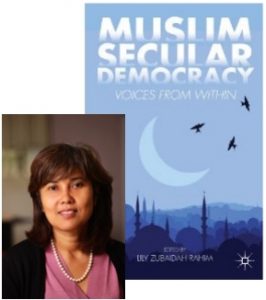

This morning there was a radio interview with Associate Professor Lily Zubaidah Rahim of the University of Sydney about her new book, Muslim Secular Democracy: Voices from within. You can listen to the interview or download it (it’s only a few minutes) from this RN page here. Where I depart from the interview itself I use grey font.

In sum, Lily Rahim argues the significance of the five most populous Muslim nations — India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Egypt and Bangladesh — thriving in either full or hybrid democratic state.

Most Muslim majority states today were originally conceived as secular or quasi secular democracies. But since the mid twentieth century many of these states have moved closer to the Islamic state paradigm — that is, with the onset of Islamization and political Islam that swept through the Muslim world in the wake of the Iranian Revolution in 1979.

A return to the Caliphate?

The interviewer asks if it is not a fact that the Caliphate, the union of religion and the state, that is at the heart of Islam.

Rahim argues (along with other scholars, including Muslim scholars) that the “Islamic State” is really a modern-day twentieth century construct and that the seventh century Caliphate was a phenomenon unique to that period. The Caliphate thus cannot be repeated. The Islamic states that have arisen in more recent times are not replications of the Caliphate. Rather, they are modern attempts to legitimize ruling elites.

Failure of theocratic and secular autocracies

Today it is becoming increasingly clear that experiments with Islamic states have been failures in promoting citizenship rights, modern dynamic economies, social justice, democratic rights. Obvious cases: Saudi Arabia, Iran, Sudan . . . .

Yet neighboring these countries we have others ruled by secular autocrats (their states are not run as Islamic states) where the human rights situations are as bad or worse: Saddam’s Iraq, the Shah’s Iran, Syria.

Rahim argues that today Muslims are increasingly and overtly rejecting both authoritarian Islamic states and authoritarian secular states. The Arab uprising was the most obvious illustration of this. This is also borne 0ut in many surveys such as those of the Gallup Poll and Pew Attitudes Survey and the World Values Survey. All these surveys show that Muslims reject the various forms of authoritarian rule.

The Middle Path — Wasatia

What we find in the studies is the yearning among Muslims for a middle way — “Wasatia/Wasatiyyah Democracy”. (See, for example, Wasatia, Al-Wasatiyyah – The Lost Middle Path, Wasatiyyah -The Balanced Median)

Muslims are not supportive of neither theocracy nor “the assertive secular state” such as that of France (Laïcité) or Turkey (though Turkey has moderated recently with the AKP government) where religion is not permitted in the public sphere.

The interviewer summarizes the sum of Rahim’s argument as:

Muslims in France don’t like being told they cannot wear a hijab and Muslims in Iran don’t like being told they must wear a hijab.

It is this compulsion that is rejected by many Muslims.

Why the Muslim Brotherhood has emerged ahead from the Arab Spring

Yet in the recent elections in Egypt we have the Muslim Brotherhood winning electoral success. Rahim finds that this is another example of where many Islamist parties achieve political success after a prolonged period of authoritarian rule. Rahim sees this as the result of such groups like the Brotherhood having established very strong roots and networks within the local communities during that period and they have been able to draw upon these community roots when running for elections.

Certainly Islamist groups like the Brotherhood did not initiate the Arab uprising, but they benefitted from the ousting of the autocratic Mubarak in Egypt, for example because of their grass-roots networking. Liberal and secular democratic movements lacked anything like this.

In the case of Syria, we have no clear idea yet on the identity of the Syrian rebels.

Hope for the future

But with respect to nonviolent protests in other parts of the Muslim world, this is the kind of paradigm [Wasatia democracy] that many democrats in the Muslim world are attracted to (as opposed to the violent groups for regime change). We cannot make sweeping generalizations about the processes of regime change in Syria, in Egypt, in Tunisia, etc since they are all quite different political scenarios.

And it is the variety of situations throughout the Muslim world that Rahim explores in detail in her book.

Such research does not allow for simplistic assumptions that the problem is “Islam”. In fact such research refutes such popular simplifications. I’d love to get a copy of the book, but it is the better part of $100. A pity. It sounds like the sort of information that should be far more readily accessible to the wider public.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

You could perhaps write to Palgrave Macmillan and ask for a review copy.:-)

Guess they can only say No or ignore my email. 🙂 But I have been encouraged to hear from the author that the work may later this year be available in paperback. I see in the amazon/canadian site that I linked in the post that the Kindle version is even MORE expensive than the hardback copy!!!!

Is there anyone reading this who will be in Sydney this coming Friday evening?

I hope I will be able to acquire this book. Look closely at the quotation at the bottom of this flyer:

Yes I noticed the kindle price too – shocking robbery. I’ve never read anything on kindle. Wouldn’t want to anyway. But I still thought the whole point was that it was cheap. Not so. As for the endorsement by Kessler himself, that’s the most compelling and powerful argument he could have made to demonstrate the necessity that this book should be read by all ‘sides’. Including me.

It seems to me, from the interview, your summary and the blurb on Amazon, that what she claims is beyond refute. It’s historically demonstratable and what I once thought was commonly understood. I do wish those who dismiss Islam with assumptions about a ‘heart’ etc, would honestly read a bit of history. The more I dwell on it the more convinced I am that this book, combined with Espositos must be read for the sake of a future – for god’s sake world, read them and understand….:( (Thinking you could maybe order it for the university library, and borrow it) then…)

As one who has studied and read history all his life I so often find myself dismayed at the utter ignorance of how humans and societies work — as illuminated through some sense of historical awareness — by the likes of some of the most educated people: Not mentioning any names like Jerry Coyne or Richard Dawkins or Sam Harris, of course.

People don’t just wake up one morning as if to day, Hey, it’s after 1979 and the Iranian Revolution, so it’s time that we Muslims starting to take our religion seriously and go out and kill anyone we can define as an enemy. Remember the Barbary Pirates!

Without some sense of history and how people and societies work it is, it appears, so easy to demonize or at least dehumanize people by really believing that such a scenario is essentially realistic.

But we shouldn’t need to study how people work from the text books anyway. There’s something about many of us that does prefer to simplistically categorize “the other” as “other” even in his fundamental human nature.

What good is education that teaches us how to explain the origins of life and the way our brains work if it doesn’t teach us how to follow the simplest of rules to foster a civil society?

Exactly right.

Caliphate—I agree that this idea, as it is emerging now, is a 20th century construct arising out of a need to reform Islam. However, though the people who hold to this idea do not seem to have an agreement as to what it is, IMO, there seems a inclination of mixing sharia with governance (politics)—-which would go against the traditional separation of Law and State in Islam. (there seems to be a perception that sharia is not working and some are proposing that it is not working because there is no “caliphate”—whatever that might mean)

The Quranic meaning of the term—-It is used in the legal concept of “Trust” , that is a settlor (God) gives a duty/responsibility (trust) to a trustee (humanity) for the beneficiary (all of God’s creation). So there is also a “green movement” in Islam based on this idea of Khalifa.

MB [Neil: i.e. Muslim Brotherhood] —Prof Tariq Ramadan proposed that the Egyptian people had to choose the MB because the Saudi/Salafi’s were putting up a lot of financing to influence the Egyptian elections by backing a party of their choosing. Perhaps this dynamic—the idea that Islamists are more neutral—in that secularism is backed by the West and Salifi/Wahabi parties are backed by Saudi’s leave some muslim countries no choice but to back Islamists….?…….I hear that Salafi/Wahabi’s are also active in Tunisia…..but I am not that familiar with the Middle East……..

Sharia—there is a perception in the west that sharia is oppressive. (and it has been used to oppress) but to most muslims Sharia—or Law—means a system of justice based on ethico-moral principles. That is why Muslims want “religion” to be part of governance—-because to muslims religion=ethico-moral principles (not theology—as understood in the west). For example, many Asian democracies are plagued by corruption—but corruption is against the ethico-moral principles of Islam(the Quran advocates for transparency in transactions)—so there is (perhaps a naive) perception that “Islam”(or rather implementing ethico-moral principles) will solve problems of society.

Problems that muslims see today in Asia

—Democracy is corrupted and leads to the “elite” using the state to get richer at the expense of the rest of society

—Capitalism is not working—it makes most of the society poorer while a fraction of the “elite’ get richer

—Justice works for those who have money/power.

(Sharia is based on 3 concepts of “Justice”—-1)Restorative Justice, 2)Retributive Justice, 3)Deterrent Justice—retributive justice is the major system of justice used in the West. The aspect of Sharia that deals with jurisprudence is called Fiqh)

There are some interesting facets to your comment. I have heard the view that the fact that churches are so influential in the United States today owes much to the “business” war against unions and labour in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The only organized groups left standing (after the destruction of secular people’s movements) were the churches.

The same appears to have happened in the Middle East. Iran might be seen as a paradigm. A secular democracy was overthrown by the US and UK and the Shah — who wiped out the secular opposition. That left only the clerics with an organized base and they led the counter-revolution.

What your comment is suggesting is that it is the Muslims/Islamists who are discerning the realities of Western “democracy” (it is really a structure that props up the property owners/elites against the populace) and capitalism (it only works when there are controls and enforced regulations — otherwise it inevitably leads to catastrophe for the majority). That is, in the wake of the secular alternative to capitalist “Liberalism” being wasted (i.e. the demise of the old “Left” as it was expressed through major institutions and States), the Muslim religion (as much and more on a global scale) has filled in the gap left by the demise of the “Left”.

It will be interesting if the end result will be another compromise — as it was, by way of one example, with the Left going back to the days of the New Deal in the US; or with the rise of moderate welfare and socialist semi-controlled economies in Europe.

Not suggesting any simplistic parallel. There are always new factors. Change in the world is accelerating, there is climate change, a superpower sensing it is may be on the verge of moving into a twilight zone . . . . If so, then Rahin’s analysis and prognosis would prove correct: Wasatia/Wasatiyyah Democracy — That should appeal to Americans, too. I gather a good many of them, no more than Muslims, can abide the idea of a state that does not tolerate a public face to religion.

But the along come China and India . . . . .

Iran—It is an interesting case because the traditional separation of law and state was not implemented. Instead a new idea proposed by Khomeni—that of Vilayat-e-Faqhi—that Judges(Faqhi) should rule the country—ended up merging law and state together.

(Though the cause is different, S. Arabia also has a similar problem—IMO, the monarchy is too weak (or perhaps uninterested) to create an appropriate balance of power.)

Capitalism–if this is defined as an economic concept of producing goods for profit, this works fine in the Islamic/Quranic framework—except that Islam/Quran adds to this economic concept by balancing it with a system/concept of distribution/circulation of wealth. The major difference is that the (Islamic) economic system is not based on debt/interest. (debtor and creditor work somewhat as a partnership)

New Deal—Ibn Khaldun (14th Century) proposed that large governments and large armies were inefficient and government should instead spend money to improve the conditions of the subjects. He proposed low taxes so that people invest their wealth in the growth of the economy. Rather than a consumer based economy—a system in which consumption dictates growth—-Ibn Khaldun envisioned a “value” economy—one in which increasing the quality of the products created higher value and this in turn created greater circulation of wealth………….These ideas may be too old to use today—nevertheless, perhaps they can still be used as a jumping-off point when thinking of a new/different system…………….

Social justice—This is is an issue that both government and citizens have to solve together—in that, it is not the sole responsibility of the government. Citizens are closer to their communities and can work out unique solutions that adapt to the circumstances and problems of the community—a “one-size fits all” type of government solution can be ineffective.

China/India—are both grappling with problems of waste and wide income disparity. Much of Asia is in a growth stage so some of the problems may not be as visible now—but if we are not careful, the problems the west is facing today will eventually plague Asia as well………..

I agree that changes in geo-politics, demographics and climate might create an unpredictable future—but perhaps also an interesting one…..

It seems that this sort of phenomenon isn’t unique to Islam: Epiphenom: Do the rich use religion to keep the poor in their place?

Historically we find some of the most blood-stained rulers in the Middle Ages (let’s say around the ninth century) bestowing prestige and gifts upon religious orders as if to assuage their guilt; and then the thesis that the rise of capitalism was directly related to Protestantism.

“Not a new idea, of course”

Goes back to Critias, if not earlier.

http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/4182561?uid=3737536&uid=2129&uid=2&uid=70&uid=4&sid=21102183120281

And used by Marx.

The Caliphate(s)

This is from “Setting the record straight on the caliphate: early Islamic history carries the seeds for contemporary reforms” by Asma Afsaruddin, associate professor of Islamic studies at the University of Notre Dame, published in the National Catholic Reporter. 42.24 (Apr. 14, 2006): p18

The above is an accurate explanation…..I would like to add a few words…………

the seeds for contemporary reforms—“Rightly Guided Caliphs” is a term used in contrast to later “Caliphs” —that is, the later Caliphs are considered leaders but the Rightfully Guided Caliphs are considered Trustees (In the Quranic sense of the word). The 4 Caliphs as well as the Prophet (pbuh) were “elected”/chosen—though it was initially by a committee, approval/allegiance was also sought from the community/citizens. Government was understood as a contract between the leader(trustee) and the citizens (beneficiary). In this system both the governor and the governed have responsibilities. (later Caliphs did not use this system—but it is this idea—government FOR the people—that is admired today)

(Though the seeds were planted earlier, development of full economic systems, bureaucracy, schools of sharia, universities, public libraries…etc are 8th century onwards—and thus after the period of the Rightly Guided Caliphs—which ended in approx 661 CE.)

(The oldest university still in operation today is Al Qarawiyin est. in 859 CE )

Muslims see Islam itself as a reform movement—it brought peace to a war-torn society and established principles of brotherhood, equality, law and justice, rights and responsibilities, and the pursuit of knowledge. However, human endeavors, no matter how well intended, are imperfect….and 1,400 years of Muslim history (including the period of the 4 Caliphs) can also be understood as a slippery struggle to live upto the ideals and ethico-moral principles of the Quran and Prophet (pbuh)….a struggle that is still unfinished………..

How does this study inform us on whether or not Islam is compatible with democracy?

http://www.wzb.eu/sites/default/files/u6/koopmans_englisch_ed.pdf

The article tells us a few things about Muslims in Holland and Europe and reinforces Ruud Koopman’s reputation in that scene. (Europe is notorious for its discrimination and rejection of Muslims generally by contrast with North America.) Keep reading, keep learning. You will eventually learn something about the differences in the ways Muslims are accepted and treated in different parts of the Western world, and their differences within Europe, North Africa, Middle East and Southern and South-East Asia and North America and Australia. When you put it all together you will begin to understand why Dutch professors identify the things they do in a certain part of the world and you will learn a lot about statistics and Muslims more generally and how to explain their many differences across the different geo-political-social-economic regions of the world.