I have written often about history, the nature of history, the history of historical writings, and historical methods. Very often the context of those posts has been biblical scholarship that falls short of meeting the basic standards of scholarly historical inquiry as it is typically found in history and classics departments. Occasionally one comes across a biblical scholar (e.g. Scot McKnight) who does bring up the names of historians in “nonbiblical fields” (e.g. Geoffrey Elton, E.H. Carr) but too quickly the main point of difference is bypassed even in those discussions. To find biblical historians who have taken up the methods of other historians — beginning with primary evidence and moving cautiously from there to secondary evidence — one turns to those unfortunately labelled “minimalists” in the studies of ancient Israel.

This post is a response to some specific claims about historical methods by Justin Meggitt, another scholar of religion, in his 2019 article, “More Ingenious than Learned’? Examining the Quest for the Non-Historical Jesus”. Meggitt, I hope to demonstrate, has also misinterpreted the way nonbiblical historians work and misapplied some of their methods to the question of historical Jesus studies — even while attempting to better inform his biblical scholar peers. In so doing I trust a more valid way forward will become clearer.

105

-

- V. Chaturvedi, ed., Mapping Subaltern Studies and the Postcolonial (London: Verso, 2012);

- S. G. Magnússon and I. M. Szijártó, What is Microhistory?: Theory and Practice (London: Routledge, 2013);

- A. I. Port, ‘History from Below, the History of Everyday Life, and Microhistory’, ed. J. Wright, International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences (Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2015) 108–13.

Indeed, the lack of conventional historical training on the part of biblical scholars may well be evident in the failure of any scholar involved in discussing the Christ-myth debate to mention any long-established historiographical approaches associated with the study of the poor in the past, such as History from Below, Microhistory or Subaltern Studies,105 approaches that might help us determine what kind of questions can be asked and what kind of answers can reasonably be expected to given, when we scrutinise someone who is depicted as coming from such a non-elite context.

(Meggitt, 22. Bolded highlighting is my own in all quotations)

History from Below is taken from the title of an encyclopedia article, “History from Below, the History of Everyday Life, and Microhistory”, by A. I. Port. (The link is to the same article on academia.edu.) According to Port historians who work at this level

. . . dramatically reduce the scale of their historical investigation, confining it to a single individual, small community, or seemingly obscure event which is then subject to painstaking microscopic analysis involving an intensive study of the available documentary material.

Port cites some examples:

Such histories usually fall into one of two categories: the ‘episodic’ and the ‘systematic’ (Gregory, 1999: 102). The first type, which tends to take a narrative approach and rely heavily on ‘thick description,’ focuses on a single, spectacular episode or event usually involving one person or a small group of individuals – such as

- the investigation of a heretical sixteenth century Italian miller by Inquisition officials (Ginzburg, 1980),

- the elaborately staged murder of dozens of cats by disgruntled apprentice printers in Paris in the 1730s (Darnton, 1984),

- or an antisemitic riot incited by accusations of blood libel in a small Prussian town in the early twentieth century (Smith, 2002).

The other type assiduously reconstructs the complex web of familial and extrafamilial social relations in a small community. Prominent examples include

- Giovanni Levi’s study of social interaction in a village in the Piedmont in the 1690s – “a banal place and an undistinguished story,” in the words of the author (Levi, 1988) –

- and David Sabean’s dense studies of property, production, and kinship in the southern German village Neckarhausen from 1700 to 1870 (Sabean, 1990, 1998).

(Port, 108, formatting is my own in all quotations)

Surely, you are probably thinking, the historian must have primary and secondary sources on which to base any research into subjects like those. Indeed, they do. History from Below is not about subjects for whom we lack sources; it is a history that works with sources for “commoners”, everyday people, as opposed to the “great names” and institutions and parties that we normally turn to to “do history”. Another reference cited by Meggitt is What is Microhistory?: Theory and Practice by S. G. Magnússon and I. M. Szijártó, which contains a chapter on “Refashioning a Famous French Peasant”. It addresses method and sources for a historical inquiry into the sixteenth-century story of Martin Guerre and his wife, Bertrande de Rols. (Martin Guerre went missing and an imposter subsequently appeared to take his place. You know the story if you have seen the film Sommersby.) The sources available to historians on this person and his community are

-

- court documents and correspondence penned by Judge Jean de Coras;

- Histoire Admirable by Guillaume Le Sueur who based his story on notes by another judge involved in the case.

The poor villagers did not usually leave behind written records themselves but historians do have access to

reports by police and church officials, teachers, physicians, and factory inspectors; personal correspondence and travelogues; parish registers, wills, notarial records, and protocols.

(110)

We have nothing comparable for the study of Jesus or any of his presumed disciples.

Meggitt advises biblical scholars that they should be aware of the problems with this sort of “microhistory”. In principle, that is true. The nature of the evidence will always dictate what questions can be asked in the expectation of useful answers. But one does have to note that there is simply no primary source material of the kinds addressed in the three sources Meggitt cites for “microhistory” or “history from below” that is comparable to sources available for Christian origins and Jesus or any of his disciples. So the advice to be “aware of problems” of using primary sources for a person from the lower classes is misplaced in the context of historical Jesus studies.

106

-

-

- Knapp, Robert. 2011. Invisible Romans: Prostitutes, Outlaws, Slaves, Gladiators, Ordinary Men and Women… The Romans That History Forgot. London: Profile Books.

107

- Thompson, E. P. 1966. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Vintage.

-

For example, given that most human beings in antiquity left no sign of their existence, and the poor as individuals are virtually invisible,106 all we can hope to do is try to establish, in a general sense, the lives that they lived. Why would we expect any non-Christian evidence for the specific existence of someone of the socio-economic status of a figure like Jesus at all? To deny his existence based on the absence of such evidence, even if that were the case, has problematic implications; you may as well deny the existence of pretty much everyone in the ancient world. Indeed, the attempt by mythicists to dismiss the Christian sources could be construed, however unintentionally, as exemplifying what E. P. Thompson called ‘the enormous condescension of posterity’107 in action, functionally seeking to erase a collection of data, extremely rare in the Roman empire, that depicts the lives and interactions of non-elite actors and seems to have originated from them too.

(Meggitt, 24f)

“For example” — that introduction is misplaced as a follow on from a discussion of “microhistory” or “history from below” by Chaturvedi, Magnússon and Port. Those three authors are addressing not “virtually invisible” persons, but persons of whom we have enough primary sources to write serious history even though they were not elites. The preceding paragraph was referring to a type of history includes the bringing to light those “poor as individuals” for whom we do have “signs of their [individual, personal] existence.” Knapp, whom Meggitt now cites at #106, is writing a quite different kind of history. Knapp is not an example of a historian doing the sort of history just described as “microhistory”. Knapp is doing something very different. He is doing another form of “macrohistory”:

“For example” — that introduction is misplaced as a follow on from a discussion of “microhistory” or “history from below” by Chaturvedi, Magnússon and Port. Those three authors are addressing not “virtually invisible” persons, but persons of whom we have enough primary sources to write serious history even though they were not elites. The preceding paragraph was referring to a type of history includes the bringing to light those “poor as individuals” for whom we do have “signs of their [individual, personal] existence.” Knapp, whom Meggitt now cites at #106, is writing a quite different kind of history. Knapp is not an example of a historian doing the sort of history just described as “microhistory”. Knapp is doing something very different. He is doing another form of “macrohistory”:

I seek to uncover and understand what life was like for the great mass of people who lived in Rome and its empire. . . .

Ancient evidence comes in two types: the one intentionally provided and the other incidentally. The first is generally irrelevant to our purpose, but the second can be crucial. An elite author setting out, for example, to write on the Roman wars of expansion, will sometimes include contextual details and bits of information which, when combined with other evidence, begin to create a picture of ordinary people. The experience of ordinary people has no direct voice in the histories the Romans have left us. Yet sometimes it is possible to garner insights into the lives of the invisible people even where none was intended and to amplify these by deploying perspectives and evidence from a variety of other sources.

(Knapp, 7f)

That’s very different from a “people’s history” in the sense discussed in the preceding paragraph. Knapp’s history of “ordinary people” (as he calls his demographic target of study) leaves no room whatever for a study of “a single individual, small community, or seemingly obscure event” (Port). As the article stands it appears that Meggitt has confused two quite distinct types of history. This is not a promising start for advancing historical Jesus studies.

So when Meggitt goes on to rhetorically ask

Why would we expect any non-Christian evidence for the specific existence of someone of the socio-economic status of a figure like Jesus at all?

he has already given us the answer but has turned his back on it because he has confused history of masses with micro or people’s history. To do “history from below” on Jesus a “micro-historian” will expect to find, as he or she does for other low-class persons, contemporary evidence preserved by literate classes about a person who was attracting a lot of attention among “the masses”. Literate classes have servants and contact with markets and will learn of any person making a name for themselves. Josephus notes quite a few of them, often with disgust. So do other Roman elites. We know, for example, interesting details about Cicero’s slave, Tiro.

Meggitt’s misguided citations of other historians continue when he suggests mythicists are guilty of the renowned historian E. P. Thompson’s charge of “enormous condescension of posterity”. This is an unfortunate reference because it misreads Thompson’s context and full scope of his work. Here is Thompson’s phrase in the context of the complete sentence:

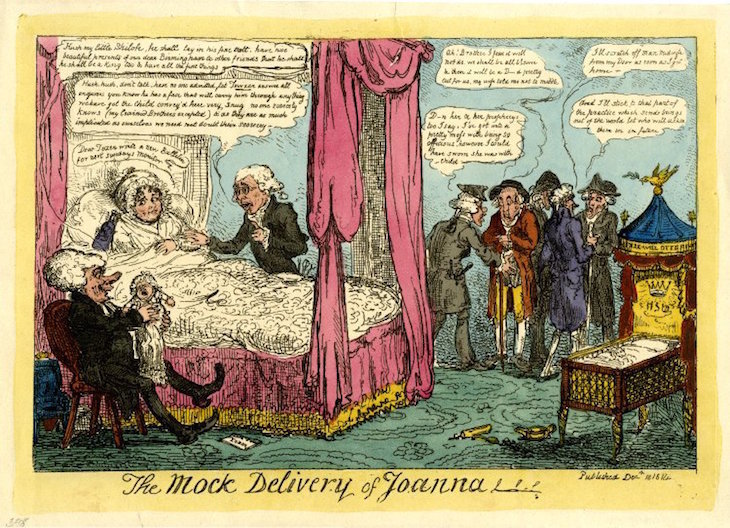

I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the “obsolete” hand-loom weaver, the “utopian” artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott, from the enormous condescension of posterity.

(Thompson, 12)

If there was any name in that sentence analogous to Jesus it is Joanna Southcott. It is not Joanna Southcott that Thompson is seeking to rescue “from the enormous condescension of posterity” — it is the anonymous croppers and weavers who followed her! Joanna Southcott is a figure well preserved in primary sources even though she was a peasant’s daughter and domestic servant. We have just as much reason to expect a comparable figure to survive a mention somehow somewhere in contemporary sources. Thompson explains,

But the most startling evidence of a “despiritualized fury” is to be found in the movements surrounding — and outliving — the greatest Prophetess of all, Joanna Southcott. It was in1801 that her first cranky prophetic booklet was published, The Strange Effects of Faith. And the general climate of expectant frenzy is shown by the rapidity with which the reputation of the Devon farmer’s daughter and domestic servant swept the country. Her appeal was curiously compounded of many elements. There was the vivid superstitious imagination of the older England, especially tenacious in her own West Country. “The belief in supernatural agency”, wrote the Taunton Courier in 1811,

is universally prevalent throughout the Western Counties, and very few villages there are who cannot reckon upon at least one who is versed in “Hell’s Black Grammar”. The Samford Ghost, for a while, gained its thousands of votaries. . . .

There was the lurid imagery and fervour of the Methodist communion, to which (according to Southey) Joanna had been “zealously attached”. There was the strange amalgam of Joanna’s own style, in which mystic doggerel was thrown down side by side with shrewd or literal-minded autobiographical prose — accounts of childhood memories, unhappy love affairs, and encounters between the stubborn peasant’s daughter and disbelieving parsons and gentry. There was, above all, the misery and war-weariness of these years, and the millennarial expectancy, of a time when the followers of [Richard] Brothers still lived daily in the hopes of fresh revelation—a time when:

One madman printed his dreams, another his day-visions; one had seen an angel come out of the sun with a drawn sword in his hand, another had seen fiery dragons in the air, and hosts of angels in battle array. . . . The lower classes . . . began to believe that the Seven Seals were about to be opened. . . .

Joanna was no Joan of Arc, but she shared one of Joan’s appeals to the poor: the sense that revelation might fall upon a peasant’s daughter as easily as upon a king. She was acclaimed as the true successor to Brothers, and she gathered around her an entourage which included several educated men and women. (If Blake’s prophetic books may be seen, in part, as an idiosyncratic essay in the margin of the prevailing prophetic mood, his acquaintance William Sharp, also an engraver and former “Jacobin”, gave to Joanna his complete allegiance.) But Joanna’s appeal was felt most strongly among working people of the west and north—Bristol, south Lancashire, the West Riding, Stockton-on-Tees. . . .

It is probable that Joanna Southcott was by no means an impostor, but a simple and at times self-doubting woman, the victim of her own imbalance and credulity. . . .

The first frenzy of the cult was in 1801-4; but it achieved a second climax in 1814 when the ageing Joanna had an hysterical pregnancy and promised to give birth to “Shiloh”, the Son of God. In the West Riding “the whole district was infested with bearded prophets”, while Ashton, in Lancashire, later became a sort of “metropolis” for the “Johannas” of the north. When the Prophetess died in the last week of 1814, tragically disillusioned in her own “Voice”, the cult proved to be extraordinarily deep-rooted. Successive claimants appeared to inherit her prophetic mantle, the most notable of whom was a Bradford woolcomber, John Wroe. Southcottian derivatives passed through one aberration after another, showing themselves capable of sudden flare-ups of messianic vitality . . . .

(Thompson, 383-87)

I have highlighted a few details that may be seen as strikingly similar to what is often thought about Jesus and the movement arising from his activity. Those sorts of peasants, “nobodies”, did attract contemporary documentation and have become part of historical records. When Thompson speaks of rescuing those lost to history, he is speaking of the anonymous followers of Joanna Southcott. A figure like Jesus, even on a “minimal historicity” level that still allows room for explaining the movement arising from his life is the sort of figure one expects to find some contemporary record of. Meggitt’s point is overturned by the full quotation and historical work of Thompson itself.

To return to a point made earlier by Meggitt:

Although this interest in ‘history’ is hardly surprising as we are dealing with historicity, arguments about ‘history’ in this debate are not just about professional expertise or about technical disagreements about method but indicative of a deliberate rhetorical strategy too. Many claims to being a historian are about self-presentation, about being the person who can legitimately claim those somewhat antiquated but still significant mantles of objectivity or neutrality, something , for example, evident in Ehrman’s words: ‘Jesus existed, and those vocal persons who deny it do so not because they have considered the evidence with the dispassionate eye of the historian, but because they have some other agenda that this denial serves. From a dispassionate point of view, there was a Jesus of Nazareth.’ But New Testament scholars should concede that the kind of history that is deemed acceptable in their field is, at best, somewhat eccentric. Most biblical scholars would be a little unsettled if, for example, they read an article about Apollonius of Tyana in a journal of ancient history that began by arguing for the historicity of supernatural events before defending the veracity of the miracles ascribed to him yet would not be unsurprised to see an article making the same arguments in a journal dedicated to the study of the historical Jesus.

Rarely (but not never) have I seen biblical scholars demonstrate a clear understanding of how “history works” in history departments (as distinct from theology and religion departments). There are dozens of posts setting out the differences between the two on this blog and I see that there is an annotated bibliography of such posts that I am long overdue to complete. I have posted my view of how valid historical inquiry is undertaken and it is grounded in the precepts and discussions of a good number of historians, many of them prominent in their fields. One famous historian who did directly engage with the methods of biblical scholars in their study of Jesus was Moses I. Finley. One of the posts about his views is at An Ancient Historian on Historical Jesus Studies, — and on Ancient Sources Generally. For other posts addressing the specifics: How do historians decide who was historical, who fictional?, Ancient History, a “Funny Kind of History”. (Finley is certainly not alone.)

Meggitt does not strengthen his point by raising Bart Ehrman’s book Did Jesus Exist? given its many unfortunate indications that he failed to even read some of the authors and arguments he spoke about and his highlighting some of the worst and most fallacious methods of “historical research” found in biblical studies. Historians in other departments do not attempt to investigate historical persons through anonymous and unprovenanced (certainly not hypothetical) sources. (Such sources do have a value, but that is for understanding the beliefs, values, and literary culture of authors and audiences.)

Meggitt’s point about biblical scholars accepting reports of miracles and searching for ways to rationalize them is justified. But there is a more serious problem he overlooks: anonymous documents of uncertain dates that do not attempt to win the confidence of readers in the same way other historians of the day attempted to do so — by stating their credentials and citing their sources and expressing scepticism about reports of the supernatural (Luke’s prologues notwithstanding) — should not be naively assumed to be based on oral traditions preserving (with elaboration) historical persons and events. That is even moreso when those same documents can be seen to be sourced intertextually from other revered literature.

Justin Meggitt has taken some small steps in the right direction. But as I have hoped to demonstrate above, some wobbles are still there and hopefully they will be overcome in time.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. 2012. “Introduction.” In Mapping Subaltern Studies and the Postcolonial, edited by Vinayak Chaturvedi, Reprint edition, vii–xix. London ; New York: Verso.

Knapp, Robert. 2011. Invisible Romans: Prostitutes, Outlaws, Slaves, Gladiators, Ordinary Men and Women… The Romans That History Forgot. London: Profile Books.

Magnússon, Sigurður Gylfi, and István M. Szijártó. 2013. What Is Microhistory? London ; New York: Routledge.

Meggitt, Justin. 2019. “‘More Ingenious than Learned’? Examining the Quest for the Non-Historical Jesus.” New Testament Studies 65 (4): 443–60. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0028688519000213.

Port, Andrew I. 2015. “History from Below, the History of Everyday Life, and Microhistory.” International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 108–13.

Thompson, E. P. 1966. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Vintage.

Neil Godfrey

Latest posts by Neil Godfrey (see all)

- What Others have Written About Galatians (and Christian Origins) – Rudolf Steck - 2024-07-24 09:24:46 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Alfred Loisy - 2024-07-17 22:13:19 GMT+0000

- What Others have Written About Galatians – Pierson and Naber - 2024-07-09 05:08:40 GMT+0000

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

“Why would we expect any non-Christian evidence for the specific existence of someone of the socio-economic status of a figure like Jesus at all?”

Let me guess. Because of all the wonders he accomplished witnessed by masses of people…..?

even with none of that — just as an interesting teacher attracting attention, critical of authorities, whose followers expanded the game with more of the same.

Indeed.

Permit me add to the bibliography, the deliberate riff on Carr by the Princeton historian of Early Modern History, Anthony Grafton. His work, What was History: The Art of History in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: 2007). This is a masterful study of the ars historica.

I like Anthony Grafton’s work and you have made me feel terrible for not having read What Was History. I am downloading it now and will add it to my file of other works on philosophy and methods of history. As for the biblio in my posts, I only list those cited in the post itself. Maybe on this topic I will create a more comprehensive bibliography and add it to my slowly emerging page (right hand column) of annotated links to all my posts on history. I’ll be sure by that time to have read Grafton’s book. Thanks again.

The mysterious thing to me is there was, supposedly, quite an extensive community of “Christians” formed up after the death of Jesus (if the stories are to be believed). Some of these followers were of considerable wealth. Since these were Jews or former Jews, they understood the role of scripture, so how is it that a wealthy believer, or the community as a whole, didn’t hire a scribe to debrief every one who spend any time with God Incarnate? Wouldn’t you have pumped every one of the disciples, apostles, family members for every little thing Jesus said or did while here? How is it that this didn’t happen? Wouldn’t God’s words or the Son of God’s words be something people would not want to lose? Then would not those documents be copied and copied and copied to be distributed to Christian communities all over the region?

No?

All quite so. I think Meggitt would reply, however, that the disciples didn’t appreciate how great Jesus was until after he was dead, or “resurrected” in some sense. This scenario, of course, only opens up another whole new set of implausibilities posited to explain Christian origins.

ON PAGANS, JEWS, and CHRISTIANS — Arnaldo Momigliano, 1987

Chapter 1: Biblical Studies and Classical Studies

Simple Reflections upon Historical Method

p.3

“Principles of Historical research need not be different

from criteria of common sense. And common sense teaches

us that outsiders must not tell insiders what they should

do. I shall therefore not discuss directly what biblical

scholars are doing. They are the insiders.”

Two more a propos quotes from the same chapter:

and one that is embarrassingly necessary in certain areas of biblical studies:

Who said Jesus was poor, or not an elite?

Oh, that’s right, the Gospels.

You are using a preconceived idea from a source you don’t see as historically accurate to define a person you believe to be mythical. Not very sound historical analysis, don’t you think?

And btw, the difference between historical accounts of Southcott and a lack of same for Jesus is that he was presumed to be the rightful king of Judea during the reign of Herod and the Roman occupation, where making such a claim could be a death sentence (and ultimately was). There are non-biblical accounts of Jesus that are either written allegorically or that hide his identity for that reason. But scholars like yourself refuse to analyze the data. Again, not very sound historical analysis.

It is imperative that historians begin any analysis of historical data without any preconceived ideas. That should be Rule#1.

If an idea is taken from a source, the Gospels, as you say it is, then it is not by definition a “preconceived idea” that is read into the gospels. Rule #1 is not being violated.

If Jesus were recognized by significant numbers of people as the rightful king then we have even more reason to expect to find him mentioned in a contemporary source. There was no risk to a historian or anyone writing about a criminal being punished for his crime.

Thanks for censoring my reply.

It seems that you only post the ones you think you can refute and delete the ones you can’t.

Great scholarship! Tell me, how can you set yourself up as the arbiter of historical method when you make mistakes like the above article and you censor posts that either disagree with you or convincingly refute your mythicist theories?

Amazing.

No, David. I allowed your initial comment to appear when I was caught in a vulnerable moment wondering if I had been too harsh in my treatment of some commenters. I copy your reply here to make it clear what it was to readers what I channelled off into the trash. After many attempts to patiently work through with you on some of your past comments I came to the point of thinking you many be incapable of meaningfully reflecting on why you believe no-one else agrees with you. I am at a loss to know who to engage productively in a discussion with you. You seem to be incapable of recognizing the logical flaws in your own reasoning.

So other readers can see for themselves the sort of comment I trashed (keeping in mind that too many similar had already been addressed in some depth):

Re: “You may as well dismiss the existence of everyone in the ancient world.” No, there is plenty of evidence that people existed in the ancient world.