Biblical scholars are not a unique species. Though many of them do seem to be unaware that they are presenting a one-sided view of the evidence, and indeed they are often blind to the logical flaws in their arguments, but they are not alone. As I recently posted here:

I have in the past few months discovered that this is not a flaw restricted to biblical scholars. I have encountered the same wishful thinking and flawed methods of argument among Classicists who desperately seem to want a certain first hand account of a Christian martyr, and woman as well, to be authentic. So I have to have a bit more understanding of the foibles of biblical scholars, I guess.

Below is my essay that illustrates exactly how some Classicists in a certain niche area of study display some of the same kinds of flaws as biblical scholars. The blemishes too easily come to the fore when scholars believe they are face to face with the earliest evidence for Christian origins and therefore want to find ways to accept a core base of those sources as authentic — rather than accept the fictional character that is normally associated with that kind of evidence.

Perpetua was a female Christian martyr in Carthage in the year 202 CE. You can read a little about her and the account of her last days attributed to her on Wikipedia. I will add a few side boxes to supplement my original essay where I think it might make it more useful for general readers. (The original essay was submitted as an assignment task in a course I am currently undertaking at Macquarie University.)

How Historians Have Engaged With Perpetua’s Account of Her Final Days in The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity

It seems a wise principle that the burden of proof rests on those who doubt or reject the textual data from antiquity, not on those who accept them. . . . [T]he proof must be provided by those who question the ancient data.[1]

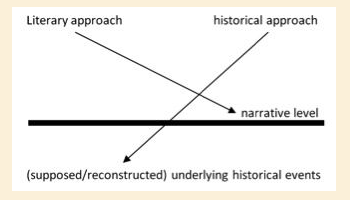

In response to the above words of Vinzent Hunink, this essay seeks to demonstrate that several arguments for the authenticity of Perpetua’s authorship of her prison experiences in The Passion Of Saints Perpetua And Felicity (Passio) are flawed logically and lack the independent support historians normally rely on to establish ancient claims. In doing so I will refer to alternative approaches of other historians. By authenticity I mean the proposition that the author of Perpetua’s account in the Passio was the historical Perpetua martyred at Carthage around 203 CE.

Hunink provides three grounds for accepting the authenticity of Perpetua’s prison diary:

(a) its “marked stylistic features and personal details”,

(b) Hunink’s inability to imagine a reason for it not being written by Perpetua,

(c) and the Passio’s statement that Perpetua wrote her account.[2]

In objecting to doubts whether Perpetua was an actual author, he writes

there should be grave, compelling reasons to make us reject the evidence from antiquity as far as authorship is concerned.[3]

Hunink is here equating “the textual/ancient data” (i.e. the written document) from which we build a hypothesis (i.e. that it was authored by such-and-such) with the “evidence” called upon to test that hypothesis. It is circular to claim that the data explained by our hypothesis itself is the evidence that confirms our hypothesis. This particular protest against doubts is logically flawed.

Jacqueline Amat’s critical edition and discussion of the Passio is widely cited and a work to which scholars have been said to owe a “permanent and immeasurable debt” for its “outstanding” contribution.[4] I will therefore refer repeatedly to her work. Amat stresses the authenticity of Perpetua’s account by appealing to

(a) its independently verified historical context;

(b) its literary style;

(c) and the realism of her dreams.

Amat thus recognizes the importance of providing an independently verifiable and datable historical context:

Sévère ordonnait de poursuivre tous les nouveaux convertis. L’arrestation de Perpétue et de ses compagnons s’insère donc dans une politique de répression des catéchumènes.[5]

Amat points to Eusebius, the Historia Augusta, and works by J. Moreau and W.H.C. Frend to learn of this specific repression. Unfortunately none of these references provides the external support Amat seeks. Eusebius has been judged (a) as relying more on his ability to invent a history “the way it should have been” according to his apologetic perspectives[6] and (b) as being motivated for personal reasons to dwell on multiplying and glorifying instances of martyrdoms.[7] Moreau and Frend use tentative language when speaking of the edict: “Les modalités d’application de l’édit de 202 sont mal connues dans le détail”;[8] “Eusebius was largely ignorant of events in the west”, “for the sake of dramatic effect”, “do not contradict”, “ring of truth”, “balance of probabilities”, “falls short of proof”, “relatively truthful”, “circumstantial evidence”.[9] By identifying this edict with the one reported of Severus in Historia Augusta, moreover, Amat contradicts the statement by Timothy Barnes that it is “demonstrably fictitious”.[10] This is striking since Amat relies on Barnes in the same journal of the previous year to establish her next point. By overlooking studies from the 1960s that address reasons to doubt the historicity of the Severus decree, even concluding it “to be an historical fiction”,[11] Amat’s reading of the evidence is over-selective. Finally, the Passio itself indicates that Perpetua was deeply knowledgeable in the Bible so one must wonder if she had been the kind of new convert the decree supposedly targeted.

The next independently attested item cited is the matching of Perpetua’s date of martyrdom with the birthday of Geta, information that arguably could only have been known to a contemporary of Perpetua given the state-ordered erasure of all memory of Geta after his death. While Amat relies on the argument of Barnes here,[12] Ellen Muehlberger points out that Barnes’ case is based on one manuscript that differs from others.[13] Amat appeals to J. A. Robinson’s surmise that copyists removed the name Geta in light of the damnatio memoriae.[14] Like Hunink, Amat is effectively claiming as evidence for the hypothesis the data the hypothesis claims to explain – that Passio was composed in the time of Geta. A genuinely independent assessment of the hypothesis (assuming that the name Geta was in the original work) would also compare other possible explanations that posit the flavour of historicity being a literary artifice – as provided by Thomas Heffernan:

[T]he redactor is at pains throughout the narrative to provide historical veracity . . . so as to promote [Perpetua’s] value as being equal to the “old examples of the faith” . . . . The allusion to Geta thus complements the redactor’s historicizing intent, which is to legitimate the New Prophecy among his fellow communicants.[15]

Ironically, in making this point, Heffernan attributes to Perpetua an authentic voice behind words that conflict with it—an inconsistency more easily explained by a single author.

The final appeal to independent verification for the authenticity of the Passio is the assertion that Perpetua’s contemporary Tertullian mentions it.[16] Tertullian may indeed have known of the Passio but his actual words can only be taken as a reference to the text if one already assumes that it existed in his time:

Quomodo Perpetua, fortissima martyr, sub die passionis in reuelatione paradisi solos illic martyras uidit, nisi quia nullis romphaea paradisi ianitrix cedit nisi qui in Christo decesserint, non in Adam?[17]

That Tertullian confuses the dreams of Perpetua and Saturus in the Passio is forgiven by Amat and other scholars as normal human memory lapse. The data does not fit so it is forgiven and still interpreted as confirming the hypothesis. A more rigorous investigation ought to consider an alternative proposal that potentially has wider explanatory power: that Tertullian knew of a free-floating Perpetua story that was later written down. That alternative is able to explain not only Tertullian’s contradiction but also the apparent loss of the Passio until the time of Augustine who initially expressed doubts about its authenticity.[18]

Thus Amat’s attempts at setting a historical date and context for the Passio begin with the assumption that it contains an authentic historical account and then set aside contrary independent evidence and explanations.

To avoid circularity it is necessary to turn to relevant external or independent data. This is the approach of Ellen Meuhlberger:

On this point about Augustine — I failed to address the fact that Augustine is also evidence of public commemoration of Perpetua and Felicity being observed prior to his time. This failure could be seen as my own “lack of balance” in the discussion at this point.

The most valuable tool readers have to contextualize any text is its reception. . . . The first writer to make precise reference to Perpetua’s account is Augustine of Hippo . . . of the fifth century. . . .[19]

Not only do we have no indisputable evidence that the Passio existed until the fourth century, but when we do find it mentioned, it happens to express the ideas found in other texts of that later time:

. . . a text that expresses themes evidenced in the fourth and fifth centuries may well itself be a product of the fourth and fifth centuries.[20]

Since Robinson the primary argument that has reportedly swayed most scholars to embrace authenticity has been about Perpetua’s style.[21] But what is it about this style that convinces? For Amat, authenticity is demonstrated by “strikingly beautiful” words in the face of death, so beautiful that they “can hardly be considered apocryphal”:

Elle est soutenue par la certitude qu’au moment de sa passion le Christ sera à ses côtés et ce sentiment lui dicte une fort belle réponse, qu’on ne peut croire apocryphe (15, 6).[22]

Yet two pages earlier Amat had appealed to content far from beautiful as grounds for believing the work to be authentic:

Saturus affronte le martyre avec ses défauts [sc. d’une fierté un peu trop orgueilleuse, d’une intransigeance un peu trop mordante] et c’est là un gage de l’authenticité du récit.[23]

So both beautiful and the less beautiful are felt to be signs of authenticity. Here we are surely encountering another instance where a case is “guided by a telos of confirmation, rather than exploration.”[24]

A different stylistic feature is identified as a marker of authenticity by Brent Shaw. Not strong beauty or the introduction of embarrassing character flaws but the plain, prosaic “simple reportage” of her experiences, an “unmediated self-perception, her reality” now becomes the stylistic evidence of authenticity:

Perpetua’s words . . . differ so much in the fundamental aspect of simple reportage from all other so-called “martyr acts” . . . . Hers is a direct account of actual human experience, a piece of reportage stripped of … illusory rhetorical qualities . . . . [T[here is something, perhaps ineffable, that marks her words as different in kind from any comparable piece of literature from antiquity.[25]

Amat saw both the sublime and the flawed as witnesses of authenticity; Shaw appeals to unadorned “simple reportage”. Yet in a footnote Shaw concedes that the simplicity and directness of the language could after all be “the result of conscious or semiconscious ‘rhetorical’ strategies as much as anything else”.[26] Such a concession surely undermines his main point that the simplicity of the account was the sure sign of it being of direct and unmediated reportage.

Even scholars who have discerned aspects of style that were not likely penned by Perpetua have still clung to the view of Perpetua being the ultimate author, suggesting that she knowingly left her words to be adapted by recorders or editors.[27] (See the quote at note 15 above.) Such scenarios look like ad hoc attempts to maintain a case for authenticity as appreciation for stylistic features has deepened since Robinson.

Eric Dodds is also convinced that Perpetua’s account is authentic by

(a) the simplicity of style,

(b) it being “entirely free from marvels” (he overlooks the miraculous cessation of lactation)

(c) and its dreams being “entirely dreamlike”.[28]

Where “another author”, the redactor, has provided an account that complements or comments on Perpetua’s statement both Dodds and Shaw cannot imagine that these additions might be part of a common project to produce the Passio.

[T]his unmediated self-perception, her reality, was subsequently appropriated by a male editor . . .[29]

[C]ertain incidents appear to have been introduced in order to provide a fulfilment of prophecy. . . .[30]

Shaw and Dodds, on the presumption of authenticity, thus treat Perpetua’s journal without reference to “the textual data” of the Passio’s whole.

Two scholars against whom Hunink was protesting when he appealed for a prima facie acceptance of the “textual data” actually are more consistent in their acceptance of that data than Dodds and Shaw. Shira Lander and Ross Kraemer accept the Passio as a literary unity and accordingly find a two-way dialogue between Perpetua’s story and its surrounding text that is suggestive of a unity Shaw and Dodds deny:

[T]he startling degree to which details of the Passio conform to the biblical citation of Joel 2:28–29/Acts 2:17–18 in the prologue . . . contributes to our concerns. It is possible, indeed perhaps tempting, to read the Passio in its present form as a narrative dramatization of this citation . . . . Many elements of the Passio conform closely to the particulars of this prophecy. . . . The extraordinary emphasis on Perpetua’s role as a daughter . . . . coheres exceedingly well with the characterization of the female prophets as daughters.[31]

Whether one accepts this interpretation or not, it can be acknowledged that it is firmly grounded on Hunink’s “textual data” itself. Surely any “textual data” can only be fully understood if read in the context of the literary heritage of its author, or with reference to texts independent of the one being studied. Authenticity is a proposition that needs to be argued, not assumed.

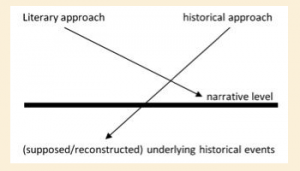

Hunink was focussed on the content of the Passio (e.g. noting the editorial claim that Perpetua wrote her own story). He failed to appreciate the way the Passio “worked” as a literary composition. As Megan DeVore noted, Hunink allowed the flaws in Erin Ronsse’s article to blind him from her more substantial point: its literary sophistication. Ronsse attempted to make this point by detaching it from the question of authenticity but the authenticity question could not be ignored.[32] DeVore takes the literary unity of the Passio much farther by identifying intertextuality with other early Christian texts and engagement with teachings and images in Clement of Alexandria and Hermas. It is the editorial frames that work with Perpetua’s account to create a “collective memory” because of their allusions to other early Christian literature. For DeVore (and as I mentioned above) a richer understanding of any literary work requires reading it in the context of other works of its era and in the light of ancient rhetorical theory.[33] DeVore even treats Perpetua as an authentic author,[34] but an argument for literary sophistication undermines the reasons others have believed in authenticity.

One detail illustrates how different assumptions lead to different conclusions over authenticity. Dodds was confident that Perpetua’s dream of being given cheese was a sure sign that the dream could not be “a pious fiction” since the image had no relevance to Christianity at the time.[35] DeVore, however, by widening the frame of reference through which we read the Passio shows that cheese did indeed have directly relevant Christian symbolic meaning in Clement’s Paedagogos.[36] The image was there to be deployed by Perpetua or any other author.

Peter Dronke illustrates the dilemma arising when simplicity of style is taken as the rationale for authenticity. Dronke cannot ignore “the writer’s artistry” but feels uncomfortable that he notices it at all. What is “artless” is “artistry”. He dares not praise it.

From the outset we see that Perpetua . . . is not striving to be literary. There are no rhetorical flourishes, no attempts at didacticism or edification. The dialogue is (I think deliberately) artless in its shaping . . . . [S]he was recording her own outer and inner world . . . with shining immediacy. . . . Where writing wells up out of such fearsome events, it seems impertinent, or shallow at best, even to praise the writer’s artistry. . . . [S]he did not try to make her experience exemplary.[37]

If “deliberate”, surely it cannot be said to be “artless”, and if it did not seek to be edifying, one must ask why it was read for edification among believers through the centuries.

Many authors have long understood the potential power of a simple narration and Dronke seems to be torn between being guiltily impressed by “the writer’s artistry” and a contradictory belief that it fundamentally really is what it strives to be without literary manufacture. But literary art with emotional impact does not have to be infused with baroque flourishes. It can appear very simple and natural. Megan DeVore shows how Perpetua’s account of herself coheres with literary principles set out by Aristotle. What appears brief and disjointed in the narrative – “lacking literary artifice”, one might say – can draw a reader in to appreciate the nobleness of Perpetua’s character:

While . . . narrative of section 9 seems prima facie to be little more than a disjointed rendering of two events, the seemingly laconic section relays a significant rhetorical antithesis and further develops the image of Perpetua for her audience.[38]

Perpetua’s dreams have also been viewed as evidence of authenticity, and again we find sometimes contradictory reasons in arguing for this case. For the Jungian psychologist Marie-Louise von Franz the authenticity of the dreams was seen in the fact that the images were not exclusively Christian:

Was . . . [die] Echtheit der Visionen anbelangt . . . läßt sich . . . darauf hinweisen, daß in allen Visionen kein einziges rein christliches Motiv auftaucht, sondern lauter archetypische Bilder, die der damaligen heidnischen, gnostischen und christlichen Vorstellungswelt gemeinsam waren . . .[39]

For Shaw “there is no reasonable question of their authenticity”.[40] For Amat, the dreams are “realistic” and therefore they should not be deemed fabricated:

Mais, il faut y insister, des songes véritables, elles ont le syncrétisme et la subjectivité. On peut donc écarter l’hypothèse . . . selon laquelle ces récits seraient des affabulations . . . . Ils portent indéniablement la trace de souvenirs vécus.[41]

Amat refers to Franz’s view but adds, contradicting Franz, that it is their Christian frames of reference that make them, in part, the evidence of their reality. Amat stresses the mix of lived experiences and “de souvenirs littéraires ou scripturaires” that supplant pagan associations:

Mais la culture païenne ne fait qu’affleurer sous son adaptation chrétienne et scripturaire. . . . Les éléments scripturaires sont plus allusifs dans les songes de Perpétue : les details issus de l’Apocalypse s’unissent à l’échelle de Jacob, au serpent de la Genèse ou à l’abîme de l’Évangile de Luc.[42]

It is natural to assume that a Christian martyr would have biblical images on her mind but in favour of Franz’s view is the point that Perpetua was apparently a new convert so it might be fair to question the extent of her biblical knowledge. Does Amat’s Perpetua know the Bible too well? While conflicting explanations do not per se negate authenticity, they invite scrutiny of potential confirmation bias.

In her discussion of the dreams it is difficult to tell if Amat is speaking for the beliefs of the authors and editors of the Passio or for herself and her audience when she writes:

[U]n tel mélange [sc. souvenirs vécus and de souvenirs scripturaires] caractérise les véritables manifestations oniriques. Ce constat n’entame nullement la notion de révélation. L’Esprit passe, pour se faire entendre, par toutes les images qui reposent dans la conscience des songeurs.[43]

If the latter, we can understand the pull of wanting Perpetua’s words to be historically authentic. But motive aside, it is widely understood that realism of description does not necessarily establish authenticity.[44]

One more facet in the study of the Passio that has been used to argue for a female author, and by implication the Perpetua of the diary herself,[45] is the motif of breast-feeding and lactation.

The Passio includes references to breastfeeding from a lactating woman’s point of view; . . . symptoms . . . including anxiety, pain, and engorgement . . .[46]

The references certainly express a “woman’s point of view”, but the question of authenticity of Perpetua’s account is not necessarily tied to the gender of the author. On the other hand, Dova also observes that “there is a wealth of evidence about wet-nursing in Perpetua’s time”, so it is reasonable to expect that some men were quite aware of what it involved. More significant, however, are Perkins and DeVore noting that imagery of nursing mothers and infant feeding was well established in early Christian writings:

[E]mphasis on lactation and parturition . . . are so rhetorically pertinent to the discourse of the period in Carthage as evidenced by Tertullian as to make suspect the women’s authenticity as real persons.[47]

I suspect that, in her references to nourishment and lactation, Perpetua participates far more in common symbolic imagery than in a personally cathartic diurnal divulgence.[48]

For a good number of scholars the Passio is a unique document, a primary source to inform us directly of the mind of a martyr and of a woman in the third century Roman empire,[49] as well as being an inspiration for all, especially for women, as a testimony of courage and independence of spirit.[50] These are strong reasons for wanting an ancient source to be both unique and authentic. Other historians have warned against the professional hazards of being seduced into accepting sources as historically reliable[51] and naively embracing texts at face value.[52]

I have attempted to single out a few areas where scholars take different approaches to reading the Passio. My focus has been on what I consider to be some of the shortcomings underlying an acceptance of Perpetua’s account as “authentic”. I have sought to do this by identifying flawed reasoning, a tendency to find confirmation of authenticity in various textual and independent data without examining alternative explanations for the same data, a failure to address the rhetorical methods that create the emotional impact on reading the Passio, and a limited appeal to the literary context of the early Christian centuries.

Notes

[1] Hunink, “Did Perpetua Write Her Prison Account?,” 150, 152.

[2] Hunink, 150, 152.

[3] Hunink, 150.

[4] Farina, Perpetua of Carthage, 6f.

[5] Amat, Passion de Perpétue et de Félicité suivi des Actes : Introduction, Texte Critique, Traduction Commentaire et Index, 21.

[6] Droge, “The Apologetic Dimensions of the Ecclesiastical History,” 506.

[7] Grant, Eusebius as Church Historian, 165.

[8] Moreau, La Persécution du Christianisme dans L’Empire Romain, 81.

[9] Frend, “A Severan Persecution? Evidence of the « Historia Augusta »,” 470.

[10] Barnes, “Tertullian’s ‘Scorpiace,’” 130.

[11] Kitzler, From Passio Perpetuae to Acta Perpetuae : Recontextualizing a Martyr Story in the Literature of the Early Church, 15, note 59.

[12] Barnes, “Pre-Decian Acta Martyrum,” 509–31.

[13] Muehlberger, “Perpetual Adjustment: The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity and the Entailments of Authenticity,” 323.

[14] Robinson, The Passion of S. Perpetua, 25.

[15] Heffernan, The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity, 76f.

[16] Amat, Passion de Perpétue et de Félicité suivi des Actes : Introduction, Texte Critique, Traduction Commentaire et Index, 20.

[17] Tertullian, “De Anima,” LV 4.

[18] Muehlberger, “Perpetual Adjustment: The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity and the Entailments of Authenticity,” 325–27.

[19] Muehlberger, 333.

[20] Muehlberger, 338.

[21] Butler, The New Prophecy and “New Visions,” 47. Butler sees both Robinson’s and Shewring’s analysis of style as paving the way for the near consensus on authenticity, but Robinson is discussed as the lead figure.

[22] Amat, Passion de Perpétue et de Félicité suivi des Actes : Introduction, Texte Critique, Traduction Commentaire et Index, 35.

[23] Amat, 33.

[24] Muehlberger, “Perpetual Adjustment: The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity and the Entailments of Authenticity,” 324.

[25] Shaw, “The Passion of Perpetua,” 19, 22, 45.

[26] Shaw, 20, note 50.

[27] Heffernan, The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity, 76; DeVore, “Narrative Traditioning and Allusive Gesturing,” 236.

[28] Dodds, Pagan and Christian in an Age of Anxiety, 49f, 52.

[29] Shaw, “The Passion of Perpetua,” 20f.

[30] Dodds, Pagan and Christian in an Age of Anxiety, 49.

[31] Lander and Kraemer, “Perpetua and Felicitas,” 984.

[32] Ronsse, “Rhetoric of Martyrs,” 385.

[33] DeVore, “Narrative Traditioning and Allusive Gesturing,” 36ff.

[34] DeVore, 230–31.

[35] Dodds, Pagan and Christian in an Age of Anxiety, 51.

[36] DeVore, “Narrative Traditioning and Allusive Gesturing,” 147.

[37] Dronke, Women Writers of the Middle Ages: A Critical Study of Texts from Perpetua to Marguerite Porete, 1, 6, 16f.

[38] DeVore, “Narrative Traditioning and Allusive Gesturing,” 172f.

[39] Franz, “Die Passio Perpetuae. Versuch Einer Psychologischen Deutung,” 411.

[40] Shaw, “The Passion of Perpetua,” 26.

[41] Amat, Passion de Perpétue et de Félicité suivi des Actes : Introduction, Texte Critique, Traduction Commentaire et Index, 42.

[42] Amat, 42, 45.

[43] Amat, 42.

[44] Johnson, “Third Maccabees: Historical Fictions and the Shaping of Jewish Identity in the Hellenistic Period,” 196f; Van den Heever, “Novel and Mystery: Discourse, Myth, and Society,” 93f; Woodman, Rhetoric in Classical Historiography: Four Studies, 23–28.

[45] Cotter-Lynch, Saint Perpetua across the Middle Ages, 19.

[46] Dova, “Lactation Cessation and the Realities of Martyrdom in The Passion of Saint Perpetua,” 260.

[47] Perkins, Roman Imperial Identities in the Early Christian Era, 160.

[48] DeVore, “Narrative Traditioning and Allusive Gesturing,” 125.

[49] Rader, “The Martyrdom of Perpetua: A Protest Account of Third-Century Christianity,” 2f; Shaw, “The Passion of Perpetua,” 12f.

[50] Perkins, “The ‘Passion of Perpetua’: A Narrative of Empowerment,” 838.

[51] Finley, Ancient History, 21.

[52] Clines, What Does Eve Do To Help?, 164.

Bibliography

Amat, Jacqueline, ed. Passion de Perpétue et de Félicité suivi des Actes : Introduction, Texte Critique, Traduction Commentaire et Index. Sources Chrétiennes 417. Paris: Editions du Cerf, 1996.

Barnes, Timothy D. “Pre-Decian Acta Martyrum.” The Journal of Theological Studies XIX, no. 2 (1968): 509–31.

———. “Tertullian’s ‘Scorpiace.’” The Journal of Theological Studies 20, no. 1 (1969): 105–32.

Butler, Rex D. The New Prophecy and “New Visions”: Evidence of Montanism in the “Passion of Perpetua and Felicitas.” Patristic Monograph Series 18. Washington (D. C.): Catholic university of America press, 2006.

Clines, David J. A. What Does Eve Do To Help?: And Other Readerly Questions to the Old Testament. Sheffield, England: Bloomsbury T&T Clark, 1990.

Cotter-Lynch, Margaret. Saint Perpetua across the Middle Ages: Mother, Gladiator, Saint. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2016.

DeVore, Megan. “Narrative Traditioning and Allusive Gesturing: Perpetua Reconsidered.” Ph.D., University of Wales Trinity Saint David (United Kingdom), 2015.

Dodds, Eric R. Pagan and Christian in an Age of Anxiety: Some Aspects of Religious Experience from Marcus Aurelius to Constantine. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1965.

Dova, Stamatia. “Lactation Cessation and the Realities of Martyrdom in The Passion of Saint Perpetua.” Illinois Classical Studies 42, no. 1 (April 1, 2017): 245–65.

Droge, Arthur J. “The Apologetic Dimensions of the Ecclesiastical History.” In Eusebius, Christianity, and Judaism, edited by Harold W. Attridge and Gohei Hata, 492–509. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1992.

Dronke, Peter. Women Writers of the Middle Ages: A Critical Study of Texts from Perpetua to Marguerite Porete. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984.

Farina, William. Perpetua of Carthage: Portrait of a Third-Century Martyr. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland, 2008.

Finley, M. I. Ancient History: Evidence and Models. New York: Viking, 1986.

Franz, Marie-Louise von. “Die Passio Perpetuae. Versuch Einer Psychologischen Deutung.” In Aion: Untersuchungen Zur Symbolgeschichte, 387–496. Zürich: Rascher, 1951.

Frend, W. H. C. “A Severan Persecution? Evidence of the « Historia Augusta ».” In Forma Futuri. Studi in Onore Del Cardinale Michele Pellegrino., edited by Michele Pellegrino, 470–80. Torino: Bottega d’Erasmo, 1975.

Grant, Robert M. Eusebius as Church Historian. Oxford : Clarendon Press, 1980.

Heffernan, Thomas J. The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Hunink, Vincent. “Did Perpetua Write Her Prison Account?” Listy Filologické / Folia Philologica 133, no. 1/2 (2010): 147–55.

Johnson, Sara R. “Third Maccabees: Historical Fictions and the Shaping of Jewish Identity in the Hellenistic Period.” In Ancient Fiction. The Matrix of Early Christian and Jewish Narrative, edited by Jo-Ann A. Brant, Charles W. Hedrick, and Chris Shea, 185–97. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2005.

Kitzler, Petr. From Passio Perpetuae to Acta Perpetuae : Recontextualizing a Martyr Story in the Literature of the Early Church. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2015.

Lander, Shira L., and Ross S. Kraemer. “Perpetua and Felicitas.” In The Early Christian World, edited by Philip F. Esler, Second., 976–95. London & New York: Routledge, 2002.

Moreau, Jacques. La Persécution du Christianisme dans L’Empire Romain. 1er Édition/3e Trimestre 1956. Paris: Presses Universitaires De France, 1956.

Muehlberger, Ellen. “Perpetual Adjustment: The Passion of Perpetua and Felicity and the Entailments of Authenticity.” Journal of Early Christian Studies 30, no. 3 (2022): 313–42.

Perkins, Judith. Roman Imperial Identities in the Early Christian Era. London & New York: Routledge, 2008.

———. “The ‘Passion of Perpetua’: A Narrative of Empowerment.” Latomus 53, no. 4 (October 1994): 837–47.

Rader, Rosemary. “The Martyrdom of Perpetua: A Protest Account of Third-Century Christianity.” In A Lost Tradition: Women Writers of the Early Church, edited by Patricia Wilson-Kastner, 1–17. Washington, D.C.: University Press of America, 1981.

Robinson, Joseph Armitage. The Passion of S. Perpetua. Facsimile Reprint. Piscataway, N.J: Gorgia Press, [1891] 2004.

Ronsse, Erin. “Rhetoric of Martyrs: Listening to Saints Perpetua and Felicitas.” Journal of Early Christian Studies 14, no. 3 (September 2006): 283–327.

Shaw, Brent D. “The Passion of Perpetua.” Past and Present 139, no. 1 (1993): 3–45.

Tertullian. “De Anima.” Accessed May 26, 2025. https://www.tertullian.org/latin/de_anima.htm.

Van den Heever, Gerhard. “Novel and Mystery: Discourse, Myth, and Society.” In Ancient Fiction. The Matrix of Early Christian and Jewish Narrative, edited by Jo-Ann A. Brant, Charles W. Hedrick, and Chris Shea, 89–114. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2005.

Woodman, A. J. Rhetoric in Classical Historiography: Four Studies. London : New York: Routledge, 2004.