A document I have not posted about yet is Secret Mark [link to earlychristianwritings.com] or the Secret Gospel of Mark [link to Wikipedia]. (The most controversial aspect of the passage and the letter accompanying it is the possible hint of a homoerotic Jesus.) The briefest introduction to the fragment is at the Gnostic Society Library, and a more detailed discussion is available at Westar Institute. If the fragment is genuine, it would appear that our canonical version of the Gospel of Mark is a shortened version for “lower grade” converts and that there was once a more complete version for those to whom higher secret doctrines were permitted.

A fresh approach to the document was posted on the Biblical History & Criticism Forum by Ken Olson and with his permission I am sharing it here with Vridar readers. Enjoy!

Tinker Tailor Soldier Forger

or What George Smiley Taught Me About Secret Mark: Lessons From John Le Carre’s Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.

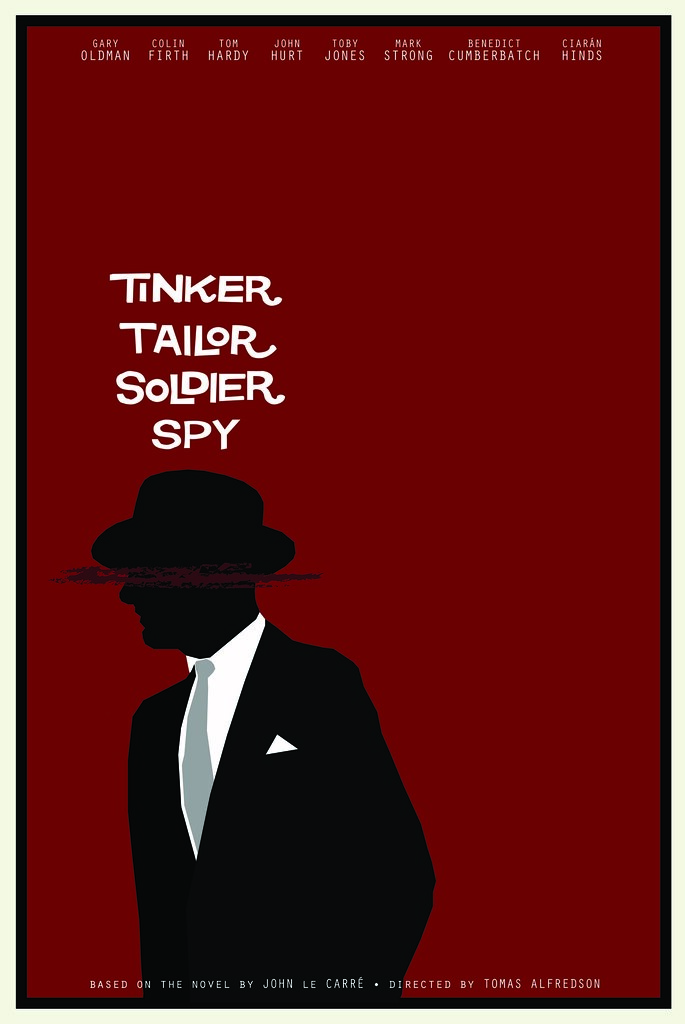

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is a classic 1974 espionage novel by John Le Carre (the pen name of David Cornwell), which has been made into a good movie starring Gary Oldman (2011) and an excellent miniseries starring Alec Guinness (1979). Cornwell is a former agent of the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI-6) himself and his novels are far more realistic (or, if you prefer, have more verisimilitude), than Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels, let alone the Bond movies. Anyway, if you haven’t read or watched it, you should.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy is a classic 1974 espionage novel by John Le Carre (the pen name of David Cornwell), which has been made into a good movie starring Gary Oldman (2011) and an excellent miniseries starring Alec Guinness (1979). Cornwell is a former agent of the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI-6) himself and his novels are far more realistic (or, if you prefer, have more verisimilitude), than Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels, let alone the Bond movies. Anyway, if you haven’t read or watched it, you should.

The plot was inspired by the historical Cambridge Five spy ring, which included a top level MI-6 agent who was a mole passing secrets to the Russians. In the novel, a forcibly retired former agent named George Smiley is brought in by a government minister to try to uncover who among the top level agents of the Service (who are given the code names Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, etc.) is a mole working for the Russians.

There a number of gems in the book.

In one place, Smiley is asked for his opinion on a file containing a Soviet internal review of their naval capabilities, which is something the Service has been after, and has now come into their hands from a mysterious source. Smiley comments (in the TV version):

Its topicality makes it suspect

In another place, Smiley muses on why it’s so difficult to convince his fellows that some of the intelligence they’ve been receiving from the same source is actually being fed to them by the Russians:

Have you ever bought a fake picture? … The more you pay for it, the less inclined you are to doubt it. Silly, but there we are.

In a long passage, Smiley is reading over a personnel file concerning two of the Service’s agents, Bill Haydon and Jim Prideaux. The file contains an old letter from Haydon to a man named Fanshawe (addressing him as “Fan,” which suggests they had a warm relationship), who was his tutor (i.e., the talent spotter from the Service who had recruited him), recommending that he also recruit his new friend Prideaux. In the course of praising Prideaux, Haydon says a few things that could perhaps be taken to suggest the two were more than just friends:

he’s only just noticed that there is a World Beyond the Touchline, and that world is me.

He’s my other half, between us we’d make one marvelous man … you know that feeling when you just have to go out and find someone new or the world will die on you?

he asks nothing better than to be in my company and that of my wicked, divine friends.

Nothing explicit, but as Smiley turns the pages in the file he finds:

The tutors of the two men aver (twenty years later) that it is inconceivable that the relationship between the two was ‘more than purely friendly’ …

Why does John Le Carre, the author, add the note from the two men’s tutors that it was *inconceivable* that their relationship was ‘more than purely friendly’ immediately after the text of Haydon’s letter about Prideaux? Was Le Carre concerned that his readers might take some of Haydon’s fulsome praise of Prideaux as suggesting there was a homosexual attraction between the two, and wished to allay that suspicion? If so, it backfires spectacularly.

Readers are much more likely to wonder why it was necessary for the tutors to report that the relationship between Haydon and Prideaux was definitely not homosexual in nature. The report gives the readers a context in which to understand the contents of the letter. If they had suspected there was something homoerotic in the contents of Haydon’s letter before, their suspicions are only going to be heightened by the denial in the report, and if they hadn’t picked that up from the contents of the letter, they probably will after seeing the appended note.

It seems more likely that Le Carre, a gifted writer, knew perfectly well what effect the appended note from the men’s tutors would have on his readers and included it for that reason. It’s a literary device. (Well, Okay, Le Carre has talked about how he conceived the homosexual relationship between Haydon and Prideaux in interviews, so that part is not really in dispute. What I’m discussing is the literary technique he used to reveal it to his readers).

Inception: How to Put an Idea in Someone’s Head

Continue reading “Tinker Tailor Soldier Forger (A Fresh Look at Secret Mark)”