What follows is what I originally planned as the second part of the previous post. My aim is to contribute towards expanding public awareness of material that is otherwise sheltered within cloisters of academic publications and paywalls.

The information here covers the evidence for the Hebrew language being indigenous to Canaan. That means that the Hebrew language was not introduced into Canaan by Israelites or anyone else entering the land as newcomers. Linguistic evidence supports the view that the kingdoms of Israel and Judah emerged from people indigenous to the land of Canaan. The roots of the Hebrew language are found in the Bronze Age, centuries before the emergence of Israel as a distinct political entity.

Think for a moment of other cases where newcomers have occupied land through mass migration. The Anglo-Saxon and Norman invasions of England made their mark in linguistic changes as evidenced in early literary sources. Yet, as philologist Felice Israel remarks, there is no comparable linguistic evidence to be found in the wake of the supposed entry of Israelites into Canaan after their acclaimed exodus from Egypt.

I was led to the evidence for Hebrew origins by a reference in a major 2008 volume on the archaeological finds relating to the religious ideas of Israel’s Syrian neighbours:

Recently, the results of a long study conducted by F. Israel on the general cultural aspects (primarily linguistic), whether innovative or conservative, related to the conquest of Palestine by the tribes of Israel, have been published.352

352 F. Israel, “La conquête de Canaan: observations d’un philologue,” in Antiquités sémitiques IV, Paris 1999, pp. 63-77. I wish to express my gratitude to my colleague F. Israel, who discussed with me the issues presented here.

(Mander, 97)

I immediately requested a copy of Felice Israel’s presentation, (translation = “The Conquest of Canaan: Observations of a Philologist”) from the ever-helpful librarians at the Queensland State Library.

The philologist begins with Israel Finkelstein’s archaeological reconstruction (published 1988) of the emergence of Israel in Canaan and selects the linguistic sources surrounding this period. Finkelstein had identified two phases of settlement expansion of the people who would later be identified in the historical record as consisting of the kingdom of Israel. Where did these settlers come from?

The vast majority of the people who settled in the hill country and in Transjordan during the Iron I period, must have been indigenous . . . . (Finkelstein, 348)

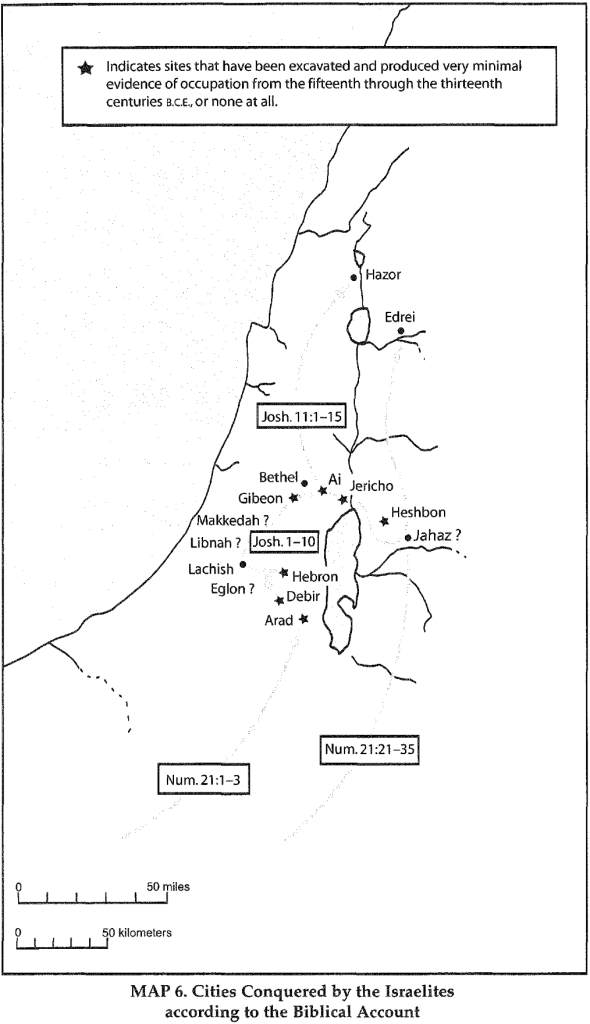

They had “dropped out” of earlier Bronze Age city-state networks that suffered collapse — Shiloh constructions were violently destroyed in the middle Bronze Age and sharp population decline followed. The first phase of the new settlement begins around 1200-1150 BCE (Early Iron Age) with former pastoralists beginning to settle down (left map):

. . . . These people had dropped out of the framework of permanent settlement back in the 16th century BCE and lived in pastoralist groups during the Late Bronze period. While they might have been active all over the country, their presence would have been felt most keenly in the sparsely inhabited ‘frontier zones’ that were suitable for pasturage — the Transjordanian plateau, the Jordan Valley, the desert fringe and the hill country. They had traversed these areas as part of a seasonal pattern of transhumance and established economic relations with the sedentary inhabitants, especially those resident in the few centers existing in these marginal regions, e.g., Shechem and Bethel. (ibid)

— Left map (Finkelstein, 325): first phase of settlement, ca 1200-1150 BCE;

— Centre map (ibid, 329): second phase of settlement expansion, ca 1000-950 BCE “when the last Canaanite enclaves in the Jezreel Valley were subdued and when the Philistines were repulsed from certain areas”;

— Notice the comparative emptiness of what was later Judah: the reason being that this area at the time was very rocky and covered in dense coppice (ibid, 326, 339)

— Right map (added for comparative reference) from Coogan, 6.

So the archaeologist concludes that the population increase in the region destined to become the land of Israel “must have been indigenous”.

The Philologist’s Sources for Assessing Hebrew Origins

Now for the philologist to present her evidence. This consists of . . .

— two inscribed liver models

— a legal document

— a new fragment of a known lexical list

— a vase inscription from the 15th-16th centuries with the name of the owner

— an administrative tablet containing a list of proper names

— a letter

— a mathematical text

— Tell Taanak: letters and name lists

— Shechem: a letter and a contract

— Megiddo: a fragment of the seventh tablet of Gilgamesh

— Gezer: a letter recognized as being from the Amarna period

— Tell el-Hesi: a letter

— Finally, among the various inscriptions from Aphek, the glossary no. 8151 … reveals the evolution of the diphthong ay > ê in the noun yênu, “wine,” as well as the preservation of the monosyllabic nominal form in the noun dušbu, “honey” …

These documents are compared with the Egyptian Amarna archive that contains copies of correspondence with Canaanite city states

(Israel, 65-68 — all quoted text from Felice Israel is my translation)

Felice Israel identifies in these sources specific features that become precursors of the two languages that will, following internal evolution, become Hebrew and Phoenicia. (68) (I have copied the technical information below.*)

The definition in Is. 19:18, according to which the language of Canaan and Hebrew are one and the same language, is thus confirmed. (68 – my highlighting in all quotations)

The above relates to the Bronze Age. We next come to the transition addressed by Finkelstein (above) — the end of the Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, the period of transition of settlement especially in the region that later became known as Samaria/Israel. In this period we see both changes and continuities in the languages of Canaan. But before I list the details of those points and for the benefit of readers less interested in delving into the technicalities, here is the conclusion to the philologist’s observation:

Changes and continuities in the languages of Canaan from Late Bronze to Early Iron Age (ca 1500-1100 BCE)

(I have omitted the footnotes that far exceed the length of the main text)

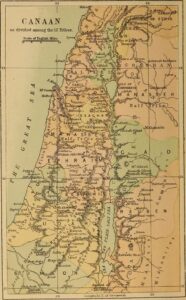

- Dialectal Fragmentation: The distribution of the different Canaanite dialects89 in the first millennium is as follows: on the northern coast of the Levant, various Phoenician dialects are noted, while on the southern coast appears the dialect we have elsewhere called “coastal Canaanite,” which was spoken in the Philistine region.90 In the interior of Palestine, however, we find the Hebrew of the kingdoms of Samaria and Judah, Moabite, the Ammonite dialect, and that of the Edomites.

- Onomastic Innovations: The disappearance of the Hurrian component in Syro-Palestinian onomastics is observed. This component was well present in the documentation of the substrate or, according to traditional terminology, at the time of the “conquest.“91 To the data noted by R. S. Hess92, we can add Hurrian-derived anthroponyms mentioned especially in CAT 4.635 as coming from Ashdod.

- Religious Innovations: The emergence of national or ethnic states is accompanied by the rise of the national god figure93. The history of some of these deities, such as Kamosh or Qaus, has been reconstructed, but for YHWH, as revealed by an investigation conducted by R. S. Hess94, all ancient95 or recent96 attempts to find an attestation of the name outside the Old Testament have been unsuccessful. The only testimony of continuity is the heavenly nature97 of his theophanies, which brings him closer to the figure of Hadad. R. Zadok98 has highlighted the frequency of texts that mention this deity in relation to Palestine.

- Preservation of the Hurrian Substrate: Regarding phonetic conservation, F. W. Bush’s hypothesis99 suggests that the double pronunciation of the bgdkpt consonants in Hebrew and Aramaic is due to the influence of the Hurrian substrate. This influence is not necessarily direct, as it reached Hebrew through contact with Aramaic. For now, it can only be noted that the Hurrian substrate/adstrate, which fully exerts its influence in Ugarit, Nuzi, and Emar, has never been thoroughly studied in the documentation of the first millennium. From an onomastic perspective, few proper names of Hurrian etymology100 have persisted in Old Testament documentation. The most famous of these are Uriah101, the husband of Bathsheba, sent by David to a certain death, and the judge Shamgar ben Anat102. In the lexicon, one of the few preserved Hurrian elements is the term siryôn and the variant siryôn, “cuirass”103.

- Conservation of Egyptian Onomastic Elements: In the onomastic documentation of post-exilic Hebrew, Egyptian etymology104 seems characteristic of priestly proper names.105

- Conservation of Egyptian Lexical Elements: A series of lemmas, which abundantly testify, through their etymology, to the ancient Egyptian presence in the province of Canaan, have been preserved in the Hebrew lexicon. These words can refer to chemical substances, such as neter, “natron”; plants, such as šittâ, “acacia” or gōme’, “papyrus”; semi-precious stones, such as lešem, “carnelian”, aḥlamâ, “jasper”, or šenhabbîm, “ivory”; certain boats, such as ṣî, “type of ship”; or finally, scribal tools like ṭabba‘at, “seal-stamp” or qeset, “scribe’s case.”

- Conservation of Egyptian Administrative Practices: The scribes of the two Israelite kingdoms106 employed and preserved a numerical notation system of a hieratic type107, rather than a Phoenician-Aramaic type. This is confirmed by the presence in the lexicon of measurement unit names such as lōg, hîn, and ʾêpâ, all of Egyptian etymology.

(That last point, #7, relates to the experience of Canaan under Egyptian hegemony in the Late Bronze era.)

—o0o—

* Common precursors of the two languages Hebrew and Phoenicia that indicate they are both indigenous and related.

(I have omitted the footnotes that far exceed the length of the main text)

- The phonetic evolution ā > ō 43: it is attested not only on the coast but also inland, in Galilee and Samaria, extending beyond the Jordan to Pella44. The shift from the etymological ā to ō is foreign to Aramaic45. Moreover, already in the Amarna documentation, it does not appear in regions that, in the first millennium, will be linguistically occupied by Aramaic. This phonetic evolution is absent from both Amorite46 and Ugaritic47.

- Application of the Barth-Ginsberg law48: This law49—yiqtal(u) imperfective < Proto-Semitic yaqtal(u)—also applies in Ugaritic50 but not in Amorite51; in Aramaic, it will apply much later than in Hebrew52.

- The independent personal pronoun of the first person singular anōkî53: The personal pronoun anōkî is a characteristic of Proto-Canaanite54, which is not attested in Ugaritic55 or Amorite56. It anticipates the Hebrew, Phoenician57, and Moabite58 forms.

- The suffix of the perfect first person singular -ti59: This element is also considered a Proto-Canaanite characteristic60. It differs from Ugaritic61 but anticipates the usage in Hebrew, Phoenician62, and Moabite.63

- The independent pronoun ninu64 and the first person plural66 suffix65 pronoun -nu: The appearance of the independent first person plural pronoun ninu is ambiguous because there may be interference between a Canaanite form, which can be reconstructed with a good probability based solely on Hebrew but not Phoenician67, and the usual Akkadian form68. Regarding this, see the analogous spellings attested in the Giblite dossier: da-na-nu-u16 and ni-nu-u16 in EA 362 = LA 168:16, 27. On the other hand, the use of -nu as the suffix of the first person plural perfect69 or as a suffix pronoun70 is a Canaanite characteristic because it anticipates Hebrew usage and differs from the Amorite71 and Ugaritic72 form -na and, at a different time, from the similar Aramaic form -na.73

- The beginning of the pronominalization of the noun ašar74: This transformation of the term75 ašar, “place”76, into a relative pronoun, is not of the Amorite type77 but constitutes an innovation that will be common to Canaanite dialects such as Hebrew78, Moabite79, and Edomite80.

- The modal system81: It seems to anticipate the modal system of Biblical Hebrew. The cohortative form yaqtula anticipates, for example, the Hebrew cohortative in an obvious way.82

- The use of the internal passive83: It actually anticipates the reduction to only seven verbal conjugations, which will be typical of standard Hebrew and Phoenician.84

Coogan, Michael D., ed. The Oxford History of the Biblical World. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Finkelstein, Israel. The Archaeology of the Israelite Settlement. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1988.

Horowitz, Wayne. “A Combined Multiplication Table on a Prism Fragment from Hazor.” Israel Exploration Journal 47, no. 3/4 (1997): 190–97.

Horowitz, Wayne, and Aaron Shaffer. “A Fragment of a Letter from Hazor.” Israel Exploration Journal 42, no. 3/4 (1992): 165–67.

Israel, Felice. “La Conquête de Canaan: Observations d’un Philologue.” In Guerre et conquête dans le Proche-Orient ancien: actes de la table ronde du 14 novembre 1998, edited by Laïla Nehmé and Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, 63–77. Antiquités sémitiques. Paris: Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient, 1999.

Landsberger, B., and H. Tadmor. “Fragments of Clay Liver Models from Hazor.” Israel Exploration Journal 14, no. 4 (1964): 201–18.

Mander, Pietro. “Les Dieux et Le Culte à Ébla.” In Mythologie et Religion des Sémites Occidentaux. Volume 1, Ébla, Mari, edited by Gregorio del Olmo Lete, 1–160. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta. Leuven: Peeters, 2008.

Tadmor, Hayim. “A Lexicographical Text from Hazor.” Israel Exploration Journal 27, no. 2/3 (1977): 98–102.

Yadin, Yigael, Yohanan Aharoni, Ruth Amiran, Trude Dothan, Immanuel Dunayevsky, and Jean Perrot. Hazor II: An Account of the Second Season of Excavations, 1956. Jerusalem : Magnes Press, Hebrew University, 1960. http://archive.org/details/hazoriiaccountof0000jame.