Richard Carrier has posted his response to David Litwa’s chapter that professes to be addressing the Christ Myth theory:

Richard Carrier has posted his response to David Litwa’s chapter that professes to be addressing the Christ Myth theory:

I also posted on the same chapter by Litwa:

Carrier’s post comes with a much more lively and colourful style than mine.

Musings on biblical studies, politics, religion, ethics, human nature, tidbits from science

I’m sidestepping Fischer and Newall for a moment to focus on one instance of a fallacy that both of them seem to have overlooked. It as one type of an “appeal to authority”.

[M]ost people do not have a sufficient background in the subject to properly evaluate the evidence. Anti-Stratfordians [those questioning the authorship of Shakespeare’s plays] tend to be amateurs who have not read enough on Elizabethan theatre to see just how wildly implausible their ideas are. Let me give you an analogy. I can recognise the difference between a Yorkshire and Lancashire accent without very much trouble because I am English. I would never mistake an Irishman for a Scotsman. On the other hand, when I was living in New Jersey, I was frequently assumed to be Irish and had no idea that Californians sound different to Texans. Distinguishing accents isn’t something you tend to be taught. Rather you learn it by experience and by being immersed in a particular culture. It’s the same with history. If you have been studying a period for long enough, ideas like the anti-Stratfordians’ are as obviously incongruous as a baseball bat on a cricket pitch. (Hannam, xii)

The Latin label of that fallacy of appealing to authority is argumentum ad verecundiam. Verecundiam means shame or modesty; the idea being that an appeal to authority is an acknowledgement that the one making the argument lacks the expertise but modestly defers to another who is an expert. There is nothing modest about the above appeal, however. Yet it does demand modesty on the part of anyone who disagrees.

I found the following online explanation the most apt description where it is called Appeal to Confidence:

The arguer supports a position by appealing to himself as knowledgeable or trustworthy on the given subject, while at the same time declining to explain the actual reasons for a position. . . .

The argument appeals to confidence-building phrases, such as “trust me,” or “take it from me,” or makes an explicit claim to authority, such as “I know what I’m talking about.”

The historian who wrote that passage claiming that a historian “just knows” by being immersed in the field what is a valid argument and what is not is James Hannam (also author of God’s Philosophers). The difference between a valid and invalid idea cannot always be taught? That’s what he is saying there and it is perhaps relevant that he is not speaking of those who question whether Shakespeare wrote his plays but whether Jesus existed or not. The passage is from James Patrick Holding’s Shattering the Christ Myth. Hannam is the only professional historian contributing to that volume.

Hannam speaks of “experience” and “immersion in a particular culture”. That is indeed the critical factor. It is that sort of background that makes unquestioned assumptions so hard to identify and pull out for serious examination.

As for “cultural immersion” being a solid basis for identifying an anomalous argument, Hannam is clearly unaware of a growing number of biblical scholars (still a minority, of course) who do not consider the Jesus myth idea so “incongruous” as he suggests.

“Appeal to Confidence.” 2019. Bruce Thompson’s Fallacy Page. September 2019. https://www2.palomar.edu/users/bthompson/Appeal%20to%20Confidence.html.

Hannam, James. 2008. “A Historical Introduction to the Myth That Jesus Never Existed.” In Shattering the Christ Myth, edited by James Patrick Holding, xi–xvii. Xulon Press.

This is just a curiosity post in response to someone raising a query about the golden thigh of Pythagoras and wondering if there is any connection with the use of the word thigh as a euphemism for genitalia in the Bible.

To begin, here are the sources for the idea that Pythagoras had a “golden thigh”. It is difficult to interpret the word as anything other than a literal thigh. But we will see there is more to Greek mythical associations with the thigh in the next section.

They come from “the fragments” of what ancients recorded of their knowledge of what Aristotle wrote. They are all collated in a volume available at archive.org — pages 134 and 135.

APOLLON. Mirab. 6. These were succeeded by Pythagoras son of Mnesarchus, who first worked at mathematics and arithmetic, but later even indulged in miracle-mongering like that of Pherecydes. When a ship was coming into harbour at Metapontum laden with a cargo, and the bystanders were, on account of the cargo, praying for her safe arrival, Pythagoras intervened and said: ‘Very well, you will see the ship bearing a dead body.’ Again in Caulonia, according to Aristotle, he prophesied the advent of a she-bear; and Aristotle also, in addition to much other information about him, says that in Tuscany he killed a deadly biting serpent by biting it himself. He also says that Pythagoras foretold to the Pythagoreans the coming political strife; by reason of which he departed to Metapontum unobserved by anyone, and while he was crossing the river Cosas he, with others, heard the river say, with a voice beyond human strength, ‘Pythagoras, hail!’; at which those present were greatly alarmed. He once appeared both at Croton and at Metapontum on the same day and at the same hour. Once, while sitting in the theatre, he rose (according to Aristotle) and showed to those sitting there that one of his thighs was of gold. There are other surprising things told about him, but, not wishing to play the part of mere transcribers, we will bring our account of him to an end.

Further from the same source . . . .

AELIAN, V.H. 2. 26. Aristotle says that Pythagoras was called by the people of Croton the Hyperborean Apollo. The son of Nicomachus adds that Pythagoras was once seen by many people, on the same day and at the same hour, both at Metapontum and at Croton; and at Olympia, during the games, he got up in the theatre and showed that one of his thighs was golden. The same writer says that while crossing the Cosas he was hailed by the river, and that many people heard him so hailed.

Ibid. 4. 17. Pythagoras used to tell people that he was born of more than mortal seed; for on the same day and at the same hour he was seen (they say) at Metapontum and at Croton; and at Olympia he showed that one of his thighs was golden. He informed Myllias of Croton that he was Midas the Phrygian, the son of Gordius. He fondled the white eagle, which made no resistance. While crossing the river Cosas he was addressed by the river, which said ‘Hail, Pythagoras!’

DIOG. LAERT. 8. 1. 11 (9). He is said to have been very dignified in his bearing, and his disciples held that he was Apollo, and came from the men of the north. There is a story that once, when he was stripped, his thigh was seen to be golden; and there were many who said that the river Nessus had hailed him as he was crossing it.

IAMB. V.P. 28. 140-3. The Pythagoreans derive their confidence in their views from the fact that the first to express them was no ordinary man, but God. One of their traditions relates to the question ‘Who art thou, Pythagoras?’; they say he is the Hyperborean Apollo. This is supposed to be evidenced by two facts: when he got up during the games he showed a thigh of gold, and when he entertained Abaris the Hyperborean he stole from him the arrow by which he was guided. Abaris is said to have come from the Hyperboreans collecting money for the temple and prophesying pestilence ; he lived in the sacred shrines and was never seen to drink or eat anything . . . .

But there is more. There is something suggestive about the thigh in other myths.

One that comes to mind is the birth of the god Dionysus from the thigh of Zeus. Zeus had seduced and impregnated Semele but when Semele died before her time to give birth (Zeus’s jealous wife had tricked Zeus into causing Semele’s death by appearing before her in all his divine glory) Zeus snatched up the child and sewed him into his thigh until he was ready to be born. (Dionysus thus was known as the twice-born god.)

But why the thigh? We believe that we are dealing here with a literal translation of a West Semitic idiom which euphemistically designated begetting: “sprung from one’s thigh” (yōṣe’ yerēkó, inaccurately translated in English Bibles by “loins”) merely meant “begotten by one,” his child.

(Astour, 195. Note that the Greek myth of Dionysus was borrowed and adapted from Phygia in Asia Minor.)

In the literature of ancient Greek myths thigh wounds are often euphemisms for castration. So . . .

Classical scholars are generally aware of the trope that in literature from around the world thigh wounds are often euphemistic for castration, or at least for impotence. But classicists have not noted how thigh wounds frequently symbolize not only physical impotence but political or spiritual impotence, and how such wounds also represent a temporary or permanent loss of heroic status for the wounded individual as well as a crisis for the group of people represented by that individual. This association apparently has its roots in a belief, held by many cultures, that semen was produced in several places in the body, including in the marrow of the thigh bone, and the thighs’ proximity to the testicles resulted in a close association that was nearly an interchange between the thighs and the male genitalia. Consequently, any kind of wound to the thigh, whether a wrenching, piercing, crushing, or other injury or mutilation, could represent a blow to a man’s physical and spiritual virility. . . . .

(Felton, 47f)

Some ancient physiology and learning why ankle wounds so often proved fatal: Continue reading “Thighs: Pythagorean, Biblical and Other”

We hear over and over that Australian nationalism was forged in the crucible of war.

We hear over and over that Australian nationalism was forged in the crucible of war.

The Australian War Memorial preaches this belief with its Forging the Nation exhibition.

The renowned war historian C.E.W. Bean made the message clear in his history of Australia in World War 1:

And then, during four years in which nearly the whole world was tested, the people in Australia looked on from afar [and] saw their own men flash across the world’s consciousness like a shooting star. Australians watched the name of their country rise high in the esteem of the world’s oldest and greatest nations. Every Australian bears that name proudly abroad today; and by the daily doings, great and small, which these pages have narrated, the Australian nation came to know itself…

We are repeatedly reminded of headlines like the following:

But it’s not true. It is a myth. Australian nationalism was alive and flourishing in the years preceding and following Federation in 1901. An Australian identity — the one that is propagandized today with its stress on mateship and egalitarianism — was there in the cultural, social and political life of Australians before 1914.

I wish I could locate the source of the words now but I recently heard a woman being interviewed on Late Night Live, I think it was, remarking that the Great War broke Australia. It changed us as a nation. We lost our confidence not just from the immediate trauma of the four years of battle but from the many traumas of trying to rebuild lives in the years following.

With Federation in 1901 the big question was what sort of nation Australians wanted to build:

‘’A new demesne for Mammon to infest?

Or lurks millenial Eden ’neath your face?”Was the continent to see repeated the evils of other civilizations, the ravages of war, the co-existence of great wealth and abysmal poverty, the rigid class structure of privilege, or was it, on the other hand, free of the taint of older societies, to produce a civilization in which the individual dignity of man had full respect?

(Greenwood, 199. The poetry is from the Bernard O’Dowd’s prize-winning poem challenging the emerging nation in 1900 to ask what sort of society it would make of itself.)

The mateship was there long before Gallipoli as anyone who has read Henry Lawson’s poetry should know.

Bitten deep into the consciousness of the men and women who espoused the Labour cause was a belief in the importance of solidarity, of sticking together, of being able to rely on one’s mate. (200)

And it wasn’t confined to the labouring class, either:

While the more advanced liberals had in common with the leaders of political Labour a belief in experimentation, a sense of Australianism, a recognition of the necessity for remedying social injustice by State action, and, in the larger view, an optimistic acceptance of the social democratic doctrine of progress, all this sprang from genuine conviction, for the faith to which they held and by which they acted was their own and not merely a pale reflection of Labour doctrine. (203)

Australian values (good and bad) were being self-consciously “defined and firmly established” from at least as early as 1901. There was a confidence we would scarcely recognize today, a confidence in the ability to transform and make a more just society, one free of poverty and inequality and exploitation (205).

There was a tone of self-confidence about the pre-1914 nationalist creed. The world was young, and despite the turmoil and depression of the nineties there was an idyllic and anticipatory assumption of future triumphs. Power and creative vigour, the impulse to assert the dignity of the ordinary man through a new Australian social order and the exhilaration of building towards an independent and native cultural tradition all belong to the movement. (207)

Geographic realities meant that the nation had to come together to work through a centralizing power. (See Australia and the United States – Interesting Comparisons for a comment on Australia’s attitude towards central government.) There was also the labour movement’s felt need to take control of the power that had formerly been used to oppress them into accepting unsafe and intolerable conditions. But the core values were shared by both sides of politics:

Humanitarian liberalism, whether of the Deakin [i.e. Liberal] or Fisher [i.e. Labor] variety, was in the ascendant until the war of 1914. Liberal and Labour governnicnts testified in action to their belief in the efficacy of State enterprise. Their social and economic principles were worked out in the field of public policy, and by experimentation they endeavoured to forge new instruments of social and economic justice . . . . Social aims, however, touched almost all legislation . . . . (210-11)

So what were some of the achievements of that “social experiment” of the pre-War years? What particulars are worthy of being remembered and celebrated and embraced as proud achievements of a nation? Here are a few: Continue reading “What Could Australia Be without War?”

A related informal fallacy is post hoc, ergo propter hoc (“after this, therefore because of this”) which holds that if one event follows another then the former must have caused the latter. (Similarly, cum hoc, ergo propter hoc involves the assertion “with this, therefore because of it.”) That Chamberlain’s government pursued a form of appeasement and then war followed does not imply that one necessitated the other. As before, the error lies in assuming that no other causes were operating.

(Newall, 265)

One form of the fallacy is the “follow the money trail” or the “who benefits” (que bono) principle in forming a historical argument.

Several historians of post Soviet Russia have fallen into this error. Their argument is that market reforms following the collapse of the Communist government have benefitted a handful of elite oligarchs and that by a form of post hoc

It is tempting to argue post hoc ergo propter hoc: that those who benefitted from the market reforms were not only its main defenders, but even its principal instigators. So, market reform is seen to be the result of a deliberate policy by far-sighted communist bureaucrats to convert their collective political authority into private negotiable assets, an interpretation favored by both the Left (Kotz andWeir, 1997) and the Right (Satter, 2004; Hedlund, 2000).

But a more careful exploration of the actual evidence does not support that tempting theory:

Many of them were young and far removed from the core decision-making process in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Their political influence came after they became wealthy, not before.

(Rutland, 339)

We have seen several comments on this blog making the same type of argument in relation to Christian origins. The example I list is not a dig at any person but simply an attempt to draw attention to what I see as a flaw in the argument that has been proposed here. Take this post as an invitation to strengthen the argument by removing their weaknesses:

Another one posted in the comments here argues for a 9/11 conspiracy the same way:

Again, that’s another instance of the same fallacious reasoning.

It is a favourite of politicians:

Another example:

In fact, Spain’s empire continued without any losses for decades afterwards. It has also been shown that the loss of the Armada was followed by a serious development of the Spanish navy. There is little evidence that Spain and her place in the world suffered any long term damage as a result of the failure of 1588.

Fischer gives us another instance:

An example is provided by a female passenger on board the Italian liner Andrea Doria. On the fatal night of Doria‘s collision with the Swedish ship Gripsholm, off Nantucket in 1956, the lady retired to her cabin and flicked a light switch. Suddenly there was a great crash, and grinding metal, and passengers and crew ran screaming through the passageways. The lady burst from her cabin and explained to the first person in sight that she must have set the ship’s emergency brake!

(Fischer, 166)

To establish a hypothesis that event B was the result of the preceding event A the historical inquirer needs to point to evidence of a causal link. Simply declaring that “it is obvious” because one followed the other is not sufficient.

One frequently comes across this particular fallacy. Feel free to add more.

Fischer, David Hackett. 1970. Historians’ Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought. New York: Harper.

Newall, Paul. 2009. “Logical Fallacies of Historians.” A Companion to the Philosophy of History and Historiography, edited by Aviezer Tucker and Mary Kane, Wiley-Blackwell.

Rutland, Peter. 2013. “Neoliberalism and the Russian Transition.” Review of International Political Economy 20 (2): 332–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692290.2012.727844.

I wanted to understand the mind of the Trump supporter a little better so I read The MAGA Doctrine by Charlie Kirk (Donald Trump highly recommended it in a Tweet). In the Preface Kirk tells us that the book is a kind of manifesto of what Trump supporters think he is all about:

I wanted to understand the mind of the Trump supporter a little better so I read The MAGA Doctrine by Charlie Kirk (Donald Trump highly recommended it in a Tweet). In the Preface Kirk tells us that the book is a kind of manifesto of what Trump supporters think he is all about:

I’ve seen President Trump speak in front of high school students, my fellow young conservative activists eager to hear him — and afterward, I often hear students ask me, is there a key book or manifesto I can study to really understand the philosophy behind this burgeoning movement? . . . . Now there is. I would not presume to speak for the president, but I will try as best I can to explain the old ideas underlying the fresh thinking he brings to a country that desperately needs it.

Before I finished it an eerie recollection of another book kept intruding into my mind, one that I read many years ago as a historical document behind another disruptive right-wing movement. That was Mein Kampf by Adolf Hitler. No, of course neither Kirk nor Trump are Nazis or advocating the extermination of Jews and war to find living space for Germans. As someone else has pointed out, Trump is something of the polar opposite of a Nazi in that he enables the Business world to rule government (Nazis controlled every aspect of life including Business). So what was it that brought Mein Kampf to my mind?

Mein Kampf blamed Germany’s woes on the betrayal of evil-minded or simply immoral Jews (that’s my recollection, at least). MAGA Doctrine had a parallel theme. All USA’s woes (and some of them imaginary) can be blamed on a betrayal of traitorous, immoral “liberals”.

Just as Mein Kampf, as I recall it, failed to understand clearly the way German society worked by replacing clear-headed analysis with imagined conspiracies and betrayals and selfish anti-German motives of Jews and those who let Jews have their way, so Kirk shows no evidence of a clear-headed, informed awareness of either US or world history. Everything, all history and current affairs, are seen through the perspective of a “betrayal of liberals”.

Simply replace Jews with “liberals” and we have a book with a very similar theme.

Liberals appear by definition to be unpatriotic, hypocritical, stupid, sinister. And they lie with their “corrupt media”. It is impossible to reconcile the way Kirk portrays their policies with reality as anyone who has seriously studied them and their philosophy would know.

Ignorance pervades the book. Karl Marx — and by extension, all “socialists”, and by extension, many “liberals” — is even said to be opposed to any form of fair exchange of goods.

There can be no honest debate or discussion with a mind that is convinced from the outset that the opponent is a hostile subversive who wants to undermine all that you believe is good.

There can only by mud-slinging and misrepresentation from the MAGA side.

. . .

Then I noticed something else on the web, this time by someone accusing others with alternative views of Jesus of being hell-bent on attacking and destroying Christianity. I guess it’s the same with some biblical scholars, too. Some of them find it necessary to personally attack those (especially outsiders) who explore different perspectives on Christian origins so that the mainstream assumptions are called into question. The idea that others with radically different perspectives (and questions) might be seeking to be as intellectually honest as they can is something they seem not to be able to accept. (Yes, I’m thinking primarily of those who suggest it is legitimate to at least question the historicity fo Jesus just as some scholars have questioned the historicity of “biblical Israel”.) Such critics are assumed from the outset to be sinister, motivated by destructive and harmful wishes against the most precious beliefs humanity possesses.

And so the world turns.

Continuing the series on Nanine Charbonnel’s Jésus-Christ, sublime figure de paper . . . .

Continuing the series on Nanine Charbonnel’s Jésus-Christ, sublime figure de paper . . . .

–o–

After this post I will pause from addressing NC’s book for a little while because I want to get a firm grasp of the next section before posting, and I think it is a very critical section, one that addresses the formation of the figure of Jesus in the gospels.

Here we continue the theme of suggesting what collective groups different individual persons in the gospels represent. The key takeaway is that there are reasons to think that certain names stand for larger entities, e.g. John the Baptist represents the Prophets of the “Old Testament” pointing to Jesus, the twelve disciples represent the foundation of the “new Israel” or Church, and so forth. In this post we have a look at the virgin mother of Jesus.

On “Twelve disciples” as the foundation of a “new Israel”: I have tended to think that the idea of the Twelve Disciples as a foundation of the Church was a second-century attempt to rebut Marcionism (i.e., the belief that Paul alone was the one true apostolic founder of the church). If so, the Gospel of Mark which arguably depicts Peter and the Twelve as failures (see Ted Weeden), was in some sympathy with Marcionism, but the later gospels with their positive spin on the Twelve stand in opposition to Marcionism; if so, they would have been authored closer to the mid-second century. Perhaps even the Gospel of Mark was written as an attempt to denounce attempts to establish a certain “orthodoxy” on the myth of The Twelve as opposed to Paul.

–o–

Other Vridar posts on the Cana miracle are by Tim Widowfield:

Again we notice evidence of symbolism in a gospel story. We have a wedding narrative consisting of inversions of passages in the Jewish Scriptures. Other figurative language in the gospels leads us to see this wedding as a representation of an end-time event, a successful marriage to supplant the failed marriage of “old Israel” with Yahweh.

The following table blends parts of what I read in both Charbonnel and Mergui‘s books:

| Jn 2:1 | On the third day, | Hosea 6:2 “After two days he will revive us; on the third day he will restore us, that we may live in his presence. (i.e. a New Creation) |

| a wedding took place at Cana in Galilee | The Wedding = the covenant of Yahweh with his people Israel;

Galilee = the land of gentiles. (Isaiah 9:1) Cana = from late Hebrew qanah meaning to acquire, to gain, to possess (c.f. Cain) The scene represents the end time wedding of the enlarged Israel that includes gentiles. |

|

| Jesus’ mother was there | The mother is also the people, the bride (Isaiah 22) | |

| 2:2 | and Jesus [= YHWH who Saves] and his disciples had also been invited to the wedding. | The messiah is the husband of his people (Jer. 31:3) |

| 2:3 | the wine was gone,

“They have no more wine.” |

The wine is the Word or Law of Yahweh (Prov. 9:5; compare Ps. 73:10 where “waters” = word of Yahweh).

The old wine thus suggests the first (Mosaic) Law. The words of the mother of Jesus, or the old Israel, contains a recollection of the rebellion of Israel with its complaining to God of what they lacked, or rebellion against the law. This may explain Jesus’ distant response. |

| 2:4 | “Woman” | = Eve (Genesis 2:23) |

| 2:5 | His mother said to the servants, “Do whatever he tells you.” | = the text of Genesis 41:55 — “Go to Joseph and do what he tells you.” (Jesus is the new Joseph who has come to feed his people.)

Obedience leads to a new wine, one that is much better — the new Law that replaces the old. |

| 2:6 | Nearby stood six stone water jars | Six is the number of incompleteness: we are on the cusp of the last days.

The purification jars are filled with water (for purification of the Jews) but wine replaces mere water of purification |

| 2:8 | Then he told them, “Now draw some out” | The messiah brings new wine: Joel 3:18; Isaiah 25:6; Hosea 14:7 |

Keep in mind that NC is not merely saying that gospel characters are symbolic. The point is much richer than that. The figures and actions are constructed in dialogue with (and with the use of) extracts from the Hebrew Bible. This is their midrashic nature.

NC shares an idea from (who has set out his own case for the Gospels of Luke and Matthew being a form of Jewish midrash on the Old Testament) in which the gospels have engaged with a rabbinical view of their time that Moses was born of a virgin. Again, we find the clues in the later writings of the Talmud and suspect the claim that they represented very early traditions may have some factual basis.

Exodus 2:1-2 (NKJV)

And a man of the house of Levi went and took as wife a daughter of Levi. So the woman conceived and bore a son. And when she saw that he was a beautiful child, she hid him three months.

In the Babylonian Talmud’s Sotah 12a we read that Amram and Jochebad, the parents-to-be of Moses, divorced when learning of Pharaoh’s decree that all male children of Hebrew marriages would be killed. Their daughter Miriam, however, advised Amram that he had been wrong to put her away and to take her back and remarry her.

At this time Jochebad was 130 years old. In several ways Jochebad was seen to represent the entire body of Israel. Though conceived outside Egypt she was born to Levi in Egypt, so her life had spanned the entire time of Israel in Egypt, and her actions were reported to and followed by all of Israel. Just as Egypt, a representative of the pagan nations, carried within its own womb the hope of her salvation, that is Israel, so Jochebad, bore in her womb the future liberator of Israel. The fact that she was taken back by her husband who had decided not to have any more relations with her is interpreted by the Jewish tradition as the symbolization of the renewal of the community.

Now when Jochebad was restored to Amram God performed a remarkable miracle. He changed her back to a young maiden, a virgin even. Continue reading “Symbolic Characters #3: Mary, Personification of the Jewish People, “Re-Virgined””

I know, I’ve addressed this question before, but I’ve just come across evidence from a new source so here we go again. It’s a rabbinic source but don’t be too quick to judge that it is late and therefore useless. Can anyone seriously imagine Jewish rabbis borrowing the following interpretations from Christians?

I know, I’ve addressed this question before, but I’ve just come across evidence from a new source so here we go again. It’s a rabbinic source but don’t be too quick to judge that it is late and therefore useless. Can anyone seriously imagine Jewish rabbis borrowing the following interpretations from Christians?

We read a discussion among rabbis of the following rabbinical midrash on the Book of Ruth:

“And Boaz said unto her at meal-time: ‘Come hither, and eat of the bread, and dip your morsel in the vinegar.’ And she sat beside the reapers; and they reached her parched corn, and she did eat and was satisfied, and left thereof (Ruth 2:14)”.

Several interpretations are offered and then we come to the fifth:

The fifth explanation for “come here” is the King Messiah. “Come here”: that is draw near to kingship. “And eat from the bread”: that is the bread of kingship. “And dip your morsel in the vinegar“: this is his chastisements, as it is said: “But he was wounded because of our transgressions (Isaiah 53:5)“.

Did the Rabbis learn and embrace that interpretation from their Christian neighbours?

As we read further on we find it even more difficult to accept a Christian influence here. The rabbinic interpreters discuss how long the kingship will be removed from the Messiah and no-one hits on a three-day eclipse:

“And she sat beside the reapers”: that is the kingship was taken from him for a time, as it is said “I have gathered all the nations against Jerusalem to wage war and the city will be taken (Zechariah 14:2)”.

“And they reached her parched corn”: that is his kingship was renewed, as it is said “and he shall smite the land with the rod of his mouth (Isaiah 11:4)”.

Rabbi Berechya said in the name of Rabbi Levi: “like the first redeemer so is the second redeemer. How did the first redeemer reveal himself and then returned and was hidden from them? How long was he hidden? . . . .

One rabbi calculates from Daniel 12:11-12 that the Davidic Messiah will be removed from his kingdom for 45 days. Another suggested a full three months (from a meeting of Moses and Aaron with the elders of Israel), another six months (from the time David fled Absalom). Another rabbi even suggested it spoke of Solomon who left his throne for a while to mingle unrecognized with the hoi polloi and that one woman even beat him for being a pretentious upstart when he tried to explain he indeed was Solomon.

We cannot prove that any of the ideas expressed in the Ruth Rabbah originated before the destruction of the Temple. It is difficult, though, to imagine such ideas taking hold among rabbis in a context of tortured relationships with Christianity. Further, it is not difficult to imagine the motifs we find in the gospels arising from an environment in which Biblical passages were explored in the sorts of ways we see here.

.

(Thanks to Nanine Charbonnel and Maurice Mergui for prompting me to revisit rabbinic literature and see how it deals with Messianic ideas.)

“Ruth Rabbah.” Accessed April 21, 2020. https://www.sefaria.org/Ruth_Rabbah. See especially chapter 5.

Continuing the series on Nanine Charbonnel’s Jésus-Christ, sublime figure de paper . . . .

Continuing the series on Nanine Charbonnel’s Jésus-Christ, sublime figure de paper . . . .

–o–

Maybe I’m just naturally resistant to new ideas but I found myself having some difficulty with Nanine Charbonnel’s [NC] opening stage of her discussion about John the Baptist. (Recall we have been looking at plausibility of gospel figures being personifications of certain groups, with Jesus himself symbolizing a new Israel.) NC begins with an extract from Maximus of Turin’s interpretation: by cross-referencing to Paul’s statements that the “head of a man is Christ” (1 Cor. 11:3) Maximus concluded that the decapitation of John the Baptist represented Christ being cut off from the adherents to the Law, the Jews. Without the head they were a lifeless corpse.

We may not like that interpretation but at least Maximus recognized something symbolic about John the Baptist. As NC reminds us, he was the one who greets the messiah from his mother’s womb (Luke 1:41), the one who asks questions designed to recognize Jesus, the one who acts out Elijah’s confrontation with the lawless Jezebel and king Ahab. Even if we accept the entry about John the Baptist in Josephus as genuine and acknowledge that there was a historical “John the Baptist”, this person is depicted in symbolic roles in the gospels.

NC has more to say but permit me to give my own view, or perhaps a mix of my own with NC’s. John the Baptist is presented initially in the physical image of the arch-prophet, Elijah, and is calling upon all Israel to repent and prepare for the messiah. They all come out into the wilderness to do so. In Luke’s gospel when different groups (soldiers, tax collectors and others) ask John what they should do John replies with the fundamental spiritual intent of the law in each case: be merciful. Surely this is all symbolic of the Law and Prophets being the articles of the covenant made between Israel and God in the wilderness, and just as the early Christians found Jesus predicted in the prophets so John, the final prophet, points them to Jesus the messiah. Later we find the same prophet asking Jesus if he is the one, with Jesus replying with signs as recorded in the Prophets to assure him. John, meanwhile (as NC herself notes as significant), is martyred just as many other prophets before him, and just as Jesus himself will be. The tale is surely told as symbolism and the character John as a literary personification. Jesus emerges from the Prophets. It is the Prophets who all point towards Jesus Christ.

So when John says he is not worthy to baptize Jesus, he is saying that Jesus is greater than the Law and Prophets. Jesus, however, replies that he has come to submit to the Law and Prophets. His baptism represents the emerging in his full spiritual reality the new Israel, the one prophesied in the prophets. This is not the baptism described in Josephus. It is a baptism of repentance, of preparation for the Christ.

The absence of biographical or other historical information is telling. We only have details that call out for symbolic interpretation. The reason each evangelist can modify the narrative is not because they were working with historical data but entirely in their own imaginative interpretation of the way the Prophets pointed readers to Christ.

The famous Gregory who became the Pope in the sixth/seventh century identified a possible symbolic meaning of the Gospel of John’s account of John and Peter running to the empty tomb. Quoted by NC, Gregory sought a meaning in John arriving first at the tomb but not entering, with Peter coming later yet being the first to enter. John was interpreted as the Synagogue, the Jews, who had “come first” to Christ, but failed to “enter”. Peter, representing the gentiles, arrived later but was the first to believe. [See Gregory the Great Homily 22 on the Gospels; see also comments below for further discussion]

The two were running together, but the other disciple outran Peter and reached the tomb first. He bent down to look in and saw the linen wrappings lying there, but he did not go in. Then Simon Peter came, following him, and went into the tomb. He saw the linen wrappings lying there, and the cloth that had been on Jesus’ head, not lying with the linen wrappings but rolled up in a place by itself. Then the other disciple, who reached the tomb first, also went in, and he saw and believed . . . (John 20:4-8)

Interesting possibility. But if the “beloved disciple” is rather meant to be an unfalsifiable witness (and he, not Peter, is said to be the one who believed), it is hard to identify the same with the “Jews of the synagogue”. On the other hand, given what we know of Peter as the apostle to the gentiles, the one who stands between Jews and gentiles (hence his “double-minded” reputation?) something along the lines of Gregory’s interpretation does have some appeal.

Other points to consider, as per NC: John (meaning God is gracious) does have a sound similarity to Jonah, another representative of Jews in the old story. (Then we also have Peter being identified in the Gospels of Matthew and John with the son of Jonah.) NC promises to return to Peter in the last chapter. I will be patient.

Again, we have details that are not typically found in biographies. Recall the same point (especially with respect to the Gospel of John) in How the Gospels Became History. Such details appear pointless in themselves; they scream out for symbolic interpretation — and many ministers and preachers have understood this point well enough to prepare many sermons drawing out various meanings for their congregations.

This one is easier. The twelve patriarchs in Genesis are treated as symbolic representatives of the tribes that bore their names. I think many of us have seen in the Twelve Disciples a new founding group of the “new Israel”.

NC sees three principles underlying any interpretation of the Twelve. Continue reading “The Symbolic Characters in the Gospels #2: John the Baptist and the Twelve Disciples”

A false dilemma is seen whenever only two possible options are given when there exist others. (This fallacy is also known as a false dichotomy). For example, a person might insist, “you’re either with me or against me” and hence force the listener to join forces or else be taken as an enemy. In general, we have the following:

P1: Either A or B;

P2: Not A;

C: Therefore, B.

The argument seems valid but a premise is missing; namely, something like “P3: No other options other than A and B exist.” It is often used for rhetorical effect; after all, if only two choices are available and one is unpalatable then we are forced to choose the other, even if we might otherwise have reservations.

(Newall, 264)

Some historians have fallen into this fallacious reasoning when addressing Neville Chamberlain’s responses to Hitler. Essentially the argument has been:

P1: Chamberlain had the option to either [A] stand up to Hitler and prevent war or [B] appease him and lead to further demands and world war.

P2: Chamberlain did not [A] stand up to Hitler and prevent war.

C: Therefore, [B] Chamberlain is to be blamed for making the cowardly choices that led to war.

What is missing are other “dilemmas” facing Chamberlain:

or C: Chamberlain believed Russia was a serious threat and believed Hitler would invade east, not west.

or D: Chamberlain feared Japan and Italy would take advantage of Britain being tied down with Germany to overrun British interests in Asia and the Mediterranean.

or E: Chamberlain knew Britain would not tolerate another war given their fresh memories of the horrors of the last one.

As summed up by Paul Newall: Continue reading “Logical Fallacies of Historians: the False Dilemma (Dichotomy)”

The fallacy of the circular proof is a species of a question-begging, which consists in assuming what is to be proved. . . . [I]t is exceedingly common in empirical scholarship. (Fischer, 49)

Begging the question (or petitio principii) occurs when the conclusion of an argument is used to demonstrate it, thereby achieving a circular proof. (Newall, 264)

Fischer offers a silly example to illustrate.

A researcher asks, “Do gentlemen prefer blondes?” He discovers that Smith, Jones, and James prefer blondes, and tacitly assumes that Smith, Jones, and James are therefore gentlemen. He concludes that three gentlemen out of three prefer blondes, and that the question is empirically established, with a perfect correlation. His argument runs through the following stages :

Inquiry : Do gentlemen prefer blondes?

Research : Smith, Jones, and James prefer blondes.

(Tacit Assumption) : Smith, Jones, and James are gentlemen.

Conclusion: Therefore, gentlemen prefer blondes.

Here are some other examples I’ve considered. Let me know if I have made mistakes or if you have others to add.

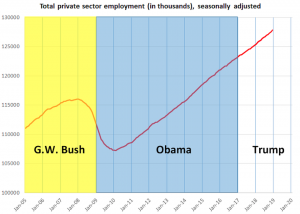

Inquiry: Has Trump been a good manager of the US economy?

Research: The GDP has increased under Trump’s presidency.

(Tacit Assumptions): Trump’s policies have been responsible for its growth and there are no negatives in the economy that outweigh the positive figures.

Conclusion: Therefore, Trump has been a good manager of the US economy.

– – – o – – –

Inquiry: Should Trump encourage people to try hydroxychloroquine as a cure for COVID-19?

Research: Trump and others say they have heard that many people have tried it and been cured of COVID-19.

(Tacit Assumption): The stories one has heard are all genuine and hydroxychloroquine was responsible for the cures and there have been no negative experiences with hydroxychloroquine.

Conclusion: Therefore, Trump should encourage people to try hydroxychloroquine as a cure for COVID-19.

– – – o – – –

Inquiry: Is the lockdown response an overreaction to the COVID-19 threat?

Research: I and other people I know are sensible and will keep social distancing advice without a lockdown.

(Tacit Assumption): the lockdown is an overreaction because everyone is like me and we can contain the COVID-19 spread without a lockdown

Conclusion: Therefore, the lockdown is an overreaction.

– – – o – – –

Inquiry: Is it a historical fact that Judas betrayed Jesus?

Research: It is unthinkable that the early church would make up a story of one of the inner Twelve betraying Jesus.

(Tacit Assumption): There was a historical Jesus with a historical Twelve disciples whom he trusted and the early church was dedicated to recording the historical facts.

Conclusion: Therefore it is a historically reliable tradition that Judas betrayed Jesus.

– – – o – – –

Inquiry: Did Jesus exist?

Research: No Jew would have made up a story about a crucified itinerant preacher being the Davidic messiah.

(Tacit Assumption): Jesus was historically an itinerant preacher who was crucified yet still believed by his followers to be the Davidic messiah.

Conclusion: Jesus existed. Continue reading “Logical Fallacies of Historians: Begging the Question”

A little rant:

No-one with “every single thing that could be wrong with a human being” could just walk in and become President of the United States without a little help from somewhere. So here we are, people going crazy with frustration as Trump does and says more and more wrong things. The “wrong things” are why his base loves him, of course. It’s a serious situation.

The real fault surely, as we all must know, is that

a. the Republicans know that supporting Trump is their only chance of protecting the economic and class interests of those they represent;

b. the establishment Democrats represent the other wing of the same economic and class elites as demonstrated by their nominations for Hilary Clinton and now Joe Biden to represent them.

The Coronavirus represents another opportunity for the corporations to entrench their power and wealth at the expense of the rest of the nation. As long as everyone is focused on the idiot showman and all of his nonsense they can get away with it largely unnoticed.

Meanwhile, the showman has accelerated a total breakdown in any ability of his supporters and opponents to actually talk and debate with each other. All criticism has been branded “fake news” of persons with some sort of mental syndrome. If one side attempts to focus on the facts of a record of behaviour the other side focuses on a selection of words and facts that portray an “alternative reality”. There is no common ground in the “conversation”.

A showman and an audience divided into two competing “realities”.

Meanwhile, untouched, the real powers who benefit from this whole scenario.

Elections are bought. The debates focus on the criminal clown and people rage within the echo chambers of different “realities”. Even if one reality is indeed “the” reality, the focus is still on the showman.

Somehow the focus needs to be redirected against those who buy the elections, that is against those who are benefiting from the political system that represents the corporate capitalist elites, against those politicians who are benefiting from all the attention, both supportive and critical, being on Trump.

The corporate capitalist system makes a mockery of what is called a “democracy” and is driving us all to any number of disasters.

End of my little rant.

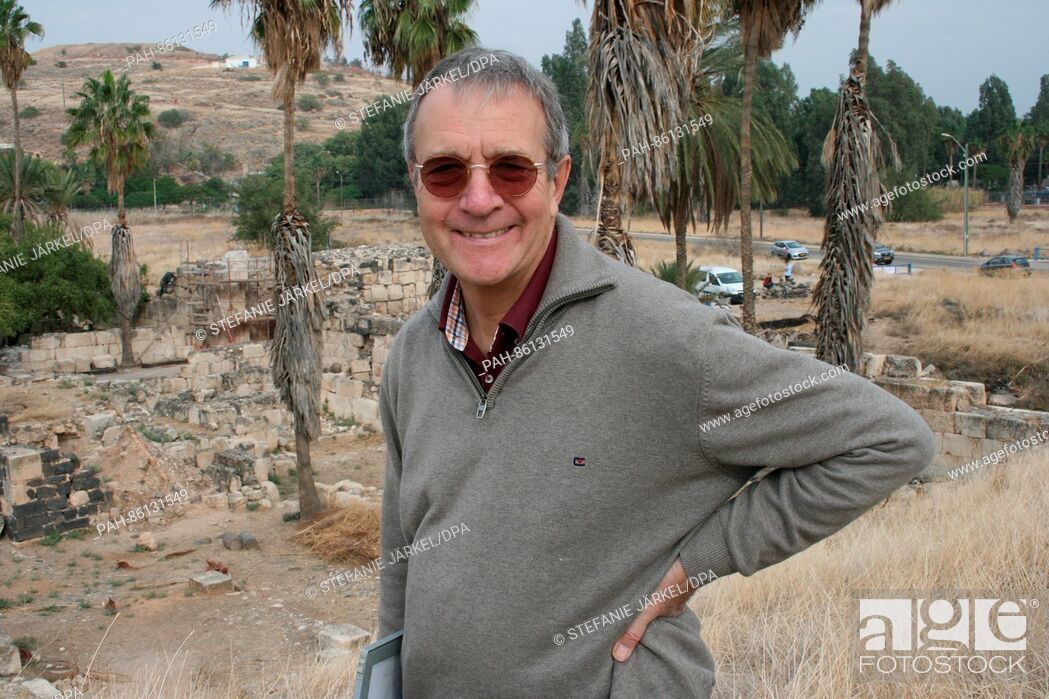

This post is an important and necessary follow up to my previous one about the falsehoods of O’Neill’s attacks on Salm’s work. Any readers with a serious interest in the dating of Nazareth and the seriousness of René Salm’s study of the archaeological record should be aware of the evidence that demonstrates how carelessly false Tim O’Neill’s public statements about his work really are.

Contrary to O’Neill’s assertions Salm did not mistranslate [my previous post demonstrated this by showing the locations of sites Kuhnen listed] or misinterpret Kuhnen as Kuhnen himself affirms in the following email exchange between Salm and Kuhnen and that I copy here with permission.

This first extract Kuhnen wrote initially to a third party but then copied to Salm himself. Bracketed clarifications are by Salm and the bolded highlighting is by me:

In my answer to Mr. Salm’s interesting question I referred to my Ph.D. thesis of 1982, published 1989 under the title “Studien zur Chronologie und Siedlungsarchäologie des Karmel (Israel) zwischen Hellenismus und Spätantike. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients B 72 . Wiesbaden 1989. On pages 49 – 72 of this book you’ll find a chronological analysis of Hellenistic – Roman tombs excavated up to then in Palestine. My chronology is based primarily on internal evidence, i. e. the combination of finds, a method common in European prehistory, but up to now not yet introduced in Palestinian archaeology. My “comparing [comparison—RS] table of datable tombs” (Kombinationstabelle der Funde aus Gräbern”. Beilage 3) clearly proves that all kokim tombs of my “phase I”* (2nd [cent. BCE]- early 1st century AD) are concentrated in the Judean hills around Jerusalem. The earliest kokim tombs of Galilee appear in my “phase II”, starting around the middle of the 1st century AD. Therefore, from the evidence published up to the 1990s, Mr. Salm is right that there is no clear evidence of tombs of the period of Jesus in Nazareth.

… I definitely share your scepticism about the historicity of the New Testament. Last year I held a seminar and an excursion at the Institute of Biblical Archaeology of Mainz University on Holy places on the shore of the Lake of Galilee, which showed clearly that the localization of New Testament sites in Galilee is the work of Byzantine historiographers and not of the writers of the New Testament.* “Kombinationstabelle der Funde aus Gräbern” is the heading of Appendix 3 (“Beilage 3”) of Kuhnen’s PhD thesis. The heading literally means “Combination table of finds from tombs.” That’s of course quite different from Kuhnen’s translation. The word “Kombination” in German has inferences that the English “combination” lacks, including “comparison” (hence my bracketed clarification). The German “Tabelle” variously can mean many things: “table, list, chart, index, schedule, synopsis, summary” (from my large Cassell’s English & German dictionary). I ILL’ed Kuhnen’s thesis years ago and don’t have it at hand, but if … memory serves, the appendix in question is in the form of a list. So, I would translate the entire phrase as “Comparison list of finds from tombs”, or “Master list of finds from tombs”, or even “Master summary of finds from tombs.” Of course, we’re not talking about Nazareth finds here, but those in the vicinity of Mt. Carmel in Lower Galilee, about 30 km WNW of Nazareth. — RS.So , from an archaeological point of view, Salm’s arguments about a completely Judean “theatre” of NT history cannot be disregarded, but it seems to me that discussion will go on for a long time. [Jan . 4, 2010]

Here are a couple of further snippets from Kuhnen’s emails to Salm. They demonstrate that there has been no daylight (“misunderstanding”) between Kuhnen and Salm on tomb dating. Kuhnen even states that he considers Salm’s study sufficiently worthy to be included in his curriculum. (Unfortunately not every email has the date stamp preserved.) In the posts directly to Salm himself Kuhnen wrote in German but Salm has added translations:

– Kuhnen writes: “Hinsichtlich der Datierung der bekannten Gräber haben Sie sicher recht.” (“Regarding the dating of the known tombs [in Nazareth] you are certainly correct.” (Dated May 15, 2009)

– “Ihre Überlegungen sind sehr anregend, besonders Ihre Hauptthese, dass die Evangelien im wesentlichen die Realität nach dem Jahr 70 n. Chr. beschreiben. Auch Ihrer Einschätzung von Bagatti stimme ich zu. Er und einige andere seiner Kollegen (de Vaux, Humbert) sind meines Erachtens typische Vertreter einer kirchlichen Archäologie, die in der Archäologie das bestätigt sieht, was sie schon vorher wusste.” (“Your reflections are very exciting, particularly your main thesis that the gospels essentially describe the post-70 CE reality. I also agree with your estimation of Bagatti. He and some of his other colleagues (de Vaux, Humbert) are, in my opinion, typical apologists for an ecclesiastical archeology that simply confirms what it already knows.”

– “Insgesamt finde ich, wie gesagt , Ihre überlegungen sehr interessant, und habe darüber auch schon den Studenten in meinem derzeitigen Seminar an der Uni Mainz berichtet. Im nächsten Semester möchte ich an der Uni Mainz ein kritisches Seminar zum Thema “Archäologie und Neues Testament” anbieten. Dabei werden wir sicher auch Ihr Buch behandeln.” (Translation: “In all, I find your reflections very interesting, as mentioned above. I have already communicated your views to students in my current Seminar at the Univ. of Mainz. Next summer I would like to offer a critical seminar on the Archaeology of the New Testament. In it we will certainly discuss your book.” (Second half of May 2009.)

I said in my previous post that contrary to the impression created by O’Neill Salm has engaged with Kuhnen’s work in considerable depth and most certainly was not “quote mining” a single sentence. Here is a list of all of Kuhnen’s works consulted by Salm from the bibliography of his second book, NazarethGate:

I said in my previous post that contrary to the impression created by O’Neill Salm has engaged with Kuhnen’s work in considerable depth and most certainly was not “quote mining” a single sentence. Here is a list of all of Kuhnen’s works consulted by Salm from the bibliography of his second book, NazarethGate:

Kuhnen, H-P.

1986. Nordwest-Palästina in hellenistisch-römischer Zeit. Bauten und Gräber im Karmelgebiet. Weinheim: VCH Verlag.

1989. Studien zur Chronologie und Siedlungsarchäologie des Karmel (Israel)

zwischen Hellenismus und Spätantike. (Tübinger Atlas zum Vorderen Orient. Beiheft B 72.) Wiesbaden.1990. Palästina in griechisch-römischer Zeit. (Handbuch der Archäologie. Vorderasien II,2.) München: C. H. Beck.

1994. Mit Thora und Todesmut: Judäa im Widerstand gegen die Römer von

Herodes bis Bar Kochba. (Führer und Bestandskataloge III.) Stuttgart: Württ. Landesmuseum .2002. “Bestattungswesen Palästinas im Hellenismus.” In: Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart (Göttingen), pp. 211 f.

2007. “Grabbau und Bestattungssitten in Palästina zwischen Herodes und den Severern.” In: A. Faber, P. Fasold, M. Struck, M. Witteyer (Eds.), Körpergräber des 1.–3. Jh. in der römischen Welt. Kolloquium Frankfurt am Main 2004. Frankfurt: Schriften des Archäologischen Museums Frankfurt am Main, 57–76.

2009. (with W. Zwickel): Archäologie und Politik im Land der Bibel: 60 Jahre Gründung des Staates Israel. (Kleine Arbeiten zum Alten und Neuen Testament). Mainz: Spenner.

Having finally caught up with Tim O’Neill’s October 2019 post on his History for Atheists blog, JESUS MYTHICISM 5: THE NAZARETH “MYTH”, I have decided to address a new point he makes since I last responded to his Nazareth assertions. Most of his October post is a rehash of what I demonstrated was erroneous in More Nazareth Nonsense from Tim O’Neill. But he has added a new point in an apparent attempt to refute at least one key part of my original criticism and it is that new point that I address here.

I have invited Tim O’Neill to discuss his criticisms on condition that he refrain from abuse and insult. He has responded by declaring I am not worth engaging with because I resort to “nitpicking”, otherwise known as “fact-checking”. Perhaps he will see this post as another example of “nitpicking”, this time in response to his claim that René Salm has based a key part of his argument on a mistranslation of a single sentence in Hans-Peter Kuhnen’s Palästina in griechisch-römischer Zeit.

Salm argues that there is no secure archaeological evidence published in the scholarly literature that enables us to date a settlement in Nazareth at the time of Jesus. The evidence for a settlement in Roman times only begins to appear from the mid or late first century CE. If the kokh tombs around Nazareth could be dated to the early first century then there would be a reasonable case for Nazareth being occupied at that time.

Kokh tombs were known around the Jerusalem region long before and during the time of Christ but Salm insists that they did not appear in Galilee until towards the end of the first century.

Salm has used Kuhnen’s work to argue that it is a mistake to use the dates of Jerusalem sites for the Galilee region. The kokh tombs appeared in Galilee much later than they did around Jerusalem, he says.

Here is the section of Tim O’Neill’s rebuttal of René Salm’s argument that I want to address.

Kokhim of this kind date from as early as 200 BC, but Salm insists that while they were used this early elsewhere in Palestine, they only came to be used in Galilee much later. For this he depends heavily on a single quote from German archaeologist Hans-Peter Kuhnen in his Palästina in griechisch-römischer Zeit (München: C.H. Beck, 1990). There Kuhnen discusses the origin and spread of kokhim in Palestine, appearing under the Hasmoneans and coming to dominate the style of tombs around Jerusalem by the time of Herod. He goes on to say (in Salm’s translation):

Apparently only later, from approximately the middle of the first century after Christ, did people begin to build kokh tombs in other upland regions of Palestine, as seen in Galilee at Huqoq, Meron, H. Serna and H. Usa. (Kuhnen, p. 254, in Salm, p.159)

Salm concludes from this that “kokh tomb use spreads to Galilee only after c. 50 CE” (p. 159), which he feels pushes the dates of the tombs in the Nazareth valley safely away from the period his theory needs to avoid.

But Kuhnen does not say that they did not reach Galilee until around the mid century: he specifies the “mountain regions of Palestine” (“Bergregionen Palästinas” in Kuhnen’s original German) and then gives examples of sites from the very north of Upper Galilee, in the mountains close to the modern Lebanon border and far from the lowland region in which Nazareth sits. Salm chooses to ignore where the illustrative examples Kuhnen are, translates “Bergregionen” as “upland” rather than “mountainous regions” or “mountain regions” (because the low-lying Nazareth region is not remotely “mountainous”) and so decides Kuhnen is saying kokhim did not reach Galilee generally – lower or upper – until “c. 50 CE”. Once again, he twists the scholarship and so shapes the evidence to fit his conclusion.

O’Neill, Tim. 2019. “Jesus Mythicism 5: The Nazareth ‘Myth.’” History for Atheists (blog). October 30, 2019. https://historyforatheists.com/2019/10/nazareth-myth/.

(My bolded highlighting of O’Neill’s words that I will show are “misleading” at best.)

O’Neill has only quoted a snippet of Salm’s relevant text and he has even misrepresented Kuhnen’s original passage. I don’t believe O’Neill did either of these things with deliberate dishonesty. I think he is so convinced that Salm is a fraud for daring to question the mainstream biblical scholars that he has only glanced at both Salm’s and Kuhnen’s words and once he thought he saw enough to “prove” his point he looked no further. It is “human” to see what we expect and want to see. He relies upon Salm’s translation of a critical passage so it appears he has not even consulted Kuhnen’s work for himself.

To his credit Salm quotes the original German of the section he translated so readers can hold him to account. Here is Salm’s complete quotation of Kuhnen:

15 Schiebestollengräber, die unter den Hasmonäern allmählich die älteren Kammergräber ersetzt hatten, beherrschten auch nach der Thronbesteigung des Herodes fast mit Ausschliesslichkeit die Friedhöfe der Stadt… Auch im jüdisch besiedelten Umland Jerusalems entstanden unter Herodes und dessen Erben Gräber des Schiebestollentyps, beispielsweise in Tell en-Nasbe und in el-‘Ezariye (Betanien) … Anscheinend noch später, etwa ab der Mitte des 1.Jh. n.Chr., begann man in den anderen Bergregionen Palästinas Gräber mit Schiebestollen anzulegen, was für Galiläa Huqoq, Meron, H. Sema und H. Usa… belegen.

Somit ist anzunehmen, dass Schiebestollengräber während des 1.Jh. n.Chr. in allen Landesteilen westlich und östlich des Jordan in Mode kamen… (Kuhnen 254–55).

(Salm, 159)

Kokh tombs [Schiebestollengräber], which under the Hasmoneans gradually replaced the older chamber tombs, also dominated the graveyards of [Jerusalem] almost with exclusivity after the accession of Herod… Under Herod and his heirs, the kokhi type of grave also appeared in the Jewish-populated surroundings of Jerusalem, for example, in Tell en-Nasbe and in el-‘Ezriye (Bethany)… Apparently only later, from approximately the middle of the first century after Christ, did people begin to build kokh tombs in other upland regions of Palestine, as seen in Galilee at Huqoq, Meron, H. Sema and H. Usa…

So it is evident that during the first century after Christ kokhim came into fashion in all parts of the land west and east of the Jordan…15

(Salm, 159. My bolded highlighting)

O’Neill failed to quote the last sentence Salm translates from Kuhnen which underscores Salm’s reading of Kuhnen’s point: kokh tombs were not known outside the Jerusalem region [i.e. not only in northern Galilee] until around the middle of the first century CE and not before. O’Neill wrongly claimed Salm said the kokh tombs were used everywhere else in Palestine except Galilee in the early first-century thus making his claim look like special pleading. He stopped short of quoting the sentence that flatly contradicted and exposes his misrepresentation of Salm’s argument.

O’Neill further infers that Kuhnen only points to sites in the “very north of Upper Galilee, in the mountains close to the modern Lebanon” that were the late borrowers of kokh tombs. That is flat wrong as we see in Response #2.

The four sites listed by Kuhnen are not, contrary to O’Neill’s assertion, “in the mountains close to the modern Lebanon border”. Two of them are; the other two are further south and on lower ground even than Nazareth.

Huqoq — not far from the “Sea” of Galilee, ca 30 metres above sea level

Meron — mountainous region in the far north, ca 600 meters above sea level

Khirbet Sema — mountainous region in the far north, ca 600 meters above sea level

Horvat Usä — further south, approx 8 kilometres east of Acre, about 30 meters above sea level

How “mountainous” is Nazareth by comparison? It is approx 350 meters above sea level.

But O’Neill has apparently not taken the time to consult Kuhnen’s book as Salm obviously did. Salm appears to have absorbed and incorporated Kuhnen’s intent from his larger argument as we shall see.

We now enter some serious “nitpicking” (“fact-checking”) with a look at the intent and thrust of Kuhnen’s discussion. Salm only quoted the first half of examples Kuhnen provided to illustrate his point about the apparent delay in the spread of kokhim tombs. The other half listed sites south of Galilee — in the region of Samaria.

[only later. . . as seen in] Galilee Huqöq, Merön, H. Sema and H. Usä, for Samaria Samaria-Sebaste, ‘Ar’ara, Sīlet ed-Dahr and Wädi Bedän.

(Kuhnen, 255)

So Kuhnen is saying that the spread of the kokhim tombs spread not only to northern Galilee but to Samaria as well quite some time after they became common around Jerusalem. (For the sake of completeness of comparisons I have added the elevations.)

‘Ar’ara — ca. 150-200 m

Sīlet ed-Dahr / Silat ad-Dhahr — ca 400 m

Wädi Bedän — 200 m

So now the map looks like this and Salm’s point about the kokh tombs appearing in Nazareth well after they were familiar around Jerusalem looks even more reasonable. Continue reading “Tim O’Neill Misreads (Again) the Evidence on Nazareth”