In the previous post we saw that Tacitus’s account of Nero’s persecution of the Christians is, given the ratio of number of words analyzed to the number of words published about them,

this handful of sentences is beyond doubt the most researched, scrutinized, and debated of any in Classical antiquity.

What sorts of questions bedevil the scholars? And what are we to make of a passage that throws up such a cluster of confusions?

Here is a list of the problems as pointed out by Anthony Barrett in his chapter five, “The Christians and the Great Fire”:

Annals 15.44.2. But neither human resourcefulness nor the emperor’s largesse nor appeasement of the gods could stop belief in the nasty rumor that an order had been given for the fire. To dispel the gossip Nero therefore contrived culprits on whom he inflicted the most exotic punishments. These were people hated for their shameful offenses whom the common people called Chrestians [or Christians].

44.3. The man who gave them their name, Christus, had been executed during the rule of Tiberius by the procurator Pontius Pilatus. The pernicious superstition had been temporarily suppressed, but it was starting to break out again, not just in Judea, the starting point of that curse, but in Rome as well, where all that is abominable and shameful in the world flows together and gains popularity.

44.4. And so, at first, those who confessed were apprehended and, subsequently, on the disclosures they made, a huge number were found guilty [or “were linked”]—more because of their hatred of mankind than because they were arsonists. As they died, they were further subjected to insult. Covered with hides of wild beasts, they perished by being torn to pieces by dogs; or they would be fastened to crosses and, when daylight had gone, set on fire to provide lighting at night.

44.5. Nero had offered his gardens as a venue for the show, and he would also put on circus entertainments, mixing with the plebs in his charioteer’s outfit or standing up in his chariot. As a result, guilty though these people were and deserving exemplary punishment, pity for them began to well up because it was felt that they were being exterminated not for the public good, but to gratify one man’s cruelty.

Translation by Anthony Barrett (pp. 263f)

1. Linked with them?

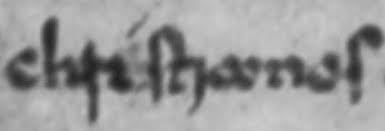

In 44.4 of the fifteenth book of Annals the text appears to say that many persons were “linked” with those who confessed. What does “those who were linked” to the confessors mean? It is possible that we are reading a copyist’s error here. It is easy to imagine that the original sentence read “were convicted”.

- coniuncti sunt = were linked

- convicti sunt = were convicted

It is easy to assume that a copyist has erred but Barrett does remind us in an endnote that the verb “to link” is found in similar legal contexts in Cicero’s works.

. . . we cannot know if this obscurity is because of a manuscript error or simply because of the opacity of the narrative. The emendation convicti may well be correct, but clearly we should always be hesitant about basing any interpretation of a key controversial passage on a word that does not actually appear in the manuscript(s). (Barrett, p. 146)

2. Crucified and burned as human torches?

English translations hide the difficulty in the fifteenth-century manuscript. To turn to another work cited by Barrett, Roman Attitudes Toward the Christians by John Cook (2010), we read the “original”:

et pereuntibus addita ludibria, ut ferarum tergis contecti laniatu canum interirent, aut crucibus adfixi aut flammandi, atque ubi defecisset dies in usum nocturni luminis urerentur.

Outrages were perpetrated on the dying: covered with the skins of animals they died mutilated by dogs, or they were fixed to crosses, or [burning], and when daylight faded they were burned for nocturnal illumination. (Cook, p. 69 – my highlighting in all quotations)

Cook lists the various proposed emendations to make sense of the passage. Some scholars have deleted the phrase [“or fixed to crosses of burned”] entirely as a gloss. Others have read it as “or fixed to crosses and burned”. Another has deleted “so that burning” and adds, “they dressed in fuel for fire”. Another, “or fixed to crosses and burning, when…”; and others have reordered the words to place “so that” before “burning”. And so forth.

In other words,

we can not be totally sure of the exact wording of the original manuscript. (Barrett, p. 147)

3. Chronology is vague

Tacitus is very clear that the fire itself started July 19, AD 64, but he is unclear how long after that until Christians were said to be rounded up. Barrett’s conclusion:

. . . we can assume one of two things— either that [Tacitus] had found in the record that the punishments had occurred before the end of the year, AD 64, or that the source he was using was vague about when they happened and on his own initiative he determined that the second half of AD 64 best suited the material. (p. 148)

Suetonius also informs us that Nero inflicted punishments on Christians but he sets this occasion long after the time of the fire and one has a hard time thinking the passage refers to the horrendous tortures we read about in Tacitus:

Under [Nero’s] rule, many practices were reproved and subject to controls and many new laws were passed. A limit was imposed on expenditure. Public feasts were reduced to food handouts. With the exception of beans and vegetables, the sale of hot food in taverns was prohibited—previously all kinds of delicacies had been available. Punishments were imposed on the Christians—adherents of a new and dangerous superstition. A ban was placed on the diversions of the charioteers, who for a long time had taken advantage of the freedom they enjoyed to wander about the city playing tricks on people and robbing them. At the same time, the pantomime actors and their associates were outlawed from the city. (Suetonius, Life of Nero, 16)

4. The Sect was temporarily suppressed?

This is a curious claim since we have no record anywhere else that the following of Jesus “was suppressed” soon after his crucifixion. The sources we do have suggest that Rome would have had no interest in the earliest manifestations of the new movement. Christianity was from its earliest days viewed as a Jewish sect and Jews were free to practice their religion at this time.

Another Roman historian, Suetonius, wrote that twenty years before the Great Fire Jews were expelled from Rome because they had been “creating disturbances at the instigation of Chrestus”. Was this a reference to Christ? Were the disturbances of the kind we read about in Acts when Jews sometimes became riotous over the preaching of Jesus Christ? We know that Chrestus was a common mispronunciation of Chrestus. On the other hand, Chrestus was a common name among freed slaves. It certainly does not look like a good fit for the claim we read in Tacitus’s Annals that the Christian sect was suppressed soon after it emerged in Palestine.

4. A Huge number?

A “huge number were found guilty”, we read in Annals. How many is that? How large should we expect to find the Christian community in Rome at that time? Were they distinctive enough to stand out as separate from the other Jews? Besides…

The “huge number” of the Annals may, of course, be an exaggeration, and in any case the figure is essentially relative, meant to draw a contrast between the initial group who confessed and the later group who were rounded up. If no more than two or three people were involved initially, and we have absolutely no way of knowing, then a subsequent arrest of, say, thirty people, could, relatively speaking, constitute a “huge” number. (Barrett, p. 150)

5. How much hatred?

In Tacitus and Suetonius we are faced with the language of extreme loathing towards Christians. They are justly “hated for their shameful offenses” and for the “abominable and shameful things” that they bring to Rome. But such language informs us more about the elitist attitudes in these second-century authors and not necessarily the general attitude in mid-first-century Rome. Barrett suggests “it seems highly unlikely that the deep and pervasive antipathy” of later Romas was extant as early as the 60s. Civil disturbances as we find in Acts is one thing; suspicions of human-hating behaviour so soon is another.

6. Confessed and apprehended

Once we read that Nero decided to scapegoat the Christians we immediately come upon a baffling reverse of a normal process: “And so, at first, those who confessed were apprehended” [=igitur primum correpti qui fatebantur]. One expects confession to follow the arrest. A couple of scholars (Getty, Ash) have suggested an amendment (qui to quidam) to the text so that it reads “Certain individuals confessed after being arrested.”

Barrett highlights the problem:

Also, to what are these people confessing? Given that upon conviction those arrested were subjected to the most horrific punishments, and that on the basis of the testimony of those who confessed, others became implicated “more because of their hatred of mankind (odio humani generis) than because they were arsonists,” it does follow that the group initially arrested must have confessed to arson.

But if this is the case, the narrative is cryptic and contradictory. When Tacitus introduces his account of the fire, he indicates that there were two possible causes. Either (a) it was an accident, or (b) Nero was responsible. We might argue that he had tunnel vision on this issue, albeit less narrow than that of Suetonius and Dio, and that the situation was far more nuanced than Tacitus imagines. The fire could have been started deliberately, but by someone other than Nero, or it could have started by accident, then once it had taken hold it could have been helped along. The issue here is not what actually happened, but what Tacitus says happened: Nero, to deflect criticism, “contrived culprits” (subdidit reos). There is no ambiguity—the word “contrived” (subdidit) leaves no doubt whatsoever that the charges were bogus. And yet those culprits seem to have been taking responsibility for the deed. Of course there may have been special circumstances that led to this outcome, but if so, Tacitus does not explain them, and perhaps that was deliberate. It would appear that the Christians, as often happens in cases of wrongful conviction, were already unpopular for anti-social behavior that had nothing to with the Great Fire. They may not have committed the crime, but criminal by nature they were. If, however, they were being scapegoated for the arson, it seems to mean they can have confessed to only one thing, and that is, of being Christian. Does this mean, then, that Christianity was in itself a crime in AD 64? (Barrett, pp. 152f)

If there had been an edict declaring Christianity illegal we would expect it to apply throughout the empire. Yet there is no evidence of anything like this. Pliny the Younger’s testimony of fifty years after the Great Fire clearly implies that there had never been a universal ban, although I think the evidence that that letter of Pliny’s is not authentic is strong.

A potentially confusing situation

Hence we find ourselves in a potentially confusing situation. We have no precise information about the grounds on which the Christians were condemned—the charges are vague and undefined. And the presiding magistrate would have had the authority to make up his own mind about the allegations, whatever they might be, provided the accused were not Roman citizens, which was probably the case for the overwhelming majority of early Christians in the city. There may have been a belief, well grounded or not, that the Christians had been responsible either for starting the fire or at the very least for feeding the flames once it had taken hold. The Annals claim that the initial suspicions were deliberately sown by Nero, but we must be open to the possibility that if there was in fact action against the Christians after the fire, it might have had little or nothing to do with Nero and that the claim in the Annals that he falsely targeted them as suspects is totally speculative. (Barrett, p. 155)

Imagine a situation of public hysteria. Christians were blamed and were equated with arson in a manner similar to the way we have seen Muslims guilty of terrorism by association. Perhaps the situation was confusing and the account of Tacitus is confusing for this reason. Yet, recall the opening quotation of the previous post. Tacitus knew how to create suspicions in a reader’s mind behind his protestations of scepticism towards “baseless rumours”.

As Yavetz put it, “Tacitus did not want to clarify but to confuse the reader even more—slightly incriminate both Nero and Christians, both of whom he hated.” . . .

. . . But, as stated earlier, at issue here is not what happened, but what the Annals say happened. And their author seems to have gone out of his way to try to pull the wool over our eyes. (Barrett, p. 157)

At this point Anthony Barrett bravely wades out into deeper waters where few of his peers have been prepared to go. To be continued in the next post.

Barrett, Anthony A. Rome Is Burning: Nero and the Fire That Ended a Dynasty. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2021.

Cook, John Granger. Roman Attitudes Toward the Christians: From Claudius to Hadrian. Tübingen: Coronet Books, 2010.