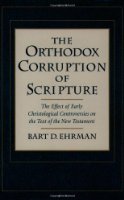

A Jewish scholar, Joshua Efron, believes that the entire “stoning of James” passage — yes, that James who is said to be “the brother of Jesus who was called Christ” — in Josephus is a Christian forgery.

Now Efron does get under the skin of a few scholars when he argues with a sometimes abrasive style contrarian views relating to the Hasmonean period of Jewish history, Christian influence in the Pseudepigrapha and views on the Dead Sea Scrolls, but I have not read a rebuttal of his arguments about the existence, function and character of the Sanhedrin in the Second Temple period. I would be interested in doing so. Josephan scholar Louis Feldman acknowledges Efron’s “enormous learning”.

Of the New Testament references to the Jewish Sanhedrin Efron writes:

The New Testament Synedrion (Sanhedrin) was created in the bosom of Christian theology, nurtured by its characteristic tenets and trends in order to provide a concrete, albeit artificial representation of Jewish leadership that denies and contemns the wondrous heavenly savior. (337f)

Efron’s detailed survey of the evidence and all references to the word translated “sanhedrin” that the common image we have of a supreme ruling Sadducee body at the time of Second Temple Judaism is an anachronistic myth:

It is not purely terminological details but facts that prove the non-existence of the Great Sanhedrin at the end of the Second Temple period. Here Josephus appointed at his side in Galilee a high council of seventy in exercising his authority to judge criminal cases, and the zealots in Jerusalem set up a tribunal of seventy for capital cases. In these two salient cases there is no indication of any coordination or contact or of conflict with the sacred rights of the Great Sanhedrin in the Chamber of Hewn Stones which alone was supposed to have seventy members. A Gerousia of the Jewish community of Alexandria, mentioned by both Philo and Josephus, had “seventy elders” in it according to the talmudic legend, with no reference at all to the supreme institution in Jerusalem. All these testimonies lead to the solid conclusion that from the time of the Return to Zion up to the destruction of the Second Temple there were representative, administrative, public bodies, intermittently appearing and disappearing as Gerousia, and Synedrion and Boule, but they were never identifiable with the talmudic Great Sanhedrin at the head of the judicial system that defines the law and disseminates the Torah among the people of Israel. (318)

With that background perspective, read again about the stoning of James in Josephus’s Antiquities. I have set Efron’s paraphrase alongside the Whiston translation. The sentences in italics are Efron’s introductory and concluding commentaries on the scene.

| Josephus: Antiquities 20.9.1 (20:197-203) | Efron’s paraphrase of Josephus: Studies, p. 334 |

| AND now Caesar, upon hearing the death of Festus, sent Albinus into Judea, as procurator. But the king deprived Joseph of the high priesthood, and bestowed the succession to that dignity on the son of Ananus, who was also himself called Ananus. Now the report goes that this eldest Ananus proved a most fortunate man; for he had five sons who had all performed the office of a high priest to God, and who had himself enjoyed that dignity a long time formerly, which had never happened to any other of our high priests. | |

|

The second passage pictures an evil, harsh Sanhedrin, very similar to the one in the New Testament. |

|

| But this younger Ananus, who, as we have told you already, took the high priesthood, was a bold man in his temper, and very insolent; he was also of the sect of the Sadducees, who are very rigid in judging offenders, above all the rest of the Jews, as we have already observed; when, therefore, Ananus was of this disposition, he thought he had now a proper opportunity [to exercise his authority]. Festus was now dead, and Albinus was but upon the road; so he assembled the sanhedrin of judges, | The younger Ananus (or Annas), the high priest, son of the elder Ananus, was extremely bold and brazen, belonged to the Sadducees, who were severe (“savage”) in trial more than any Jews, took advantage of Festus’ death and before the arrival of the new procurator Albinus, “seated a Synedriort (Sanhedrin) of judges,” |

| and brought before them the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James, and some others, [or, some of his companions]; and when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned: | brought to trial James the brother of Jesus, “called the Messiah (Christ),” and also “certain others,” accused them of violating the law “and delivered them to be stoned.” |

| but as for those who seemed the most equitable of the citizens, and such as were the most uneasy at the breach of the laws, they disliked what was done; they also sent to the king [Agrippa], desiring him to send to Ananus that he should act so no more, for that what he had already done was not to be justified; | However, circles among the residents of the capital considered “the most fair-minded and most strictly law-abiding” did not wish to tolerate such an injustice and applied secretly to King Agrippa to obtain his order preventing such deeds, for Ananus did not act properly to begin with. |

| nay, some of them went also to meet Albinus, as he was upon his journey from Alexandria, and informed him that it was not lawful for Ananus to assemble a sanhedrin without his consent. | Some of them set out to meet Albinus and explained that Ananus did not have the authority “to seat a Sanhedrin” without the procurator’s consent. |

| Whereupon Albinus complied with what they said, and wrote in anger to Ananus, and threatened that he would bring him to punishment for what he had done; on which king Agrippa took the high priesthood from him, when he had ruled but three months, and made Jesus, the son of Damneus, high priest. | “Albinus was convinced” and angrily wrote an irate and threatening letter to Ananus. That is why Agrippa also took the high priestly crown away from him. |

|

So ends the episode, which at first glance seems free of weaknesses and faults. And yet a careful examination collapses this naive testimony. |

Here are Efron’s objections to a naive reading of the passage. Continue reading “Is the Entire James Passage in Josephus an Interpolation?”