A new article appearing in the peer-reviewed Digital Scholarship in the Humanities: An Application of a Profile-Based Method for Authorship Verification: Investigating the Authenticity of Pliny the Younger’s Letter to Trajan Concerning the Christians. Author: Enrico Tuccinardi.

A new article appearing in the peer-reviewed Digital Scholarship in the Humanities: An Application of a Profile-Based Method for Authorship Verification: Investigating the Authenticity of Pliny the Younger’s Letter to Trajan Concerning the Christians. Author: Enrico Tuccinardi.

Book 10 of Pliny the Younger‘s letters consist of his correspondence with the emperor Trajan when he was governor of Bithynia/Pontus. Letters 96 and 97 are the famous exchange over the question of what to do about the Christians. These letters are the earliest evidence for Christianity found outside Christian sources and after the controversial references in Josephus.

The article with its bibliography have introduced me to recent developments in various techniques of author attribution studies. I’ll explain some of the details later, but to begin with I’ll set out an overview of how Tuccinardi studied the style of the Pliny’s famous letter against the rest of his letters to Trajan.

First, though, here is the abstract:

Pliny the Younger’s letter to Trajan regarding the Christians is a crucial subject for the studies on early Christianity. A serious quarrel among scholars concerning its genuineness arose between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th; per contra, Plinian authorship has not been seriously questioned in the last few decades. After analysing various kinds of internal and external evidence in favour of and against the authenticity of the letter, a modern stylometric method is applied in order to examine whether internal linguistic evidence allows one to definitely settle the debate. The findings of this analysis tend to contradict received opinion among modern scholars, affirming the authenticity of Pliny’s letter, and suggest instead the presence of large amounts of interpolation inside the text of the letter, since its stylistic behaviour appears highly different from that of the rest of Book X.

I’ve read some of those early debates and the article by Sherwin-White that seems to have settled the argument in favour of the authenticity of Pliny’s letter 10.96, and although a few doubts have never completely vanished, I have decided it wisest to accept the letter as genuine, at least for the sake of argument, pending any new evidence that might surface.

In brief, what Tuccinardi has shown is that a stylometric analysis of Pliny’s letter about the Christians is as stylistically different from the remainder of Pliny’s letters to Trajan as are letters of Cicero and Seneca.

The analysis

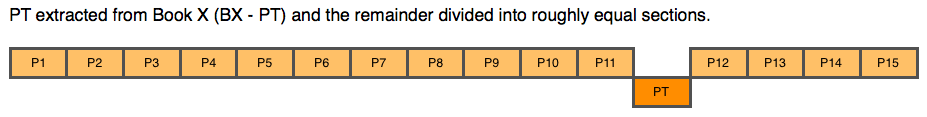

The letters of Pliny in Book 10 were isolated from Trajan’s and other correspondence. Pliny’s letter 96 (called the PT — the Plinian Testimonium) was separated from the others. The text of the remainder of Pliny’s letters was divided up into fifteen sections about the same length as the PT. That is, about 3000 characters each.

The stylometric analysis of each one of these fifteen fragments was then compared, in turn, with the remainder of the Pliny set. Finally, the PT was compared to see if was as close or as different in its comparison with the main body as were each of the other fifteen sections. If you prefer visuals to words here is Tuccinardi’s diagram to clarify the process. Lk is the text of known authorship, and Lu is the section of disputed or proxy disputed or unknown text:

The method is based on the idea that every author has a stylistic “fingerprint” that is subconscious and hence unable to be normally recognized by readers, and hence unable to be hidden or copied. Of course there is another level at which authors do consciously work on their style and even imitate others sometimes, but what is identified by the stylometric analysis here is a unique authorial profile that works at a yet deeper and unselfconscious level.

Character Features

According to this family of measures, a text is viewed as a mere sequence of characters. That way, various character-level measures can be defined, including alphabetic characters count, digit characters count, uppercase and lowercase characters count, letter frequencies, punctuation marks count, and so on. (de Vel et al., 2001; Zheng et al., 2006). This type of information is easily available for any natural language and corpus, and it has been proven to be quite useful to quantify the writing style (Grieve, 2007).

A more elaborate, although still computationally simplistic, approach is to extract frequencies of n-grams on the character level. For instance, the character 4-grams of the beginning of this paragraph would be: |A_mo|, |_mor|, |more|, |ore_|, |re_e|, and so on. This approach is able to capture nuances of style, including lexical information (e.g., |_in_|, |text|), hints of contextual information (e.g., |in_t|), use of punctuation and capitalization, and so on. . .

Stamatatos, E. (2009). A survey of modern authorship attribution methods. Journal of the American Society of Information Science and Technology, 60(3): 538–56.

The above example is of a four character n-gram unit, or 4-gram. The size of the character units can vary from 1 to ten or fifteen (perhaps for those long German compound words).

All of the n-grams are tabulated and listed from the most frequently occurring to the least. The most frequently occurring ones are the author’s fingerprint or profile. How many of the most frequently found units one chooses to use to define the author profile can vary.

So how does one determine what size n-grams to use and what size profile set should one use?

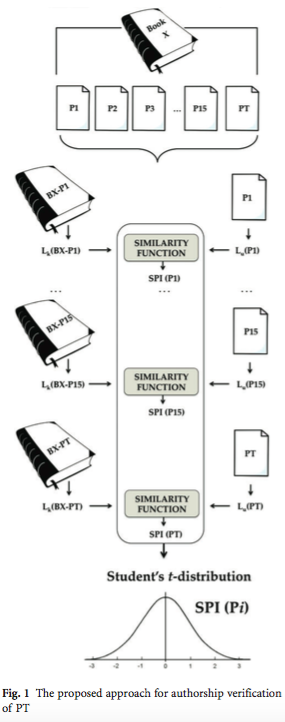

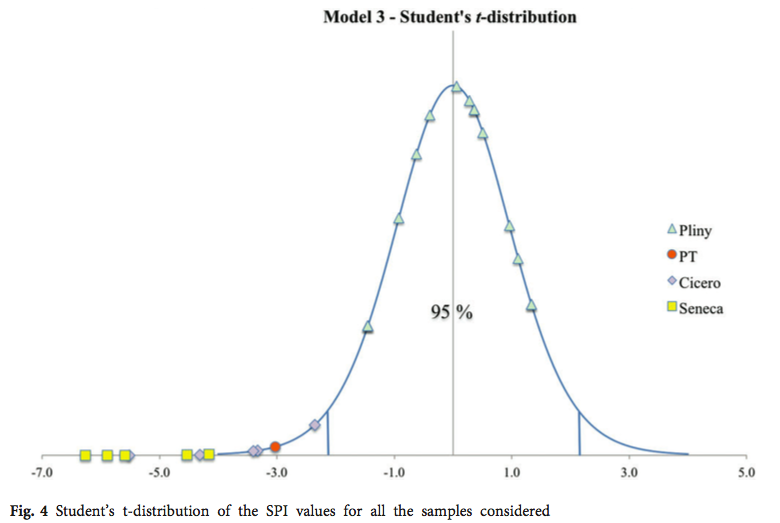

Tuccinardi compared similar sized letters by Cicero and Seneca with Pliny’s Book 10 letters (minus the PT) and found that these were most clearly differentiated from Pliny’s style by use of “five-gram” units and a profile size of 500 of the most frequently found five-character units.

He then applied the same measures in his comparison of the PT with the rest of Pliny’s corpus. Here are the results:

For readers using devices that cut off the right side of the above diagram here is the key you are missing:

The triangular shapes represent each of the fifteen subsections of Pliny’s letters in Book 10. Clearly the PT is as much an outlier as the letters of Cicero, and on the same side of difference as the letters of Seneca are from Pliny’s.

If this sort of testing is new to you you are probably wondering about its validity.

The most convincing proof that a computer-assisted stylometry really works is provided by several controlled attribution tests (Burrows 2002; Hoover 2004a, 2004b; Juola 2006; Juola and Baayen 2005; Jockers et al. 2008, 2010; Eder 2010; Rybicki and Eder 2011; Smith and Aldridge 2011, etc.). The general conception of such a controlled benchmark is to collect a corpus of texts written by known authors only, and then to perform a series of blind tests for authorship. Leaving the technical details aside, the way of testing is simple: the more samples are “guessed” correctly (in terms of being linked to their actual authors), the more accurate a given methodology.

Eder, M. (2011). Style-markers in authorship attribution: a cross-language study of the authorial fingerprint. Studies in Polish Linguistics, 6: 99–114.

and

Character n-grams are able to catch nuances of style including lexical, syntactical, and morphological information. (Tuccinardi, 2016)

Some references in Tuccinardi’s bibliography I found helpful:

- Brocardo, M. L., Traore, I., Saad, S., and Woungang, I. (2013). Authorship Verification for Short Messages using Stylometry. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer, Information and Telecommunication Systems, Piraeus-Athens, Greece, May 2013.

- Brocardo, M. L., Traore, I., and Woungang, I. (2014). Authorship verification of e-mail and tweet messages applied for continuous authentication. Journal of Computer and System Sciences, 81: 1429–40.

- Chen, X., Hao, P., Chandramouli, R., and Subbalakshmi, K. P. (2011). Authorship Similarity Detection from E-mail Messages. Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Machine Learning and Data Mining in Pattern Recognition, New York, NY, August– September 2011.

- Eder, M. (2011). Style-markers in authorship attribution: a cross-language study of the authorial fingerprint. Studies in Polish Linguistics, 6: 99–114.

- Frantzeskou, G., Stamatatos, E., Gritzalis, S., and Katsikas, S. (2006). Source Code Author Identification Based on N-gram Author Profiles. Proceedings of the 3rd IFIP Conference on Artificial Intelligence Applications and Innovations (AIAI), Athens, Greece, June 2006.

- Keselj, V., Peng, F., Cercone, N., and Thomas, C. (2003). N-gram based Author Profiles for Authorship Attribution. Proceedings of the Pacific Association for Computational Linguistics, Halifax (Canada), August 2003.

- Koppel, M. and Winter, Y. (2011). Determining if two documents are by the same author. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 65(1): 178–87.

- Potha, N. and Stamatatos, E. (2014). A Profile-Based Method for Authorship Verification. Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Artificial Intelligence: Methods and Applications, Ioannina, Greece, May 2014.

- Stamatatos, E. (2009). A survey of modern authorship attribution methods. Journal of the American Society of Information Science and Technology, 60(3): 538–56.

- Stamatatos, E., Fakotakis, N., and Kokkinakis, G. (2000). Automatic text categorization in terms of genre and author. Computational Linguistics, 26(4): 471–95.

Pliny the Younger, Book 10, Letter #96.

Pliny to the Emperor Trajan:

It is my practice, my lord, to refer to you all matters concerning which I am in doubt. For who can better give guidance to my hesitation or inform my ignorance? I have never participated in trials of Christians. I therefore do not know what offenses it is the practice to punish or investigate, and to what extent. And I have been not a little hesitant as to whether there should be any distinction on account of age or no difference between the very young and the more mature; whether pardon is to be granted for repentance, or, if a man has once been a Christian, it does him no good to have ceased to be one; whether the name itself, even without offenses, or only the offenses associated with the name are to be punished.

Meanwhile, in the case of those who were denounced to me as Christians, I have observed the following procedure: I interrogated these as to whether they were Christians; those who confessed I interrogated a second and a third time, threatening them with punishment; those who persisted I ordered executed. For I had no doubt that, whatever the nature of their creed, stubbornness and inflexible obstinacy surely deserve to be punished. There were others possessed of the same folly; but because they were Roman citizens, I signed an order for them to be transferred to Rome.

Soon accusations spread, as usually happens, because of the proceedings going on, and several incidents occurred. An anonymous document was published containing the names of many persons. Those who denied that they were or had been Christians, when they invoked the gods in words dictated by me, offered prayer with incense and wine to your image, which I had ordered to be brought for this purpose together with statues of the gods, and moreover cursed Christ–none of which those who are really Christians, it is said, can be forced to do–these I thought should be discharged. Others named by the informer declared that they were Christians, but then denied it, asserting that they had been but had ceased to be, some three years before, others many years, some as much as twenty-five years. They all worshipped your image and the statues of the gods, and cursed Christ.

They asserted, however, that the sum and substance of their fault or error had been that they were accustomed to meet on a fixed day before dawn and sing responsively a hymn to Christ as to a god, and to bind themselves by oath, not to some crime, but not to commit fraud, theft, or adultery, not falsify their trust, nor to refuse to return a trust when called upon to do so. When this was over, it was their custom to depart and to assemble again to partake of food–but ordinary and innocent food. Even this, they affirmed, they had ceased to do after my edict by which, in accordance with your instructions, I had forbidden political associations. Accordingly, I judged it all the more necessary to find out what the truth was by torturing two female slaves who were called deaconesses. But I discovered nothing else but depraved, excessive superstition.

I therefore postponed the investigation and hastened to consult you. For the matter seemed to me to warrant consulting you, especially because of the number involved. For many persons of every age, every rank, and also of both sexes are and will be endangered. For the contagion of this superstition has spread not only to the cities but also to the villages and farms. But it seems possible to check and cure it. It is certainly quite clear that the temples, which had been almost deserted, have begun to be frequented, that the established religious rites, long neglected, are being resumed, and that from everywhere sacrificial animals are coming, for which until now very few purchasers could be found. Hence it is easy to imagine what a multitude of people can be reformed if an opportunity for repentance is afforded.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Awesome! A while back it occurred to me that there were “radicals” who doubted the authenticity of the letter, and that it would be fairly easy to test their hypothesis with linguistic comparison tools, but at that time no one had done this. We’re in a new age of New Testament scholarship.

Part of the problem with the letter is that it leaves one wondering what the supposed Neronian persecution of Christians was all about — why no hint of such an event? So it leads to further questioning of the Tacitus evidence. What has left me cautious has been its stock portrayal of what the Christian narrative would have us expect to find in such a document: Christians are the innocent righteous, whose courage and faith is misinterpreted as ill-tempered stubbornness, and from whose ranks some fall into apostasy. The Roman authorities are also quite Lukan.

Of course that could suggest the accuracy of the Christian portraits but the problem is that we learn nothing new that we did not expect from the Christian story. We would expect independent sources to yield something from a different perspective and to yield some new type of data.

But on accepting its genuineness one does find the absence of “Jesus” from the letter of interest.

Hi Neil.

I have only recently discovered your blog and I am finding a lot to interest me.

I think this type of statistical analysis is a very powerful tool.

However I would have been suspicious of Pliny the Forger’s letter anyway.

When he says ” they invoked the gods in words dictated by me, offered prayer with incense and wine to your image,” he is describing events from the time of the “Crisis of the Third Century” during Decius’ reign (249-251AD) (http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/romans/thirdcenturycrisis_article_01.shtml)

Decius was a devout believer in the traditional Roman Gods and thought the woes of the empire were because the gods were displeased. The barbarians were invading and winning. There was a devastating plague. The empire was in a terrible state. Decius’ remedy was to insist all free men should make a sacrifice to appease the gods. Seen in this light, Decius was not so much persecuting the Christians as expecting them to do their duty.

To the best of my knowledge, there is no record other than from this letter #96 , that there was “persecution” under Trajan (98-117AD). During Trajan’s reign there was no real need to persecute the Christians.

So why does Pliny the Forger place this persecution in the time of Pliny the Younger and Trajan?

Because Decius adopted the name Trajan after victory over his predecessor, Phillip the Arab. He bacame known as and became “Trajan Decius”.

( http://www.viminacium.nl/English%20Traianus%20Decius.html)

Pliny the Forger, writing many years later, may have got the two Trajans mixed up. He may not have not realised that Pliny the Younger served under the earlier Trajan.

Yes, I know it is only speculation, but it is fun to speculate.

Interesting.

“They all worshipped your image and the statues of the gods, and cursed Christ.”

Isn’t it odd that Pliny uses “Christ” instead of “their object of their worship” or some other more general description? I thought Christ is specifically a term used by Christians and only carries the “anointed one” meaning for non-christians at this time… Maybe i’m confusing things?

True. But I have understood Pliny to use Christ here with the understanding that he is speaking of the name of their god. I don’t think Pliny indicates any understanding of the origin or meaning of the term so assumes it is just the name of the god. Even Paul appears to have used the term as an honorific — http://vridar.org/2012/06/27/christ-among-the-messiahs-part-3b/

What is also interesting is that if we set aside the Pliny letter we have no clear-cut non-Christian sources that Christianity had completely set itself apart from Judaism as a different religion until much later. (Being cast out of a synagogue could happen to fellow sectarian Jews — whom other Jews would accuse of “not being true Jews”. (Of course I set aside the passages in Josephus and Tacitus for reasons I think many know.)

I became acquainted with this text because of apologists who like to refer to it trying to establish all kinds of things. And from that i would definitely agree that it would be very upsetting if the testimonium was not original.

The actual message always seemed a bit heavy handed to me (is this really how Romans in charge would discuss such a matter between themselves?), but then, I have little to no experience with similar texts. And why would Pliny use “christ” without ever establishing who or what is meant with that, supposedly the whole reason for the letter is that christians are unknown and obscure to the romans. If Pliny is indeed using it as the name of a god for these christians, wouldn’t it make sense to qualify who or what this “christ” is given the obscurity of what is being discussed?

On top of that, given the dating of the text, and the whole christus/chrestus thing, the letter should be talking about Chrestians/Chrestus if it made it untouched to our time. But i suppose that naming debate isn’t really settled, so that argument wouldn’t get much traction.

Anyway, very interesting, quite a few implications that run counter to mainstream expectations.

Already late H. Detering realized in Adieu Plinius that Christ and God were originally conjoined by an “et” (and), seen in Tertullian’s quotation; the conjunction which got misunderstood as “ut” (as) in the version of Jerome; and, finally, it was replaced by synonymous “quasi”, found in the copy which Dominican librarian Giocondo of Verona had pretended to have discovered.

Dutch Delight mentioned dating. Given that it’s fairly certain (to my mind) that Eusebius forged the questioned passages in Josephus, just how big of a bottleneck were these folks who were copying and preserving and passing on manuscripts? Just how much stuff did they alter and forge? How much can actually be trusted? Because it’s looking like not much.

That’s kind of my question.

Why?

Why forge Tacitus, Josephus, and Pliny? If these three (or even just pick 2) are definite forgeries, then do we question every non-biblical christian/christ reference? What’s the point of forging a few? Why not all. Or if the others are real, why forge 2 or 3? Let the others speak for themselves. What’s the purpose of this?

Its a basic question, and maybe its sounding better in my mind, but I guess it’s the answer we’re seeking…What’s the point?

Historians worth their salt always question their sources. Always. That does not mean they are super-suspicious. It just means they are following the normal rules of human intelligence. Before any source is used to verify information it must always be tested. Can you imagine what history would be like if historians did not do that?

You refer only to questioning non-Christian and non-Biblical sources. I hope you’re not implying that scholars are right not to question Christian and Biblical sources.

The point of such questioning, used selectively (because otherwise it would become apparent that most data can be debunked this way, and thus lead to the well-known obscurantist position that “history is mostly bunk”) is to debunk unwelcome testimony. In this way an “absence of evidence” can be manufactured; and then a claim that “absence of evidence is evidence of absence” made.

Politics and religion cause people to do this kind of selective criticism. The Germans were doing it in the 19th century in order to prove that Jesus wasn’t a Jew, and Christianity did not have Jewish origins.

But sensible people do not do this kind of thing. They derive their information from the data, rather than by finding reasons to ignore it.

In what way selectively? Surely all sources require testing. Of several guides for postgraduate students about to undertake serious historical research one common point is the need to evaluate and assess the authenticity of the sources consulted.

It is far from true that “most data can be debunked” by normal validation processes. Forensic science, court-room battles, genealogical research — they all deploy methods to sift the fraudulent from the genuine.

Historians do the same.

What constitutes the data, though? All sides include some documents and exclude others. Authenticity has to be questioned and probed (remember Piltdown Man, Hitler’s Diaries, the Shroud of Turin?). Useful data for one task might not be useful for another. Shakespeare’s Richard III might not be an entirely accurate retelling of the Plantagenet family feud, but it could provide insight into thoughts about the conflict during the Elizabethan times.

Eusebius certainly forged the Testimonium Flavianum but Origen wrote about the “one who was called Christ” and the John the Baptist passage before Eusebius’ time, so he is innocent of those. That is not to say that those passages were not inserted in the century before Origen got his hands on a copy of Antiquities.

I assume the last 5-6 lines of the text are still referring to Christians?

Why the mention of sacrificial animals and temples in a region near the Black Sea

coast? We are talking about the frontier of the Imperium, where Persia is a constant threat as well as horse peoples from what is now Ukraine.

No mention of developed proto-Nicene liturgy, theology, and Christology.

Also the same region Marcion originates from.

There is a dissertation for the grad student.

The implication is that so many had converted to Christianity that it had affected the business of supplying animals for pagan sacrifices. But after a bit of early pressure sufficient numbers had recanted and returned to their old religion to result in the sacrificial cattle business beginning to pick up again.

Tuccinardi is known in the Italian Net as proponent of the Eric Laupot’s thesis of identity between the historical Jesus and the founder of Fourth Philosophy.

http://independent.academia.edu/EnricoTuccinardi

After the studies of Bernays (1861) and Laupot (2000) who put in evidence the connections existing between the Latin word stirps and its Hebrew equivalent netser, new elements are conveyed to demonstrate that not only Tacitus wanted to turn against the Anti-Roman sect of Christian-Zealots the messianic prophecy of Isaiah 11.1, but that Christ himself, crucified by the Romans, was called Ben Netser.

I’m very skeptical of appications of simple statistical test in almost any social science, but this seems to be the sort of application that lends itself very well to statistical analysis, and my but isn’t that a slam-dunk finding. Hopefully an opponent will pick this up and attempt a replication.

FWIW, Sirpa Montonen in ‘[The English Version of] Jesus Chrestus’ (2010) claimed –

“Pliny the Younger refers clearly in his letter … that the Christian Sect was still worshipping [the] cult religion of Greco-Egyptian Isis and Serapis”

https://books.google.com.au/books?id=XNueDuJy6G4C&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q=serapis&f=false

This is fascinating! It hadn’t crossed my mind that Pliny’s remarks might be an interpolation! The methodology looks really good to my, admittedly amateur, eyes.

Can someone get them to tackle Jophesus’ TF next (original and redacted versions)? Then maybe Paul’s letters, then…the potential list could get pretty long!!

Thanks for this informative post.

I have serious doubts about the origen of Chrstianity. I think if it were genuine then it may have originated here in Asia Minor. It began as a Roman cult in the early 2nd century and added in the more earthly Jewish cast later in the proto orthodox. They wil out over the other worldly Gnostics. That explains earliest texts date to seconf century and there are so few Roman and Jewish references to them

I was suspicious from the start since I know very well with mountains of evidence that Christianity was only invented by Constantine circa 325CE.

From God’s Book of Eskra xiviii, – translation published Salisbury 1921

“Search ye these books, and whatever is good in them, that retain; but whatsoever is evil cast away. What is good in one book, write ye with that which is good in another book. And whatsoever is thus brought together shall be called the Book of Books, and it shall be the doctrine of my people which I will recommend un…to all nations, that there shall be no more war for religion’s sake”

It doesn’t matter whether this too supposedly Constantine’s own instructions is true or false since we only have to examine the Ancient Egyptian belief in their son of God who was surprisingly also called ‘IOSA’ – the name which became Iesous to the Ancient Greeks and Issa to Arabs, but is still ‘Iosa’ in Scots Gaelic Bibles.

Next just read the Septuagint in Greek which was written 2,300 years ago yet has a Book of Iesous and mentions the same name in other Old Testament books. Why then was this very name deliberately mistranslated in later bibles but kept the same in the New Testament?

Read also the hieroglyphic texts in the Temples of Solomon at Luxor and of Hatshepsut at Denderah – these are virtually the same story as the first two chapters of Luke, even showing in accompanying scenes the three men holding up one arm with an offering.

Look too at the Holy Trinity in the tomb of Ymn Twt Ankh Hek Iwnw (means ‘Of the Jews), Shma, Re Heprew Neb where the deceased King David V is shown as the Father Uasar, the Son himself, and the Ka or Holy Spirit.

Next take a look at the mistranslation from Ancient Egyptian in Luke 14:26 which misread the Egyptian Word Msw meaning “Children” as being Greek ‘Mseo’ meaning ‘hate’, ‘loathe’ or ‘detest’.

Then Mark 8:33 where we have a pun on the Ancient Egyptian name Sat (genitive case ‘Satan’) that could mean ‘Sat’ or ‘Set’ evil brother of Uasar, or it could mean Rock as in Petra or Peter.

The Ancient Egyptian stories were all plagiarised by Greek Speaking Egyptian Copts and presented to Constantine who I believe decided to sort out the Jewish problem in Canaan by moving the locality in the finished version.

What makes me very suspicious about Book Ten is that it was added later to the books that Pliny himself finished, plus the locality. The name Khrst too is Ancient Egyptian changing in time from meaning ‘Buried’ to ‘Annointed’ which is what they did in mummifying the dead before burial.

Read the Septuagint version of Isaiah 45:1 and you will find that Cyrus King of Persia is named ‘Christo’ – the Christ. It would make more sense for a Persian people of Bythnia Pontus to be called Christians than the Serapis cult of Ptolemaic Egypt.

Much food for thought here, Malcolm

I have written several posts on historical methods and the valid way for a historian to treat a source text, how to form and test hypotheses, and I fear none of what I have written is found in your speculations. Just take one point from your post.

Can you give us a source to identify what you call the “temple of Solomon at Luxor”?

Can you give us a source so we can see a copy of the texts you are referring to that have “virtually the same story as the first two chapters of Luke”? We would like to see a copy or photograph or authoritative citation to enable us to identify these texts and their translations into English.

Once we have seen those things then we will compare those translated stories with the first two chapters of the Gospel of Luke.

If we see that your claim is indeed correct then we will seek to establish if and/or how the two stories came to be so similar.

Solomon was the Pharaoh Ymn Htp III of this there is no doubt. There are some 20 points to prove it and most are listed in the Appendix and End Notes to my novel. In any case there are a number of books which also name them and discuss each one. Ymn was the Ancient Egyptian God of the Setting Sun and so thought of as the Western Horizon and Heaven – fields of Aarru. The correct translation of YMN (Water Reed hieroglyph + two letter consonant Gaming Board hieroglyph) is AMEN. There is no letter ‘U’ or ‘W’ in this name and it was previously always translated as ‘Amen’, for example in the Greek name for this king – AmEnophis. The mistranslation began in the 1920’s by Americans who were probably disturbed to find that they were addressing an Egyptian God at the end of every prayer.

The second part of the King’s name ‘Hetep’ (the convention is to insert the letter ‘E’ when no other vowel is indicated), means ‘Peace’ or ‘Rest’. Since the 18th Dynasty Kings named Ymn Htp were all Heprew (means ‘Creations’ but is also the origin of the name ‘Hebrew’ – refer Robert Feather and ‘Jesus the Good Scarabaeus’…the Scarab Beetle glyph being ‘Hepre’ plus plural letter ‘w’) he was better known to Hebrew Egyptians as Salim Amen. You should also remember that Israel was at one time Lower Egypt and 1 Samuel 4 to 6 confirms this – just read it carefully!

The Birth Scenes in the palace of Ymn Htp III/Salim Amen III in Luxor are well known. The 4 scenes show the Annunciation, the Conception, the Birth and the Adoration. They are reproduced on page 757 of Gerald Massey’s great work, “Ancient Egypt – Light of the World” and alongside is an explanation of the text in hieroglyphs.

Ymn Twt Ankh Hek Iwnw Shma, Re HEPREW Neb, commonly called Tut today has to have been the missing Prince Twt Ms. This was the eldest son of Solomon – confirmation in the Kebra Nagast which tells us that Meny (Ymn) El (Twt) Ek (Ankh) was also known as ‘David’. It is known that he died young and had been a priest at Iwnw or Memphis and was thought to have taken part in a campaign against Ethiopians. His tomb was found empty and the body missing, but resealed in antiquity with the seal of Ymn Twt Ankh as King. This explains all the secrecy in his re-entombment in the small tomb found by Carter. In that tomb he is shown as God the father, God the Son and their Ka or Holy Spirit. The evidence that Twt or rather David was the missing prince is on the back of the chair found in his tomb which links his name as King – Ymn Twt Ankh Hek Iwnw Shma with his name as Prince Twt Ms. In fact the latter name is in much larger hieroglyphs.

If you email me I can send several word files with the evidence and sources.

I have come across several deliberate mistranslations but once you can read the hieroglyphs these are easily spotted. Also a great lack of knowledge has prevented the truth becoming widely known. For example Egyptian scribes often used shortcut hieroglyphs, even when the spelling of the shortcut was slightly different. In the case of the first four Kings of Egypt named David they are better known by a very garbled version of the shortcut name which glyph was a Sacred Ibis known as Djhwt. When the full separate glyphs are read we see that their names were just DHWT – something like ‘Dayhut’. ‘Djhwt’ is then often followed by the adjectival suffix ‘Y’ which simply means “He Who Is” – very similar to the use of ‘Y’ after English names, like Billy and Tommy. Then again we often see the name followed by the Foxglove hieroglyph – “MS” which just means ‘Born of’. Consequently Djhwty Ms has been chucked at us in the form of ‘Tuthmosis’ – nothing like the real name David. Another point made by historian Ahmed Osman in his “Out of Egypt – the roots of Christianity Revealed” is that TWT was a later abbreviation and in Hebrew it becomes DWD which does translate to ‘DAVID’. This book was republished with a new name, “Christianity an Ancient Egyptian Religion”.

Most Cartouches, only used for names of Kings, begin with a God name. This is usually RA or RE which we still find in ‘Rachel’ and REbecca (became Beketaten during the Aten period), or YMN – Amen, but also very importantly and one that is missed by just about every Egyptologist is the Double Water Reed which spells YY. When a letter is repeated it becomes plural and is never YY, but spoken with the plural letter W, and so “YW” or “IU” (Jew). Whilst Massey knew this I’m fairly sure that he didn’t have solid confirmation. But I found it in the Irish legend of the blood feud between Brothers Brian (Pharaoh Ibram), Iuchar (Pharaoh IU + HR or Horus), IUchabar (Pharaoh YYkhbr – IUcheber) with Kian (Pharaoh KH IU an). The names in the Irish legend have the very same names of the Egyptian Kings in their Cartouches!!!

Forget the false claim by Hawass that King Twt was a son of Akhenaten. This is not at all true and Kate Phizakerley has a page on the net showing that dna proves that this lie cannot be true. Besides 4 Stela, as well as the Kebra Nagast all say that Twt was the son of Solomon – Salim Amen III.

The actual dna has been locked away by Hawass and his troupe and we can see why. But Igenea of Switzerland picked it up from a video clip of a monitor showing the dna analysis and these Kings were R1b1a2 which is the dominant ydna of males in the British Isles – up to 90% in England alone. There just has to be some truth in the legend of the Princess Scota giving her name to the Irish and Scottish tribes. That would mean that Scota is a Goddess name and that would have to be Skhety – Goddess of the lands, Marshes and common people.

The truth is far more fascinating than the fiction we have always been fed. All the best, Malcolm

I will prefer to use scientific methods for establishing doubts about Pliny’s letter and also to interpret the evidence we have in Egypt, Ireland and elsewhere. When you look for matches to words here and there you will always find what you are looking for. Scientific method is about falsification — as per my recent post on method: https://vridar.org/2018/07/25/how-a-historian-establishes-what-happened-when-we-only-have-the-words-of-the-text/

@ Neil.

A point I had not considered before and a definite eyebrow raiser.

This got me thinking about the complete (apparent) lack of any reference to a human figure behind this new ”cult”.

Surely those who were tortured would have been questioned about the source of their belief?

And I doubt torture would have involved a feather duster and repeated requests of :

”Aw, go on tell us ….”

One has to wonder what those who were tortured revealed.

They must have known about the character behind the cult and yet, as you note, Pliny betrays no knowledge of such a figure.

”Curiouser and curiouser.”

I don’t know if there would have been much interrogation about the finer points of their beliefs. They were required at certain times to participate in some form of worship or sacrifice to the emperor’s image. If they refused I can’t imagine magistrates asking too many questions. If they refused, they suffered the penalty. Philosophers who were found or deemed to be disloyal to the emperor might be ordered to commit suicide. The emperor wasn’t interested in knowing the whys and wherefores.

I think of Paul’s Christianity as something more akin to a philosophical school (there was not a huge difference between certain philosophers and religious teachers: both could speak of God and both would give due honour to the deities.) —

Paul’s Christians would identify as a new and separate people with a special devotion to their god above all others; I don’t know how often they would have been confronted with life and death situations over demands to worship the emperor.

That’s why I was thinking of the way Domitian and Hadrian went to extra lengths to enforce or promote the imperial cult. I suppose at such times there was a risk of Christians being caught by surprise.

I get the impression many Christians saved their necks by sacrificing anyway. If it’s true that the Marcionites were subject to persecution more than the “proto-orthodox” it’s a shame we don’t have their accounts of why and how often.

It seems ”If” is always the operative word when it comes to ”Christian Tales.”

As always, an interesting and informative post.

Thanks.