Continued from Review 3 . . .

Continued from Review 3 . . .

And when it is pointed out that, after all, we are talking about texts written in Koine Greek (and so the language ability is pretty important), and that . . . requires a lot of study, all this if one wishes to make some kind of soundly-based judgement . . . (Hurtado 2012)

Serious historians of the early Christian movement—all of them—have spent many years preparing to be experts in their field. Just to read the ancient sources requires expertise in a range of ancient languages: Greek, Hebrew, Latin . . . not to mention the modern languages of scholarship (for example, German and French). And that is just for starters. Expertise requires years of patiently examining ancient texts . . . . (Ehrman 2013, 4f)

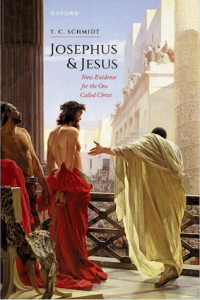

When a scholarly book is made open access in order to reach an audience as wide as possible one would expect many lay readers to feel out of their depth when reading claims about the meaning of the Greek words in Josephus’s passage about Jesus (the Testimonium Flavianum / TF).

As I mentioned earlier, I have since taken up formal studies in ancient Greek and have acquired enough awareness of the technicalities of ancient Greek and a knowledge of the reference tools used by scholars to see when baseless arguments are being fed to lay readers. In this post I take interested readers through a citation trail that Thomas Schmidt initiated in order to confirm his claim that Josephus was deliberately encouraging willing readers to interpret a passage about Jesus in a negative light. We will see by the end that the citation trail not only fails to support Schmidt’s case but even arguably points to its opposite – that the original Greek is meant to be understood in a positive sense. Most certainly we will see that there is no suggestion of the ambiguity for which Schmidt argues.

Schmidt’s argument re ἐπηγάγετο (epēgageto)

. . . and he [Jesus] brought over many of the Jews and many also of the Greeks . . . (TF)

Other translations for “brought over” (i.e. ἐπηγάγετο) read:

. . . “led astray / led away” (other possibilities listed by Schmidt)

. . . “won over” (Feldman)

. . . “drew over” (Whiston)

. . . “gained a following from” (Meier)

. . . “led astray” (Morton Smith)

. . . “attached to himself” (Zeitlin)

. . . “attracted” (Mason)

. . . “seduced” (Eisler)

In Schmidt’s view, Josephus wrote with careful ambiguity about Jesus attracting followers. Josephus, he explains, wrote the equivalent Greek words of Jesus “bringing over” many persons because the Greek for “bringing over” or “brought over” could be read either positively or negatively or neutrally:

. . . the evidence demonstrates that such phrasing could well have been interpreted neutrally, ambiguously, or negatively by one who was so inclined. (Schmidt 2025, 83)

In the end, Schmidt sums up by saying that Josephus meant to describe Jesus “somewhat neutrally”. I’m not sure what “somewhat neutrally” means. What would it mean to describe a referee of a game as “somewhat neutral” or a judge hearing a trial as “somewhat neutral”? Is it like being “somewhat pregnant”?

But here is his point that I want to discuss in this post:

Josephus then uses the ambiguous term ‘brought over’ (ἐπηγάγετο) to describe Jesus leading many Jews and Greeks. This word can be interpreted as connoting deception, exactly like what Jewish leaders accused Jesus of doing according to the Gospel accounts (Matthew 27:63; Luke 23:2; John 7:12, 47, 52). (Schmidt 2025, 208)

And that is important for Schmidt: for Schmidt, the words we read in Josephus have to allow for – and even subtly infer – a negative view of Christianity. So Schmidt continues,

Moreover, the Gospels describe how Jesus’ many followers caused great alarm among Jewish leaders (John 4:1-2) who worried that the ‘whole world’ was going to follow him (John 12:19) and that Jesus would cause a rebellion (Luke 23:1-5, 14). All this is once again corroborated by Josephus’ portrayal of Jesus leading ‘many from among the Jews and many from among the Greeks’ and then being crucified by the Roman governor at the behest of Jewish leaders. The reader of the TF is thus left with a fair impression that Jesus may have been accused of fomenting rebellion . . . (Schmidt 2025, 208 – my bolding)

[Josephus] further preserves the term ἐπηγάγετο [“brought over”] which can be understood as ‘he led astray’.19 (Schmidt 2025, 218)

Notice once again that Schmidt uses passages from the Gospels as evidence of historical words spoken and the historical feelings of Jewish leaders. He interprets Josephus through those gospel narratives. (There are many reasons this is a problematic way to understand Josephus, too many to repeat here though I have discussed them many times elsewhere as part of what consists of basic sound historical method.)

Schmidt cites other scholarly works and references and even other passages in Josephus to establish his claim that by “brought over” Josephus was subtly implying – and that the reader was meant to notice – that Jesus was “leading astray” many followers. Before I demonstrate that all his references and supports fail to make this case, I must explain for most of us the most obvious meaning of the Greek word translated “brought over” (or even possibly “misled” or “led astray”).

The meaning of ἐπηγάγετο

If I say “Mary led the lamb to her school” no-one is going to suspect, because I had spoken of a butcher leading a heifer to his abattoir on another occasion, that Mary was planning to eat her lamb for lunch.

The word translated “brought over” or “led astray” etc is epēgageto (ἐπηγάγετο). It is simply the word for “bring” or “lead” (agō = ἄγω) combined with the preposition for “over” (epi = ἐπί). The base word is thus ἐπάγω, meaning “I bring or lead over”. ἐπηγάγετο is one of the many forms of ἐπάγω. The forms vary according to tense, case, person, number, voice.

One would not expect the word to have any more negative innuendo than the English words for “bring” or “lead”. One can bring or lead others for good or bad reasons. Example:

The guide led/brought the hikers back to his camp.

or

The bandit led/brought his gang to his hideout.

The word for “led” or “lead” or “brought” does not in itself have a good or bad meaning. Only the context can decide if it is being used to describe a positive or negative action. It is no different with the Greek. If I tell a story of events that “led” many people over many years into tragic circumstances, it does not mean that my use of the word “led” in itself conveys something bad. The next time I use the word “led” could be to convey a completely different type of event, let’s say a very happy one, or simply a neutral one. What counts is the context. If I say “Mary led the lamb to her school” no-one is going to suspect, from those words alone or because I had spoken of a butcher leading a heifer to his abattoir on another occasion that Mary was planning to eat her lamb for lunch.

It is the immediate context that determines the meaning of many of the words we use, not some other context where we used the same words once before.

Josephus: “somewhat” neutral? ambiguous? negative?

Let’s now examine Schmidt’s supporting evidence for his claim that the Greek word for “brought over” can and does, at least for Josephus, suggest the meaning of “led astray” or “misled”.

. . . the potentially negative ‘he brought over’ or ‘he misled’ (ἐπηγάγετο) (Schmidt 2025, 47)

. . . a far more ambiguous or possibly negative valence than the one implied by how scholars have traditionally translated it . . . revolves around the meaning of the Greek word ἐπάγομαι, which can mean ‘to lead’ someone in a neutral sense,146 or, according to LSJ and the Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek, it may have the negative connotations of ‘induce’ or otherwise mislead.147

146 For this neutral meaning, see Antiquities 1.263, 2.173.

147 LSJ, ἐπάγω, II 6; Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek, ἐπάγω. So, Thucydides relates how the Argives ‘induced the Spartans to agree’ (ἐπηγάγοντο τοὺς Λακεδαιμονίους ξυγχωρῆσαι) to a treaty even though it seemed quite foolish; Thucydides, Peloponnesian War 5.41.2 line 8 (= TLG 0003.001). On this interpretation of ἐπάγομαι, see also Bermejo-Rubio, ‘Hypothetical Vorlage’, 354–5; Cernuda, ‘El testimonio flaviano’, 373–4. (Schmidt 2025, 81)

It won’t hurt to keep in mind Schmidt’s acknowledgement that the word can indeed be used neutrally. Here are the examples from Josephus that he cites:

He makes a friendship with him beforehand, bringing Philochus, one of the generals, along. (Antiquities 1.263 – translations are from Perseus Tufts unless otherwise noted)

[ = φιλίαν ἄνωθεν ποιεῖται πρὸς αὐτὸν ἕνα τῶν στρατηγῶν Φίλοχον ἐπαγόμενος. – that is a participial form. Schmidt says this is a “neutral” use of the word but others might even see it as a “positive” use, given its context of friendship.]

Sent alone to Mesopotamia, you gained a good marriage, and returned bringing a multitude of children and wealth. (Antiquities 2.173)

[ = τὴν Μεσοποταμίαν μόνος σταλεὶς γάμων τε ἀγαθῶν ἔτυχες καὶ παίδων ἐπαγόμενος πλῆθος καὶ χρημάτων ἐνόστησας. – again, I am not sure why Schmidt chose to describe this form of the word as connoting a neutral meaning; it looks very positive to me.]

So after acknowledging that the word does not have any intrinsic negative flavour Schmidt must demonstrate that for Josephus and the TF this common rule did not apply.

To establish his point, Schmidt introduces major reference works buttressed by scholarly articles.

LSJ is the abbreviation for the Liddell-Scott-Jones Greek-English Lexicon. You can see for yourself all of the ways the root word for has been used in ancient Greek literature at LSJ: ἐπάγω. Schmidt directs readers to II 6. The II section, we discover from the abbreviation beside it, Med., lists the way the middle voice form of the word has been used and translated. The middle voice is the form or a verb that indicates it is being applied to or on behalf of oneself: e.g. bringing over for or on behalf of oneself or one’s project (hence my above examples with reference to “his camp”, “his hideout”, “her school” etc.).

II 6 is one of seven examples of how the LSJ observes how our word is used and translated across the literature. Here are those seven:

1 . . . bring to oneself, procure or provide for oneself, . . . devise, invent a means of shunning death . . . .

2 . . . of persons, bring into one’s country, bring in or introduce as allies . . .

3 . . . call them in as witnesses . . . introduce by way of quotation . . . adduce testimonies . . . .

4 . . . bring upon oneself . . . .

5 . . . bring with one . . . .

6 . . . bring over to oneself, win over . . . induce them to concede, Thucydides 5.41. . . . .

7 . . . put in place . . . .

Out of those seven different contextual middle voice meanings of ἐπάγω that are found throughout the literature, Schmidt zeroes in on that one instance from Thucydides 5.41 (see the footnote 147 above). “Induce” sounds sly, cunning. (Leave aside for a moment the fact that Aristotle used the word in the sense of “induce” when describing inductive argument or inductive reasoning.) And Schmidt calls attention to Thucydides describing how a group were “induced” to accept an agreement that was not ultimately in their interests. To reinforce his point he cites articles by Bermejo-Rubio and Cernuda.

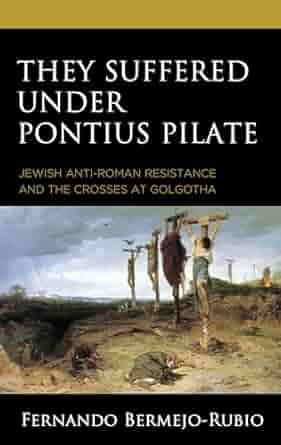

1. Bermejo-Rubio . . .

[T]he verb έπάγομαι [another form of ἐπάγω] already has a negative tinge (“bring something bad upon someone’) . . . , and in this context it may carry the meaning of “lead astray” or “seduce.”133 Interestingly, Josephus himself uses the verb έπάγομαι in this negative sense elsewhere (e.g., Ant. 1.207, 6.196,11.199, 17.327). All this is unfortunately overlooked or downplayed by the proponents of a ‘neutral’ text.134

133 See. e.g.. Bienert, Jesusbericht. 225; Potscher. “losephus Flavius,’ 33: and Stanton, “Jesus of Nazareth.” 170. The verb is used in 2 Peter 2:1 in connection with false prophets ‘bringing’ destruction on themselves.

134 Meier. “Jesus in Josephus.” 88. n.33 refers to the possible negative meaning of έχηγάγετο, but rules it out too hastily, not giving supporting references or further reasons for such rejection. What he translates as “And he won over many Jews and many of the Greeks’ is translated by others (e.g., Bammel, Morton Smith. Stanton) as “and he led astray.” (Bermejo-Rubio 2014, 354f)

Now this is finally beginning to look bad for the Jesus we read about in Josephus. Could it really be that the word should be meant to suggest that Jesus was “seducing” or “leading astray” his audience? We saw above that Josephus could use our word in a positive or neutral sense. Here, we are told, he is using it in a negative sense. So we will begin by looking at those other uses in Antiquities that are listed by Bermejo-Rubio. These are all said to convey a “negative sense” of the word – translated variously as “bringing”, “drew”, won over”. I add my comments in italics.

Abraham moved to Gerar of Palestine, bringing Sarah in the guise of a sister, pretending as before because of… (Antiquities 1.207)

[Ἅβραμος δὲ μετῴκησεν εἰς Γέραρα τῆς Παλαιστίνης ἐν ἀδελφῆς ἐπαγόμενος σχήματι τὴν Σάρραν, ὅμοια τοῖς πρὶν ὑποκρινάμενος διὰ τὸν…]

And David, always bringing God with him wherever he arrived… (Antiquities 6.196 – I don’t know why this instance is interpreted in a negative sense)

[Δαυίδης δὲ πανταχοῦ τὸν θεὸν ἐπαγόμενος ὅποι ποτ᾽ ἀφίκοιτο]

“And of all the women, Esther happened to excel—for that was her name—in beauty, and the charm of her face drew the gaze of onlookers even more strongly.” (Antiquities 11.199 – again I don’t know why this is listed as a negative meaning)

[πασῶν δὲ τὴν Ἐσθῆρα συνέβαινεν, τοῦτο γὰρ ἦν αὐτῇ τοὔνομα, τῷ κάλλει διαφέρειν καὶ τὴν χάριν τοῦ προσώπου τὰς ὄψεις τῶν θεωμένων μᾶλλον ἐπάγεσθαι.]

“…he had ceased from deceiving, but having come to Crete, he won over to the faith as many of the Jews as he came into contact with, and having become wealthy through their donations…” (Antiquities 17.327 – here a false prophet, Alexander, is winning over a following)

[… ἀπήλλακτο ἀπατᾶν, ἀλλὰ Κρήτῃ προσενεχθεὶς Ἰουδαίων ὁπόσοις εἰς ὁμιλίαν ἀφίκετο ἐπηγάγετο εἰς πίστιν, καὶ χρημάτων εὐπορηθεὶς δόσει τῇ ἐκείνων ἐπὶ]

For anyone thinking that except for 17.327 these are not strong examples of “bringing over” having a negative meaning, Bermejo-Rubio adds some scholarly references:

Bienert, Jesusbericht. 225;

Pötscher, “losephus Flavius,’ 33;

Stanton, “Jesus of Nazareth” 170.

Let’s look at those.

Bienert:

Original text: Denn diese Formulierung ἐπηγάγετο εἰς πίστιν Ἰουδαίους, ὁπόσοις εἰς ὁμιλίαν ἀφίκετο, legt den Gedanken nahe, daß Jesus in seinem Interesse, für seine Parteibildung, Anhänger geworben habe, während ein Christ doch die Vorstellung hat, daß Jesus die Menschen zu ihrem eigenen Heil für den Glauben geworben habe. Bei ἐπαγόμενος schwingt der Gedanke mit, das Zu-sich-Führen geschehe in irgendeinem Sinne zum persönlichen Vorteil des Subjekts.

For the formulation [“And he won over/brought over many of the Jews, and also many of the Greeks” suggests the idea that Jesus, in his own interest, for the formation of a faction, recruited followers — whereas a Christian would instead maintain that Jesus won people for their own salvation and for faith. With ἐπηγάγετο there is an implicit idea that this bringing-over served in some sense the personal advantage of the subject. (Bienert 1936, 225 – translation)

So Bienert says that a Christian would have written that Jesus won them over to the faith. But Bienert runs into a problem here because Josephus did indeed say, explicitly, that a false prophet, Alexander, won over the following “into the faith” (εἰς πίστιν). So how could a Christian author have written that Jesus was winning over followers to the faith in a good sense? Bienert says that the word for “won over” still had a bad implication simply because it is in the middle voice and therefore it meant that Alexander – and also Jesus – were motivated by devious self-interest. This is butchery of the Greek. Middle voice does not imply a negative motivation. It implies some person does something directly or indirectly for or on behalf of the same person, regardless of motive – such as when Jesus called disciples to follow him. Would a Christian really think such an action as Jesus calling people to follow him, saying “Follow me”, was a deviously self-serving action on the part of Jesus?

Pötscher:

For Pötscher, the word ἐπηγάγετο should be linked with the following sentence, “He was the Christ”, not with the earlier words about his followers. In this case, the word should be translated as “put forward” the idea that He was the Christ. Compare the third meaning in the LSJ II 6 reference above.

Original: έπηγάγετο paßt sogar zu dem unmittelbar Folgenden besser. . . . Ich schlage vor: … έπηγάγετο, ότι ό Χρίστος ούτος ειη [=”He brought him forward, saying that this was the Christ.”]. Die Ände rung ist sehr leicht; εΐη mußte der Christ in ην verbessern, dann konnte das kurze Wort δτι leicht ausfallen.

“ἐπηγάγετο actually fits better with what immediately follows. . . . I propose [the original text read as . . . “He brought him forward, saying that this was the Christ.”]: … ἐπηγάγετο, ὅτι ὁ Χριστὸς οὗτος εἴη. The change is very slight; the Christian copyist had to correct εἴη to ἦν, and then the short word ὅτι could easily drop out. . . . (Pötscher 1975, 33f – translation)

If the primary source material does not support the hypothesis it appears to be accepted practice to hypothesize a change to the source to make it fit. But even so, this particular argument has nothing to do with the notion that the word ἐπηγάγετο conveys a negative meaning. If there is anything negative here it lies in the context, presumably of making a false claim. One can hardly say that the word meaning “put forward” by itself is negative or positive.

Stanton:

Let us start with the final verb, ἐπηγάγετο, translated by Feldman as “he won over,” and by Meier as “he gained a following among.” . . . Bauer’s lexicon gives “bring on” as the meaning of ἐπάγω, and notes that in figurative usage it usually has the sense “bring something bad upon someone.”19 Hence ἐπηγάγετο in the Testimonium can be understood as “brought trouble to,'” or even “seduce, lead astray.”20

19 BAGD 281. Josephus Life 18 is a good example of the verb in this [negative] sense. “Win over” is attested in Thucydides and Polybius (see LSJ) and Chrysostom (see G. W. H. Lampe, Patristic Greek Lexicon), but the verb is rarely used with this positive sense.

20 Bammel notes that significatio seditionis is possible for ἐπάγομαι (“Testimonium Flavianum,” Judaica, 179-81). Meier acknowledges that this is “a possible, though not necessary, meaning of the verb,” but does not give supporting references or reasons for rejecting this translation (“Jesus in Josephus,” 88 n. 33). M. Smith, Jesus the Magician (London: Victor Gollancz, 1978) 178, translates “lead astray” and claims that this sense is implied by the Greek text. (Stanton 1994, 170)

Look first at Bauer’s Lexicon. Yes, this lexicon does say that the word in the middle voice can have the figurative use meaning of “bring something [mostly bad] upon someone”. The only difficulty here, however, is that in Josephus’s passage about Jesus he is not using the word figuratively!

Bauer gives examples of the figurative use:

Hesiod, Works and Days 240

But upon them from heaven the son of Cronos brought a great bane —

famine and plague together — and the people perished.

τοῖσιν δ᾽ οὐρανόθεν μέγ᾽ ἐπήγαγε πῆμα Κρονίων

λιμὸν ὁμοῦ καὶ λοιμόν: ἀποφθινύθουσι δὲ λαοί.

Here is the complete Bauer reference where I highlight some other sources with the figurative use:

ἐπάγω 1 aor. ptc. έπάξας (Bl-D. §75 w. app.; Mit -H. 226: Rob. 348); 2 aor. ἐπἠγαγον (Hom. +; inscr., Philo.9 pap., LXX, Philo, Joseph., Test. 12 Patr.) bring on; fig. bring someth. upon someone, mostly someth, bad τινἰ τι (Hes., Op. 240 πῆμά τινi έ. al.; Dit., Or. 669, 43 πολλοῖς ἐ. κινδύνους; PRyl. 144, 21 [38 AD] . . . μοι ἐ.αἰτίας; Bar 4:9 10,14, 29; Da 3: 28, 31; Philo, Mos. 1, 96; Jos. Vi. 18; Sib. Or. 7, 154) κατακλυσμόν κόσμῳ έπάξας 2 Pt 2:5 (cf. Gen 6: 17; 3 Macc 2: 4 of the deluge ἐπάγαγὼν αὐτοῖς ἀμέτρητου ὗδωρ). λύπην τῷ πνεύματι bring grief upon the spirit Hm 3: 4. ἑαυτοῖς ταχινὴν ἀπώλειαν bring swift destruction upon themselves Pt 2: 1 (cf. ἑαυτοῖς δουλείαν Demosth. 19, 259). Also ἐπί τινά τι (Ex 11:1; 33: 5; Jer 6:19; Ezk 28:7 and oft.) ἐφ’ ἡμάᾶς τὸ αἶμα τ. ἀνθρώπου τούτου bring this man’s blood upon us Ac 5:28 (cf. Judg 9: 24 B ἐπαγαγεῖν τὰ αἵματα αὐτῶν, τοῦ θεῖναι ἐπὶ Ἀβιμελεχ, ὃs ἀπέκειvev αὐτούς), έ. τισὶ διωyμὸv κατά τινος stir up, within a group, a persecution against someone Ac 14: 2 D. M-M. (Bauer and Arndt 2021, 281 — I don’t think there is any instrinsic negative shift in meaning to ἐπάγω because of the figurative use: rather, I suspect that it is more common to speak of calamaties being brought upon us than it is good things.)

The Bauer lexicon and Stanton point to another figurative use of the word in Josephus’s Life, section 18, and again it is definitely with a negative sense:

[and desired them] not rashly, and after the most foolish manner, to bring on the dangers of the most terrible mischiefs upon their country, upon their families, and upon themselves.

καὶ μὴ προπετῶς καὶ παντάπασιν ἀνοήτως πατρίσι καὶ γενεαῖς καὶ σφίσιν αὐτοῖς τὸν περὶ τῶν ἐσχάτων κακῶν κίνδυνον ἐπάγειν.

But there is nothing figurative about Josephus’s use of the word relating to Jesus. Jesus is not bringing down plagues or war or terror or even riches and rewards. He is literally, not figuratively, bringing people to himself by means of his teaching.

Stanton offers other examples, Polybius and Thucydides, where the word is used and notes it is there it is used with a positive sense. We can note that the difference is with Polybius and Thucydides we meet a literary and not a figurative use. Stanton can only comment that “the verb is rarely used with this positive sense”. Presumably he is thinking of the many figurative usages.

Notice how positive in meaning Polybius’s use really is:

Polybius 7:14.4, cited in the LSJ (Liddell Scott Jones Greek-English Lexicon) reference:

. . . having employed Aratus as guide in general matters, he neither wronged nor even caused distress to any of those on the island, but held all the Cretans under his control, and brought all the Greeks over to goodwill toward himself through the dignity of his character.

. . . καὶ γὰρ ἐπ᾽ ἐκείνων Ἀράτῳ μὲν καθηγεμόνι χρησάμενος περὶ τῶν ὅλων, οὐχ οἷον ἀδικήσας, ἀλλ᾽ οὐδὲ λυπήσας οὐδένα τῶν κατὰ τὴν νῆσον, ἅπαντας μὲν εἶχε τοὺς Κρηταιεῖς ὑποχειρίους, ἅπαντας δὲ τοὺς Ἕλληνας εἰς τὴν πρὸς αὑτὸν εὔνοιαν ἐπήγετο διὰ τὴν σεμνότητα τῆς προαιρέσεως.

So we have a non-figurative use of the word and one can scarcely imagine a more positive meaning: “brought all the Greeks over to goodwill toward himself through the dignity of his character”.

The same reference, LSJ, gives this example of Thucydides’ use, also singled out by Stanton that he concedes also carries positive innuendo:

Thucydides 5:45

Upon the envoys speaking in the senate upon these points, and stating that they had come with full powers to settle all others at issue between them, Alcibiades became afraid that if they were to repeat these statements to the popular assembly, they might gain the multitude, and the Argive alliance might be rejected,

καὶ λέγοντες ἐν τῇ βουλῇ περί τε τούτων καὶ ὡς αὐτοκράτορες ἥκουσι περὶ πάντων ξυμβῆναι τῶν διαφόρων, τὸν Ἀλκιβιάδην ἐφόβουν μὴ καί, ἢν ἐς τὸν δῆμον ταῦτα λέγωσιν, ἐπαγάγωνται τὸ πλῆθος καὶ ἀπωσθῇ ἡ Ἀργείων ξυμμαχία.

This is a good time to look at another passage in Thucydides, one that Schmidt identifies as conveying a negative sense of “inducing” (with a tinge of deceit) the Spartans to agree to a foolish treaty.

Thucydides 5.41.2

Arrived in Sparta, the Argive representatives discussed with the Spartans the conditions for a treaty. . . . The Spartans . . . said that, if Argos would agree, they were prepared to accept the same terms as in the previous treaty. Nevertheless the Argive representatives managed in the end to get the Spartans to agree to the following arrangement . . . (Rex Warner’s translation)

καὶ οἱ πρέσβεις ἀφικόμενοι αὐτῶν λόγους ἐποιοῦντο πρὸς τοὺς Λακεδαιμονίους ἐφ᾽ ᾧ ἂν σφίσιν αἱ σπονδαὶ γίγνοιντο. καὶ . . . ἔπειτα δ᾽ οὐκ ἐώντων Λακεδαιμονίων μεμνῆσθαι περὶ αὐτῆς, ἀλλ᾽, εἰ βούλονται σπένδεσθαι ὥσπερ πρότερον, ἑτοῖμοι εἶναι, οἱ Ἀργεῖοι πρέσβεις τάδε ὅμως ἐπηγάγοντο τοὺς Λακεδαιμονίους ξυγχωρῆσαι . . .

Whatever one thinks of the wisdom of making the treaty, the use of the Greek word for “bringing over/getting to agree/induced/winning over” is describing an event of mutual negotiations, of diplomatic statecraft. There is no inherent suggestion that the word implies any deceit.

Finally, Stanton directs us to Chrysostom. Following Lampe’s A Patristic Greek Lexicon we find the passage is in the 28th Homily to Hebrews:

Chrysostom Homily to Hebrews 28, 263B

Tell me: who attracts more attention in the marketplaces—the one who brings along many, or the one who brings along few?

But of the one who brings along few, is she not the one who appears more modest and less conspicuous?

Εἰπέ μοι· τίς ἐπιστρέφει τοὺς ἐπ’ ἀγορὰς, ἡ πολλοὺς ἐπαγομένη, ἢ ἡ ὀλίγους;

ταύτης δὲ τῆς ὀλίγους ἐπαγομένης, οὐχὶ ἡ μᾶλλον ἀπρόοπτος φαινομένη;

As Stanton notes, there is no negative meaning instrinsic to the word in question here.

Thus far we have followed Schmidt’s references to the LSJ, the Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek, a passage in Thucydides and his appeal to an article by Bermejo-Rubio. We conclude with a look at the article by Cernuda that he also appeals to.

2. Cernuda . . .

Original: También ἔπάγομαι se podría haber empleado en mal sentido80. Así se ha sostenido también que era el caso81. . .

ἐπάγομαι itself could also be used in a negative sense80. It has thus also been argued that such is the case here81 . . . (Cernuda 1997, 373f – translation)

I learned long ago to always check the footnotes. Devils often lurk in such details. And we find them once again here. These devils are actually denying Schmidt his interpretation of “brought over”. Continuing with the translation, and with my own bolded highlighting added:

Original: 80 Cf. infra. Bammel (“Zum TF”, nota 25) atribuye a K. Linck ejemplos de ἔπάγομαι con significación negativa; pero los cuatro casos que éste presenta de Josefo son absolutamente inofensivos, y ésa era su intención, pues lo que hizo Linck, en contra de lo que supone Bammel, es impugnar la pretensión de los que supponere student significationem seditionis. […] Sed hic sensus eius verbi nulla re probatur, nedum postuletur (De antiquissimis veterum quae ad Jesum Nazarenum spectant testimoniis [Giessen 1913] 24).

81 Es la postura que adoptó Reinach, perdiendo la debida imparcialidad semántica: “le verbe ἐπηγάγετο ‘il séduisit’, qui ne s’emploie qu’en mauvaise part et raille l’accusation de séduction portée contre Jésus […]; ἐπηγάγετο = pellicere […] un des vestiges les plus caractéristiques du ton hostile de la rédaction primitive” (“Josè”, 7 y 11). La reacción de Pelletier no pudo ser más justa: “En réalité, la nuance péjorative n’est habituelle que pour le verbe pellicere, employé ici par la traduction latine anonyme, et non pour le verbe grec que figure dans Josèphe” (“Témoignage”, 190).

80 Cf. infra. Bammel (“Zum TF,” note 25) attributes to K. Linck examples of ἐπάγομαι with negative meaning. But the four examples Linck gives from Josephus are completely irrelevant, and that was his intention: for what Linck did—contrary to what Bammel supposes—was to refute the claim of those who studiously assume a seditious meaning for the verb: “But this meaning of the verb is not supported by any evidence, nor is it required” (De antiquissimis veterum quae ad Jesum Nazarenum spectant testimoniis, Giessen 1924, p. 13).

81 This is the position adopted by Reinach, who lost proper semantic neutrality: “The verb ἐπηγάγετο, ‘he seduced,’ which is only ever used pejoratively, mocks the accusation of seduction leveled against Jesus […]. ἐπηγάγετο = pellicere [to seduce] is one of the most characteristic remnants of the hostile tone of the primitive redaction” (“Josè”, pp. 7 and 11). Pelletier’s response could not have been more justified: “In reality, the pejorative nuance is habitual only for the Latin verb pellicere, used here by the anonymous Latin translator, and not for the Greek verb found in Josephus” (“Témoignage,” p. 190).

Cernuda’s article thus actually contradicts Schmidt’s claim that Josephus had a negative intent in mind when he used the word of Jesus. It appears Schmidt failed to notice Cernuda’s devilish footnotes.

Bibliography

- Bauer, Walter, William Arndt, Felix Wilbur Gingrich, and Frederick W. Danker. 1979. A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and Other Early Christian Literature 2nd Ed. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bermejo-Rubio, Fernando. 2014. “Was the Hypothetical ‘Vorlage’ of the ‘Testimonium Flavianum’ a ‘Neutral’ Text? Challenging the Common Wisdom on ‘Antiquitates Judaicae’ 18.63-64.” Journal for the Study of Judaism in the Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman Period 45 (3): 326–65.

- Bienert, Walther. 1936. Der älteste nichtchristliche Jesusbericht, Josephus über Jesus : unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des altrussischen “Josephus.” Halle : Akademischer Verlag.

- Cernuda, Antonio Vicent. 1997. “El Testimonio Flaviano, Alarde De Solapada Ironía.” Estudios Bíblicos 55 (3, 4): 355–85, 479–508.

- Chrysostomi, Joannnis. 1862. In Dive Pauli Epistolam ad Hebraeos Homiliae. Oxford: Parker. http://archive.org/details/chrysostom_pauline_homilies_field_vol_7.

- Ehrman, Bart D. 2013. Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth. New York: HarperOne.

- Hurtado. 2012. “On Competence, Scholarly Authority, and Open Discussion (and ” the Data “).” Larry Hurtado’s Blog (blog). August 2, 2012. https://larryhurtado.wordpress.com/2012/08/02/on-competence-scholarly-authority-and-open-discussion/.

- Lampe, G.W.H. ed. 1961. A Patristic Greek Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Liddell, Henry George, and Robert Scott. 1996. A Greek–English Lexicon. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Montanari, Franco. 2015. The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek. Leiden: Brill.

- Schmidt, T. C. 2025. Josephus and Jesus: New Evidence for the One Called Christ. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Continues with Part 5 (pending)

Like this:

Like Loading...