Continuing from Why Josiah’s Reforms “Must Have Happened” – part 2

The Deuteronomistic History (DH) is a modern theoretical construct holding that behind the present forms of the books of Deuteronomy and Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings (the Former Prophets in the Hebrew canon) there was a single literary work. In the late 19th century, some scholars conceived of the DH as a loosely edited collection of works, written in reference to some of the standards espoused in the book of Deuteronomy. Oxford Bibliographies

Rainer Albertz is disputing the arguments of Philip R. Davies that the book of Deuteronomy and the Deuteronomistic History could not have been written as early as the time of King Josiah. Part 2 addressed Deuteronomy itself; part 3 looks at the dating of the Deuteronomistic History.

We saw in Part 1 that Finkelstein and Silberman defaulted to the view that Josiah’s reforms had to have been historical despite the lack of unambiguous archaeological evidence. Albertz points out that there is wide acceptance of this view:

The suggestion that the report of Josiah’s reform was contemporary with the events, which is advocated by most scholars of the Cross school, has led I. Finkelstein and N.A. Silberman, among others, to believe that the DtrH is completely reliable on this point. (37)

What is the Cross school? It is the viewpoint aligning with much of the work of Frank Moore Cross, in particular beginning with Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic. There we read:

What is the Cross school? It is the viewpoint aligning with much of the work of Frank Moore Cross, in particular beginning with Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic. There we read:

We are pressed to the conclusion by these data that there were two editions of the Deuteronomistic history, one written in the era of Josiah as a programmatic document of his reform and of his revival of the Davidic state. In this edition the themes of judgment and hope interact to provide a powerful motivation both for the return to the austere and jealous god of old Israel, and for the reunion of the alienated half kingdoms of Israel and Judah under the aegis of Josiah. The second edition, completed about 550 B.C., not only updated the history by adding a chronicle of events subsequent to Josiah’s reign, it also attempted to transform the work into a sermon on history addressed to Judaean exiles. (Cross, 287)

As we saw in Part 1, that was exactly the view F&S were following.

But Cross is not given the last word when it comes to the date of the Deuteronomistic History in which the narrative of Josiah and the discovery of the scroll of the Law is found.

But recently Th. Römer, who sympathizes with the Cross school, has shown convincingly that 2 Kings 22-23 ‘should be dated from the exilic period’ (Römer 1997: 10). (37)

Römer lays out a fascinating list of episodes that reflect the literary trope we find in the account of the discovery of the book of Deuteronomy in 2 Kings. Some extracts from Römer’s article:

There may be quite a consensus in critical scholarship about the seventh Century B.C.E. as the starting point of deuteronomism. . . . (2)

Scholars have often used II Reg 22 to reconstruct the »historical circumstances« of the Josianic reform. But a positivist historical reading of the book-finding event does not help much to understand the text. Speyer has demonstrated that the [motif] of book findings in temples or holy places is a quite common literary motive in Antiquity which is mostly used »um einem gerade angefertigten Werk den Schein höheren Alters und großer Heiligkeit zu verleihen« [=”in order to give a newly created work the appearance of greater age and great holiness”]. . . .

The discovery-reports are often variations of the following diagram:

1. An important person wants to change or to »restore« important features in society.

2. He is afraid of Opposition.

3. He or one of his loyal servants is sent to a holy place.

4. There he discovers a Book or written oracles which are of divine origin.

5. This discovery gives divine impulse to the projects of the hero. (7f – my list formatting)

[I]t is clear that the authors or redactors of II Reg 22—23 resort to the same literary convention . . . . (9)

46Cf. for instance M. Rose, Der Ausschließlichkeitsanspruch Jahwes. Deuteronomistische Schultheologie und die Volksfrömmigkeit der späten Königszeit, BWANT 106, 1975. Even if Rose brings too far his Interpretation of the archeological data, it is quite clear that the kingdom of Judah became important only in the Vllth Century B.C.E. — 106 may be a typo: see pp 157ff

If II Reg 22—23 is to be read as the foundation myth of the dtr. group and as an ideological or theological attempt to have the end of monarchy accepted, then this text can hardly be used for a reconstruction of the historical circumstances, of the so-called Josianic reform. We should follow scholars like Würthwein, Davies and others and consider II Reg 22—23 above all as a literary and theological construct. This does not mean that no »reform« under Josiah ever existed, we may have even some archaeological support for it46, but it is methodological circularity to claim that such a recognization [sic] of politics and cultic affairs under Josiah has been caused by the »discovery« of Deuteronomy. It may also be still possible to reconstruct a Josianic Urdeuteronomium, even if there is no consensus about this reconstruction in recent attempts. II Reg 22—23 should be dated from the exilic period. (10)

So we return to where we began — with Philip Davies’ pointing out the circularity of using the 2 Kings account of the discovery of the book of Deuteronomy to date the book of Deuteronomy and verify the historicity of Josiah’s reforms. Further, the entire narrative should rather be dated from the exilic period, the time of the Babylonian exile, Albertz concurs. (Of course, I am proposing that it could be dated even later — to the Hellenistic period. The point here is that there is no immovable anchor that binds the origin of the narrative to the seventh century.)

The Deuteronomistic History concludes with the deported king of Judah being shown mercy in Babylon and restored to a comfortable life in the royal court. 2 Kings 25:27-30

27 In the thirty-seventh year of the exile of Jehoiachin king of Judah, in the year Awel-Marduk became king of Babylon, he released Jehoiachin king of Judah from prison. He did this on the twenty-seventh day of the twelfth month. 28 He spoke kindly to him and gave him a seat of honor higher than those of the other kings who were with him in Babylon. 29 So Jehoiachin put aside his prison clothes and for the rest of his life ate regularly at the king’s table. 30 Day by day the king gave Jehoiachin a regular allowance as long as he lived.

Römer further observes that that conclusion to the Deuteronomistic History

shares literary conventions with the stories of Esther and Joseph which Meinhold called »novels of the diaspora«. Yoyakin’s fate is similar to that of Mardochai and Joseph. In all three cases an exiled person among others becomes second to the king (II Reg 25,28; Est 10,3; Gen 41,40), and the accession to this new status is symbolized by changing clothes (II Reg 25,29; Est 6,10-11; 8,15; Gen 41,42). These accession stories transform exile into diaspora. The land of deportation changes into a land where the foreigner is welcome. One can live very well outside eretz yisrael and manage interesting careers. It is then not so astonishing that the »hope for return« is quite discreet in the DH. It is enough to know how to pray towards the temple (I Reg 8,48).

Why, then, do we not see any hints of a Persian period in the text if it was really written during that time?

51 See for a similar literary strategy the end of Luke’s Acts, and on this topic, P. Davies, Expository Times 94 (1983), 334-335. — To add to R’s footnote: What a rewarding surprise to find the same view I proposed in a 2007 post. But I cannot deny Davies noticed it first.

We may still ask why are there no direct allusions to the Persian period in DH. Probably because the Dtrs. of the postexilic times were quite »modern« historians: if you write a historiography you do not include your own present51.

The question then becomes, “Is it possible to define a latest possible date” for the composition of the Deuteronomistic History?

To answer this question Albertz notes that in every reference to the exile in the Deuteronomistic History (as in Solomon’s prayer and the conclusion of 2 Kings) there is no hint that the author is aware that the Babylonian exile will come to an end. There is no hint of awareness that the Babylonian empire will fall.

In other prophetic works — Jeremiah 29:10-14 and Isaiah 40:1-2 — Albertz points out that the authors foresaw the collapse of the Babylonian empire with the advancing power of the Persians. He finds other references to the return from exile (Deuteronomy 4:29-31, 30:1-11, Jeremiah 31:31-33; 32:37-41; etc — being written from the perspective of early days in the return from exile.

In the event that the DtrH emerged largely between 562 and 547 and its later parts followed until the year 520, then several conclusions can be drawn which are of some importance for the assessment of the Josianic reform. First, we get another important confirmation that the book of Deuteronomy could not have emerged in the later Persian period but must have been written earlier. Since Deuteronomy 4 presupposes not only the Deuteronomic core in chs. 12-26 [in Part 2 we saw how Albertz dated this work to Josiah’s time], but also includes its admonitory frame in Deut. 4.44-30.20, the book of Deuteronomy must have been largely finished by 540. Second, since most of the DtrH was composed during the 15 years following the release of Jehoiachin (562), their authors were not too far away from the period when Josiah’s reform was carried through (622-609 BCE).

they could not invent . . . . they could not lie

This brings us to what I call might call a “classic” argument so often used in attempting to date biblical narratives close to the time of the events they describe:

This would mean that the Deuteronomistic Historians had to be aware that there were still some eye-witnesses alive and that there were a lot of people among their audience whose fathers or grandfathers had participated in Josiah’s government. So they could not invent fabulous fairy tales, whatever religious ideology they wanted to promote. They could overstate some measures and they could ignore others — and they did both: they generalized the cult reform, but they ignored the social and national reform attempts — nevertheless, they could not lie. This means that the reliability of the DtrH for the events of the late seventh and early sixth century can be assessed as good, if we take its ideology into account.

The same logic is used to argue for dating the gospels to the generation who “eye-witnessed” the events related, the book of Acts to the late first century, and to date Paul’s letters to the mid-first century. I do not recall ever encountering this type of reasoning to verify historical source material in any relatively modern discussion of historical events in other (non-biblical) fields of enquiry. However, I have seen incredulous remarks of other historians about the methods of their “biblical” peers. See The Bible – History or Story for Davies’ response to this kind of argument.

The very notion that one should give a priori credence to a narrative whose author(s) we do not know, whose time and place of composition we do not know, and whose source materials are equally opaque, is unheard of, I suspect, in other fields of historical inquiry.

In every historical work, whether ancient or modern, the reader can find out from what temporal perspective it was written.

Thus the entire discussion is a weighing of the extent to which biblical texts can be assigned with plausibility to either the seventh or sixth centuries, the time of Josiah or the time of captivity and soon afterwards. The ultimate justification for defaulting to the early Persian era as the “latest most probable” is the silence about any later period in those texts. In this respect, Albertz may have appeared to have overlooked Römer’s point:

We may still ask why are there no direct allusions to the Persian period in DH. Probably because the Dtrs. of the postexilic times were quite »modern« historians: if you write a historiography you do not include your own present.

But he did not overlook it at all. In fact, he found it inadequate as an explanation for the silence:

But [Römer’s] answer, that the Deuteronomistic Historians — like modem ones — avoided including their own present, is not convincing. The present can be excluded or not, but in every historical work, whether ancient or modern, the reader can find out from what temporal perspective it was written. (Albertz, 38)

If we agree with that statement — that a “historical work” cannot avoid betraying (however implicitly) the time perspective from which it is written — then we may argue that the stronger case for the origin of the story of Josiah’s reforms is actually in the Hellenistic period. It is in the Deuteronomistic History that one finds the model of Greek historiography, and even in the Book of Deuteronomy itself as we saw again in the previous post, we see striking correspondences to Greek thought. We also find a historical context in the fluctuating relationships between the Judean and Samaritan peoples and contest over the place of Jerusalem in the Yahweh cult of the early Hellenistic era.

Finally,

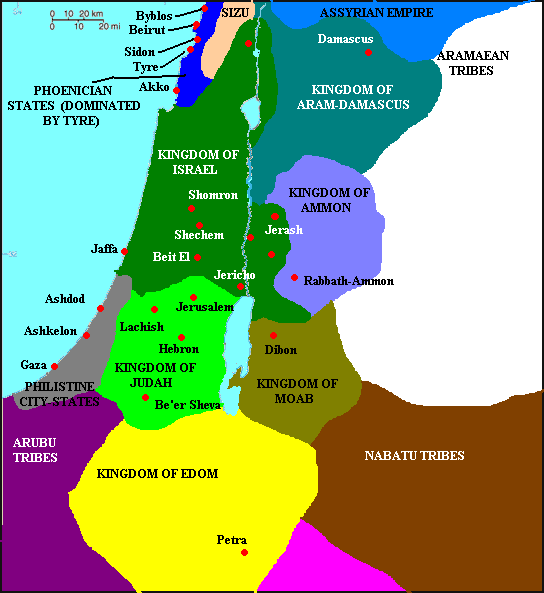

The Historical Evidence

The final point of Albertz’s discussion is “the historical evidence”. For Davies, there was no time when the kingdom of Judah was free from the domination of great powers. After the Assyrians retreated Judah became a vassal of Egypt. Accordingly, there was no period during which Josiah was free to undertake any kind of expansionist policy to try to incorporate the erstwhile northern kingdom of Israel into his control — which, recall, has been claimed to be the reason for Josiah’s propaganda of the Deuteronomistic literature. It was to unite Judah in support of a “single Israel” under one cult based in Jerusalem.

Finkelstein and Silberman accept the reconstruction that has Egypt immediately filling in the space left by the Assyrian withdrawal. In order for them to allow Josiah to undertake his reforms, though, they have to limit the active area of interest of Egypt to the coastal fringes of Canaan. Albertz responds that the evidence is simply too sparse for us to draw any firm conclusions. The argument falls back on a majority view of scholars:

Whatever concrete scenario one might imagine, however, it is interesting to notice that even most of those scholars who think that the domination over Palestine passed uninterrupted from the Assyrians to the Egyptians do not want to deny the possibility of the Josianic reform. (42)

Why Josiah’s Reforms “Must Have Happened”?

There is no evidence in the historical record that they did happen.

But the authors of the biblical literature evidently needed to assign to those texts a history that would lend them credibility.

The literary tradition of discovering lost texts or other sacred artefacts was as old as time, at least as old as ancient Pharaohs and Mesopotamian kings. The motif continued through to Greco-Roman times and beyond. One may even suggest the discovery of Deuteronomy in Josiah’s time has the same level of credibility as Joseph Smith’s discovery of the Book of Mormon. But if the discovery is to have any import, it cannot be told as a simple pedestrian event. Some response that speaks to the extraordinariness of the find is required.

The narrative of Josiah’s reforms in the wake of the discovery “must have happened”. They were as necessary and inevitable as the thunder, lightning, thick cloud and trumpet blast that accompanied the voice of God on Mount Sinai.

Albertz, Rainer. “Why a Reform like Josiah’s Must Have Happened.” In Good Kings and Bad Kings: The Kingdom of Judah in the Seventh Century BCE, edited by Lester L. Grabbe, 27–46. London: T&T CLARK, 2007.

Cross, Frank Moore. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic Essays in the History of the Religion of Israel. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

Davies, Philip R. In Search of “Ancient Israel.” Sheffield, England: Sheffield Academic Press, 1992.

Silberman, Neil Asher, and Israel Finkelstein. The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. New York: Touchstone, 2002.

Gmirkin, Russell E. Plato and the Creation of the Hebrew Bible. New York: Routledge, 2016.

Römer, Thomas C. “Transformations in Deuteronomistic and Biblical Historiography On »Book-Finding« and other Literary Strategies.” Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 109, no. 1 (January 1, 1997): 1–11.

Like this:

Like Loading...