Josephus does, in Jewish Antiquities, have two passages on the emergence of Christianity and the persecution of its followers, involving Jewish jurisdiction, but both are suspected of being interpolations. (Efron 1987, p. 333)

Warning: this post addresses a small section of a work by Jewish scholar, Joshua Efron, Studies on the Hasmonean Period, that was not been well received by all reviewers. John Collins, for example, wrote of the section that I cover here:

The final chapter, on the Great Sanhedrin, is peripheral to the main theme of the book. E. denies that there was any uniform tradition about the Great Sanhedrin, but finds that the NT Sanhedrin “was created in the bosom of Christian theology” (p. 337).

Efron’s book shows extensive familiarity with the history of scholarship and is richly documented, but it is a work of apologetics rather than of history. For E., the solidarity of pietism and the Jewish state is primary. Any contrary view is “distorted.” Equally, anything that seems to anticipate Christian theology cannot be Jewish. (Collins 1990, p. 373 — my emphasis)

Louis Feldman is less harsh in his review but nonetheless identifies the bias. Efron attacks contemporary scholarly reconstructions of various intra-Jewish political rifts and conflicts in “a strident tone” and dismisses anything that would blur Jewish distinctiveness from Christianity:

The main, and most controversial, thesis of this work is that the Hasidim and the Hasmoncans cooperated throughout their revolt against the Syrian Greeks, and that this cooperation continued with the later Pharisees. The reconstruction of this period often rests upon the Pseudepigrapha, notably the Psalms of Solomon. But Efron dismisses such evidence as betraying a hidden Christian viewpoint . . . (Feldman 1994, p. 87)

You have been warned. Read at your own peril. Read critically (as you always do).

–o–

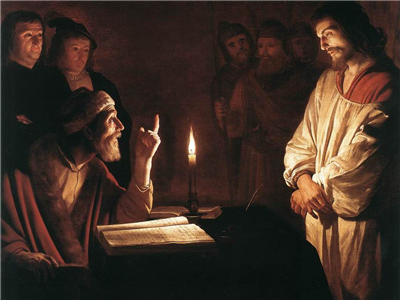

About this time there lived Jesus, a wise man, if indeed one ought to call him a man. For he was one who performed surprising deeds and was a teacher of such people as accept the truth gladly. He won over many Jews and many of the Greeks. He was the Christ. And when, upon the accusation of the principal men among us, Pilate had condemned him to a cross, those who had first come to love him did not cease. He appeared to them spending a third day restored to life, for the prophets of God had foretold these things and a thousand other marvels about him. And the tribe of the Christians, so called after him, has still to this day not disappeared. (Antiquities, 18.3.3)

Many readers are familiar with the passages. The first, known as the Testimonium Flavianum, describes Jesus as “a wise many if one ought to call him a man” and even states that “he was the Messiah” and his followers were righteous “seekers of the truth”, he performed miracles, was unjustly condemned to death at the instigation of the Jews, appeared to have been resurrected three days later, etc. If Josephus wrote the passage as we have it then he was clearly himself a Christian and we are left perplexed over everything else he wrote in defence of “Judaism”.

The fourth century bishop Eusebius quoted the passage but the third century Origen did not see it in his copy of Josephus.

But don’t many scholars agree that the passage as it stands cannot have been written by Josephus while remaining certain he must have written something about Jesus nonetheless? Many do. Efron’s opinion of these efforts:

Various proposals, speculations and attempts to reconstruct from it some authentic core have produced only dubious hypotheses.213

213 . . . . The scholars positing authenticity (complete, partial or emended) have recourse to casuistic speculations or arbitrary textual alterations. See R. Laqueur, Der jüdische llistoriker Flavius Josephus (Giessen 1920), p. 274ff.; H.St. J. Thackeray, Josephus the Man and the Historian (New York 1967, repr. of 1929ed.),p. 125ff.; F. Dornseiff, “Zum Testimonium Flavianum,” ZNW 46 (1955): 245ff.; A. Pelletier, “Ce que Josephe a dit de Jesus,” KEJ 124 (1965): 9ff.; D. Flusser (see n. 190), Yahadut u-Mekorot ha-Natzrut, p. 72ff .; F.F. Bruce, Jesus and Christian Origins Outside the New Testament (Gr. Rapids Mich. 1974), p. 32ff.

And once more:

Classic examples of the practices of Christian copyists and editors in transposing suitable additions and adding them to Josephus can be found in the Slavonic version of Jewish War.

The arguments have gone back and forth “for generations” (Efron’s words) and we have posted at length on them here.

And now Caesar, upon hearing the death of Festus, sent Albinus into Judea, as procurator. But the king deprived Joseph of the high priesthood, and bestowed the succession to that dignity on the son of Ananus, who was also himself called Ananus. Now the report goes that this eldest Ananus proved a most fortunate man; for he had five sons who had all performed the office of a high priest to God, and who had himself enjoyed that dignity a long time formerly, which had never happened to any other of our high priests. But this younger Ananus, who, as we have told you already, took the high priesthood, was a bold man in his temper, and very insolent; he was also of the sect of the Sadducees, who are very rigid in judging offenders, above all the rest of the Jews, as we have already observed; when, therefore, Ananus was of this disposition, he thought he had now a proper opportunity. Festus was now dead, and Albinus was but upon the road; so he assembled the sanhedrin of judges, and brought before them the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James, and some others; and when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned: but as for those who seemed the most equitable of the citizens, and such as were the most uneasy at the breach of the laws, they disliked what was done; they also sent to the king, desiring him to send to Ananus that he should act so no more, for that what he had already done was not to be justified; nay, some of them went also to meet Albinus, as he was upon his journey from Alexandria, and informed him that it was not lawful for Ananus to assemble a sanhedrin without his consent. Whereupon Albinus complied with what they said, and wrote in anger to Ananus, and threatened that he would bring him to punishment for what he had done; on which king Agrippa took the high priesthood from him, when he had ruled but three months, and made Jesus, the son of Damneus, high priest. (Antiquities, 20.9.1)

We have also discussed the second passage at length. But Efron has more to add and the rest of this post sets out why he also rejects this passage as genuine to Josephus.

Efron observes that this second passsage (see inset) portrays the Sanhedrin in a way very similar to the New Testament’s viewpoint: very harsh, even evil. Likewise the Sadducees are said to be “very rigid” or “severe”, translatable as “savage” (Efron), more than any other Jews. And Ananus belongs to this “savage” sect and is further described as “extremely bold and brazen”.

Enough good citizens, however, complained to the authorities about the injustice against James committed by Ananus and had him removed from the priesthood.

1. Unfavorable portrait of Ananus is polar opposite to Josephus’ views

Efron sees in these portrayals of the Sanhedrin, the Sadducees and Ananus too much New Testament. In Josephus’s earlier work on the Jewish War we find Josephus expressing the “polar opposite” view of Ananus, “overwhelming him with praise”, “devoting an emotional eulogy to him”. As for the Sadducees, Josephus in the earlier work never betrayed a hint that they were in any way to be faulted for their religious practices and views.

Could not Josephus have changed his mind by the time he wrote Antiquities?

It is true that opinions and evaluations sometimes change in Josephus’ second and more critical version. Thus, in his apologetic autobiography, Josephus in self defense somewhat dims Ananus’ lustre, but there is no trace of a diametrically opposite view of him.216 Acts of the Apostles, however, in a picture resembling the dubious episode outlined above, stresses the unfavorable aspects of Ananus (Annas) the high priest, and his Sadducee retinue, avidly persecuting the Christians without pity.218

216 Bell. II 563, 648, 651, 653; IV 151ff., 162ff. 193ff., 208ff., 288ff., 316ff.; Vita (38) 193ff.;(44) 216, (60) 309.

218 Acts 4:6ff.; 5:17ff.; Luke 3:2; John 18:13ff. To the two forged passages should be added the extremely suspect testimony in Josephus (Ant. XVIII 116 ff.) on John the Baptist carrying out a baptismal ceremony in the Christian spirit to atone for sins, without a sacrifical offering and without the Temple, contrary to the Torah. The term “the Baptist” and the man, unknown in Jewish tradition, as is baptism to obtain forgiveness for sins through purification of the body after purification of the soul (as in Heb. 10:22) show this to be a Christian version. A number of scholars came to this conclusion long ago: D. Blondel, Des Sibylles (Paris 1649), p. 28 ff.; Richard Simon (Mr. de Sainjore), Bibliotheque Critique, vol. 2 (Paris 1708), p. 26ff.; H. Graetz, Geschichle (see n. 8 above), vol. 33, p. 293 ff. Origen (n. 223 below) already knew the dubious passage: Contra Celsum 147. (Efron 1987, pp. 334-35)

2. Another “astounding connection with … Acts”

Who are the “most equitable of citizens” who opposed the Sadducees? The Josephan passage is vague. To Efron, Continue reading “6 More Reasons to Question Josephus’ “James the brother of Jesus” passage”

Like this:

Like Loading...