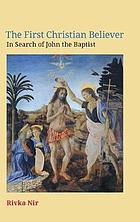

I have been sidetracked from blogging regularly for a while now so I’m long overdue for continuing Rivka Nir’s case (The First Christian Believer: In Search of John the Baptist) for the John the Baptist passage in Josephus being a Christian interpolation. Previous posts are

- John the Baptist Resources

- John the Baptist: Another Case for Forgery in Josephus

- Early Thoughts on Authenticity of the John the Baptist Passage in Josephus

Now I have to confess my exploration of John the Baptist since last year has been the result of following up Gregory Doudna’s chapter in a festschrift for Thomas L. Thompson. So far I have not posted in depth on Greg’s views but the summaries I have set out with links to the chapter online have generated some discussion: see

- Interpolations in Josephus’s Antiquities of the Jews

- continuing … Biblical Narratives, Archaeology, Historicity – Essays in Honour of Thomas L. Thompson

- Another Pointer Towards a Late Date for the Gospel of Mark?

In this post the specific point made will serve both Nir’s and Doudna’s views. Nir argues for Christian interpolation; Doudna for a misplaced Josephan passage.

Nir points to James H. Charlesworth’s criteria for identifying interpolations in apocryphal writings. Criteria #2 and #3 would just as easily point to a misplaced passage as a foreign interpolation:

- (2) if the passage is not integrated into the context syntactically;

- (3) if the passage is easily removable and upon its removal the text’s sequence becomes clear.

Nir adds another but its relevance applies to examining the passage from a perspective that does not concern us in this post. Here we look at how the passage fits syntactically.

Rivka Nir directs our attention to the thought immediately preceding and then immediately following the John the Baptist passage as earlier addressed by Léon Herrmann — and noted by others, too, as we have seen in several posts over the years. It’s not a new observation but I think it is worth setting it down here again for reference.

Immediately before the JB passage (paragraph 115):

So Herod wrote about these affairs to Tiberius, who being very angry at the attempt made by Aretas, wrote to Vitellius to make war upon him, and either to take him alive, and bring him to him in bonds, or to kill him, and send him his head. This was the charge that Tiberius [καὶ Τιβέριος μὲν] gave to the president of Syria.

and immediately following (paragraph 120) the JB passage:

So [δὲ] Vitellius prepared to make war with Aretas, having with him two legions of armed men; he also took with him all those of light armature, and of the horsemen which belonged to them, and were drawn out of those kingdoms which were under the Romans, and made haste for Petra, and came to Ptolemais.

Nir’s comment:

On removal of the passage, paragraph 120 flows smoothly and uninterruptedly from paragraph 115 and the order of events and correct syntactical structure are retained: Tiberius commands and Vitellius acts. (Nir, p. 44)

Nir adds another point,

Furthermore, Josephus had already explained how ‘all Herod’s army was destroyed by the treachery of some fugitives, who, though they were of the tetrarchy of Philip, joined with Aretas’s army’ (Ant. 114), his seemingly historical explanation for Herod’s defeat which is placed in the appropriate context. Why, then, would Josephus need to provide an additional explanation? And why place it at a distance from his first explanation, and moreover in a way that interrupts the factual sequence?

It may be worth adding another detail Nir references, one made by John P. Meier in volume 2 of A Marginal Jew (pp. 59f): The JB passage can be read as an inclusio, as a self-contained capsule.

Now some of the Jews thought that the destruction of Herod’s army came from God, and that very justly, as a punishment of what he did against John, that was called the Baptist: for Herod slew him, who was a good man, and commanded the Jews to exercise virtue, both as to righteousness towards one another, and piety towards God, and so to come to baptism; for that the washing [with water] would be acceptable to him, if they made use of it, not in order to the putting away [or the remission] of some sins [only], but for the purification of the body; supposing still that the soul was thoroughly purified beforehand by righteousness. Now when [many] others came in crowds about him, for they were very greatly moved [or pleased] by hearing his words, Herod, who feared lest the great influence John had over the people might put it into his power and inclination to raise a rebellion, (for they seemed ready to do any thing he should advise,) thought it best, by putting him to death, to prevent any mischief he might cause, and not bring himself into difficulties, by sparing a man who might make him repent of it when it would be too late. Accordingly he was sent a prisoner, out of Herod’s suspicious temper, to Macherus, the castle I before mentioned, and was there put to death. Now the Jews had an opinion that the destruction of this army was sent as a punishment upon Herod, and a mark of God’s displeasure to him.

The bolded opening and closing words contain the same concepts:

- the Jews

- opinion/thought

- destruction of Herod’s army

- divine punishment

- justly deserved

- John executed

None of the above (except arguably for Nir’s added “another point”) is inconsistent with Greg Doudna’s view, as I understand it. We will see different interpretations enter with further discussion. What the above does suggest, however, is that the John the Baptist passage as understood by readers in the Christian tradition was not original to the book 18 of Antiquities.

Nir, Rivka. First Christian Believer: In Search of John the Baptist. Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2019.

Meier, John P. A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus. V. 2. Mentor, Message, and Miracles. New York: Doubleday, 1994.