After having posted sympathetically about the possibility of our lacking free will (so much so that I am not even sure I know what “thinking” entails at the most fundamental level) — I’m pleased to imagine that I am freely choosing to post a link to an argument for us having free will:

by Kevin Mitchell, a scholar of genetics and neuroscience at Trinity College Dublin.

The processes of cognition are thus mediated by the activities of neurons in the brain, but are not reducible to those activities or driven by them in a mechanical way. What matters in settling how things go is what the patterns mean – the low-level details are often arbitrary and incidental. Organisms with these capacities are thereby doing things for reasons – reasons of the whole organism, not their parts.

and

A common claim of free will skeptics is that we, ourselves, had no hand in determining what that configuration is. It is simply a product of our evolved human nature, our individual genetic make-up and neurodevelopmental history, and the accumulated effects of all our experiences. Note, however, that this views our experiences as events thathave happened to us. It thus assumes the point it is trying to make – that we have no agency because we never have had any.

If, instead, we take a more active view of the way we interact with the world, we can see that many of our experiences were either directly chosen by us or indirectly result from the actions we ourselves have taken. Not only do we make choices about what to do at any moment, we manage our behaviour in sustained ways through time. We adopt long-term plans and commitments – goals that require sustained effort to attain and that thereby constrain behavior in the moment. We develop habits and heuristics based on past experience – efficiently offloading to subconscious processes decisions we’ve made dozens or hundreds of times before. And we devise policies and meta-policies – overarching principles that can guide behaviour in new situations. We thus absolutely do play an active role in the accumulation of the attitudes, dispositions, habits, projects, and policies that collectively comprise our character.

More at his blog — http://www.wiringthebrain.com/

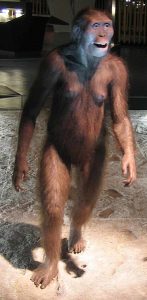

He also has a book titled Free Agents, subtitled How Evolution Gave Us Free Will.

The experience of one friend of mine many years ago still haunts me. He had enormous emotional, mental and behavioural problems, having come from a brutal family upbringing. There was one period when he seemed to have completely changed, to have become “whole” even, and positive. It turned out that he had had a good sleep and a healthy meal for once. I was religious at the time and could not help wondering how God would judge someone whose behaviour depended so critically on a healthy salad sandwich and 8 hours sleep.