I intend in this post to throw an idea into the ring for consideration. I have very little with which to defend the idea but I find it of interest. I have nothing stronger than that as my motive for posting it here:

that the serpent in the Garden of Eden was an allusion to the seduction of Greek wisdom

Early last year I posted — solely for the purpose of showing that the idea was not unknown among scholars — a summary of one academic proposal that Plato at one point was ultimately drawing upon the biblical Garden of Eden story of “the fall”. I still have strong reservations about the case made in that article and for that reason I have from time to time returned to have another look at the relevant sources to see if more cogent sense can be made of the comparisons or if the notion should be dropped entirely. Now I would like to propose a more plausible and cogent case for the reverse: that the biblical authors were drawing upon Plato. (The idea that the Hebrew Bible drew upon Greek literature is a minority view among scholars but nonetheless a reputable one that has been published in academic sources: see Niels Peter Lemche, Mandell and Freedman, Jan-Wim Wessellius, Philippe Wajdenbaum, Russell Gmirkin, and related posts etc)

The Ambiguity of the Serpent: Greek versus Biblical

It is impressive to note how ophidian or anguine symbolism permeates Greek and Roman legends and myths, shaping Hellenistic culture. (Charlesworth, 127)

Yes, the serpent was a positive image among the Greeks of the classical and hellenistic eras of their chief god Zeus, but I will offer a more specific literary connection.

Evangelia Dafni attempted to argue that Plato’s panegyric of Socrates was indebted to some extent to the serpent who tempted Eve (see first link above). A key weakness in the argument, I believe, was its failure to provide a clear motive for the borrowing. If there was borrowing from the Hebrews it seemed to fail to add anything extra to the understanding of Plato’s text.

But notice how different everything looks in reverse. A potentially new depth of meaning is indeed added to the Genesis narrative by inverting Dafni’s suggestion.

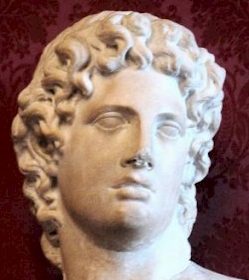

Socrates can justly be considered the paragon of Greek wisdom. One might say that Socrates was the midwife at the birth of Greek philosophy, epitomized by Plato and Aristotle and their offshoots. In his dialogue The Symposium Socrates is directly compared with a viper whose bite is compared with Socrates overpowering his interlocutor by his unassailable questioning and speech. Socrates is depicted as being in a class of his own above all other mortals because of his wisdom as Eden’s serpent is wise above all the beasts of the earth. Socrates offers the wisdom of the gods. If one who had not met Socrates felt no disgrace or shame about his person, after an encounter with Socrates he would indeed be overwhelmed with shame of his former state of ignorance — as Adam and Eve were not ashamed of their nakedness until after they succumbed to the serpent’s temptation. What Socrates offers with his words is described as full of beauty, desirability and wisdom.

At this point, let’s recall the passage in Genesis:

2:25 And the two were naked, both Adam and his wife, and were not ashamed.

3:1 Now the serpent was more φρονιμώτατος [LXX = discerning, prudent, wise] than any of the wild animals the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, “Did God really say, ‘You must not eat from any tree in the garden’?”

2 The woman said to the serpent, “We may eat fruit from the trees in the garden, 3 but God did say, ‘You must not eat fruit from the tree that is in the middle of the garden, and you must not touch it, or you will die.’”

4 “You will not certainly die,” the serpent said to the woman. 5 “For God knows that when you eat from it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.”

6 When the woman saw that the fruit of the tree was good for food and pleasing to the eye, and also desirable for gaining wisdom, she took some and ate it. She also gave some to her husband, who was with her, and he ate it. 7 Then the eyes of both of them were opened, and they realized they were naked; so they sewed fig leaves together and made coverings for themselves.

Let’s back up a little and start at the beginning.

Socrates is telling his companions a story of his encounter with the prophetess Diotima of Mantineia (punning names that could be translated literally as “Fear-God of Prophet-ville” – Rouse, 97) who educated him about the nature of love and immortality. Interestingly (perhaps, for me at any rate) Socrates deems the act of sexual intercourse between a man and woman as generating a form of immortality:

“To the mortal creature, generation is a sort of eternity and immortality,” she replied; “and . . . . we needs must yearn for immortality no less than for good . . . .”

All this she taught me at various times . . . . (Symposium, 206e-207a)

The discussion extends to addressing various ways humans can be thought of as immortal (“continually becoming a new person”), not unlike (this is my own comparison here, not that of Socrates) the common ancient image (as ancient as the epic of Gilgamesh) of the serpent regularly shedding its old skin in a process of “eternal” renewal.

I was astonished at her words, and said: “Is this really true, O thou wise Diotima?”

And she answered with all the authority of an accomplished sophist: “Of that, Socrates, you may be assured; — think only of the ambition of men, and you will wonder at the senselessness of their ways, unless you consider how they are stirred by the love of an immortality of fame. They are ready to . . . undergo any sort of toil, and even to die, for the sake of leaving behind them a name which shall be eternal. (208c)

Socrates proceeds to report Diotima’s elucidation of what is truly beautiful, “passing from view to view of beautiful things” until the one learning wisdom finally grasps true beauty and no longer is content with the inferior beauty of the physical world. Diotima concludes:

“Do consider,” she said, “beholding beauty with the eye of the mind, [one] will be enabled to bring forth, not images of beauty, but realities . . . and bringing forth and nourishing true virtue to become the friend of God and be immortal, if any man ever is.” (212a)

After Socrates’ speech in which the words of a divinely inspired prophet were presenting the ultimate in beauty that could ever be desired by mortals for the sake of an immortal name, who should rudely interrupt the occasion but a drunken Alcibiades. Alcibiades was a “man of the world”, a famed political figure, conscious of his beauty but also one who was enamoured of Socrates, both intellectually and physically.

In Plato’s dialogue each guest had been expected to deliver some kind of ode to “love”. Alcibiades, arriving late, instead will tell all what Socrates himself can be likened to — in similes. Socrates is like the ugly Silenus, grotesque on the outside but cut him open and inside you will find images of the gods. Or he is like the entrancing satyr Marsyas who invented the music of the flute and “bewitched men by the power of his mouth”. The only difference, Alcibiades explains, is that Socrates can enchant and stir a longing for the divine merely by the means of his speech:

The only difference … is that you [=Socrates] do the very same without instruments by bare words! . . .

When one hears you . . . we are overwhelmed and entranced. (215c-d)

Alcibiades brings in another simile with which to liken Socrates and his words: the serpent, specifically the persuasive power of the serpent!

Besides, I share the plight of the man who was bitten by the snake. . . . I have been bitten by a more painful viper, and in the most painful spot where one could be bitten — the heart, or soul, or whatever it should be called — stung and bitten by his discourses in philosophy, which hang on more cruelly than a viper when they seize on a young and not ungifted soul, and make it do and say whatever they will. (217e-218a)

Eve is not bitten by the serpent, of course, but she and Adam do for the first time feel shame as a consequence of listening to him. Shame was the bite Alcibiades said he felt after his time with Socrates. Alcibiades had attempted to seduce Socrates sexually but found him unmoved. Socrates gently chastised him by pointing out that he was trying to exchange what was beautiful to one’s physical eyes and pleasures (bronze) for the true beauty of wisdom (gold) – with the result that Alcibiades felt deep shame for his attempts to attain sexual favour with Socrates:

And there is one experience I have in presence of this man alone, such as nobody would expect in me; and that is, to be made to feel ashamed [αἰσχύνομαι, a form of the same word in LXX Gen 2:25]; he alone can make me feel it. . . I cannot contradict him . . . and, whenever I see him, I am ashamed . . . . (216b-c)

It is at that point where Alcibiades begins to describe his vain attempt to seduce Socrates and its humiliating aftermath.

Socrates was a man like no other:

There are many more quite wonderful things that one could find to praise in Socrates: but . . . it is his not being like any other man in the world, ancient or modern, that is worthy of all wonder. . . .

When you agree to listen to the talk of Socrates . . . you will find his words first full of sense, as no others are . . . (221c-222a)

But, Alcibiades warns, beware of being seduced by his wisdom to the extent that you are stirred to a desire for sexual gratification (an exchange of false beauty for true) and one feel shame as a consequence:

That is a warning to you . . . not to be deceived by this man . . . . (222b)

There we have it. In one episode in Plato’s dialogues we have a blend of a person “more wise” than any other mortal, one likened to a serpent, one whose speech is overpoweringly persuasive, who promises a form of immortality, who displays all that is truly beautiful and to be desired, yet who leaves the ignorant feeling shame over their former condition — specifically in relation to sexual desire.

Much more could be written but I have introduced them in earlier posts. We have seen Russell Gmirkin’s observation that it was Plato who portrayed an idyllic origin scene where animals and humans could converse with one another. I linked above to a similar discussion by Evangelia Dafni who drew attention to Plato’s comparison of Socrates with the serpent — although I believe this post brings an explanation for a possible borrowing from Plato to the Bible. If we ride with the possibility of a Hellenistic origin for the biblical literature, we may see in the serpent’s temptation of Adam and Eve a rebuke to the Greek philosophy that would have stood opposed to the wisdom that must come from an obedience to the commands of God. The image of the serpent as a religious icon had been familiar enough in the Levant for millennia and was most prominent anew in the Hellenistic world with its associations with Zeus, Athena and a host of other Greek associations (compare, for example, the golden fleece in a tree guarded by a serpent) — and even as a fit simile for the shame-inducing yet enlightening and immortality promising wisdom of Socrates.

By no means do I expect the above thoughts to seduce an innocent to partake of the wisdom of a Hellenistic origin of the Hebrew Bible. I present the above thoughts as an observation of some interest to those already persuaded on other grounds for the stories of Genesis being being formed from the raw material of Greek literature, Plato in particular.

Charlesworth, James H. The Good and Evil Serpent: How a Universal Symbol Became Christianized. New Haven Conn.: Yale University Press, 2010.

Dafni, Evangelia G. “Genesis 2–3 and Alcibiades’s Speech in Plato’s Symposium: A Cultural Critical Reading.” HTS Teologiese Studies 71, no. 1 (2015).

Rouse, W. H. D. Great Dialogues of Plato – The Republic – Apology – Crito – Phaedo – Ion – Meno – Symposium. Mentor Books, 1956.

Translations of Plato are a mix of those by Jowett, Fowler and Rouse (above) — with constant reference to the Greek text at the Perseus Digital Library