The previous post concluded thus:

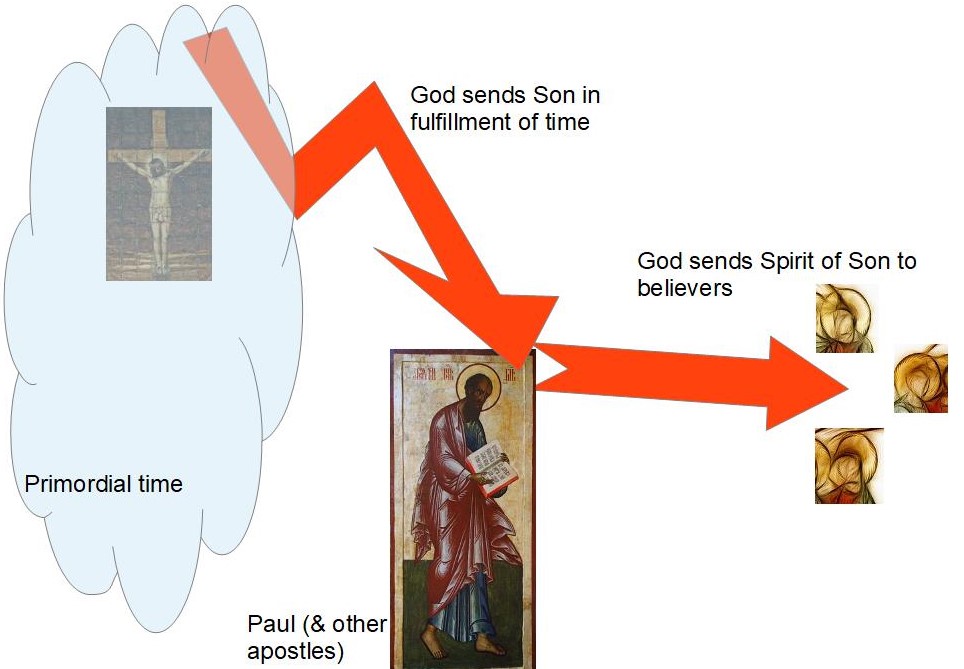

As I mentioned at the beginning of this post, my revised hypothesis basically adds only two things to Loisy’s scenario: (1) I would identify the above “Christian groups which believed themselves heirs of the Pauline tradition” as Saturnilians. (2) I would identify the above “mystery of salvation by mystic union with a Saviour who had come down from heaven and returned to it in glory” as the Vision of Isaiah. I also said, earlier in this post, that my recognition of the role the Vision plays in the Pauline letters had changed my perspective on a number of early Christian issues. Before closing I would like to say a few things about perhaps the most significant of them: the historicity of Jesus.

Continuing and concluding the series ….

…

Historical Jesus?

I am now much more open to the possibility that the version of the Vision used by Paul’s interpolators included the so-called “pocket gospel.” The Jesus of that gospel is docetic. He only appears to be a man. Such a Jesus could explain curious Pauline passages such as this one:

Thus it is written: There was made the first man, Adam, living soul; the last Adam lifegiving spirit. But the spiritual is not first, the first is the living, then the spiritual. The first man, being of earth, is earthy, the second man is of heaven. As is the earthy, so too are the earthy. As is the heavenly, so too are the heavenly. And as we have borne the likeness of the earthy, we shall bear the likeness of the heavenly… (1 Cor. 15, 45-49)

Commentators say that we have to understand here a resurrected Christ as the second man; that Christ too was first earthy, and became lifegiving spirit by his resurrection. But notice that the resurrection is not mentioned in the passage. And it doesn’t mention a transformation for Christ from earthy to spiritual. We are the ones who are said to be in need of transformation.

Commentators say that we have to understand here a resurrected Christ as the second man; that Christ too was first earthy, and became lifegiving spirit by his resurrection. But notice that the resurrection is not mentioned in the passage. And it doesn’t mention a transformation for Christ from earthy to spiritual. We are the ones who are said to be in need of transformation.

Moving on: In the pocket gospel there is not a real birth. As Enrico Norelli explains it:

If the story is read literally, it is not about a birth. It’s about two parallel processes: the womb of Mary, that had enlarged, instantly returned to its prior state, and at the same time a baby appears before her— but, as far as can be determined, without any cause and effect relationship between the two events. (Ascension du prophète Isaïe, pp. 52-53, my translation)

This could explain why, in Gal. 4:4, Jesus is “come of a woman, come under the Law.” The use of the word γενόμενον [genômenon] (to be made/to become) instead of the far more typical γεννάω [gennâô] (to be born) could signal a docetic birth. The Jesus of the Vision comes by way of woman—and since she was Jewish, he thereby came under the Law—but he was not really born of her.

And, in general, with the pocket gospel as background the interpretation of the crucifixion by “the rulers of this world” in 1 Cor. 2:8 ceases to be an issue. Likewise the improbable silences in the Pauline letters. We can account for why, apart from the crucifixion and resurrection, there is practically nothing in the Paulines about what Jesus did or taught. For the Jesus of the pocket gospel is not presented as a teacher. Not a single teaching is put in his mouth. He is not even any kind of a leader. He is not said to have gathered disciples during his lifetime. All we get is this:

And when he had grown up, he performed great signs and miracles in the land of Israel and Jerusalem. (Asc. Is. 11:18)

These “signs and miracles” need be no more than the kind of bizarre things that, according to the pocket gospel, accompanied his so-called birth. They would be like the curious coincidences that happen to people all the time. But in his case they took on added significance once someone had a vision of him resurrected from the dead. “Hey, I remember once he put his hand on Peter’s mother-in-law when she was sick, and it was weird the way she seemed to get better right away.”

In other words, I think the pocket gospel may actually give us an earlier and more accurate look than the canonical gospels at what a historical Jesus could have been like. He was not a teacher or even a leader of any kind. If he went up to Jerusalem with some fellow believers in an imminent Kingdom of God—perhaps a group of John the Baptist’s followers—he was not the leader of the group. Once in Jerusalem he may have done or said something that got him pulled out from the others and crucified. That would have been the end of the story. Except that another member of the group had a vision of him resurrected, and interpreted it as meaning that the Kingdom of God was closer than ever. Jesus thereby began to take on an importance all out of proportion with his real status as a nobody. The accretions began. And the excuses for why no one had taken much notice of him before.

Why Jesus? Why not a vision of a more significant member of the group? Why not a vision of a resurrected John the Baptist? I don’t know. Maybe John was still alive at the time. Maybe Jesus just happened to be the first member of the group to meet a violent end. Hard to know.

And I’m not sure whether, according to Bayesian analysis, such a further reduction of Jesus increases or decreases the probability of his historical existence. But it does seem to me that such an extremely minimal Jesus can reasonably fit the kind of indications present in the Pauline letters. So sadly, I find I must change my affiliation from Mythicist to Agnostic (but leaning Historical).