Some readers may have come across a very long list of ancient writers who “could or should” have made some mention of Jesus. That list surfaced in another forum discussion today and I found myself faithlessly writing a response to it there instead of spending my time on Vridar. To make amends, hoping Vridar will not feel offended or as if being treated second-class, I copy below what I wrote in the Afa forum.

Such a list serves as a reminder of the riches in sources that are available for the early Roman empire period compared with many other periods of ancient times.

What is fundamental to historical research is the necessity to independently corroborate sources and their claims. It’s not the only requirement but I have a hard time thinking of many ancient figures that are securely known to have existed without meeting that benchmark in the records.

I have listed below what I think are the fundamentals that historical researchers look for when examining the documentary sources. Independent corroboration is left to last

- Documents need to be assessed for authenticity;

— that includes being able to trace their provenance, assess when they were possibly written, where, etc.

- their authors ideally need to be identified in order for the investigator to have some idea of how likely they were to have access to certain information, what biases and agendas they may have had, etc;

— We have such information for a good number of ancient authors

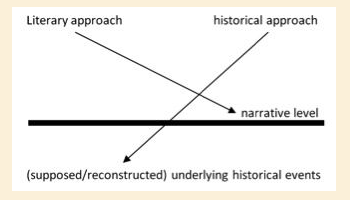

- the literary culture that forms the matrix of the document needs to be understood in order to guide analysis and interpretation;

— we need to understand the conventions of ancient historians and the proclivities of individuals: e.g. their tendency to invent historical accounts drawing upon classical epics and plays when their sources failed them

- we need to be able to identify and evaluate the probable sources of ancient documents;

— were they relying upon historians before them and if so, which ones, when did they live, what reasons do we have for thinking their work to be reliable, etc

— part of this requirement is the acknowledgment that contemporary sources must form the basis of historical reconstructions. Sometimes later sources can be more reliable or act as checks but they can only rarely be a trusted starting point for historical inquiry

- and claims made in the documents need to be independently corroborated

— e.g by archaeology, by ancient monuments and inscriptions, by contemporary documents by unrelated authors, etc.

These are the fundamentals. Obviously such processes leave the historian with less data than historians of more recent times have at their fingertips. That doesn’t mean that historians of ancient world lower their standards, however. It means instead that they ask broader questions or the sorts of questions that they know their sources will help them answer.

It also means there is often less certainty in some of their conclusions.

When it comes to the study of Jesus, historians are on the back foot with almost all of the above: Continue reading “Fundamentals of historical research and the difficulties faced by historical Jesus studies”