The universality of religion across human society points to a deep evolutionary past. However, specific traits of nascent religiosity, and the sequence in which they emerged, have remained unknown. Here we reconstruct the evolution of religious beliefs and behaviors in early modern humans . . . . (Peoples, Duda, Marlowe, 261)

Of interest to most of us is the question of God. Belief in a high god, we will see, does not “come naturally”. We can conclude (and as I will further show in future posts) that belief in God is associated with the development of complex societies. (More specifically this post addresses “traits of religion” since “religion” as an abstract concept was alien to many ancient cultures, with what we would consider to be religious beliefs and practices being, to the ancients, a natural part of everyday life.)

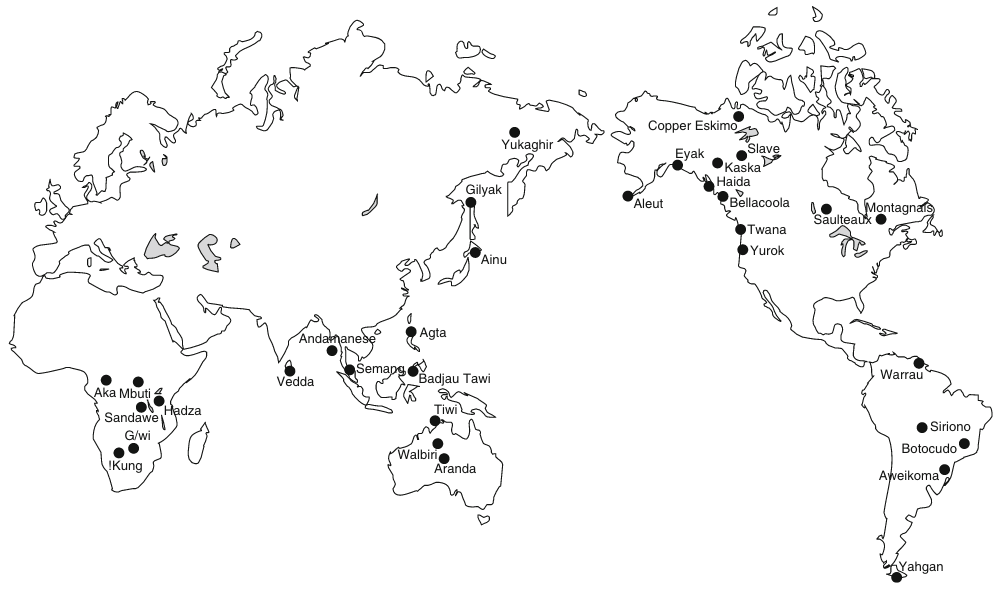

We began our evolutionary journey with a study of hunter gatherers since it is reasonable to infer they represent or earliest way of living.

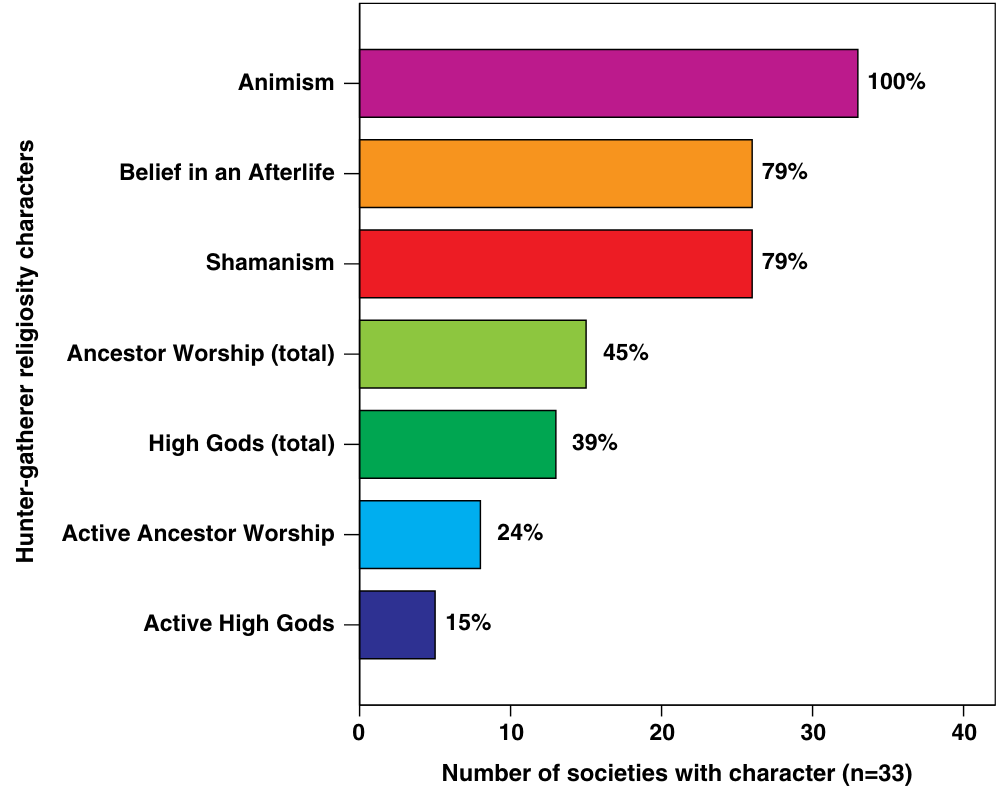

There are many traits of religion and seven were looked for and studied:

1. Animism

We define animism as the belief that all “natural” things, such as plants, animals, and even such phenomena as thunder, have intentionality (or a vital force) and can have influence on human lives. (266 — some will baulk at classifying animism as a religion but it is undeniably a “trait of religion”, “the oldest trait of religion” and “fundamental to religion”.)

2. Belief in an afterlife

Belief in an afterlife is defined as belief in survival of the individual personality beyond death …. (266)

3. Shamanism

We define shamanism as the presence in a society of a “shaman” (male or female), a socially recognized part-time ritual intercessor, healer, and problem solver …. Shamans often use their power over spirit helpers during performances involving altered states of consciousness … to benefit individuals and the group as a whole …. We view shamans as a general category of individuals often found in hunter-gatherer societies who mediate between the earthly and spirit worlds to promote cohesion and physical and mental well-being in the society …. (266)

4. Ancestor worship

Ancestor worship is defined as belief that the spirits of dead kin remain active in another realm where they may influence the living, and can be influenced by the living …. (p. 266)

There are various types of ancestor worship:

- spirits can be present but not necessarily active in human affairs;

- they may or may not be influenced by humans through prayer and offerings.

5. High gods

… single, all-powerful creator deities who may be active in human affairs and supportive of human morality. (p. 266)

As with ancestor worship there are variants:

- some high gods can be present but not interested in humans;

- or they can be active in human affairs but not interested in moral conduct;

- or they can be active in judging behaviour and punishing immorality.

6. Worship of active ancestors

7. Worship of active high gods

And here is their result. The graph illustrates how often the respective types of religious belief were found across the 33 societies:

Conclusions

Animism

Our results reflect [the] belief that animism was the earliest and most basic trait of religion because it enables humans to think in terms of supernatural beings or spirits. Animism is not a religion or philosophy, but a feature of human mentality, a byproduct of cognitive processes that enable social intelligence, among other capabilities. It is a widespread way of thinking among hunter-gatherers …. This innate cognitive trait allows us to attribute a vital force to animate and inanimate elements in the environment …. Once that vital force is assumed, attribution of other human characteristics will follow…. Animistic thinking would have been present in early hominins, certainly earlier than language (Coward 2015; Dunbar 2003).

It can be inferred from the analyses, or indeed from the universality of animism, that the presence of animistic belief predates the emergence of belief in an afterlife.

(Peoples, Duda, Marlowe, 274 — my bolding in all quotations)

Our basic psychology that makes it so easy for us to believe in spirit forces has been discussed in earlier posts:

In brief,

The fundamental building blocks of religious thinking and behaviour are found in all human societies around the world – from small-scale indigenous communities to industrial conurbations and inner cities. For example, people everywhere imagine that bodies and minds can be separated, that features of the natural world have hidden essences and purposes and that we ought to please and placate the spirits of the dead. People everywhere are inclined to spread stories about miraculous events and special beings that contradict our intuitive expectations about the way the world works, giving rise to a plethora of beliefs in supernatural beings and forces of various kinds. People everywhere – even babies who have not yet learned to speak – experience feelings of awe and reverence when they encounter those who can channel otherworldly powers. (Whitehouse, 42f)

Animism would appear to be the fundamental human universal.

Our results indicate that the oldest trait of religion, shared by the most recent common ancestor of present-day hunter-gatherers, was animism. This supports longstanding beliefs about the antiquity and fundamental role of this component of human mentality, which enables people to attribute intent and lifelike qualities to inanimate objects and would have prompted belief in beings or forces in an unseen realm of spirits. (Peoples, Duda, Marlowe, 277)

The following traits of religion are contingent. Why some hunter gatherers embraced the following is a follow-up question. But animism is fundamental: animism is the precondition for all the other traits.

Afterlife

Many but not all groups acquire a belief in an afterlife or embrace shamanism.

Once animistic thought is prevalent in a society, interest in the whereabouts of spirits of the dead could reasonably lead to the concept of an unseen realm where the individual personality of the deceased lives on. The afterlife might be a rewarding continuation of life on earth, or a realm of eternal punishment for those who break social norms. Belief in an afterlife may have generated a sense of “being watched” by the spirits of the dead, prompting archaic forms of social norms … actualized in the role of the shaman. (Peoples, Duda, Marlowe, 274)

On the “naturalness” of believing in an afterlife:

While most wild religious beliefs were not selected for in the human evolutionary journey, they came about as a side effect of other, more adaptive psychological characteristics: for example, our intuitive psychology (including the way we anticipate how others will behave), our intuitive biology (such as the way we create taxonomies of the natural world), our tool-making brains (which make us think everything has a purpose) and our tendency to overdetect agency in the environment (particularly our early warning systems for detecting predators). These intuitions helped our ancestors to survive and pass on their genes, but they also make us naturally susceptible to believing in an afterlife; they make us treat certain objects or places as sacred; they lead us to think that the natural world was intelligently designed; and they convince us that invisible and dangerous spirits lurk in caves and forests.

. . . .

This ability to reason about the mental states of others [“theory of mind”] has profound consequences for our ideas about spirits and the afterlife. A good example of this is … an attempt to explain beliefs in the afterlife as a side effect of the way we naturally reason about minds. … The idea of a ghost or spirit of the dead results from the impossibility of imagining the elimination of certain mental states….

In other words, we imagine the spirits of the dead to remember things that happened during their lives, to have feelings, and to form judgements even if we know that their bodies (including their eyes and their ears) no longer function and may be incinerated or rotting in the ground. This theory is consistent with the very early development of such assumptions in children.

(Whitehouse, 53f)

Belief in afterlife is a precondition for shamanism and ancestor worship.

Shamanism

Shamanism significantly correlates with belief in an afterlife, which emerged first….

Although shamanism has been described as the universal religion of Paleolithic hunter-gatherers … it is not a religion per se, but a complex of beliefs and behaviors that focus on communication with the ancestral spirits, as well as the general world of spirits in the realm of the afterlife. Shamans are healers, ritual leaders, and influential members of society …. Communication with omniscient and perhaps judgmental spirits of known deceased, including ancestors, would have been a useful tool in the work of the shaman….

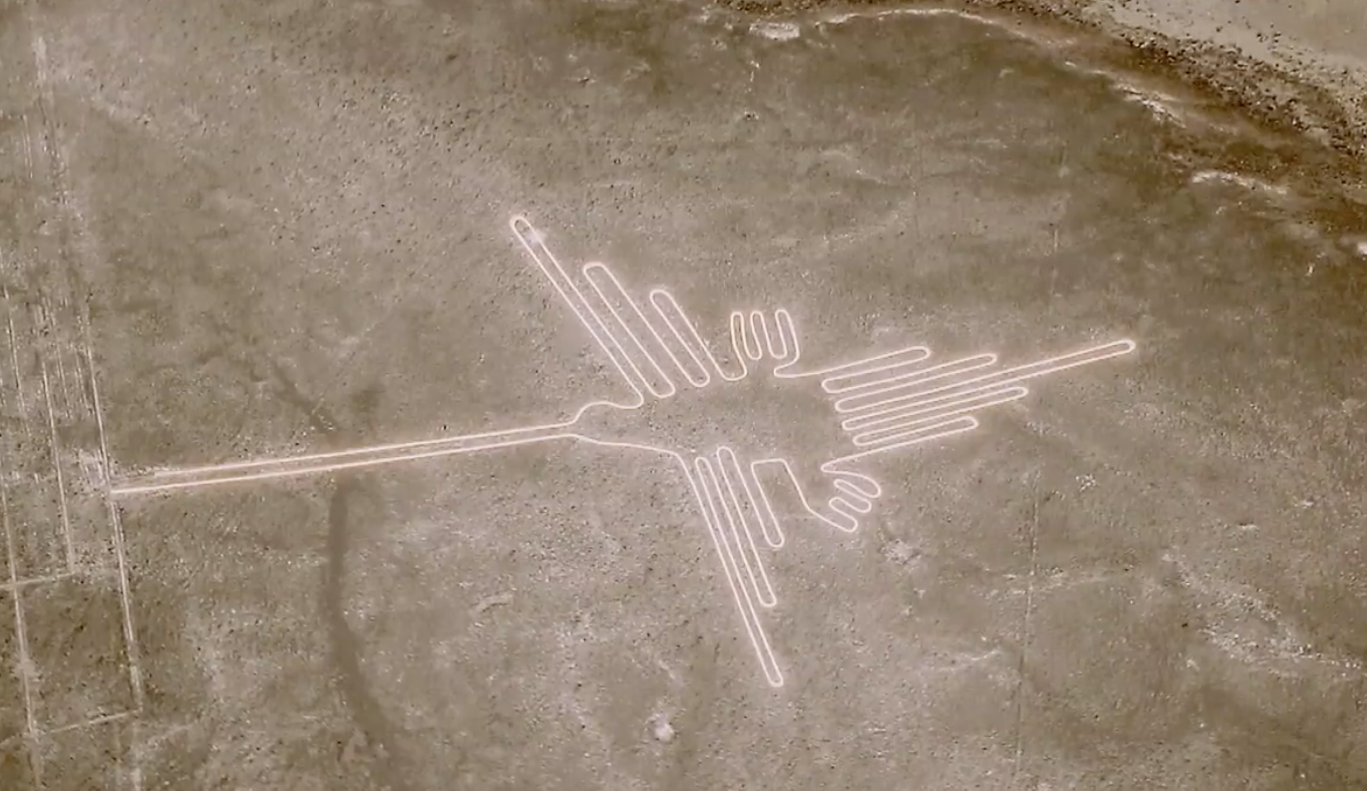

As humans migrated out of Africa more than 60 kya … the shaman’s curing skills and group rituals would have enhanced survival through physical and emotional healing, enforcement of group norms, and resource management. (Peoples, Duda, Marlowe, 274f)

Ancestor worship

Ancestor worship is not commonly found among hunter-gatherer societies. In future posts I will address research that points to a very strong association between ancestor worship and early agricultural societies.

Worship of dead kin is neither widespread among hunter-gatherers nor the oldest trait of religion. Fewer than half of the societies in our sample believe that dead kin can influence the living…. Greater likelihood of the presence of active ancestor worship [i.e. worship of ancestors actively interested in human affairs] has been linked to societies with unilineal descent where important decisions are made by the kin group…. Ancestor worship is an important source of social control that strengthens cohesion among kin and maintains lineal control of power and property … particularly in the more complex hunter-gatherer societies. In contrast, immediate-return hunter-gatherer societies … seldom recognize dead ancestors who may intervene in their lives. (Peoples, Duda, Marlowe, 275)

The latecomer in the evolution of human societies is “God” . . . .

High gods

Belief in a high god is an outlier in the study. Where it is found the researchers suspected it the belief was acquired from borrowing instead of being organically evolved in the group. (See the original article for a detailed explanation of the ways and extent to which the above religious traits are associated with one another, and the evidence that the belief in high gods is not associated with any other early attribute.)

Belief in high gods appears to be a rather “stand-alone” phenomenon in the evolution of hunter-gatherer religion. Prior studies have shown that among the four modes of subsistence (hunter-gatherers, pastoralists, horticulturalists, and agriculturalists) hunter-gatherers are least likely to adopt morally punishing active high gods, if any high gods at all (Botero et al. 2014; Norenzayan 2013; Peoples and Marlowe 2012; Swanson 1960)…. Early egalitarian hunter-gatherers would rarely have acknowledged an active high god (Norenzayan 2013; Peoples and Marlowe 2012) and would be the least likely to accept or benefit from the supernatural meddling and social constraints of deities who would be seen as “high rulers” (Peoples and Marlowe 2012). The leaders of complex hunter-gatherer societies whose subsistence relies on collective effort should be more likely to benefit from the coercive power of a punishing high god. Our analysis does not support the prevalence of either type of high god among ancestral hunter-gatherers, and the evolution of high gods does not correlate with any of the other traits of hunter-gatherer religion, including ancestor worship. (Peoples, Duda, Marlowe, 276)

God, we will see in more detail in coming posts, appears in certain kinds of socially complex societies:

If a society acquires belief in an omniscient and potentially morally punishing creator deity, it does so regardless of other aspects of its religion but more as a reflection of its social and political structure. (Peoples, Duda, Marlowe, 278)

Guthrie, Stewart. Faces in the Clouds: A New Theory of Religion. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Peoples, Hervey C., Pavel Duda, and Frank W. Marlowe. “Hunter-Gatherers and the Origins of Religion.” Human Nature : An Interdisciplinary Biosocial Perspective 27, no. 3 (September 2016): 261–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-016-9260-0.

Whitehouse, Harvey. Inheritance (pp. 42-43). Cornerstone. Kindle Edition.