My title refers to the anonymous texts in both the Old and New Testaments and why among those anonymous works we encounter numerous contradictions, even within the same works.

I came across one of the clearest explanations to this question in David’s Secret Demons by Baruch Halpern. Halpern explains why “Near Eastern” writing is so different from Greek writing.

No historical text, and no myth, in the ancient Near East is said to have an author. The first authors of biblical texts are the prophets: Amos, Hosea, then Hezekiah’s prophets, in 701, Micah and Isaiah. In these cases; the texts are attributed to individuals for purposes of establishing the texts’ authority. Amos and Hosea, in particular, can be cited as having personally predicted the fall of Israel. Micah and Isaiah can be said to have foreseen the Assyrian devastation of Judah. But in Mesopotamia, textual composition is so anonymous that even astronomical advances have no authors, although the Greeks were able to name particular Babylonians who invented techniques of analysis. Likewise, in Israel, historiographic texts are purely anonymous.

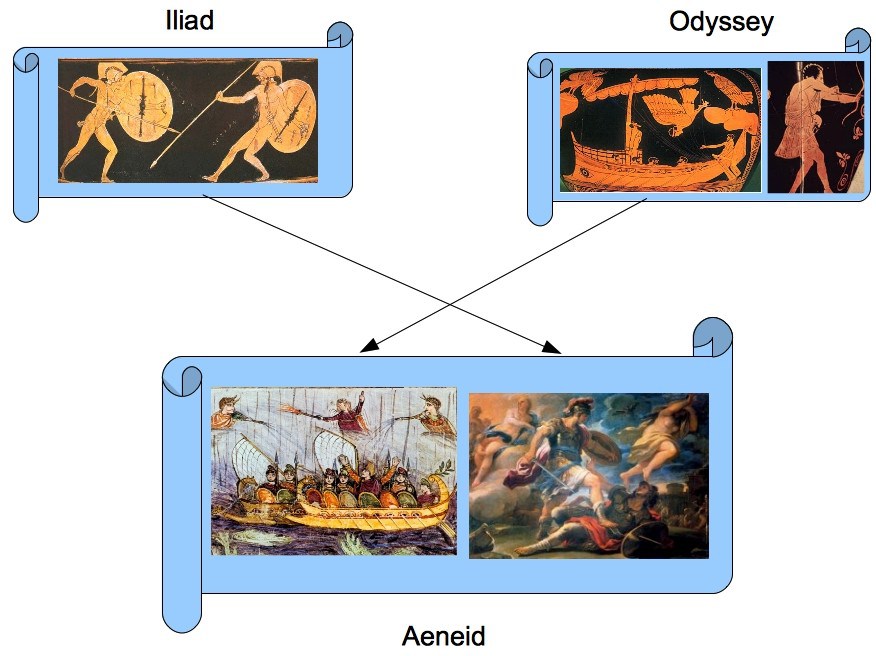

The inverse is true in Greece. Starting with Homer, we have virtually no texts without a personal ascription. Philosophical works, poetic works, and historical works are all attributed to specific authors. Why the contrast? What is the difference between Greek and Near Eastern authorship or composition? Essentially, Greek texts are all open to public dispute. They are unambiguously partisan, and unambiguously controvertible as a result. From the start, authors attack Homer. Philosophers attack their contemporaries and predecessors. There is no hint that the revision of earlier thought is a private matter, inside of a collective tradition. The conflicts are individual and open.

Near Eastern texts, by way of contrast, are composed by a collective establishment. That authors are not identified is one signal. Another is that Near Eastern myths and historical texts correct antecedent texts without explicitly referring to them. Thus, Gen. 1, the creation story in which Israel’s God is infallible, corrects Gen. 2-3, in which Yahweh, creating humans, errs: it is not good that the man should be by himself, for example; or, having determined to make a mate for the man, Yahweh fails to reproduce him from the clay, and engenders animals instead in error. There is no reference in Gen. 1 to Gen. 2-3. Instead, the correction is quiet, indirect. (Halpern 129)

Why?

Halpern begins to explain

The adjustments, in the Near East, occur within a tradition. The unity of the tradition is unquestioned. . . .

Halpern even compares the Mesopotamian debates over myths and history with the way discussions today take place “within the traditions of Catholicism and of Orthodox Judaism”:

The elite has a sense of collaboration, a sense of collective identity. (130)

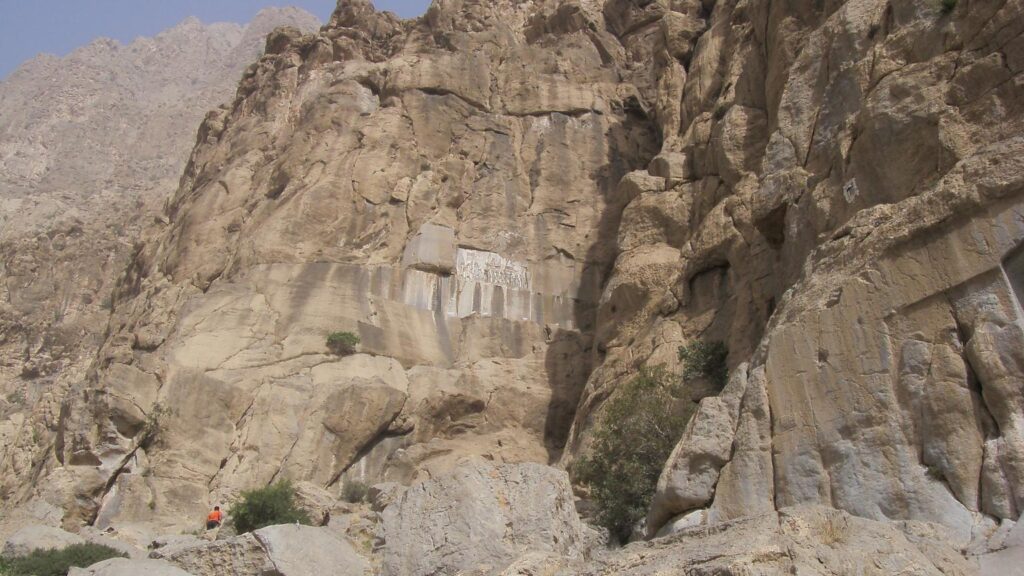

And the result is profound — especially in a culture where illiteracy rates are low. Some scholars have raised the question of whether certain imperial inscriptions were ever meant to be read by the public given that they are so inaccessible. The Behistun monument, for example.

Halpern answers that it would make no difference if the inscription were plastered on roadside billboards. It would make no difference to a wider community who could not read.

But their propagandistic aims indicate that the texts were indeed disseminated. The audiences that kings targeted were, at a minimum, the officialdom and army, but even more probably the citizenry of major communities. The texts must have been read or summarized at public events, and this informal means of dissemination may have been more effective than writing. That is, the outsider audience was almost wholly illiterate, while the insider audience had a higher literacy rate. (129)

So we have an elite literate group with a collective identity and knowing the codes and formulas of writing each kind of genre on the one hand, and an outside audience on the other.

Halpern is describing how a particular inscription of an Assyrian king boasting great conquests in fact, on close reading and decoding the literary play at work, conceals a quite different picture: a partial conquest of several places, ephemeral raids on others, and total conquest of but very few.

On the one hand, general audiences heard the inscriptions. Texts describing the king’s accomplishments are primarily directed externally — the unlettered reader will take the claims of the text at face value. For such readers, the conquest of 42 lands is understood to mean the enduring subjugation of 42 complete and independent political authorities. (130)

Meanwhile,

On the other hand, the expectation is that the insider audience, the elite, will analyze the language in detail. The insiders understood the conventions used to amplify achievement. The reason was, army officers and administrative officials knew how foreign relations stood, where the borders were, at the military and at the diplomatic level. Egregious falsification would leave the disgruntled placed to ridicule the king. So the spin, or rhetorical exaggeration, had to be applied within a framework of linguistic conventions that insiders understood and accepted. In other words, members of the elite had to understand how to discount the spin. And once they knew how to do so, they could be expected, unlike David …, but like Solomon threatening to cleave a baby in half, to see through the embellishments of others. (130)

Halpern invites us to imagine authors who were actively composing revisions to existing texts being impressed by, even applauding, the cleverness of the scribes whose work they were in critical dialogue with.

From Halpern’s discussion I imagine that the authors identified themselves as part of a community engaged in dialogue, debates, revisionist views, and so forth, with colleagues, peers, and literary rivals.

In sum, all Near Eastern royal literature is written for a bifurcated audience: the contrast in audiences is that of insider to outsider. (131)

Halpern’s discussion is primarily about historical writing but he opened the discussion to include myth. The modus operandi applies to most literature.

Understanding the gospels?

The title of this post includes the New Testament writings. Halpern was the one who opened the door to their inclusion in this literary tradition.

For a lucid articulation of the application of the same principle to the New Testament by David Friedrich Strauss starting in the 1830s, see Roy A. Harrisville and Walter Sundberg, The Bible in Modern Culture: Theology and Historical-Critical Method from Spinoza to Kasemann (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1995), 96-110. Note that the genre of apocalyptic literature is the ultimate reduction of the principle of insider::outsider literary orientation, excluding the outsider almost totally. (131)

Be warned, though. Harrisville and Sundberg expect the reader to be able to grasp a few of Hegel’s esoteric thoughts. Hegel was at the heart of many of the scholarly debates involving Strauss in his day.

Understanding scribes behind the gospels in this way explains much, I suggest. We can see how Mark’s narrative was rewritten so sharply by later evangelists who evidently had no interest in our understanding of historical fact and who clearly saw “midrashic” type rewriting as belonging to traditions that fluctuated between authoritative and debatable. The outsiders would hear and understand the stories literally while the insiders who knew the conventions knew very well what they were doing.

Affect on Hellenistic dating of the OT?

I’ll add a postscript on how this relates to the Hellenistic hypothesis for the OT.

By comparing motifs in the accounts of David and Solomon with Mesopotamian royal propaganda Halpern finds “an argument for dating the biblical texts.” The narrative of Solomon’s spendour is compared with Assyrian inscriptions:

Late Middle and early Neo-Assyrian royal historiography also manifests a special concern with aggregated totals of horses and chariots the king accumulates. Tiglath-Pileser I relates that he brought the numbers of chariots in Assyria’s service to a new high point, that he annexed land and population, giving the people contentment by satisfying their material needs. . . .

[I]in Shalmaneser III’s Year 22 annals, a typical text is as follows:

I directed plows in the lands of my country. Grain and fodder I made more plentiful than before, I poured out. Yoked horse teams of 2002 chariots and 5542 cavalrymen I attached to the forces of my country. . . .

. . . This sort of summary seems to be absent in later royal inscriptions. The capture of horses and chariots is related instead in reports of individual campaigns.

This theme is articulated concerning Solomon. His trade in horses is attested in 1 Kgs. 4:26(5:6); 10:25-29. And Tiglath-Pileser’s and his successors’ concern with agriculture, prosperity, and contentment is another theme shared with 1 Kgs. 3-10. The motif of satiety is common in Semitic royal inscriptions. Another shared motif is that of the feast, prominent both in the account of Solomon’s temple dedication and in the report of the dedication of Calah by Assurnasirpal II. We have already had occasion to mention the dedicatory feast in connection with David’s installation of the ark in Jerusalem.

These motifs did not disappear after the 11th century: they climax in one sense in the inscriptions of Assurnasirpal II. But inscriptions of the 10th and early 9th centuries no longer showcase them or bundle them together as earlier texts do. Thus, the theme of plenty recurs in inscriptions especially of Assurbanipal but even of Esarhaddon. But the rest of the Middle Assyrian complex is missing. Nor does the issue of prosperity occupy the key place it does in Middle Assyrian texts, even in the Aramaic inscriptions of the 9th and 8th centuries.

All these motifs are largely absent from accounts of biblical kings later than Solomon. It looks as though the royal ideal, particularly of the king as naturalist, reflected in 1 Kgs. 3 10 stems squarely from the late Middle and early Neo- Assyrian milieu.

(120ff)

There it is. Internal textual comparisons date the description of Solomon’s reign to the time of the Neo Assyrian empire. So Halpern quite reasonably concludes. But readers of my recent posts will know there is something missing. It is the wider comparison with Greek historiography. If all we had were a narrative about Solomon’s greatness alone then Halpern’s conclusion could be the final word. But when we read about Solomon’s acquisitions and the beneficence of his reign as it is embedded in a larger narrative of the Primary History (Genesis to 2 Kings), and against the testimony of archaeology that allows credence no room for the biblical description, we have a right to conclude that the biblical narrative draws upon a source contemporary with the Neo Assyrian empire. That is, a source later than the biblical Solomon’s reign but certainly long prior to the Persian era.

In Russell Gmirkin’s view, Halpern’s date should be assigned to the source used by the author of the Solomon tale. See “Solomon’s (Shalmaneser III) and the Emergence of Judah as an Independent Kingdom”

But even Halpern cannot avoid the Greek connection:

Later, in Chronicles, written in the 5th century, Solomon is far less a natural philosopher. Yet the ideal of the king as natural philosopher is also preserved for the 10th century in Tyrian annals reported by Menander of Ephesus. The source alleged that Hiram, contemporary mainly with Solomon, exchanged riddles and proverbs with Solomon; this tradition is elaborated in Dius,52 with a distinctly pro-Tyrian twist.

Halpern, Baruch. David’s Secret Demons: Messiah, Murderer, Traitor, King. Grand Rapids, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans, 2001.

Gmirkin, Russell. “Solomon’s (Shalmaneser III) and the Emergence of Judah as an Independent Kingdom.” In Biblical Narratives, Archaeology and Historicity: Essays In Honour of Thomas L. Thompson, edited by Lukasz Niesiolowski-Spanò and Emanuel Pfoh, 76–90. Library of Hebrew Bible / Old Testament Studies. New York: T&T Clark, 2020. — see https://www.academia.edu/41548182/_Solomon_Shalmaneser_III_and_the_Emergence_of_Judah_as_an_Independent_Kingdom_

Other posts comparing Greek and Mesopotamian methods of introducing contradictory accounts into a single narrative:

- https://vridar.org/2020/12/30/rewritings-and-composite-contradictions-the-way-of-the-bible-from-genesis-to-revelation/

- https://vridar.org/2012/02/10/explaining-the-contradictory-genesis-accounts-of-the-creation-of-adam-and-eve/

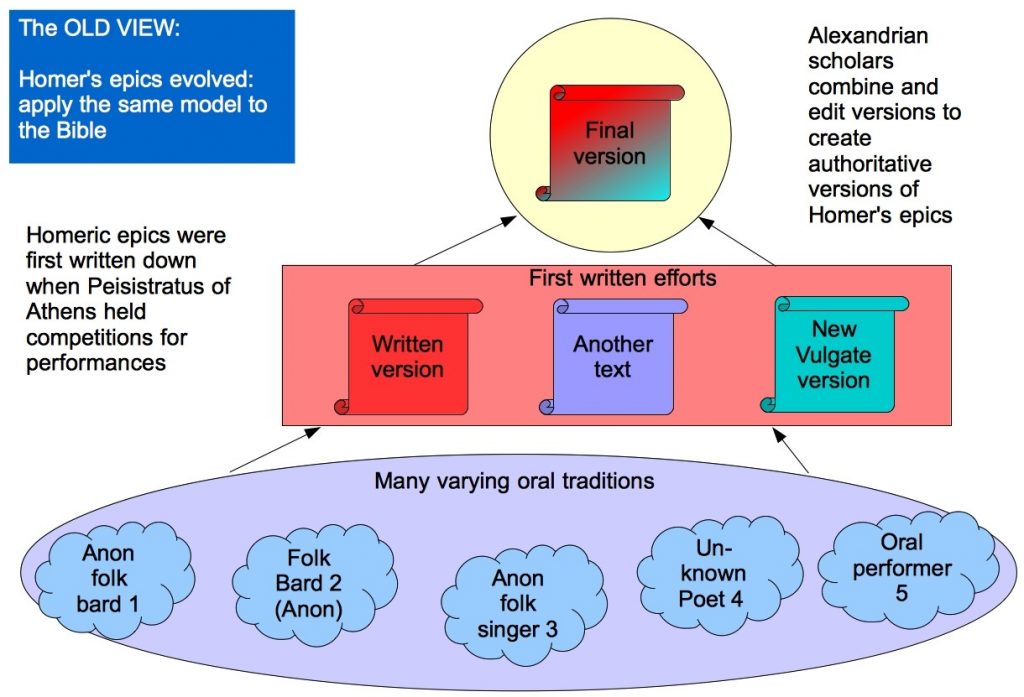

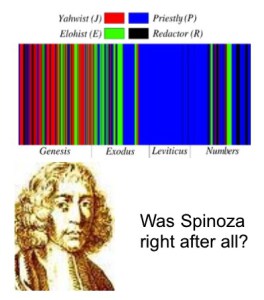

Compare the outcome of criticisms of the Documentary Hypothesis — the thesis that the Old Testament books can be pulled apart into different sources or strata — Priestly, Jahwist, Elohist and Deuteronomist (and a later Redactor).

Compare the outcome of criticisms of the Documentary Hypothesis — the thesis that the Old Testament books can be pulled apart into different sources or strata — Priestly, Jahwist, Elohist and Deuteronomist (and a later Redactor).