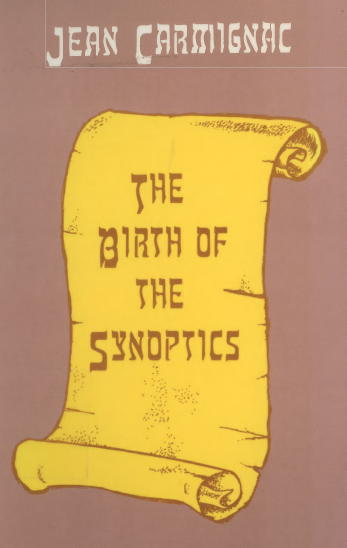

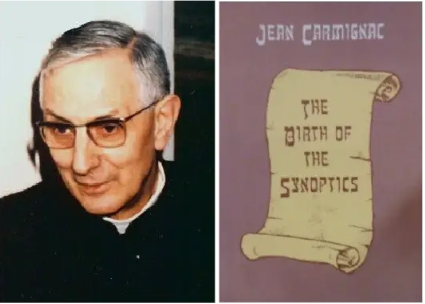

The arguments are not widely known so I am setting them out in a series of posts so we can at least begin to ask questions and think about them and have some idea of what questions to raise with specialist scholars. (All posts in this series are archived under the Carmingnac: Birth of the Synoptic Gospels tag.)

The arguments are not widely known so I am setting them out in a series of posts so we can at least begin to ask questions and think about them and have some idea of what questions to raise with specialist scholars. (All posts in this series are archived under the Carmingnac: Birth of the Synoptic Gospels tag.)

As pointed out recently, Jean Carmignac observes nine different types of Semitisms. That same post looked at many of the Semitisms in the #7 type that he believed to be significant for his hypothesis.

- Semitisms of Borrowing

- Semitisms of Imitation

- Semitisms of Thought

- Semitisms of Vocabulary

- Semitisms of Syntax

- Semitisms of Style

- Semitisms of Composition

- Semitisms of Transmission

- Semitisms of Translation

Here is what Carmignac says of the others (with my bolded highlighting):

1. Of Borrowing

e.g. In the Greek gospels we find words like amen, abba, alleluia, and words that transcribe Semitic expressions like messiah, sabbath, pasch, etc.

In themselves, these borrowed words prove nothing, since anyone can quote a few words from a foreign language . . . (p. 21)

2. Of Imitation

Specifically, thinking here of the authors of the gospels imitating the Greek Septuagint even where it translates obvious Semitic turns of phrase:

Each time that a turn of phrase in the New Testament reproduces a turn of phrase from the Septuagint, we will consider it as a possible imitation and, therefore, we will no longer attach any conclusive value to it. (p. 22)

3. Of Thought

Instead of a simple he came, he spoke, he saw, a Semitic phrase would appear as he got up and he came, he opened his mouth and he spoke, he raised his eyes and he saw.…

Quoting Joseph Viteau,

“One of the most characteristic marks of the language of the New Testament consists of a total inability to combine, synthesize, subordinate the various elements of thought, and, consequently, construct periodic sentences such as those which the literary language of classical authors presents. To this repugnance or to this inability corresponds a very noticeable tendency to dissociate the elements of thought in order to express them separately. . . . This characteristic of the Greek of the New Testament is to be found constantly in the general structure of the language. . . . Thus there has taken place what we refer to as the dissociation of the Greek language. For the Jew, it was an absence of association and of subordination, as in his own language. For the Greek it was a dissociation of his language as he wrote it himself.”

Carmignac concludes:

[T]his particular type of Semitism might be able to serve to determine the original milieu of an author, but it would not serve to determine the original language of a work. (p. 23)

4. Of Vocabulary

e.g.

Instead of saying citizen of the kingdom, invited to the banquet, condemned to Hell, man of good will, slave of the world, servant of the good, candidate for the resurrection, agent of evil, opposed to the Faith, one will say son of the kingdom (Mt 8:12; 13:38); son of the banquet (Mt 9:15; Mk 2:19; Lk 5:34); son of Gehenna (Mt 23:15); son of peace (Lk 10:6); son of this world (Lk 16:8; 20, 34); son of light (Lk 16:8; Jn 12:36; 1 Thes 5:5); son of the resurrection (Lk 20:36); son of perdition (Jn 17:12; 2 Thes 2:3); son of disbelief (Eph 2:2; 5:6; Col 3:6) and the excessively bubbling zeal of James and of John earns for them the surname sons of thunder (Mk 3:17).

Carmignac concludes:

[T]hese Semitisms ought not to be taken into account for they are vestiges of the language which is most familiar to the author not the proof that he actually used this language in the redaction of the work in question. (pp. 23f)

5. Of Syntax

Since syntax is the customary rule which governs the relationships of words among themselves, it supposes a deep knowledge of each language. The correct use of verbs, of prepositions, of conjunctions, of various complements (objects of verbs) is so complicated that it calls for and needs a very long period of practice in order to avoid committing a particular mistake, especially when the languages reflect psychologies as different as the Semitic psychology and the Greek psychology. An example which is quite simple: to say at the house of the king, the Hebrew (and in certain cases the Aramaic) suppresses the article before the first noun and always says at house of the king. A Semite who speaks Greek will therefore have the tendency to omit the article in this case and to preserve his familiar turn of phrase as we certainly meet many times in the New Testament. Another similar simple example: the verbs to say or to speak take the preposition which corresponds quite well to the Greek form, while in Hebrew (but not in Aramaic) they also take the preposition toward: and it is for that reason that we so often find in the Gospels, especially in Luke: to say toward someone or to speak toward someone. (p. 24)

Carmignac concludes:

In theory, they prove nothing about the original language since we can always suppose that the redactors of the Gospels underwent the influence of their mother tongue. However, when these mistakes in syntax go beyond that which is probable—even in the case of a writer who is not well acquainted with a language—we are led to suppose that they derive from a translator who was too slavish in his task, desiring to carbon copy, to the least detail . . . (p. 24)

6. Of Style

e.g.

Semitic prose is much more akin to the oral style than Greek prose, which is much more elaborate. It does not seek to construct sentences but more often is content with laying out several clauses joined together by a simple and. Monotony is no deterrent, whereas in Greek there is a tendency to seek variety. Moreover, it does not avoid the repetition of several words of the same root since these redundancies facilitate memory and provide more emphasis for the reciters of these accounts: the sower went out to sow his seed and while he was sowing . . . (Lk 8:5); I have desired with desire (Lk 22:15); they feared with a great fear (Mk 4:41; Lk 2:9); they rejoiced with a great joy (Mt 3:10).

Carmignac concludes:

But once again, no valid argument can be derived from these customary habits of style for a Semite could preserve them, even when he was expressing himself in Greek. . . .

We enter different territory when it comes to poetry, however, and here Carmignac writes

If the poems of the Gospels had been composed in Greek, they would have had to depend upon the laws of Greek poetry; but this is clearly not the case. The Benedictus, the Magnificat, the Our Father, the Prologue of John, the Priestly Prayer of John 17 do not respect any of these laws of Greek poetry; rather they are constructed according to the rules of Hebrew poetry. (p. 25)

There is another point, however.

In Hebrew, there is great preference shown for beginning a work or introducing a new development by wayyeht (and it came about); then follows an indication of time, which is generally an infinitive introduced by the preposition in (= in the doing of it, that is to say, while he was doing)’, the sentence is then continued by another verb, usually preceded by and. This turn of phrase is found almost 300 times in the Old Testament. The Septuagint then translates literally kai egeneto en tô (= and it happened in the doing), then it usually expresses the indication of time by an infinitive followed by its subject and by its objects, then it continues the sentence by kai [and) followed by another verb in the indicative. The result is as bizarre in Greek as it is in English: and it happened in the doing of it (this or that) and (such a person) said. . . . This barbaric turn of phrase is never found in the works of the New Testament which have certainly been composed in Greek: the second part of Acts,18 the Epistles and even the Apocalypse, but it is found twice in Mark, six times in Matthew and thirty-two times in Luke.

Carmignac concludes:

However, since this turn of phrase exists in the Septuagint, let us agree not to insist upon it and concede that it could have been inspired by a desire to imitate the Septuagint. (p. 26)

7. Of Composition

See A Semitic Original for the Gospels of Mark and Matthew?

8. Of Transmission

Mistakes are bound to happen when reading early Hebrew given that vowels are not represented in the text and several consonants are easily confused with one another.

Some indications of confusion concerning a Hebrew original:

In Mark 1:7 and Luke 3:16, John the Baptist says: I am not worthy to unfasten (lâshèlèt) the strap of his sandals, but according to Matthew 3:11 he says: I am not worthy to carry (lâs’ét) his sandals. . . .

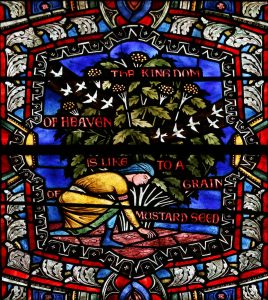

Then there’s that grain of mustard seed:

Then there’s that grain of mustard seed:

Matthew 13:32 and Luke 13:19 say that the grain of mustard becomes a tree, which is a definite exaggeration, for this plant hardly exceeds a meter and a half or two meters. Mark 4:32, on the contrary, says that it has branches that are so great that birds nest there. All would be explained if Mark, who seems to be inspired by Ezekiel 17:23, had rendered ‘NP (pronounce ‘anâph) branch, as in Ezekiel, and if a copyist prior to Matthew and to Luke had read ‘S (pronounce ‘ès) tree, since in the style of calligraphy in Qumran, the letters N and P, if they come together and touch one another, resemble the letter Ṣ. (p. 31)

Does Jesus begin to teach or begin to show?

In Mark 8:31 Jesus begins to teach (LHWRWT = lehôrôt) and in Matthew 16:21 he begins to show (LHR’WT = lehar’ôt). The two words are very easily confused with each other since, according to the style of calligraphy, in Qumran, the first could lose a W and the second its ’ so that each one would end up looking like LHRWT. (p. 31)

Did Jesus pass through the villages or the region of Caesarea Philippi?

Mark 8:27 says that Jesus passed through the villages of Caesarea Philippi and Matthew 16:13 the regions of Caesarea Philippi. The general meaning is the same, but the passage from one word to the other could have been brought about by the resemblance between QRYWT = qiryôt: villages and QSWWT = qesawwôt: regions, since Y and W are written almost in the same way. (p. 32)

Go to hell or be thrown into hell? Continue reading “Hebrew Hypothesis for Synoptic Gospels Continued”

Like this:

Like Loading...