Philip R. Davies, In Search of Ancient Israel (1992) pp. 35-36

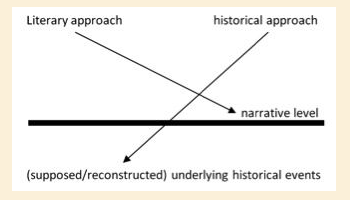

historical research by biblical scholars has taken a . . . circular route, whose stages can be represented more or less as follows:

Davies then lists the four assumptions that these scholars have brought to their study:

1. The biblical writers, when writing about the past, were obviously informed about it and often concerned to report it accurately to their readers. A concern with the truth of the past can be assumed. Therefore, where the literary history is plausible, or where it encounters no insuperable objections, it should be accorded the status of historical fact. The argument is occasionally expressed that the readers of these stories would be sufficiently knowledgeable (by tradition?) of their past to discourage wholesale invention.

2. Much of the literature is itself assigned to quite specific settings within that story (e.g. [the time of Tiberius, Pilate, Herod, Gallio, Gamaliel, Agrippa]). If the biblical literature is generally correct in its historical portrait, then these datings may be relied upon.

3. . . . Thus, where a plausible context in the literary history can be found for a biblical writing, that setting may be posited, and as a result there will be mutual confirmation, by the literature of the setting, and by the setting of the literature. . . .

4. Where the writer (‘redactor’) of the biblical literature is recognized as having been removed in time from the events he describes or persons whose words he reports . . . he must be presumed to rely on sources or traditions close to the events. Hence even when the literary source is late, its contents will nearly always have their point of origin in the time of which they speak. The likelihood of a writer inventing something should generally be discounted in favour of a tradition, since traditions allow us a vague connection with ‘history’ . . .

But Davies sees those four assumptions as flawed:

Each of these assertions can be encountered, in one form or another in the secondary literature. But it is the underlying logic which requires attention rather than these (dubious) assertions themselves. That logic is circular. The assumption that the literary construct is an historical one is made to confirm itself.

Here are Davies’ rejoinders to each of the assumptions above, taken from my vridar.info page:

#1 This claim simply asserts, without proof, that the Bible is true. It is just as easy to claim that bible authors made everything up.

#2 This again just assumes without proof that the Bible is true. It is just as easy to assume that the authors, like fiction writers of all ages, chose real settings for their stories.

#3 Good story tellers always try to add color to their fictions by touching them up with realistic details. No-one says that James Bond stories are true just because they are set in times of real Russian leaders, true places, etc.

#4 This is simply asserting, without evidence, that the stories must be true “because” we know they must have been true! One can just as easily assume that the stories were invented.

The solution for Davies?