Archaeologist Dr Ken Dark, in the Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society [BAIAS] (Vol. 26, 2008), wrote a 5 page review of René Salm’s The Myth of Nazareth: the Invented Town of Jesus (2008). I was led to this review after catching up with a discussion of Salm’s book on the Freethought & Rationalism Discussion Board.

Declaring the vested interests

Ken Dark begins by laying out the bias:

Salm then argues that this, in turn, discredits the New Testament account of the childhood of Jesus Christ, an argument that must have made the book attractive to its publisher, the ‘American Atheist Press’.

This is a reasonable point. On the other hand, interestingly, the same issue of BAIAS published a response by Salm to its previous issue’s “Surveys and Excavations at the Nazareth Village Farm (1997-2002): Final Report” by Pfann, Voss and Rapuano. This survey began:

For nearly two decades, the University of the Holy Land (UHL) and its subsidiary, the Center for the Study of Early Christianity (CSEC), has laboured to lay the academic foundation for the construction of a first-century Galilean village or town based upon archaeology and early Jewish and Christian sources. It was hoped that such a ‘model village’ would provide a ‘time capsule’ into which the contemporary visitor might step to encounter more effectively the rural setting of Galilean Judaism and the birth-place of early Christianity. At Nazareth Village this educational vision is currently being realized . . . (2007, V0lume 25)

So it looks like the battle lines are drawn: an archaeological project funded by “Holy Land” and “Christianity” interests and aimed at promoting a 3-D time capsule for lay visitors versus a publisher with a vested interest in discrediting the same faith.

Other contributions and reactions

René Salm’s published response to this Final Report of the Nazareth Village Farm surveys and excavations provoked significant reactions in the same BAIAS, among them a 22 page “Amendment” to the original Final Report. Clearly it would be a mistake to dismiss the amateur Salm as a fringe crank. His responses in the academic discussion list, Crosstalk2, some years ago also introduced him as someone whose knowledge and understanding of the archaeological reports deserve serious attention and responses.

I won’t mention this, or that, nor will I address something else, and especially not X or Y

Ken Dark’s review amusingly — and tellingly — consumes quite some space delineating all the points it will “not” address. Among several other inadequacies and errors, Dark “will not draw attention to mistakes of referencing, measurement, language or citation . . .” etc. Having set out a detailed backdrop of an error-laden, incompetent work, without any supporting references (because these are not what he will address), Dark delivers a few direct kicks:

This review will not draw attention to . . . . language . . . , although it is worth noting that Salm affords no equivalent courtesy to other scholars (for example, criticizing Bagatti’s English grammar on p.113).

Ouch. Ken Dark has inexcusably omitted Salm’s own explanation for his comments on this one particular instance of a grammatical inconsistency in Bagatti. The grammatical inconsistency is raised by Salm as evidence, in this particular context, of a less than forthright report of the exact nature of the evidence in question. He is not interested in discussing grammar. Salm is alerting readers to evidence that Bagatti knew he was being less than fully candid with his report:

We note, first of all, the incorrect English grammar. The subject is plural and two examples are given, but the verb is singular. It is of no moment whether the faulty grammar is due to the author or to the translator, for — since Bagatti nowhere claims Hellenistic structural remains — we here have the remarkable admission that the entire Hellenistic period at Nazareth is represented by only two pieces: an oil lamp nozzle, and number “2 of Fig. 235.” . . . . . A third surprise meets us when we compare the two artefacts. Incredibly, they are two versions of one and the same piece — represented once in a photo (Fig. 233 #26), and once again in a sketch (Fig. 235 #2). This may explain the singular verb is in Bagatti’s statement: the two pieces are one.

Ken Dark’s complaint that Salm is less than gentlemanly for stooping to correcting Bagatti’s grammar is a disingenuous avoidance — even a misrepresentation — of Salm’s discussion of the nature of the evidence and how it is misleadingly reported.

Disingenuousness #2

Dark follows up with a knife thrust at Salm’s supposed hypocrisy for doubting another scholar’s published work on Nazareth because the scholar in question lacks specific qualifications and experience, while Salm himself is not an archaeologist. “I will not judge Salm’s work on the same basis . . .” Once again Dark is being disingenuous. Here is Salm’s actual discussion of this point:

Besides his writings on Sepphoris, Strange has authored scores of archaeological reference articles on many sites in Palestine . . . . He has published extensively on Nazareth . . . . Other than Bagatti, Strange is arguably the most cited scholar on Nazareth. This is curious for two reasons: (a) unlike Bagatti, Strange received no academic degree in the field of archaeology . . . . and (b) Strange himself has never dug at Nazareth, nor has he authored a report dealing with material remains from the Nazareth basin.

Though very influential, Strange’s contributions to the scholarly Nazareth literature are limited to brief summaries of the site’s archaeology and history in reference articles and books. He is not in a position to offer us any new material evidence, and thus his opinions lie entirely within the range of the secondary Nazareth literature. Nevertheless, his views have radically departed from those of Bagatti and the Church, and have moulded the prevailing attitude in non-Catholic circles regarding Nazareth. . . . . . .

[I]t is surprising that archaeologists of the stature of Meyers and Strange would take a position in diametric opposition to the conclusion of the principal archaeologist at Nazareth, B. Bagatti. A remarkable feature of the Nazareth literature is that it has accommodated strikingly varied positions, none of which are dependent upon the archaeological record at all. (pp.137-140)

Dark suppresses the fact that René Salm is challenging Strange, and the surprisingly widespread influence of Strange’s interpretations, on grounds that his views stand in contradiction to the “material evidence” reported by the “principal archaeologist at Nazareth”.

Such is the disingenuity with which Ken Dark begins his review.

So by way of introduction, Dark misrepresents Salm for supposedly focussing on Bagatti’s grammar and supposedly complaining of Strange’s inability to offer new material evidence. As the quotations from Salm, above, demonstrate, Salm is actually addressing the lack of forthrightness with which the actual evidence is reported (not grammar per se, contra Dark), and the widespread acceptance of opinion and interpretation in place of material evidence as reported by “the principal archaeologist” (not Strange’s reliance on secondary literature per se, contra Dark).

1. Is it logically possible to show Nazareth did not exist at the time of Jesus?

This is the first of five themes of Salm’s The Myth of Nazareth that Ken Dark addresses. Dark quite logically and correctly points out that “it is not possible to show archaeologically on the basis of the available data that Nazareth did not exist in the Second Temple period (or at any other period), because the focus of activity at any period may be outside the — still few — excavated and surveyed areas.”

Dark is quite correct logically when he elaborates the above by pointing out that hypothetically archaeologists could all be digging at the wrong places entirely for the New Testament Nazareth.

It matters not how weak (or strong) the archaeological evidence is, one can always hypothesize that it is in the wrong place. True, true. So let’s not be so Bernard Woolley-like pedantic and instead let’s limit our discussion to the evidence at sites as they are published as supports of the New Testament Nazareth. Which, of course, is what we are all doing.

2. Hydrology and Topography

Dark faults Salm for apparently addressing only a single natural water source (St Mary’s Well) in his description of the area. Others to which Dark alludes apparently date from the fourth century and later Byzantine times (according to Dark’s footnote). Fair enough. Will keep this in mind when I have another look at Salm’s book. The point does not swing the argument either way over the existence of Nazareth in the early first century c.e., however.

As for topography, Dark does fault Salm’s generalization that “hill-slope locations preclude Roman period Jewish settlement”. The idea of a hill-slope settlement is important in order to match Luke’s account of the Nazareth villagers taking Jesus to a cliff top in order to toss him down to his death. Dark notes that hill-side settlements are known (elsewhere) in Galilee, and so are not theoretically impossible at the time of Jesus in the locale of Nazareth:

Structures on terraces and rock-cut hill-slope structures — recently discussed as a type of construction by Richardson — have been published from excavated Roman period Jewish settlements elsewhere in the Galilee . . . . Richardson’s book [2004] . . . might also have appeared too late for inclusion [in Salm’s bibliography].

The hillslopes in question are, according to Salm’s description, and not denied by Dark, “rocky, steep, and cavernous” and dotted with tombs, although the tombs apparently do not date prior to 50 c.e.

In contrast to the hillsides, the valley floor offers several advantages for the construction of dwellings: it is relatively flat, it is less rocky and has greater depth of soil, and it is not encumbered with caves, hollows, and pits. (Myth of Nazareth, p.220)

Against this, conformity to Luke’s account of the attempt to push Jesus off a cliff means that a settlement must be found in the adjacent hillsides.

Ken Dark’s critique would have had more punch had he addressed this point of Salm’s (the prima facie unlikeliness of a hillslope settlement in this particular place), and even moreso had he pointed to evidence for a pre-Christian settlement among the hillsides in question. Certainly the fact that the hillside tombs date from the latter part of the first century c.e. does not preclude the possibility of an earlier settlement beneath them. The evidence is still to be uncovered.

3. Dating the archaeological material — and dating publications

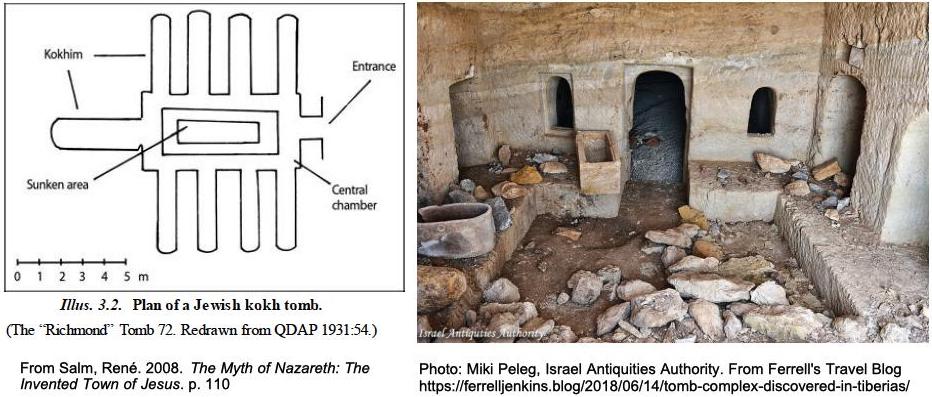

Ken Dark notes problems with Salm’s dating of the kokhim tombs, which, he writes, is “central to his thesis”:

the dating of these would have been more credible if he employed the dated typology in the now-standard work on Second Temple burial, Rachel Hachlili’s excellent 2005 book Jewish Funerary Customs, Practices and Rites in the Second Temple Period. This renders his chronology for tomb construction invalid, as it is based on interim, popular or outdated works, and leads him to ignore typological evidence for Hachlili’s Type 1 Second Temple period tombs in Nazareth.

Is it an over-reaction to see this criticism (failure to refer to a 2005 publication) as a little breathtaking when only a page earlier Dark had observed that a 2004 publication was probably too early to be referenced in Salm’s book? Are all scholarly reported dates prior to 2005 really rendered “invalid” by this 2005 publication?

Dark’s critique would, of course, be even more pertinent were it addressing evidence for village life, not death and burials.

Dark’s point that later tombs do not logically deny the possibility of evidence for village life existing below them in earlier strata is valid, nonetheless. Presumably, then, the implication is that the village Jesus knew would have been overlaid and/or dug up and used for tombs within some decades of the life of Jesus — although this implication is not explicitly raised, naturally enough.

4. Site of the Church of the Annunciation on tombs?

The suggestion [by Salm] that there were Roman period tombs . . . on the site of the present Church of the Annunciation is interesting, but the evidence is inconclusive.

Dark critiques aspects of Salm’s arguments for the church being built on what was primarily a tomb site, and that these preceded the agricultural activity at the site.

This is a point I’m prepared to continue to watch as others more knowledgeable debate. I am not clear on the centrality of this point, however, to the core of Salm’s case.

5. Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence

Ken Dark echoes a recent U.S. Secretary of “Defense” (sic):

Salm points to what he considers a lack of certain Late Hellenistic pottery from Nazareth . . . Before one can establish its absence from the record (and that is not, of course, the same as absence from the settlement) then one must set out what would, identifiably, constitute the presence of Late Hellenistic ceramics there.

What Dark means here is that sometimes a Jewish community chose not to use ceramics of a non-Jewish provenance.

These communities, therefore, eschewed the very wares, for example Eastern Terra Sigillata (‘ETS’), that may be most precisely dated or are most widely distributed elsewhere, such as Galilean Coarse Ware.

This is interesting, but Dark still frustratingly fails to address Salm’s key point here, the absence of evidence.

Few twenty-first-century archaeologists would credit Salm’s assertion that ‘two- and three-inch fragments of pottery vessels are a precarious basis indeed for fixing the type and date of an artefact’ (p.125).

Again, while Dark’s quotation draws attention to Salm’s amateur status, it simultaneously obscures from view the context and point Salm is making on page 125:

Because there is a non-correspondence between the diagrams and the descriptions [or Bagatti], however, we are in an impossible position.

Dark sidesteps the problem Salm is raising and that arises because the pottery shards are so fragmentary and few, and that they do not correspond to their verbal descriptions by Bagatti. How can we determine their real nature from such contradictory and scanty evidence alone?

Conclusion

I would have had more confidence in Dark’s portrayal of Salm as an ill-informed and illogical crank had he addressed in his review the core of Salm’s arguments.

I recommend reading Salm’s book with Dark’s review in hand for corrections and evaluations of various claims in The Myth of Nazareth, and to assess how at least one professional archaeologist responds to (or avoids) its central case.

I originally read René Salm’s dialogue with scholars, including archaeologists, on Crosstalk2 and nothing in Ken Dark’s review has persuaded me to dismiss out of hand Salm’s critiques of Nazareth archaeology. I remain open to all and any scholarly reports and discussions about the archaeological study of Nazareth. One summary of one set of these discussions is still available at message 13031.

As for the relevance of the study, I cannot go so far as to see the existence or non-existence of Nazareth in the early first century c.e. being central to “the survival of Christianity”. Astronomical and biological sciences have not undermined the faith. Archaeology won’t either. But if it can be established that Nazareth was not settled as a village until after the fall of Jerusalem, then there would be implications for dating the gospels.

Like this:

Like Loading...