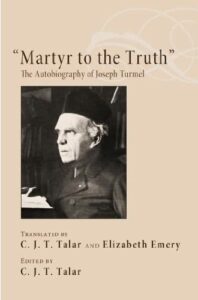

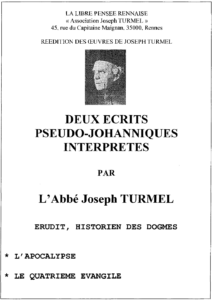

Before Thomas Witulski’s 2012 book (link is to posts discussing W’s work) that identified the two witnesses of Revelation with figures in the Bar Kochba War there was Joseph Turmel’s 1938 publication, which made the same fundamental point but by a different route. You can read his case from the link in my Turmel page and/or you can read some key points in what follows here.

Before Thomas Witulski’s 2012 book (link is to posts discussing W’s work) that identified the two witnesses of Revelation with figures in the Bar Kochba War there was Joseph Turmel’s 1938 publication, which made the same fundamental point but by a different route. You can read his case from the link in my Turmel page and/or you can read some key points in what follows here.

Turmel set out the two most commonly expressed options for the date of the Book of Revelation (Apocalypse) —

- from soon after the time of Nero’s death, say 69 CE

- the late first century around the time of Domitian

Turmel eliminates the first option because it lacks motivation: the idea of a returned Nero to destroy Rome was inspired by popular rumours in the wake of a Nero-imposter who, no later than February 69 CE, came not from the Euphrates River and was slain before he reached Rome; such a figure cannot explain the details we read in Revelation.

A second Nero-imposter did appear in the year 88, this time from beyond the Euphrates (as per Revelation). So the time of Domitian is more likely, but given that the popular anticipation of a return by Nero continued through to the time of Augustine, Revelation could also have been written a good while after Domitian.

Revelation depicts God’s vengeance befalling the planet as a result of the cries of the recently slain martyrs. (Whether those martyrs are Jewish or Christian remains open at this point.) There were three periods of mass martyrdoms:

- Nero’s purported persecutions (64 CE),

- the widespread massacres in Trajan’s time (ca 117 CE)

- and the Bar Kochba war of 132-135 CE.

Turmel has ruled out #1; he rules out #2 on the grounds that it did not take place in Palestine or Jerusalem — as indicated in Revelation; so that leaves #3.

Are the martyrs Christians?

No, concludes Turmel, because their blood is linked to the blood of the prophets before them. The martyrs belong to the prophets. They are the Judeans.

This conclusion is confirmed by the conclusion of Revelation where the New Jerusalem descends to the place where the old Jerusalem was once situated and the twelve gates bore the names of the twelve tribes of Israel. Yes, we also read that the foundation stones were twelve in number and that the names of the apostles were inscribed on them, but how could such a large city said to be a square shape have twelve bases? No, that detail is a later addition to try to Christianize a Jewish Apocalypse.

Turmel refers to the evidence we later find in Jewish writings to depict Bar Kochba as a self-proclaimed Messiah and his promoter, the rabbi Akiba, as comparable to Ezra or Moses. These two men led a revolt that lasted around three years (132-135), thus easily inviting a Danielic reference to 1260 days / three and a half years for the time of the two witnesses. Bar Kochba was famous for being able to literally perform the magician’s trick of breathing fire from his mouth. He had coins minted with the image of the temple beneath a purported star — suggesting that he had hastily built a new temple (the star was a reference to his name and the prophecy in Numbers).

Some of those details have been disputed (successfully, I think) in more recent publications. For example, the later idea that Bar Kochba claimed to be the messiah is not supported by the earlier evidence. But see the Witulski posts for details.

Turmel and Witulski otherwise have very different readings:

Turmel — Revelation is principally a Jewish work that was supplemented with Christianizing edits; the dragon who sweeps a third of the stars down from heaven is understood to be a Christian monster leading many Judeans astray, for example.

Witulski — Revelation is principally a Christian work that focussed primarily on Hadrian and his propagandist Polemo.

Both agree on identifying Bar Kochba as one of the two witnesses. (Witulski replaces Turmel’s Akiba with the high priest Elazar.)

What I liked about Turmel’s discussion was his explanation for the site of Jerusalem being called Sodom and Egypt: Hadrian had replaced the site with his new capital Aelia Capitolina (dedicated to Jupiter). That’s why a New Jerusalem was to descend and take its place.

What I find difficult to accept in Turmel’s discussion is that a Christian editor might leave untouched the original Jewish account of the two witnesses being taken up to heaven in the sight of all if he so hated them because of their persecutions of Christians. I think Witulski’s explanation that that image was a future projection at the time of writing is preferable. (W also sees the Christian author having anti-Pauline and pro-Jewish sympathies.)