Only the most manic conspiracy theorist would question the fact that the Battle of Hastings took place in 1066, or that a man landed on the moon in 1969, or that the Holocaust took place. . . . . It is a fact that Caesar crossed the Rubicon and invaded Italy in 49 BC; going back to the sources in an attempt to prove or disprove this would be as much a waste of time as reinventing the wheel.

(Morley, 59)

When the ancient historian Neville Morley wrote those words he unfortunately made it sound tedious to go back and pore through papers and documents and books to find out “how we know” they happened. But it is not a difficult task at all, especially now that since Morley wrote we have a vastly improved internet fact-finder.

Two of Morley’s examples are not at all problematic. We know we have abundant contemporary sources to verify the moon landing and Holocaust. But what about the facts in medieval and ancient history?

Here is how we know . . . .

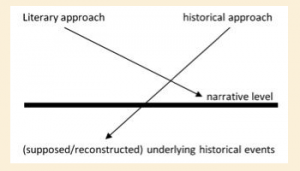

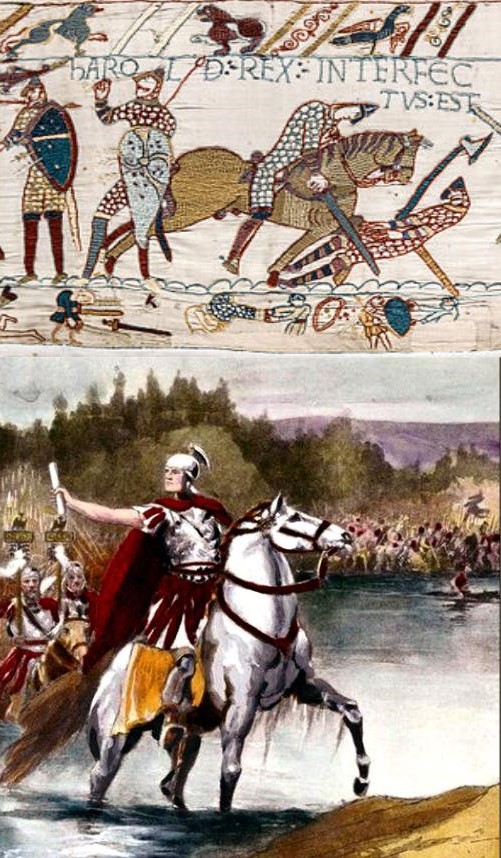

the fact that the Battle of Hastings took place in 1066

Search for “Battle of Hastings” and “Primary sources”. In quick time you will find the data that has long assured us that this battle happened and it was in 1066. Example: Spartacus Educational — Battle of Hastings. One sees at the top of that page a link to Primary Sources. If you haven’t already, click on it. In front of will be a list of the following and even more conveniently translations of the texts:

(1) Message sent by William of Normandy just before the Battle of Hastings took place (quoted by William of Poitiers in Deeds of the Dukes of the Normans (c. 1070)

(2) Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, D Version, entry for 1066.

(3) William of Malmesbury, The Deeds of the Kings of the English (c. 1140)

(4) William of Poitiers, The Deeds of William, Duke of the Normans (c. 1071)

A message by William of Normandy himself? Quoted by a contemporary? That looks strong evidence, but is there corroboration from another source?

A Chronicle of the time. Now that’s strong. “D Version” looks a bit baffling but a bit more searching will bring up an explanation that the particular manuscript in mind is that of Worchester.

Number (4) is a bit late so we would have to read it to check on the sources the author used. That’s not very difficult nowadays, either. Just one more click away.

That’s how we know the Battle of Hastings took place in 1066. Sources from contemporaries.

Here is how we know . . . .

that Caesar crossed the Rubicon and invaded Italy in 49 BC

Again, a little hunting and pecking on the web, or looking up a scholarly publication about the event, or asking a classicist, will quickly inform us that we have Julius Caesar’s own “memoirs” or “commentary” on the Civil War in which he tells us that (and when) he crossed over into Italy with his army, thus precipitating the Civil War.

We have Julius Caesar’s own written account of the circumstances that led him to cross into Italy in the Commentaries on the Civil War (1:8) (Don’t be put off by Caesar’s odd-sounding practice of referring to himself in the third person.) Caesar did not explicitly mention the provincial border he crossed (he only said he marched into Italy as far as Rimi or Ariminum twelve miles south of the river) but we have the explicit reference to the Rubicon in a written speech by Cicero, Caesar’s contemporary. And then we have several later historians who had access to archives writing about Caesar. But on the combined strength of Caesar’s own testimony and the testimony of his contemporary we can safely say that Caesar did indeed cross the Rubicon thus precipitating the civil war.

What we don’t know as a fact . . . .

Morley explains: Continue reading “How Historians Know Their Bedrock Facts”