Would the Gospels be any more credible if their authors clearly left their names in them, along with a little biographical information clearly linking them to known historical persons, and if they at every point in their narrative informed readers of their sources for each set of sayings by Jesus and for each incident? Some sources they would explain were oral witnesses, some were official documents, maybe even some inscriptions that could be verified by any person in the region in their day.

Supposed a critic still dismissed them as fabricated tales. Would we be outraged that such a critic was completely biased against the Gospels and that she would never be so sceptical of secular writings with such an abundance of confirming testimony?

The answer ought to be that “it all depends”. It all depends on a critical analysis of all of that information. That would not be being biased against the Gospels. It would be treating the Gospels in exactly the same way scholars worth their salt treat their secular sources.

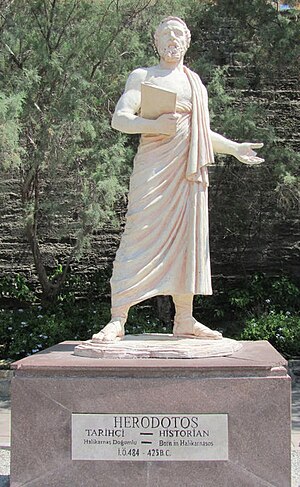

Take studies of Histories by Herodotus for instance. Herodotus has long been considered an essential source for our knowledge of the ancient world. By his own testimony he traveled widely, examining cultures first hand and gathering information from a wide range of sources, oral and written. Sure some of his tales are clearly fabulous, but why should we doubt that even those have some historical core in many cases?

1989 saw the English translation of Detlev Fehling‘s Herodotus and His ‘Sources’: Citation, Invention and Narrative Art, originally published in German in 1971. I will post from time to time on aspects of this book but for now let me outline his main arguments as summarized by Katherine Stott in Why Did They Write This Way? Reflections on References to Written Documents in the Hebrew Bible and Ancient Literature (2008): Continue reading “What if the Gospels did cite their sources and identify their authors?”