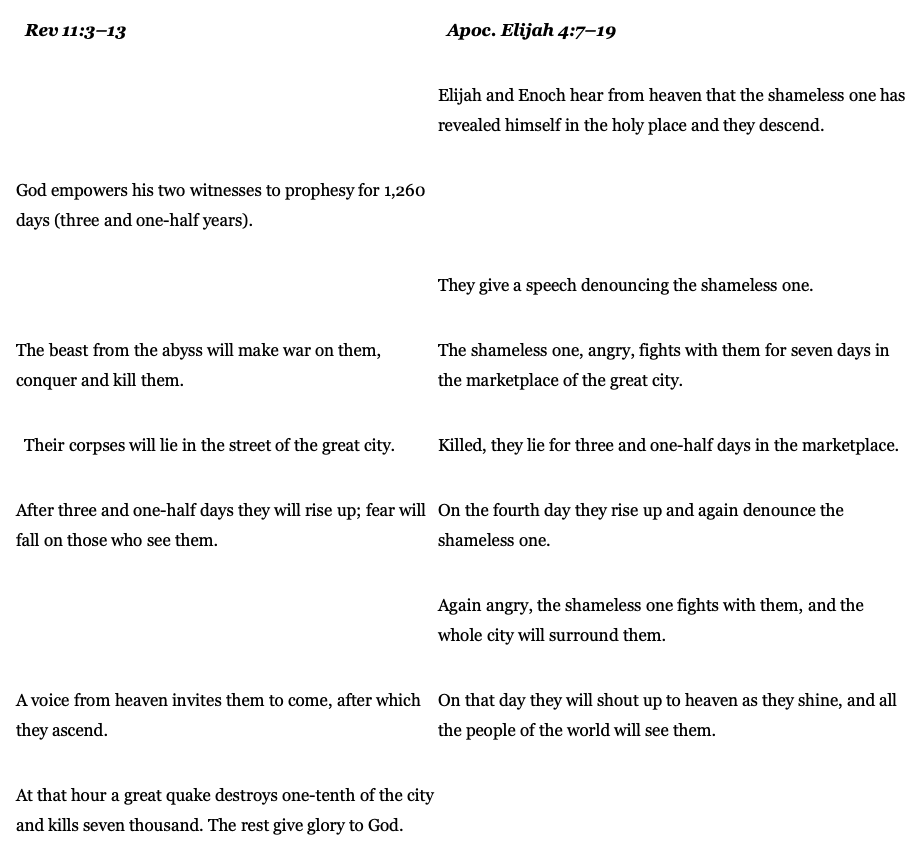

The first question Thomas Witulski [W] explores is whether the author was creating a new narrative entirely from his imagination or whether he was re-working a “tradition” known to him. To answer that question W compares 11:3-13 with two similar accounts: the Apocalypse of Elijah and a chapter by the church father Lactantius in Divine Institutes. Can these works be shown to depend on Revelation 11 or do they indicate the existence of an earlier account that we can say was also available to the author of Revelation?

Apocalypse of Elijah (see the earlywritings site for views on date and provenance: W notes it belongs to the second half of the third century CE)

The relevant passage:

My blood [that is the blood of an earlier mentioned virgin named Tabitha] you have thrown on the temple has become the salvation of the people.

Then, when Elijah and Enoch hear that the Shameless One has appeared in the holy place, they will come down to fight against him, saying,

…

The Shameless One will hear and be furious, and he will fight with them in the market-place of the great city; and he will spend seven days fighting with them. And they will lie dead in the market-place for three and a half days; and all the people will see them. But on the fourth day they will arise and reproach him, saying

…

The Shameless One will hear and be furious and fight with them; and the whole city will gather round them. On that day they will shout aloud to heaven, shining like the stars, and all the people and the whole world will see them. The Son of Lawlessness will not prevail over them.

He will vent his fury on the land

…

(From The Apocryphal Old Testament edited by H.F.D. Sparks)

In both accounts:

- two end-time figures appear

- the enemy appears in Jerusalem

- prophets fight with him but he kills them

- their corpses lie in the market place 3 1/2 days

- they are resurrected and (the text is questionable in the Elijah apocalypse) ascend to heaven

So both texts clearly contain the same narrative core.

Differences that suggest to W (and other scholars) that there is a third source behind Revelation and the Apocalypse of Elijah:

- no names in Revelation; named prophets in the Apocalypse of Elijah (The Apocalypse of Elijah appears to be inspired by and continuing the tradition of apocryphal Jewish and early Christian writings about Elijah and Enoch — unlike Revelation‘s account.)

- a set time of prophetic activity is specified in one but not the other

- in the Apocalypse of Elijah the two prophets are not symbolized as representatives of Israel or Jewry in Palestine as we find in Revelation 11; and Jerusalem is not represented theologically in the Elijah Apocalypse as it is in Revelation 11:8

- The description of the power and authority and imagery of biblical dignity of the two figures that we find in Revelation 11:5f is absent from the Apocalypse of Elijah

- in the Apocalypse of Elijah the two prophets appear only at the end of the effective time of the “Shameless One” and confront him decisively on the spot (or within 7 days); in Revelation there is an ongoing battle of some years and a promise of eventual overthrow of existing political, social and societal conditions or arrival of God’s kingdom

- the attention of the world is captured by the two witnesses in Revelation; the audience within Apocalypse of Elijah is more local

- Revelation 11 describes the resurrection and ascension in considerably more detail than the Elijah Apocalypse

- Enoch and Elijah are said to rebuke the Lawless One after they are resurrected and their enemy takes up his fight anew after their ascension to heaven; but in Revelation there is no counterpart to any of that scenario: nothing is heard of the two witnesses after their ascension and we hear nothing more of the “beast” after that event

- the earthquake and response of the inhabitants in Revelation has no counterpart in the Apocalypse of Elijah

From the above similarities and differences W proposes (as do a number of other researchers such as Schräge and Aune) that the documents are based on an independent common tradition. D. E. Aune writes in his commentary on Revelation (bolding in all quotations is my own addition):

Though the Coptic Apocalypse of Elijah is of uncertain date (A.D. 150 to 275; see Wintermute in Charlesworth, OTP 1:729–30), in its present form, it is a Christian document that is probably a revision of an earlier Jewish composition that perhaps originated during the first century B.C. (Rosenstiehl, L’Apocalypse d’Elie, 75–76). It exists in Greek in one fragmentary text and two quotations (Denis, Fragmenta, 103–4). It is clear that Apoc. El. 4:7–19 is either dependent on Rev 11:3–13, or that both passages are dependent on an earlier source. For reasons that will be discussed below, the latter hypothesis appears the most likely (see Joachim Jeremias, TDNT 2:939–41). The parallels and differences are indicated in the following synoptic summaries:

Aune continues

The narrative begins with the two Israelite worthies in heaven, where they had been raptured according to OT and Jewish tradition, and they only make their appearance through a descent from heaven after they learn that the eschatological adversary has revealed himself in Jerusalem, presumably in the temple. Thus this text provides an explanation for the presence of the two witnesses, which is mysteriously left unaccounted for in Rev 11:3–13. Unlike in Rev 11:3–13, they are said to address the adversary (see the Tabitha account below). The conflict between the adversary and Enoch and Elijah lasts seven days, and when they are killed, their bodies lie for three and one-half days in the marketplace. As in Rev 11:11, they are resurrected (though the mention of the fourth day seems to presuppose that they were dead for three days in an earlier version). They again denounce the adversary in a speech (as in the Tabitha account below), and this time the adversary and the population of the city surround them, doubtless intending to do away with them again. They shout to heaven (unlike in Rev 11:12, where the two witnesses are addressed by a heavenly voice), implicitly for divine assistance. This assistance is apparently provided, for they take on a glorified shining appearance, and since all the people in the world can see them, they apparently ascend to heaven (cf. Rev 1:7, “every eye will see him”). Though there is a basic similarity between these two texts, the only clear instance of the dependence of Apoc. El. 4:7–19 on Rev 11:3–13 is Apoc. El. 4:13–14 (the Shameless One fights and kills Elijah and Enoch in the marketplace of the great city, where they lie dead for three and one-half days) on Rev 11:7–9 (the beast fights and kills the two witnesses, and their corpses lie on the street of the great city for three and one-half days). It is probable, however, that this similarity is based on a later Christian revision of an earlier Jewish source.

The relationship between the two texts is more complex, however, because of a doublet involving a woman named Tabitha in Apoc. El. 14:9–15:7, with italicized portions containing parallels to the noted texts (P. Chester Beatty 2018; tr. Pietersma, Apoc. El.):

The young woman whose name is Tabitha will hear that the shameless one has made his appearance in the holy places. She will dress in her linen clothes and hurry to Judaea and reprove him as far as Jerusalem, and say to him, “O you shameless one, O you lawless one, O you enemy of all the saints!” Then the shameless one will become angry with the young woman [Rev 12:17a].

He will pursue her to the region of the setting of the sun [Rev 12:6, 13–14].

He will suck her blood in the evening and toss her onto the temple, and she will become salvation for the people.

At dawn she will rise up alive and rebuke him saying, “You shameless one, You have no power over my soul, nor over my body, because I live in the Lord always, and even my blood which you spilled on the temple became salvation for the people.”

In this text, as in the following one from Lactantius, a single messenger from God is involved rather than two. In this case it is a woman named Tabitha. While the scenario is strikingly similar to Rev 11:3–13, the differences are such that there appears to be no literary relationship between the two texts. As in Rev 11:7, there is a single enemy, who is the eschatological adversary. This adversary appears in the “holy places,” i.e., “Jerusalem,” and Tabitha dons a special linen garment (suggesting purity and priesthood) and meets the adversary. Unlike Rev 11:3–13, but similar to Apoc. El. 4:8–12, Tabitha reproves the adversary with a brief speech, which angers him (note the parallel to Rev 12:17). He pursues her to the east (again cf. Rev 12:6, 13–14) and kills her and (using the vampire motif) sucks her blood. That he is suddenly back in Jerusalem with her body suggests that the italicized portions in the translation above have been interpolated into an earlier text. After she has been thrown onto the temple, she will rise from the dead the next morning (an interval of one day, not three or three and one-half days) and again reprove the adversary with a brief speech to the effect that throwing her on the temple has provided salvation for the people, a motif drawn from Jewish martyrological literature. Further, nothing is said about an ascension to heaven.

(Dr. David Aune. Revelation 6-16, Volume 52B (Kindle Locations 10593-10649). Zondervan. Kindle Edition.)

W gives the following reasons for concluding that the author of Revelation is using a Jewish narrative now lost to us:

- the account of the two witnesses in Rev 11:3-13 can be easily read as principally a Jewish narrative (remove only the reference to “where [the] Lord was crucified”)

- certain details in Rev 11:3-13 stand in stark contrast to what we know of early Jewish tradition (cf the deadly violence of the prophets)

- in numerous early Christian writings we can trace a tradition independent of Rev 11 yet having both similarities to Rev and also suggestions of Jewish provenance

Lactantius in Divine Institutes (ca 300 CE)

Impatient readers can skip this section if they want to dwell only on W’s own ideas. W will conclude that Lactantius is using and modifying Revelation 11:3-13, unlike the author of the Apocalypse of Elijah that is using a source that also lies behind Revelation 11.

When the close of the times draws near, a great prophet shall be sent from God to turn men to the knowledge of God, and he shall receive the power of doing wonderful things. Wherever men shall not hear him, he will shut up the heaven, and cause it to withhold its rains; he will turn their water into blood, and torment them with thirst and hunger; and if any one shall endeavour to injure him, fire shall come forth out of his mouth, and shall burn that man. By these prodigies and powers he shall turn many to the worship of God; and when his works shall be accomplished, another king shall arise out of Syria, born from an evil spirit, the overthrower and destroyer of the human race, who shall destroy that which is left by the former evil, together with himself. He shall fight against the prophet of God, and shall overcome, and slay him, and shall allow him to lie unburied; but after the third day he shall come to life again; and while all look on and wonder, he shall be caught up into heaven. (7:17, 1-3)

The similarities with Revelation 11:

- end time prophet

- with authority and power to punish

- name unmentioned

- preaching (though the content of the message is not noted in Revelation)

- at end of his mission an end-time adversary appears to kill him

- resurrected after three days and ascends to heaven

- bystanders are amazed

The differences:

- one prophet versus two

- the one prophet is said to preach repentance and conversion — no content of the message in Rev 11

- the single prophet is not depicted in biblical terms from Zechariah (olive trees, lampstands) but only said to be a “great prophet”

- the enemy king is specified as from Syria with an “evil spirit”, unlike the “beast from the abyss” in Rev 11

- Lactantius’s account gives no geographic setting

- the reaction of the onlookers to the death and resurrection is not given by Lactantius

- Lactantius lacks the detail we read in Rev 11 on the resurrection and ascension

- no reference by Lactantius to the universal audience of the events, nor of an earthquake and repentance of onlookers

W refers to another observation by Aune, and it is only fair that I give Aune’s view that differs from that of W:

Lactantius Div. Inst. 7.17 exhibits close parallels with Rev 11:3–13 (see the discussion in K. Berger, Auferstehung, 66–74; Flusser, “Hystaspes,” 12–75). . . .

But there are, in fact, several reasons for supposing that Lactantius is dependent here on the Oracles of Hystaspes or some Jewish source and not on Rev 11:3–13, based on similarities and differences between these two texts.

(1) A single prophet is found in Lactantius (who probably is dependent on an Elijah tradition); two prophets are found in Revelation.

(2) The result of closing the heavens and turning the waters into blood in Lactantius is to torment people with hunger and thirst, while this effect is absent from Revelation.

(3) The narrative in Revelation is consistently told with verbs in past tenses, while that in Lactantius is told using future tenses. [W draws attention to this point noting that it “requires an explanation”]

(4) The text in Revelation contains a number of explanatory glosses . . . , none of which appear in the account of Lactantius.

(5) The narrative in Lactantius continues on to describe events similar to those in Rev 13:1–10 . . . , but with no apparent allusions to Rev 11:14—12:17.

(6) The concluding earthquake that destroys one-tenth of the city, kills seven thousand people, and results in the mass conversion of survivors in Rev 11:13 is not mentioned in Lactantius, which suggests that this element has been added by John.

(7) There is no mention in Lactantius of the variations on three and one-half found in Rev 11:3, 9, 11, namely 1,260 days (v 3) and three and one-half days (vv 9, 11), which also suggests that these have been added by John.

(8) There is no mention in Lactantius of the city or its inhabitants, though these elements are essential for Rev 11:3–13 (K. Berger, Auferstehung, 71).

(9) The identification of the enemies of the two witnesses as two separate entities, the beast and the representatives of all nations found in Rev 11:3–13, is missing in Lactantius.

(10) The preliminary successes of the witness in converting his hearers has no parallel in Rev 11:3–13.

(11) Lactantius places this event “when the end of these times is imminent,” while there is no explicit link with the eschaton in Rev 11:3–13.

(Dr. David Aune. Revelation 6-16, Volume 52B (Kindle Locations 10650-10714). Zondervan. Kindle Edition. My formatting)

W thinks Lactantius is indebted to Revelation rather than another (Jewish) tradition because of the closeness of their structures and contents.

Witulski’s conclusion

Revelation 11:3-13 has, like the Apocalypse of Elijah, processed a Jewish tradition. However, Revelation 11 has hewed more closely to the original tradition than has the Apoc Elijah. A comparison between the two ways this tradition has been handled can give important clues to the intentions behind the account of the two witnesses in Revelation.

How Revelation reworks the tradition

So what is unique to Revelation 11:3-13? W turns to two works of Klaus Berger to assist in this part of the discussion.

a. The first distinctive point to note about Revelation‘s two witnesses is that they are presented as earthly figures who need to have their power and authority given to them from an outside source. Contrast Apoc Elijah where Enoch and Elijah are heavenly figures who have their power and authority inherent in themselves.

b. The time limitation (of 1260 days) that is assigned for the work of the two witnesses in Rev 11 is another distinctive point.

c. Revelation 11 alone presents the end-time prophets as political and priestly leaders of Israel or Palestinian Jewry. If the author of Rev 11:4 chose to draw upon Zechariah’s imagery to describe his two witnesses then we have an important clue for interpreting the contemporary identity of these two figures.

d. The anonymity of the two witnesses is another significant unique feature in TW’s view. In the vast majority of Jewish and early Christian parallels to Revelation 11:3-13 the two witnesses are identified. In the Apoc Elijah we obviously see them as Elijah and Enoch. W suggests that by anonymizing these two and their opponent the author is detaching them from known tradition to enable a reinterpretation that applies to contemporary persons.

e. Apart from Lactantius (which W believes is a re-written version of Rev 11) the details of the horrendous plagues that the two witnesses inflict on their enemies and the natural consequence of great joy at their deaths is unique in all parallel traditions.

f. Revelation‘s contextualizing the narrative of the two witnesses globally, so that all tribes and tongues and peoples are affected by their activity and final deaths, is another distinctive point. The two witnesses do not play out in a drama that is known to only a small corner of the world.

g. That the beast or enemy of the prophets appears to make war and kill them at the end of their testimony is another largely singular feature.

h. No other comparable tradition depicts Jerusalem as Sodom and Egypt and the place where [the] Lord was crucified.

i. Unlike the comparable accounts is Revelation‘s ending of the activity of the witnesses after their resurrection and ascension. In other works the ascended prophet(s) continue to taunt their enemy. Revelation stands out from parallels by including graphic descriptions of how onlookers responded to the resurrection and ascension.

j. Another significant detail is that in Revelation alone such witnesses are clearly linked to the temple.

Consequences for interpretation

Why did our apocalyptist make such changes to the traditional account? Was it purely for the sake of creativity or for some theological reason? If so, then how are we to explain why he left the two witnesses unnamed? Why did he associate them with biblical imagery pointing to political and priestly leadership of Israel? Why did he extend their role to a world-wide stage and audience?

To translate W:

On the other hand, it makes much more sense and leads further to look for the reasons for the apocalyptist’s treatment of the tradition in this way in his local or contemporary historical context. With Rev 11:3-13 and the remarks in these verses, the author of the last book of the New Testament canon refers to concrete persons, events and previous circumstances that occurred in the time, or more precisely, quite immediately before the time of the writing of the Apocalypse and are known to both him and his addressees.

The very idea of a conscious local or contemporary historical recontextualisation of the tradition handed down makes it understandable why the apocalyptist in Rev 11:3ff. has worked on the underlying tradition so extensively and comprehensively. (p. 123 – my formatting)

By removing names from the two prophets of tradition the author allows his readers to search for a new interpretation of a familiar narrative. Leaving them unnamed almost compels his readers to find new identities and it would be natural to seek them in terms of contemporary and local events.

Look again at the significant changes the apocalyptist made for his readers:

— The two witnesses are associated with biblical imagery representing the political and priestly leadership of Israel; that is, they were not timeless figures, ciphers for prophets. They were associated specifically with Jerusalem. They did not come down from heaven as the prophets of the tradition did. These two witnesses were earthly figures, secular and spiritual leaders in the region of Jerusalem. These details are highly significant since we have seen above how other Christian authors of comparable works, who also knew of Revelation and Zechariah, chose to drop those particular motifs.

— The apocalyptist’s labelling of the enemy as the beast rising out of the abyss links him to the beast of Revelation 13, that is, to the beast who was venerated as divine by the whole world. We have seen reasons for interpreting this beast as Hadrian, the same emperor who was causing the churches in Asia so much grief. Such a description — “beast ascending from the abyss” — is a unique contribution to the traditional material and his role in slaying the two witnesses is surely another key to their identities.

— The characterization of Jerusalem as Sodom and Egypt might well be understood as an indication that at the time of writing Jerusalem was no longer a Torah-lit city of David worshiping the Jewish god but a place of pagan worship and practices.

— That the two witnesses in Revelation defy the comparable tradition and narratives (with the exception of Lactantius) by waging violence against their enemies, and even for a time can hold their own against their opponents, is another indicator that they represent historical figures contemporary with or immediately prior to the writing of Revelation.

In the next post we’ll look at further indicators that Revelation 11:3-13 is the reworking of another document. We will also cover the integrity of the passsage as a whole and see if any part of it is out of place and an alien intrusion.

Aune, David E. Revelation 6-16. EPub. Word Biblical Commentary, Volume 52B. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan Academic, 2017.

Sparks, H. F. D., ed. The Apocryphal Old Testament. Oxford : New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Witulski, Thomas. Apk 11 und der Bar Kokhba-Aufstand : eine zeitgeschichtliche Interpretation. Tübingen : Mohr Siebeck, 2012. http://archive.org/details/apk11undderbarko0000witu.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

One thought on “The Two Witnesses of Revelation 11 – part C”