Let us now turn to a famous story found in the Babylonian Talmud, b. Taanit 5b. While sitting together at a meal Rav Nahman asked Rabbi Yitzhaq to expound on some subject. After some preliminary diversions, Rabbi Yitzhaq said in the name of Rabbi Yohanan, “Our father Jacob never died.”

Rav Nahman was taken aback by this claim and said, “But he was embalmed and buried.” How is possible to do such things to someone who has not died?

Rabbi Yitzhaq responds and says, . . . . “I am engaged in Bible elucidation,” and he then cites Jer 30:10, “Therefore fear not, my servant Jacob, says the LORD; be not dismayed, Israel, for I will save you from afar and your seed from the land of their captivity.” He continues, “Israel is compared to his seed; just as his seed is alive so too is he alive.”

At first sight, it appears that the midrashic statement denying Jacob’s death is being derived from Jer 30:10. However, if we look closer at the passage, we will find a fascinating distinction between the biblical deathbed scenes of Abraham (Gen 25:8) and Isaac (35:29), on the one hand, and that of Jacob (49:33), on the other. In the former scenes, two verbs, . . . “expired,” and . . . “died,” and one phrase, . . . “was gathered to his people,” are used to describe their deaths. Regarding Jacob, however, only two verbs appear: expiring and being gathered to his people. For the midrashist, the absence of any verb from the root . . . “to die”, in the description of Jacob’s death cannot be by chance, but must be understood as communicating to us the Bible’s message that Jacob did not die.

According to the story, Rabbi Yitzhak’s statement to Rav Nahman was made in a completely neutral context — that is, outside of any context whatsoever. Consequently, Rav Nahman understood this claim as being functionally parallel to a claim such as “Elijah did not die.” The characteristic position of rabbinic Judaism is, of course, that Elijah never died but is still alive; indeed, according to the rabbis, he is the heavenly recorder of human deeds. Rav Nahman therefore asked Rabbi Yitzhak: But Jacob was embalmed and buried, so how can you claim he did not die. Rabbi Yitzhak’s response, . . . . “I am engaged in Bible elucidation,” and the citation of Jer 30:10, is not given to tell us the source of his previous statement, for as we have just seen, its source is the absence of any mention of death in Jacob’s deathbed scene. What he is doing is saying the following:

“You have misunderstood me; my statement that Jacob did not die is not to be understood as a literal-historical depiction of historical facts, but as midrash.”

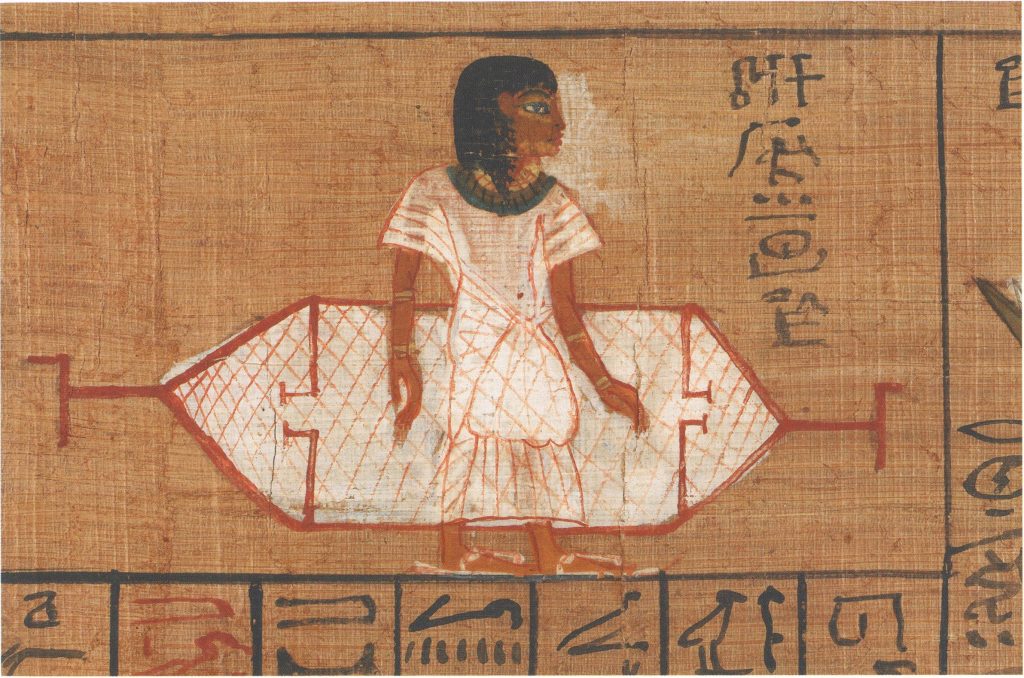

Midrash comes to tell us a story placed in the biblical text by God, having no necessary relationship to the actual historical events, but whose purpose is to give us a message from God. That message is being explained to Rav Nahman by Rabbi Yitzhaq’s citation of Jeremiah. God’s exclusion of any mention of Jacob’s death is a promise found midrashically in Genesis and explicitly in Jeremiah: for Rabbi Yitzhaq, Jacob’s nondeath is a promise that his seed shall exist forever.

This midrash and its surrounding narrative are important because they give what we desperately need in reading midrash: a cultural and theoretical context. The original misunderstanding by Rav Nahman and the final exposition by Rabbi Yitzhak show, as clearly as possible, that midrashic narrative is explicitly demarcated from the historical-literal reconstruction of past events. Midrash is the rabbis’ reconstruction of God’s word to the Jewish people and not the rabbis’ reconstruction of what happened in the biblical past.

(Milikowsky, pp. 124 f.)

The Bible’s stories are never questioned. They are always bed-rock “true history”.

But the rabbis added stories to those Bible events that are clearly not factual, but nonetheless meaningful and explantory.

Why should the rabbis develop a mode of discourse that tells the truth by means of fictional events, when the only literature they have in front of them is the Bible, which tells the truth by means of true historical events?

For the answer to that question Milikowsky finds a significant discussion on the importance of “good fiction” in Plato’s Republic. At this point, return to the previous post: Why the rabbis . . .

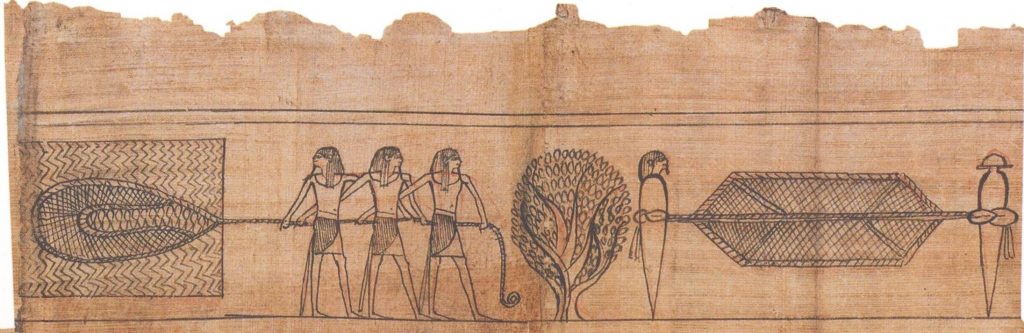

Now what we see in the Gospel of Mark at one level looks like midrashic narrative. For example, we have quotations from Malachi mixed with quotations from Isaiah and Exodus. In the opening scene we have re-enactments of a “man of god” spending time in the wilderness and returning to call out a certain people and performing miracles. It is all familiar to anyone familiar with the Old Testament narratives.

So what is going on here? The question inevitably arises: Does the author of the earliest gospel expect hearers to believe the story as genuine history or as a “message from God” which the Bible texts assert to be “valid” or “true” without necessarily being “historically true”? If the latter, it is surely easy to see why it would be understood and accepted as true on both levels: as a message from God and as genuine history.

Milikowsky, Chaim. 2005. “Midrash as Fiction and Midrash as History: What Did the Rabbis Mean?” In Ancient Fiction: The Matrix of Early Christian And Jewish Narrative, edited by et al Jo-Ann A. Brant, Charles W. Hedrick, and Chris Shea, 117–27. Symposium Series 32. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.