Continuing the series on Nanine Charbonnel’s Jésus-Christ, sublime figure de paper . . . .

Continuing the series on Nanine Charbonnel’s Jésus-Christ, sublime figure de paper . . . .

–o–

John the Baptist

Maybe I’m just naturally resistant to new ideas but I found myself having some difficulty with Nanine Charbonnel’s [NC] opening stage of her discussion about John the Baptist. (Recall we have been looking at plausibility of gospel figures being personifications of certain groups, with Jesus himself symbolizing a new Israel.) NC begins with an extract from Maximus of Turin’s interpretation: by cross-referencing to Paul’s statements that the “head of a man is Christ” (1 Cor. 11:3) Maximus concluded that the decapitation of John the Baptist represented Christ being cut off from the adherents to the Law, the Jews. Without the head they were a lifeless corpse.

We may not like that interpretation but at least Maximus recognized something symbolic about John the Baptist. As NC reminds us, he was the one who greets the messiah from his mother’s womb (Luke 1:41), the one who asks questions designed to recognize Jesus, the one who acts out Elijah’s confrontation with the lawless Jezebel and king Ahab. Even if we accept the entry about John the Baptist in Josephus as genuine and acknowledge that there was a historical “John the Baptist”, this person is depicted in symbolic roles in the gospels.

NC has more to say but permit me to give my own view, or perhaps a mix of my own with NC’s. John the Baptist is presented initially in the physical image of the arch-prophet, Elijah, and is calling upon all Israel to repent and prepare for the messiah. They all come out into the wilderness to do so. In Luke’s gospel when different groups (soldiers, tax collectors and others) ask John what they should do John replies with the fundamental spiritual intent of the law in each case: be merciful. Surely this is all symbolic of the Law and Prophets being the articles of the covenant made between Israel and God in the wilderness, and just as the early Christians found Jesus predicted in the prophets so John, the final prophet, points them to Jesus the messiah. Later we find the same prophet asking Jesus if he is the one, with Jesus replying with signs as recorded in the Prophets to assure him. John, meanwhile (as NC herself notes as significant), is martyred just as many other prophets before him, and just as Jesus himself will be. The tale is surely told as symbolism and the character John as a literary personification. Jesus emerges from the Prophets. It is the Prophets who all point towards Jesus Christ.

So when John says he is not worthy to baptize Jesus, he is saying that Jesus is greater than the Law and Prophets. Jesus, however, replies that he has come to submit to the Law and Prophets. His baptism represents the emerging in his full spiritual reality the new Israel, the one prophesied in the prophets. This is not the baptism described in Josephus. It is a baptism of repentance, of preparation for the Christ.

The absence of biographical or other historical information is telling. We only have details that call out for symbolic interpretation. The reason each evangelist can modify the narrative is not because they were working with historical data but entirely in their own imaginative interpretation of the way the Prophets pointed readers to Christ.

“John” and Peter race to the tomb

The famous Gregory who became the Pope in the sixth/seventh century identified a possible symbolic meaning of the Gospel of John’s account of John and Peter running to the empty tomb. Quoted by NC, Gregory sought a meaning in John arriving first at the tomb but not entering, with Peter coming later yet being the first to enter. John was interpreted as the Synagogue, the Jews, who had “come first” to Christ, but failed to “enter”. Peter, representing the gentiles, arrived later but was the first to believe. [See Gregory the Great Homily 22 on the Gospels; see also comments below for further discussion]

The two were running together, but the other disciple outran Peter and reached the tomb first. He bent down to look in and saw the linen wrappings lying there, but he did not go in. Then Simon Peter came, following him, and went into the tomb. He saw the linen wrappings lying there, and the cloth that had been on Jesus’ head, not lying with the linen wrappings but rolled up in a place by itself. Then the other disciple, who reached the tomb first, also went in, and he saw and believed . . . (John 20:4-8)

Interesting possibility. But if the “beloved disciple” is rather meant to be an unfalsifiable witness (and he, not Peter, is said to be the one who believed), it is hard to identify the same with the “Jews of the synagogue”. On the other hand, given what we know of Peter as the apostle to the gentiles, the one who stands between Jews and gentiles (hence his “double-minded” reputation?) something along the lines of Gregory’s interpretation does have some appeal.

Other points to consider, as per NC: John (meaning God is gracious) does have a sound similarity to Jonah, another representative of Jews in the old story. (Then we also have Peter being identified in the Gospels of Matthew and John with the son of Jonah.) NC promises to return to Peter in the last chapter. I will be patient.

Again, we have details that are not typically found in biographies. Recall the same point (especially with respect to the Gospel of John) in How the Gospels Became History. Such details appear pointless in themselves; they scream out for symbolic interpretation — and many ministers and preachers have understood this point well enough to prepare many sermons drawing out various meanings for their congregations.

The Twelve Apostles: the twelve tribes of Israel

This one is easier. The twelve patriarchs in Genesis are treated as symbolic representatives of the tribes that bore their names. I think many of us have seen in the Twelve Disciples a new founding group of the “new Israel”.

NC sees three principles underlying any interpretation of the Twelve.

1. Some clues of collective symbolism are given even with the twelve disciples: Matthew the publican, another is a Canaanite or zealot. Simon (or Shimon = “one who has heard”) is the son of Jonah. (He was later renamed as a “stone” or “rock”. Jonah means “dove” and we are of course reminded of the OT prophet. The symbolism of a dove? My attempt at a translation of NC’s explanation:

Now, the name of the prophet Jonah [=Dove] symbolized the Jewish community immersed in the diaspora to preach the word of God; faithless to his mission, he rediscovers it through the shipwreck at sea, which evokes the power of evil and death. Before being the stumbling block and at the same time chosen as a cornerstone, Simon is therefore the Jewish people being chosen to speak to the gentiles.

Likewise with the first two disciples called. They are brothers, Andrew and Simon. Andrew means “man” in Greek. We have the first calling of disciples being a symbolic narrative of the calling of gentiles (Greeks) and Jews as brothers (NC, p. 239).

2. The characters obey the meanings of their names. Again a rough translation of NC:

We never notice:

– that the full Greek surname of Judas is Ioudas Simonos Iskariōtou (John 6:71). This surname is made up of the names of three sons of Jacob

– all Leah’s sons – . . . Judah, Simeon and Issachar,

– that at the time of Jesus the family of the high priest was made up for two centuries of the descendants of Simeon the Just,

– and that Peter’s full Greek name is Simon, called Cephas. Now, this Simon Cephas denies Jesus to Caiaphas, the high priest.

Judas and Peter are both Simon (name of the lineage of the high priest), both in connection with the high priest (in his courtroom a denial and a betrayal), one focused on lies, the other on betrayal . . . . These two really have things in common . . . . and both disappear from the story at about the same time, one on betrayal, the other on a lie (Peter will reappear after the Resurrection of Jesus).

The names may be fleshed out from Hebrew counterparts (e.g. James from Jacob) but they may also be crafted anew as Apollonius of Tyana appears to have been a work of fiction. (NC refers to a work by Louis Benoit that notes similarities between the brother of Jesus, James the Just, and Apollonius of Tyana in writings of Eusebius, one about James the Just and another against the author the story of Apollonius of Tyana.)

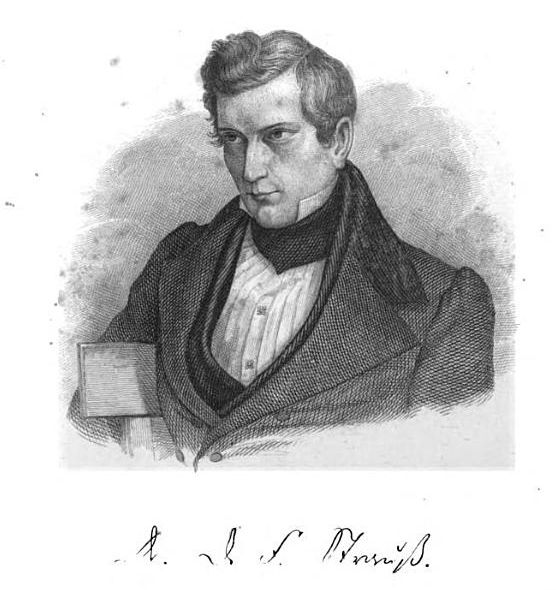

Further, NC raises a point singled out by David Friedrich Strauss: the curious fact that through the New Testament, for the same name we have a multitude of characters.

The real perplexity in the matter, however, originates in this: that besides the James and Joses spoken of as the brothers of Jesus, two men of the same name are mentioned as the sons of another Mary (Mark xv. 40, 47, xvi. 1, Matt. xxvii. 56,) without doubt that Mary who is designated, John xix. 25, as the sister of the mother of Jesus, and the wife of Cleophas: so that we have a James and a Joses not only among the children of Mary the mother of Jesus, but again among her sister’s children. We meet with several others among those immediately connected with Jesus, whose names are identical. In the lists of the Apostles (Matth. x. 2 ff., Luke vi. 14 ff.) we have two more of the name of James: that is four, the brother and cousin of Jesus included; two more of the name of Judas: that is three, the brother of Jesus included; two of the name of Simon, also making three with the brother of Jesus of the some name. The question naturally arises, whether the same individual is not here taken as distinct persons?

(Strauss, Life of Jesus, I, iii, 30)

NC’s comment: if such a multiple use of names undermines historicity, it does support the possibility of a kind of evangelist midrash at work. Is the reader meant to combine the names into one? Something does look odd.

3. Persons appearing as doublets, sometimes as pairs, sometimes opposites

So we have to Jameses. One major and the other minor. Two Judes, one Iscariot, the other son of Thaddeus (a “chest”). Two Simons, one Simon Peter, the other Simon the Zealot. In (with?) John we have Thomas, the Twin. In that latter instance we have a positive and negative character, one who believes quickly and the other reluctant to believe.

We have pairs of names in the same role. The two sons of Zebedee, James and John, appear symbolically to take the place of the two thieves either side of the crucified Christ. They asked to be at Jesus’ right and left, and Jesus promised they would, and see his glory. They saw his glory at the Transfiguration. For a fuller discussion, perhaps with the assistance of Google Translate, see James and John, Like Two Thieves . . .

We have pairs of names in the same role. The two sons of Zebedee, James and John, appear symbolically to take the place of the two thieves either side of the crucified Christ. They asked to be at Jesus’ right and left, and Jesus promised they would, and see his glory. They saw his glory at the Transfiguration. For a fuller discussion, perhaps with the assistance of Google Translate, see James and John, Like Two Thieves . . .

Again, we have Matthew and his other apparent namesake Levi, a son of Alphaeus. (I once struggled with this curious detail in an earlier post, The Call of Levi not to be one of the Twelve.)

What of the three inner disciples, Peter, James and John. NC links them with the three sons of Leah, three of the twelve tribes of Israel. I have difficulty seeing that one, but I copy here NC’s footnoted quotation:

Three Apostles seem to be set apart for a particular initiation … They are Peter, Jacques and John: they are the ones who attend the Transfiguration (Luke 9-28); in Luke (9-54) we read that Jacques and Jean know how to make lightning fall; in Luke (22-8) it is Peter and John who are sent to prepare the feast of the Passover; in Luke (8-51) only Pierre, Jean and Jacques must attend the resurrection of the twelve year old girl. Pierre, Jean and Jacques correspond to Ruben, Juda and Lévi all three sons of Léa …

On the breastplate of the High Priest their stones engraved with their names are at the head of the three rows of four … But above all we must remember that these are the three elders of Jacob-Israel(Jude-Simeon being excluded by the curse due to the Sichem affair). Thus nothing is done at random in the choice of the Apostles. (https://gallican.org/douze2.htm)

From Simon to Peter

Another interpretation and one that I have less difficulty with is found not in NC’s book but in a more conventional study of the Gospel of Mark. It is in Sowing the Gospel by Mary Ann Tolbert. She writes of the reason Simon was named Peter:

The first disciple listed, Simon, whose name is additionally set off from the rest grammatically, is nicknamed “Peter” (Πέτρos) by Jesus, but the narrator offers no further elaboration. The explanation of the nickname will come in the parable of the Sower when the second type of ground upon which the seed is sown is described as πετρῶδης (και άλλο ἔπεσεν ἐπὶ τὸ πετρῶδες, 4:5). Simon Πέτρos, Simon the “Rock,” signals the basic relationship of the disciples to the πετρώδης, the “rocky ground.” Unlike Matthew and Luke, who identify the leading disciple as Simon Peter very early in their narratives, thus obscuring the correspondence between Simon’s nickname and the second type of ground in the parable, Mark has unfailingly and with utter consistency referred to the leading disciple simply as Simon up to Mark 3:16. From 3:16 to the end of the Gospel, he is just as consistently called Πέτρos. This striking change of name is then followed in close proximity by the description of the “rocky ground” in Mark 4:5, and the resulting rhetorical paronomasia, or word-play, establishes the bond between Πέτρos and πετρώδης, the “Rock” and “rocky ground.”

In fashioning such a play on words, Mark has also implicitly developed a kind of etiological legend for the origin of Simon’s nickname: Jesus names him “Rock” because of his hardness; he typifies hard and rocky ground, where seed has little chance of growing deep roots. For the Gospel of Mark, hardness, especially hardness of heart, signifies the rejection of Jesus’ word (e.g., 3:5; 6:52; 8:17). For the Gospel of Matthew, the hardness of rock suggests a different image altogether.

(Tolbert, 145-46)

Which brings us to the name Mary. . . .

Continuing . . .

Meanwhile, here are some of my earlier posts addressing curiosities in the names we find in the gospels:

The Twelve Disciples: their names, name-meanings, associations, etc

More Puns in the Gospel of Mark: People and Places

Tracing the evolution of the Twelve Apostles from monkey rejects to angelic pillars.

If Adam and Eve are metaphors why not . . . . ?

Charbonnel, Nanine. 2017. Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier. Paris: Berg International éditeurs.

Strauss, David Friedrich. 1892. The Life of Jesus Critically Examined. 2nd ed. London: Swan Sonnenschein.

Tolbert, Mary Ann. 1989. Sowing the Gospel: Mark’s World in Literary-Historical Perspective. Minneapolis: Fortress Press.

“Des Douze Tribus d’Israël Aux Douze Apôtres – 2.” 1983. 1983. https://gallican.org/douze2.htm.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider donating to Vridar. Thanks!

Nice post, thank you! Re “Gregory sought a meaning in John arriving first at the tomb but not entering, with Peter coming later yet being the first to enter. John was interpreted as the Synagogue, the Jews, who had “come first” to Christ, but failed to ‘enter’.” Peter, representing the gentiles, arrived later but was the first to believe.” So, in the sixth-seventh century an interpretation is offered. But this hardly can be the reasoning behind the author writing the gospel that way. At that time, there were Jews who were Christians as well as gentiles who were. Is the gospel from a Pauline sect that was catering to gentiles, surely not all of them, certainly nor the gospel we call Mark.

So, this sounds like spin to me, it sounds like a convenient interpretation that makes a point that the author wanted to be made. It also backs up the divinely inspired writing meme and all of that.

The Disciple whom Jesus Philia was Lazarus not John.

Or Paul or Mary or Thomas or Nathaniel or Mark . . . . 🙂

Or . . . . a fiction to imbu the gospel with an unfalsifiable authority:

Once More: The Fictions of the Beloved Disciple and Johannine Community

No, I mean the Internal Evidence of the text of the Gospel makes this issue no where near as Ambiguous as people want it to be. The Disciple whom Jesus Agape was Mary and whom Jesus Phileo was Lazarus, Chapter 11 spells that out in clear uncertain terms.

I don’t expect you be convinced that’s who actually wrote the Boo, but that is who the book is clearly claiming to be written by.

You will be interested in C.K. Barrett’s observation of the different words translated “love” in the Gospel of John:

and

Barrett, C. K. 1978. The Gospel According to St. John. Edition: 2. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 215, 584

See also https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/are-there-different-loves-in-john-21/

They are synonymous in terms of their basic meaning (as is Eros, this modern notion of different mutually exclusive words for Love didn’t exist tin antiquity) it is only in their usage as basically titles of specific people I make any distinction.

The ONLY time Phlia is used int his way of a person unnamed in the mediate context is the usage in chapter 20, which is further specified “the other Disciple whom Jesus loves” implying to me the usual Disciple whom Jesus loved was someone already there.

The words being interchangeable still doesn’t change that Chapter 11 narrows it down to the three Bethany Siblings. Jesus loved Everyone ultimately yes, but a special identifying an use after chapter 11 is clearly meant to be a reference back to chapter 11.

You see things much more “clearly” and “certainly” than I do.

@ Steve: Yes, I think the real significance in the narrative is that such a mundane event as two men running to a tomb told with such minutiae is not the sort of thing one finds in biographies or histories. It is the stuff of analogy, of symbolic action, and hence has attracted all sorts of “spiritual” interpretations.

If the original meaning is now lost to us, all the better for believers who can enter vicariously into the story and imagine all sorts of scenarios — as per the explanation of Sarah Miles Johnston.

I have a paper up on my academia.edu page arguing that the figure who ran with Peter to the tomb in Jn 20 is the apostle Andrew, not the apostle John. My paper is titled: “The Case of the Purloined Apostle: was the Beloved Disciple of the Fourth Gospel the Apostle Andrew?” But carry on! 🙂

It is an interpretation of the Fourth Gospel as reflecting second-century Rome (“Simon Peter”) versus Asia Minor (“Andrew”) competing authority claims. My paper made an internal argument that the beloved disciple continues the figure of Andrew and is other language for Andrew, and externally, that Andrew is the earliest apostolic-authority claim for Asia Minor churches, from Papias and the Muratorian Fragment. The issue becomes not historicity of these figures but an interpretation of rival and competing authority claims reflecting second-century ecclesiastical power issues. My paper argued that the role of Andrew of the eastern churches as superior to Peter, reflected in the Fourth Gospel, is in contrast to a marginalizing of Andrew compared to Peter in the synoptics, and for the same reasons. I wrote this argument in 1991.

Your view [link is to your academia.edu article] would make better sense of Gregory the Great’s view in his Homily on the Gospels. (I’ve added the link to Homily 22 in the post.) Peter goes in the tomb but it is his companion who is explicitly said first to believe. If that companion was the disciple representing the Greeks or gentiles more generally then we have in this race to the tomb episode the same message said to be in other scenes in the Gospel of John: e.g. the wedding at Cana, another that may indicate the necessity of the gentiles as a group preceding the Jewish nation in order of faith.

Simon Peter is named Petros/rock after Jesus’ and his father, Joseph Caiaphas/kepha (rock in Aramaic), so a “chip off the old block (or rock).” Caiaphas was a nickname used for Joseph presumably because of his lengthy tenure as high priest. Note that he was not referred too as Joseph ‘ben’ Caiaphas, as would have been expected, and that Josephus refers to him as Joseph “called” Caiaphas (the rock).

It must be remembered that under Roman domination, anything written by subjugated societies, if it contained anything of a political nature, would have needed to be written in code (allegory) which the Gospels are. This would have been true from 63BCE to the 4th century. Such writings might seem fictional or mythical accounts to the uninitiated, especially today and even during Jesus’ life, as he comments in the Gospels.

So the multiple names do refer to singular people; Joseph, Jesus’ father and Joseph of Arimathea and Joseph Caiaphas all refer to the same man, Jesus’ father (see the Miriam ossuary for the reference to Jesus as Caiaphas’ son). All three Josephs played significant roles in Jesus’ life. As did Mary, his mother, Mary Magdalene, and Mary of Bethany. They all refer to Jesus’ mother (see the allegorical Story of Aseneth to understand that Mary Magdalene was Jesus’ mother where Aseneth also sweats blood under duress). And so on and so forth.

It was essential when writing the Gospels to obscure the identities of the people involved. Hence there were no biographical details of Jesus’ life and no physical description. Using multiple names for individuals also tended to make determining their true identities more difficult, as has been the case for two thousand years. If, as a political revolutionary, you were having propaganda written about you, would you expect that the writers would include your true biographical details and a full physical description of you?

So CN is right to wonder whether the multiple names referred to singular people. They do. And for a good reason.

I invite you to read and think about my recent posts on logical errors of historians. You have committed a few yourself here.

But on a point of fact, you write:

I keep seeing that idea floating around. It is simply not true. Historians were perfectly free to write critically of events under a previous emperor. There was no problem with being critical of a cruel governor under the emperor Tiberius at the time the gospels were written. One could even be critical of governors at any time, actually — remember Philo going to Rome to report the misdeeds of a governor in Alexandria.

NC (not CN) has a starkly different explanation for the names from your view. There is no comparison. Like one explaining disease as the result of viruses and another arguing they are the result of Apollo’s arrows.

Perhaps I didn’t make myself clear; anyone writing political PROPAGANDA during Roman occupation suggesting revolt would have come under immediate scrutiny of the Roman officials. I don’t know that criticism of previous emperors or current governors falls under that category.

Jesus was the presumed king of Judea, not some historian. For propaganda to be written about him would have required that it be allegorical, not factual. He was preaching revolution. To paraphrase Jesus: those in the know will get what I am saying, those who aren’t will not. Presumably, those in the know would educate those who weren’t.

I have read your posts about logical errors of historians. They were very interesting but missed the point. The point of historical reconstruction from available evidence is to build a case that best suits the evidence. It is a FIRST step in analyzing historical events. After having read your posts, I began to wonder if we could really accept as historical anything that transpired before the advent of TV and video tape. That’s not sarcasm, that is a serious question.

The idea of a mythic Jesus didn’t just spring up, fully formed out of thin air. It has been developed over time, with revisions as scholars continue to analyze the data. And those scholars have made many of the same logical fallacies that you have posted about.

I notice that often the mythicists present the either/or argument for Jesus: either he is a myth or he was historical. But those are not exclusive points of view since both could be true. Myths often spring from real people.

The main problem with the mythicist point of view is that while all of those arguments could be true (and I think many are) none of them negate the historical Jesus, none of them make an argument that says Jesus could not have existed. So it is a preferential view. People believe it because they want to believe it, not because it refutes an historical Jesus.

And I disagree that NC’s (not CN; late night typo) view and mine are starkly different. They both are concerned with the multiplicity of names in the Gospels as a means of understanding the historicity of those writings. If they are used in the sense that NC puts forward, the people they refer to might be less likely to be historical figures. If, on the other hand, they refer to the singular individuals as I suggest, they may represent historical figures. We have different views of the same evidence, just as atheists and theists have starkly different and opposing views on the same subject; does god exist? Are you suggesting that our separate views cannot logically be presented together?

Also, I notice that your responses to my posts tend to be ad hominem rather than refutations of of the evidence I present. Is there any reason to suppose that what I have suggested CANNOT be possible?

Not so allegorical in John. And not so allegorical according to the sign Pilate placed at the top of his cross.

And that’s the very point I address in “If it fits — be careful”: https://vridar.org/2020/04/14/logical-fallacies-of-historians-if-it-fits-beware/

Historical reconstruction must go beyond being satisfied with any reconstruction that “fits” or “best suits the evidence”. Actually, to say a reconstruction “best suits” the evidence requires one to address competing reconstructions with the same data (“data” is a better word than “evidence”; evidence implies support for your theory; data is more neutral, I think). There are many reconstructions from the available data (much more than what you use) that are far better “suits” or “fits” than your reconstruction.

It’s a question I have attempted to address in other posts. It is also one that many historians themselves have written about. I have explained why historians can know certain events happened by referring to their works. I have also explained from their works why they cannot know many things.

You have misunderstood the dichotomy here. Everyone accepts, mythicists and believers alike, that myths often spring from real people. That is never denied. The mythicist says there was no real person behind the myths (even though theoretically there could have been).

This is another fallacy I may write about. Just because something is possible, or even plausible, does not make it a “historical fact”. Many things are possible and plausible. We might even build up a nice reconstruction from the data to describe how they happened. But that is all the work of our imaginations playing with the data — we need to have ways to test those theories. Example: how could a historian decide whether a man really did walk on the moon? How could she know if it was fact or a trick concocted in a movie studio?

Yes.

So you’re saying that the sign Pilate placed on Jesus’ cross was NOT allegorical? It was historical? That would tend to refute the mythicist theory, wouldn’t it? By saying that, you are suggesting that an historical Jesus actually existed.

By the time Jesus was arrested Pilate must have known that Jesus was fomenting rebellion by claiming his kingship of Judea.

The allegorical method was used for Jesus’ parables and miraculous healings, to hide his true intent of reclaiming his crown and starting a rebellion against Rome. Not every word or event in the Gospels was intended to be allegorical.

Please name the “other reconstructions” from the available data that better suit an historical reconstruction. Perhaps I’ve missed something.

“Everyone accepts…” is a very broad generalization unless you have done an in-depth survey. If you have, please send it along.

If , as you suggest, everyone knows that a real person might have been the catalyst for a mythical Jesus, the most mythicists could claim, I think, is that myths grew up around a person named Jesus, which is not the same as saying Jesus was a myth, which many mythicists claim. That still allows for a search for the historical Jesus.

Myths most certainly would have arisen around a man who seemingly survived a crucifixion and then disappeared as people sought explanations for such an occurrence. Which is exactly what happened. Some people believed in the resurrection, some people believed his body was stolen, some believed Jesus was a spiritual entity, and some believed it was a mythical event. But the fact, as you say, that the titulus above Jesus on the cross, indicated that he was king of the Judeans, tells us something about the historical man.

Why wasn’t Herod Antipas, who wanted to be acknowledged as king, not crucified while Jesus was? Because Antipas was an Herodian and Jesus was a descendent of David. Being of the Davidic line was much more of a threat to Roman power than was an Herodian.

Rather than a simple “Yes”, please explain why you find it illogical that NC’s and my views on the multiplicity of names cannot be presented together. Thanks.

If the idea of “possible, or even plausible” as a means of beginning an historical reconstruction are subject to doubt, then as I said, the idea of historicity any time before we could visually record actual events, becomes suspect, and even then, visual records can be manipulated. So what do you propose? All scientific examination begins with observation and theory. The same is true of history: observe the available data and imagine a theory that best describes the data. Then gather as much supporting data as you can and test the theory to see if it stands up. Then test the theory against other theories to see which is more logical. That’s exactly how I’ve approached the historical Jesus. The mythic Jesus theory has too many major holes in it to be a logical explanation of Jesus.

The comments I have made in response to your posts represent only a small fraction of the data that supports my theory. As a suggestion, you might want to know more about my claims to fully understand my comments. I contend that my theory best suits all the available data. Again, please send along even one theory that better suits the data and why you think it does. I have spent well over a decade searching for just such a theory so that I could put my theory aside and as yet I have not found such a theory. If you know of one I would love to see it.

I find your comments to be too laden with a lack of awareness of the details of views other than your own, lacking in the most fundamental level of reading comprehension of ideas other than your own (one almost has to think you have not read carefully other works you seem to dismiss), so replete with the logical fallacies that you say “miss the point” with respect to your views, that I cannot bring myself to reply in detail to specific points you make. I have no problem with anyone not understanding something or making mistakes — I’m as guilty as anyone in those areas — but you come across as arrogant and crudely aggressive with a clear refusal to accept anything but the correctness of your own views.

You may have heard mention of the Dunning-Kruger Effect before. You will find this comment offensive, I know, but I have given you a pretty good run on this blog and I have tried to point out each of the following with examples to demonstrate over some period of time with you. You have to accept where you stand here and how others, especially I, see your comments. I think you would be happier if you do not waste any more of your time here.

The most unfortunate thing is that you will interpret this comment as my inability to answer your challenges and as an implicit recognition of the superiority of what you are saying. Please accept that you will never find satisfaction here.

I never imagined I would find satisfaction on your site, but I did imagine that I would find valid, coherent rebuttals of my arguments. Those were what I was hoping you could provide. Although you claim to have pointed out logical fallacies in my posts, you have not. Nor did you refute any historical data I presented, except through ad hominem attacks.

Sorry you can’t provide them.

And yes, I do interpret your lack of response as your inability to answer my challenges. There is no other way to interpret it considering the length you often go to in order to refute others.

Superiority has nothing to do with this, except perhaps in your case, judging by your response.

The Disciples Peter, James, and John represent… the Apostles Cephas/Peter James, and John before they represent anyone else as well! 🙂 If James is supposed to represent Levi, who does Levi represent? There are three Judases, “Twin, Twin” is one too. Are all the duplicated names meant to be single individuals? To the contrary; Simon Peter is probably a conflation of two individuals, the “pillar” Cephas and the subordinate Peter from Galatians. I think the all the names are symbolic at root, the duplication makes you go “Wait… What? That’s ridiculous”. That might be intentional to make you think there is something else going on and draw you in if you are the right person. They don’t actually want the seed to fall on stoney ground afterall. If the story was based on actual reality, I think it would be clear individuals have been bifurcated. Since it is fiction, why you would want to write your charcters like that I couldn’t begin to fathom.

Crack on, man; this is sterling stuff. I’m hoping it wiil generate sufficient interest for an English translation or if not that, at least get Francophones or bilinguals to buy the original and chip in here.