Following is a recent assigmnment of mine — a research plan for an essay — that I think contains some information that will be of interest to some readers. . . . Russell Gmirkin gets a mention, by the way.

Rethinking Scribal Culture in Persian Period Yehud: Evidence and the Formation of the Hebrew Bible

Background, context, rationale

According to conventional scholarship, the Hebrew Bible took shape in Yehud, the Persian period province of Judah, with Samaria sometimes added as a contributing centre. This view rests largely on readings of Ezra–Nehemiah as historical sources and on frameworks inherited from the Documentary Hypothesis. Yet excavations show Yehud lacked the urbanization or resources necessary to sustain a scribal culture capable of producing such complex literature. A question rarely addressed is why there is very scant evidence of Hebrew writing in Yehud.1 By contrast, Iron Age II and the Late Hellenistic period yield abundant finds that “demonstrate widespread scribal activity and literacy across diverse media and inscriptional forms.”2 If Yehud was not the cradle of biblical literature, the implications are considerable, extending to the origins of Judaism’s foundational texts, the interpretation of writings that situate those origins in the Persian period, and conventional accounts of Judaism’s formation.

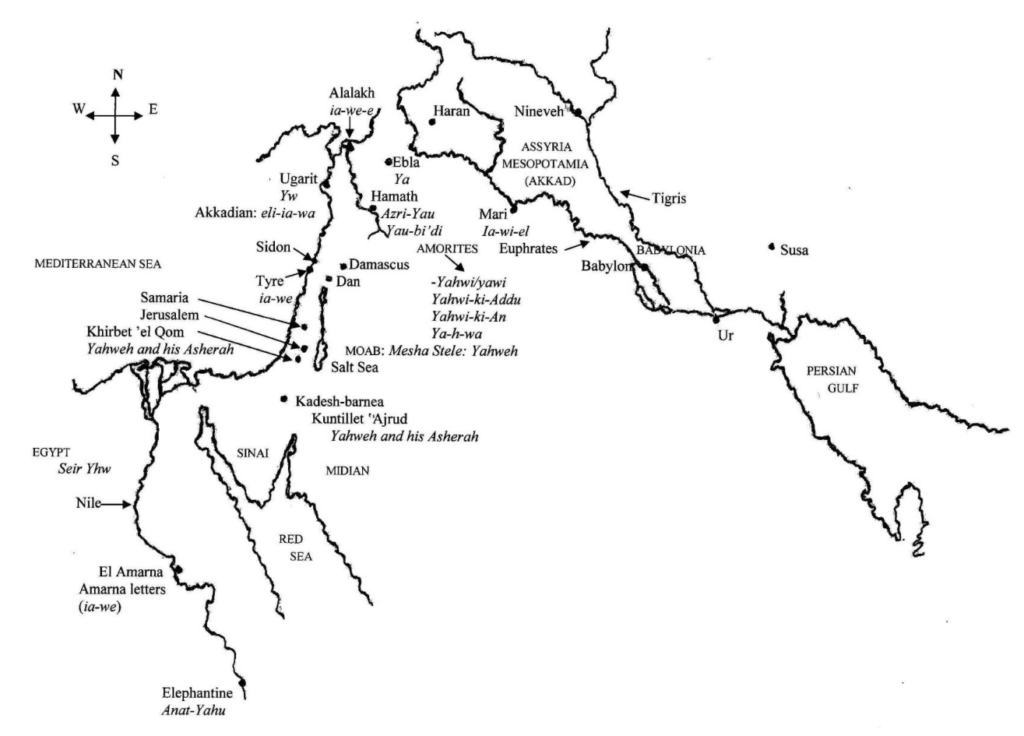

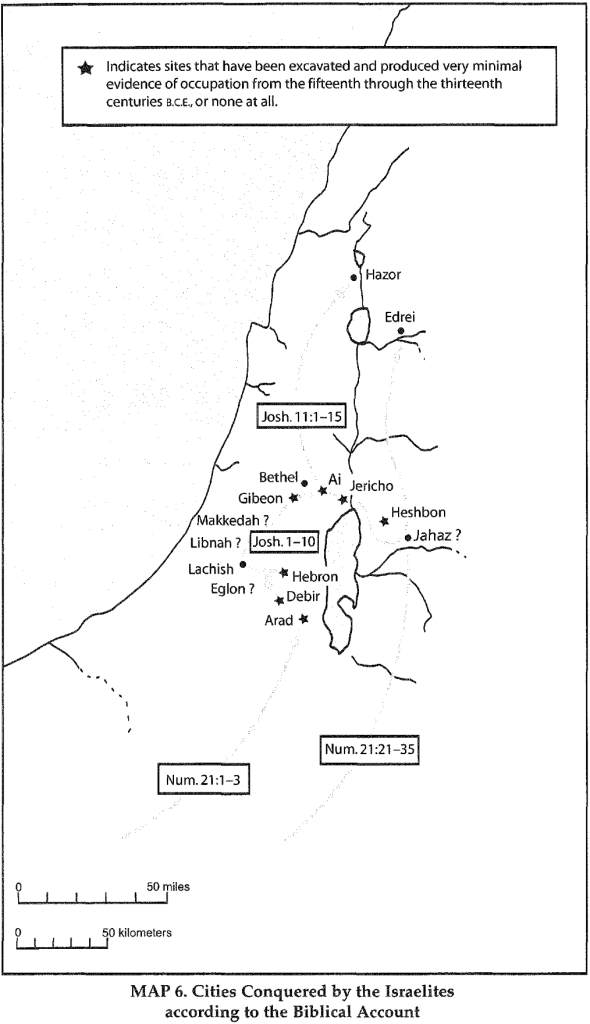

In 2016, Israel Finkelstein argued that archaeology does not corroborate the settings of Pentateuchal narratives but rather can only illuminate the contexts of their composition.3 At the 2022 Yahwism under the Achaemenid Empire conference he updated4 that publication with reference to new excavations and the Tel Aviv University digital epigraphy project.5 He advised looking for the origins of the Biblical literature in the Iron Age and then in Babylonia (as more recently suggested by Albertz6 and Römer7) or Egypt – with additions as late as the Hasmonean era. Taken together, the material record points away from fifth and fourth century Palestine for the production of the biblical literature.

Finkelstein’s challenge has yet to gain traction in mainstream scholarship. At the same conference, only Reinhard G. Kratz explicitly addressed the tension between the archaeological record and the assumption that biblical literature was taking shape in Yehud, highlighting the disparity between the forms of “Judaism” attested in the epigraphic sources of Yehud and those presupposed in the biblical tradition.8

An even more radical challenge comes from Yonatan Adler’s 2022 study of archaeological evidence, which establishes that Judeans continued a polytheistic Yahwism and show no awareness of Torah observance before the third century.9

The 2019 volume On Dating Biblical Texts to the Persian Period sought firmer criteria for fifth-century dating.10 Its essays reflect the general trends in the study of the Hebrew Bible’s origins – relying almost entirely on textual analysis, with archaeology relegated to a secondary role, if acknowledged at all. When an attempt is made to apply a theoretical historical method, as when Konrad Schmid invokes Ernst Troeltsch’s principles, the task fails because, as is so common, historicity of the texts is presupposed, thus falling into circular reasoning.11 Again reflecting common procedures in the wider field, other contributions date texts linguistically to the Achaemenid period, a contested procedure.12

Kratz has elsewhere sought to maintain the fifth and fourth centuries as the formative period for the biblical texts by suggesting that the traditions circulated orally at this time and crystallized into written texts only in the Hellenistic age.13 The papyri from the fifth century colony at Elephantine testify to a form of Yahwism with little resemblance to Pentateuchal prescriptions, despite scholarly efforts to detect in them some background awareness of biblical writings, as Kratz observes. Further, these and other Aramaic papyri from Samaria show no signs of the scribal activity that would have been necessary for the production of biblical literature.

Archaeology further indicates a markedly low population in Persian period Yehud compared with the Iron Age and Hellenistic eras—too low, some argue, to sustain centers of scribal culture.

Niels Peter Lemche has challenged the mainstream by emphasizing the circularity of arguments for a Persian period origin of biblical literature, stressing that archaeological surveys of the period render such a dating highly improbable.14 He argues that the Hellenistic period provides the most plausible setting for the creation of these texts. In recent years, a small but growing number of scholars15 have argued for strong textual relationships between the Hebrew texts and Greek literature—relationships that suggest not merely indirect influence through Achaemenid era trade contacts but to a deeper engagement with Hellenistic intellectual culture that contributed to the formation of the Hebrew Bible.

Aims and objectives

1: Clarify the scholarly consensus on the nature of the biblical literature.

Survey how scholarship generally characterizes the Hebrew Bible as a composite work shaped by multiple sources, successive redactions, and editorial layers. Establish what kind of scribal activity this consensus presupposes, and use it as the baseline for testing whether Achaemenid Palestine could plausibly support such production.

2: Assess expected forms of writing and scribal activity.

Distinguish functional writing (administrative, economic, and legal records) from evidence for sustained literary scribal culture (e.g. physical space for archives and schools, inscriptions). Specify what types of finds would be expected if a scribal society capable of producing complex literature were present.

3: Contextualize Persian period material finds within broader patterns of settlement and urbanization.

Identify the archaeological record of Persian period Palestine, comparing it with that of Iron Age II and the Late Hellenistic period. Highlight demographic and urbanization changes in key regions (Jerusalem, Bethel, Samaria, Mount Gerizim), and assess whether these shifts plausibly indicate conditions supportive of a scribal-literary culture.

4: Identify and analyze Persian period finds.

Present the relevant finds from Yehud (Jerusalem and Bethel), Samaria (Shechem and Wadi Daliyeh) and related sites. These will be described with respect to:

- medium (stone, clay, papyrus, coins, seals, bullae, ostraca),

- archaeological context (urban, rural, temple, cave, or administrative building),

- language and script (Aramaic or Hebrew),

- function and audience (who produced the text, for whom, and for what purpose).

5: Assess external and imperial evidence and arguments advanced in support of a Persian period creation of biblical literature.

Examine evidence outside Palestine that bears on the question of Pentateuchal origins, including the Elephantine papyri, the evidence for the supposed decree of Darius I to codify laws, and other fifth and fourth century literary sources (e.g. Herodotus, Theophrastus). Assess the debates over whether the external archaeological evidence corroborates or challenges the idea of a necessary scribal milieu.

6: Review other common arguments for Persian period authorship.

Survey the evidence and assumptions underlying widespread arguments that biblical literature essentially came together in Persian-ruled Palestine, and evaluate critical responses in the scholarship. Particular attention to be given to:

- linguistic variations in the Pentateuch and their chronological implications,

- narratives of Ezra and Nehemiah as historical witnesses to fifth century events.

7: Explore alternative explanations for the provenance of the Hebrew Bible.

Identify alternative models for the origins of the Hebrew Bible and assess their viability (e.g., Hellenistic-period composition or layered traditions). Consider why biblical narratives themselves point to the time of Persian domination as formative for Judaism, and whether this reflects memory, ideology, or literary construction rather than historical fact. This will lay the groundwork for exploring models of provenance beyond the Persian period hypothesis.

Research methods, techniques, and tools

Scholarly foundations and theoretical approach

The research will begin with the most recent collective examination of Persian-period Palestine: the Yahwism under the Achaemenid Empire conference (December 2022; published 2024). Of particular significance is Israel Finkelstein’s paper, which argues from archaeological evidence against the prevailing view that the Persian period was decisive for the emergence of biblical literature.16

Primary evidence—data from the time and place under investigation—will be assessed independently, rather than interpreted through biblical texts, unless those texts can be shown to convey information that has been transmitted reliably from direct interaction with the event. Archaeological finds will be treated on their own terms, not used to confirm religious or ideological17 narratives. This approach, sometimes criticized as “hyper-critical,” is instead an effort to respect the integrity of different sources: material data as direct evidence of their period, and literary texts as works requiring literary analysis before being considered evidence for historical events.18 As several scholars have long observed19 the Persian period construct of the biblical literature is based on circular argumentation—assuming underlying historicity of biblical narratives and interpreting archaeological finds through those narratives to confirm the basic narrative construct

Archaeological and epigraphic data

The study will consult the major published corpora and excavation reports relevant to Persian period Palestine. These include standard print publications20 as well as specialized online databases to check for more recent finds. Of particular importance are:

Bibliographic research

Online and hard copy scholarly sources from diverse perspectives will be assessed for both the nature of the archaeological finds and the various interpretations of these finds. See the Annotated Bibliography.

Translation tools

Because much of the relevant scholarship is published in German, French, and Hebrew, among other languages, digitization and translation tools (including ABBYY Finereader and AI-translation programs) will be employed to ensure access to non-English work.

Scope

The focus will be on Persian administered Yehud and Samaria. Other areas and periods will be referenced only for summary comparison and analytical purposes. Conventional scholarly views of the biblical literature will be used for comparison; no separate literary analysis will be undertaken. Alternative hypotheses will be briefly noted.

Notes

1 Finkelstein, Jerusalem the Center of the Universe, 351.

2 Finkelstein, “Jerusalem and Judah 600–200 BCE Implications for Understanding Pentateuchal Texts,” 14.

3 Finkelstein, 3.

4 Finkelstein, “Archaeology’s Black Hole: Jerusalem and Yehud/Judea in the Persian and Early Hellenistic Periods.”

5 Faigenbaum-Golovin et al., “Literacy in Judah and Israel.”

6 Albertz, Israel in Exile.

7 Römer, “Comment Dater Les Textes Du Pentateuque ? Quelques cas d’étude”; Römer, The So-Called Deuteronomistic History.

8 Kratz, “Where to Put ‘Biblical’ Yahwism in Achaemenid Times?”

9 Adler, The Origins of Judaism.

10 Bautch and Lackowski, On Dating Biblical Texts to the Persian Period.

11 Schmid, “How to Identify a Persian Period Text in the Pentateuch.”

12 Ehrensvärd, “Why Biblical Texts Cannot Be Dated Linguistically”; Hurvitz, “The Recent Debate on Late Biblical Hebrew”; Young, “Starting at the Beginning with Archaic Biblical Hebrew.”

13 Kratz, “Temple and Torah: Reflections on the Legal Status of the Pentateuch between Elephantine and Qumran”; Kratz, Historical and Biblical Israel.

14 Lemche, “The Old Testament—A Hellenistic Book?”

15 Thompson and Wajdenbaum, The Bible and Hellenism; Gmirkin, Plato’s Timaeus and the Biblical Creation Accounts; Gmirkin, Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible; Gmirkin,Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus; Wajdenbaum, Argonauts of the Desert: Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible; Wesselius, Origin of the History of Israel.

16 Finkelstein, “Archaeology’s Black Hole: Jerusalem and Yehud/Judea in the Persian and Early Hellenistic Periods.” Even Finkelstein, who warns against such circularity in his paper, himself falls into the same trap when interpreting Iron Age Judah as the time of a literary renaissance and the composition of the Book of Deuteronomy (Silberman and Finkelstein, The Bible Unearthed).

17 El-Haj, Facts on the Ground, 8.

18 Eckhardt, “Memories of Persian Rule: Constructing History and Ideology in Hasmonean Judea,” 262; Finley, Ancient History, 12f, 21; Kosso, “Observation of the Past,” 30ff; Liverani,Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography, 28; Moles, “Truth and Untruth in Herodotus and Thucydides,” 90, 115, 120; Woodman, “From Hannibal to Hitler: The Literature of War,” 120.

19 Lemche, The Old Testament Between Theology and History: A Critical Survey; Lemche, Early Israel: Anthropological and Historical Studies on the Israelite Society Before the Monarchy; Thompson, Early History of the Israelite People; Davies, In Search of “Ancient Israel.” Despite such criticisms the scholarly field has for most part resisted a method that fully gives primacy to archaeology. A large segment of scholars adopts a “centralist” position, one that is in between accepting the Bible to be true until proven otherwise and those who avoid a priori presumption of historical reliability in the Hebrew Bible (Lemche, Ancient Israel, pp 5-9).

20 Magen, Misgav, and Tsfania, Mount Gerizim Excavations. Volume I; Dušek, Les manuscrits araméens du Wadi Daliyeh et la Samarie vers 450–332 av. J.-C.; Stern, Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, Volume II; Porten, The Elephantine Papyri in English.

Bibliography

Adler, Yonatan. The Origins of Judaism: An Archaeological-Historical Reappraisal. In The Origins of Judaism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2022.

Albertz, Rainer. Israel in Exile: The History and Literature of the Sixth Century B.C.E. Studies in Biblical Literature, no. 3. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 2003.

Bautch, Richard J., and Mark Lackowski, eds. On Dating Biblical Texts to the Persian Period: Discerning Criteria and Establishing Epochs. Forschungen Zum Alten Testament. 2. Reihe, 101. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2019.

Dušek, Jan. Les manuscrits araméens du Wadi Daliyeh et la Samarie vers 450–332 av. J.-C. Leiden ; Boston: Brill, 2007.

Eckhardt, Benedikt. “Memories of Persian Rule: Constructing History and Ideology in Hasmonean Judea.” In Persianism in Antiquity, edited by Rolf Strootman and Miguel John Versluys, 249–65. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2017.

Ehrensvärd, Martin. “Why Biblical Texts Cannot Be Dated Linguistically.” Hebrew Studies 47 (2006): 177–89.

El-Haj, Nadia Abu. Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-Fashioning in Israeli Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Faigenbaum-Golovin, Shira, Arie Shaus, Barak Sober, Yana Gerber, Eli Turkel, Eli Piasetzky, and Israel Finkelstein. “Literacy in Judah and Israel: Algorithmic and Forensic Examination of the Arad and Samaria Ostraca.” Near Eastern Archaeology 84, no. 2 (June 2021): 148–58.

Finkelstein, Israel. “Archaeology’s Black Hole: Jerusalem and Yehud/Judea in the Persian and Early Hellenistic Periods.” Paper presented at Yahwism under the Achaemenid empire (Prof. Shaul Shaked in memoriam), University of Haifa. December 21, 2022. Video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8T21U7tBCB8.

———. “Jerusalem and Judah 600–200 BCE Implications for Understanding Pentateuchal Texts.” In The Fall of Jerusalem and the Rise of the Torah, edited by Dominik Markl, Jean-Pierre Sonnet, and Peter Dubovsk, 3–18. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2016.

———. Jerusalem the Center of the Universe: Its Archaeology and History (1800–100 BCE). Atlanta: SBL Press, 2024.

Finley, M. I. Ancient History: Evidence and Models. New York: Viking, 1986.

Gmirkin, Russell E. Berossus and Genesis, Manetho and Exodus: Hellenistic Histories and the Date of the Pentateuch. New York: T&T Clark, 2006.

———. Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible. New York: Routledge, 2016.

———. Plato’s Timaeus and the Biblical Creation Accounts: Cosmic Monotheism and Terrestrial Polytheism in the Primordial History. Abingdon, Oxon.: Routledge, 2022.

Hurvitz, Avi. “The Recent Debate on Late Biblical Hebrew: Solid Data, Experts’ Opinions, and Inconclusive Arguments.” Hebrew Studies 47 (2006): 191–210.

Kosso, Peter. “Observation of the Past.” History and Theory 31, no. 1 (February 1992): 21.

Kratz, Reinhard G. Historical and Biblical Israel: The History, Tradition, and Archives of Israel and Judah. Translated by Paul Michael Kurtz. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

———. “Temple and Torah: Reflections on the Legal Status of the Pentateuch between Elephantine and Qumran.” In The Pentateuch as Torah: New Models for Understanding Its Promulgation and Acceptance, edited by Gary N. Knoppers and Bernard M. Levinson, 77–103. Winona Lake, Ind: Eisenbrauns, 2007.

———. “Where to Put ‘Biblical’ Yahwism in Achaemenid Times?” In Yahwism Under the Achaemenid Empire: Professor Shaul Shaked in Memoriam, edited by Gad Barnea and Reinhard G. Kratz, 267–68. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2024.

Lemche, Niels Peter. Ancient Israel: A New History of Israel. 2nd edition. London: T&T Clark, 2015.

———. “The Old Testament—A Hellenistic Book?” In Did Moses Speak Attic? Jewish Historiography and Scripture in the Hellenistic Period, edited by Lester L. Grabbe, 287–318. Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 2001.

Liverani, Mario. Myth and Politics in Ancient Near Eastern Historiography. Translated by Zainab Bahrani and Marc Van De Mieroop. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2007.

Magen, Yitzhak, Haggai Misgav, and Levana Tsfania. Mount Gerizim Excavations. Volume I: The Aramaic, Hebrew and Samaritan Inscriptions. Translated by Edward Levin and Michael Guggenheimer. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, 2004.

Moles, J. L. “Truth and Untruth in Herodotus and Thucydides.” In Lies and Fiction in the Ancient World, edited by Christopher Gill and Timothy Peter Wiseman, 88–121. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 1993.

Porten, Bezalel. The Elephantine Papyri in English: Three Millennia of Cross-Cultural Continuity and Change. Leiden: Brill, 1996.

Römer, Thomas. “Comment dater les textes du Pentateuque? Quelques cas d’étude.” In Finkelstein and Römer, Aux origines de la Torah: Nouvelles rencontres, nouvelles perspectives, chap. 2. Montrouge Cedex (France): Bayard, 2019.

———. The So-Called Deuteronomistic History: A Sociological, Historical and Literary Introduction. London ; New York: T&T Clark, 2007.

Schmid, Konrad. “How to Identify a Persian Period Text in the Pentateuch.” In On Dating Biblical Texts to the Persian Period: Discerning Criteria and Establishing Epochs, edited by Richard J. Bautch and Mark Lackowski, 101–18. Forschungen Zum Alten Testament. 2. Reihe, 101. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2019.

Silberman, Neil Asher, and Israel Finkelstein. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York: Touchstone, 2002.

Stern, Ephraim. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible, Volume II: The Assyrian, Babylonian, and Persian Periods. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 2001.

Thompson, Thomas L., and Philippe Wajdenbaum, eds. The Bible and Hellenism: Greek Influence on Jewish and Early Christian Literature. Durham: Routledge, 2014.

Wajdenbaum, Philippe. Argonauts of the Desert: Structural Analysis of the Hebrew Bible. London: Equinox, 2011.

Wesselius, Jan-Wim. Origin of the History of Israel: Herodotus’ Histories as Blueprint for the First Books of the Bible. London: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002.

Woodman, A. J. “From Hannibal to Hitler: The Literature of War.” The University of Leeds Review 26 (1983): 107–24.

Young, Ian. “Starting at the Beginning with Archaic Biblical Hebrew.” Hebrew Studies 58 (2017): 99–118.

Like this:

Like Loading...