The Greek Mythicists website has posted a (Greek language) interview with Thomas L. Thompson. The interview page is Συνέντευξη με τον Thomas L. Thompson: Ο Βιβλικός Μινιμαλισμός και ο ιστορικός Ιησούς. The person responsible for the site, Minas Papageorgiou, has kindly sent me an English translation. It is very lengthy so I will only post one part of it for now. More to follow. Thanks to Minas Papageorgiou/Μηνάς Παπαγεωργίου.

The Greek Mythicists website has posted a (Greek language) interview with Thomas L. Thompson. The interview page is Συνέντευξη με τον Thomas L. Thompson: Ο Βιβλικός Μινιμαλισμός και ο ιστορικός Ιησούς. The person responsible for the site, Minas Papageorgiou, has kindly sent me an English translation. It is very lengthy so I will only post one part of it for now. More to follow. Thanks to Minas Papageorgiou/Μηνάς Παπαγεωργίου.

(For background: The Vridar blog is not a “Jesus mythicist” blog even though it is open to a critical discussion of the question of Jesus’ historicity. I do not see secure grounds for believing in the historicity of Jesus but it does not follow that I reject Jesus’ historicity. Clearly, the Jesus of the Gospels and Paul’s letters is a literary and theological construct but it does not follow that there was no “historical Jesus”. Nor do I endorse all views that I have seen associated with Greek Mythicists, though I have been included in one of their publications: see Jesus Mythicism: An Introduction by Minas Papageorgiou and To the Greeks, Vridar in a Greek publication)

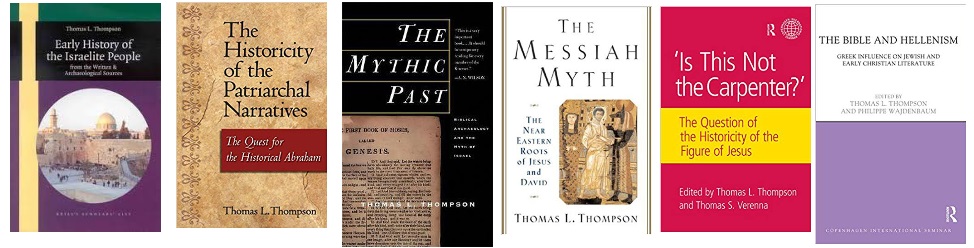

Who is Thomas L. Thompson? If you only have the vaguest idea or none at all see my notes at the end of this post. His works have certainly influenced me greatly.

The English language version of the interview, part 1 . . . .

1) Υοu spent a big part of your life in Tübingen, Germany. Would you agree that you were touched by Bruno Bauer‘s aura?

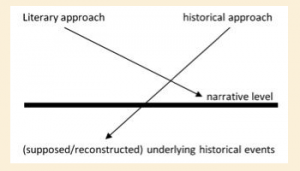

Bauer was much more influential in Berlin and Bonn than Tübingen, where in New Testament studies, Ernst Käsemann drew far more in the direction of establishing and defending an historical Jesus, much in the spirit of the “Jesus Seminar” in the States. In Old Testament studies and Palestinian archaeology, which were my primary interests, the tradition rather lay in comparative literature and comparative religions. Kurt Galling, editor of the great 5 volume, German encyclopedia of religion (Religion in History and the Present 1935) was my professor. He was a student of Hugo Gressmann and Hermann Gunkel and held history and archaeology separate from literature and theology and the study of the Bible was, first of all, a literary work rather than history!

2) In Greece, it is rather impossible to see an academic theologian holding a critical stance towards the Bible. Are things different in the rest of the world?

Greek orthodoxy sees the role of theology as explanatory and Greek theology—much like Roman Catholicism is often very defensive of traditional teaching, except that Greek theology tries to idealize the theology of the early church fathers, while Catholicism looks to the theology of Aquinas and the European Middle Ages as the ideal. But they are both rapidly changing today and one finds a few sound, critical scholars in Greece today and an even greater number of them among Roman Catholic scholars. I think the most influential of conservative scholars are the fundamentalists in the US, where the Bible seems to be read as a description of actual events in which God was the primary active figure. Critical scholarship, which starts from the observation that biblical narrative is first of all literature and needs to be treated as such. It is strongest in Europe, where a strong commitment to critical humanism is the norm for most universities: especially in Germany and Denmark. Perhaps it is best to think of individual scholars and universities rather than countries. The university of Rome, Göttingen, Tübingen, Sheffield and Copenhagen insist that biblical studies be critical rather than traditional.

3) Explain to us in a few words what biblical minimalism is, who the scholars that comprised the core of its existence were and what was your part in this.

Biblical minimalism grows out of the failure of biblical archaeology’s efforts to provide a critical history of Israel. It is important to point out that “minimalism” is a term which was used by opponents of critical biblical scholarship. It was not a self-description. The development in critical biblical studies, which came to reject the use of the Biblical narrative as a historical description of past events was called “minimalism” because these scholars did not share the assumption of, for example, biblical archaeologists, that history could be written by bringing together evidence from biblical narrative and our knowledge of ancient history. Minimalists saw the Bible as allegorical literature and consequently separated their use of archaeology from the Bible to write their history of Palestine. Indeed, understanding history of the South Levant as a regional history of Palestine, rather than as an ethnocentric history of the people of Israel allowed us to understand the Bible’s literary narrative of Israel as a fictional and theological product: what I came to refer to as a “mythic past.” In contrast, our history (of Palestine) is evidence-based in archaeology and contemporary inscriptions rather than biblical narrative, as in biblical archaeology. Continue reading “Interview with Thomas L. Thompson #1”