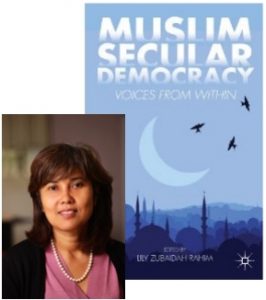

This morning there was a radio interview with Associate Professor Lily Zubaidah Rahim of the University of Sydney about her new book, Muslim Secular Democracy: Voices from within. You can listen to the interview or download it (it’s only a few minutes) from this RN page here. Where I depart from the interview itself I use grey font.

In sum, Lily Rahim argues the significance of the five most populous Muslim nations — India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Egypt and Bangladesh — thriving in either full or hybrid democratic state.

Most Muslim majority states today were originally conceived as secular or quasi secular democracies. But since the mid twentieth century many of these states have moved closer to the Islamic state paradigm — that is, with the onset of Islamization and political Islam that swept through the Muslim world in the wake of the Iranian Revolution in 1979.

A return to the Caliphate?

The interviewer asks if it is not a fact that the Caliphate, the union of religion and the state, that is at the heart of Islam.

Rahim argues (along with other scholars, including Muslim scholars) that the “Islamic State” is really a modern-day twentieth century construct and that the seventh century Caliphate was a phenomenon unique to that period. The Caliphate thus cannot be repeated. The Islamic states that have arisen in more recent times are not replications of the Caliphate. Rather, they are modern attempts to legitimize ruling elites.