How or from where did Christianity get the idea that the Messiah was also the Son of God? It is easy to get the idea that the standard belief among scholars is that there was a gradual evolution of Christological concepts, that over time Jesus became ever more exalted in the minds of worshipers. But the evidence of early Jewish writings points us to another explanation, one that leads us to think that the idea that the Davidic Messiah was also a Son of God was part of the same idea from the beginning.

As I prepared to write the next instalment on Nanine Charbonnel’s Jésus-Christ, Sublime Figure de Papier I found myself burrowing down into more citations than I could hope to fit into such a post. So here I address just one detail as a stand-alone composition.

This post has a narrow focus. It zeroes in on the early evidence, from before the Christian era up to the first century CE, that among Jewish sectarian ideas there was one that explicitly identified the Davidic Messiah with the Son of God. I do not address questions of the actual meaning of “son of God” — except insofar as the label is applied to a pre-existent and heavenly being as well as an earthly king. The two become fused.

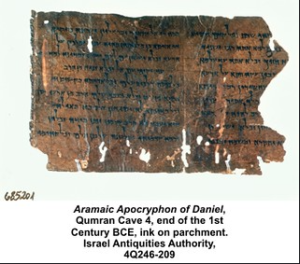

The fusion of the heavenly ‘son of man’ figure envisaged in Daniel, with the traditional hope for a Davidic Messiah was of fundamental importance for early Christianity. The ‘Son of God’ text from Qumran shows that this fusion did not originate in Christianity, but was already at home in sectarian Jewish circles at the turn of the era. (Collins, 82)

The term Son of God in Jewish writings has many different applications: angels, the king of Israel, the people of Israel, righteous Israelites (Jubilees 1:24-25) — and the royal messiah. This post looks at the instances where Son of God is directly applied to that messiah king.

The Davidic branch is identified as the Son of God in Qumran texts.

The branch of David is explicitly identified with the Messiah in 4Q252: . . . there shall not fail to be a descendant of David upon the throne . . . until the Messiah of Righteousness comes, the Branch of David . . .

I will establish the throne of his kingdom f[orever] (2 Sam 7:13). I wi[ll be] a father to him and he shall be a son to me (2 Sam 7:14). He is the branch of David who shall arise . . . in Zi[on in the la]st days . . . (4Q174)

. . . when God has fa[th]ered the Messiah . . . (1QSa/1Q28a)

Similarly in the Jewish apocryphal work 4 Ezra:

For my son the Messiah shall be revealed with those who are with him, and those who remain shall rejoice four hundred years.

And after these years my son the Messiah shall die, and all who draw human breath. (4 Ezra 7:28f)

4 Ezra 13 is dependent on Psalm 2: the messianic figure stands on a mountain and repulses the attack of the nations; God sets his anointed king on his holy mountain, terrifies the nations, and tells the king “you are my son…”

Daniel 7 also inspires 4 Ezra 13: vision of a man emerging from the sea and flying with the clouds, preceded by war among the nations. (Collins p. 76f)

And when these things come to pass and the signs occur which I showed you before, then my Son will be revealed, whom you saw as a man coming up from the sea. (4 Ezra 13:32)

And he, my Son, will reprove the assembled nations for their ungodliness (this was symbolized by the storm) (4 Ezra 13:37)

He said to me, “Just as no one can explore or know what is in the depths of the sea, so no one on earth can see my Son or those who are with him, except in the time of his day. (4 Ezra 13:52)

for you shall be taken up from among men, and henceforth you shall live with my Son and with those who are like you, until the times are ended. (4 Ezra 14:9)

The Book of Enoch

More specifically, the Epistle of Enoch in the Book of Enoch, dated between 170 BCE and the first-century BCE. . . .

More specifically, the Epistle of Enoch in the Book of Enoch, dated between 170 BCE and the first-century BCE. . . .

In Enoch 105:1-2 (mistakenly cited as 55:2 in Charbonnel’s source)

1. In those days the Lord bade (them) to summon and testify to the children of earth concerning their wisdom: Show it unto them; for ye are their guides, and a recompense over the whole earth. 2. For I and My Son will be united with them for ever in the paths of uprightness in their lives; and ye shall have peace: rejoice, ye children of uprightness. Amen.

There is debate over the identities of “I and my son” in Enoch. Some scholars have suggested it might refer to Enoch and his son Methuselah. George W. E. Nickelsburg in his commentary writes

In the context of chaps. 81 and 91, “I and my son” here could mean Enoch and Methuselah rather than God and the Messiah, as Charles suggested.11

11 Charles, Enoch, 262-63.

(1 Enoch 1, p. 535)

His note 11 is a problem, at least it is for me. There are four titles in his bibliography that it could refer to.

- Charles, R. H. The Book of Enoch: Translated from Dillmann’s Ethiopic Text, emended and revised in accordance with hitherto uncollated Ethiopie MSS. and with the Gizeh and other Greek and Latin fragments (Oxford: Clarendon, 1893).

- Charles, R. H. The Book of Enoch, or 1 Enoch: Translated from the Editor’s Ethiopic Text, and edited with the introduction notes and indexes of the first edition wholly recast enlarged and rewritten; together with a reprint from the editor’s text of the Greek fragments (Oxford: Clarendon, 1912).

- Idem “Book of Enoch,” in idem, ed., The Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha of the Old Testament, volume 2, Pseudepigrapha (Oxford: Clarendon, 1913) 163-281.

- Idem The Book of Enoch (Translations of Early Documents, Series 1; London: SPCK, 1917).

Wanting to read what Charles had to say I consulted the third title listed above (1913) and found Charles identifying the Messiah with God’s Son:

105:2. I and My Son, i.e. the Messiah. Cf. 4 Ezra vii. 28, 29, xiii. 32, 37, 52, xiv. 9. The righteous are God’s children, and pre-eminently so the Messiah. Cf. the early Messianic interpretation of Ps. ii, also I En. lxii. 14 ; John xiv. 23. (Charles 1913, p. 277)

In the first title (1893) I found the same identification:

The Messiah is introduced in cv. 2, to whom there is not the faintest allusion throughout xci-civ. . . . To My Son. There is no difficulty about the phrase ‘My Son’ as applied to the Messiah by the Jews : cf. 17 Ezra vii. 28, 29 ; xiv. 9. If the righteous are called ‘God’s children’ in lxii. 11, the Messiah was pre-eminently the Son of God. Moreover, the early Messianic interpretation of Ps. ii would naturally lead to such an expression. (Charles, 1893, p. 301)

Charles does say that the reference to the Messiah seems out of place in the context of the preceding chapters but for that reason thinks a different author is responsible for the passage being inserted. Michael A. Knibb has this to say:

[T]he possibility that there are Christian elements within the Ethiopic version of 1 Enoch — beyond, that is, the presence of occasional Christian glosses — needs to be considered, as has been suggested in relation to 105:2a and chapter 108. Chapter 105 comes at the end of Enoch’s admonition to his children, and the Aramaic evidence (4QEnc 5 i 21–25) showed that the material in this chapter . . . did form part of the original. But 105:2a (“For I and my son will join ourselves with them for ever in the paths of uprightness during their lives”) was apparently not in the Aramaic. It may well represent a Christian addition, but such a statement is not impossible in a Jewish context.63 . . . and it is possible that . . . 105:2a [is not] Christian.

63 Cf. 4Q246 ii 1; Knibb, “Messianism in the Pseudepigrapha in the Light of the Scrolls,” DSD 2 (1995): 165–84 (here 174–77).

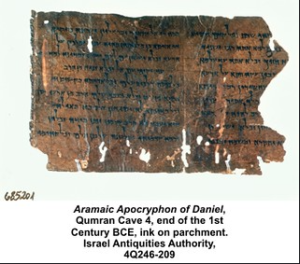

The Son of God Text

4Q246:

— Opening verse of column 1: someone falls before the throne;

following verses seem addressed to a king and refer to “your vision“;

— then, “affliction will come on earth … and great carnage among the cities“;

— a reference to kings of Asshur and Egypt;

— verse 7 reads “will be great on earth” (does this refer to the great affliction of preceding verses or the great figure of the following verses?);

— line 8 says “all will serve” and then, “by his name he will be named“.

— Then column 2 opens with our famous line quoted in the post (ii 1)

So we come to 4Q246, “better known as the ‘Son of God’ text” (Collins). See the side box for an overview, but the key line of interest to us:

He will be called the Son of God, they will call him the son of the Most High (ii 1)

Following this line we read about a kingdom destined to rule the earth, trampling all, until the people of God rise up and “all rest from the sword“. His kingdom is an everlasting kingdom and righteous; the sword will cease; all cities will pay homage; God will be its/his strength and make war on its/his behalf, giving the prostrate nations to him/it; its rule is everlasting. (I have relied on Collins for this summary.)

The remainder of this post follows selected points from an article by John Collins, “The Son of God Text from Qumran”, in From Jesus to John: Essays on Jesus and New Testament Christology in Honour of Marinus de Jonge, with a few glances at Knibb’s work.

The correspondences with the infancy narrative in Luke are astonishing. — Collins, p.66

Three phrases correspond exactly:

will be great, (Luke 1:32)

he will be called the son of the Most High (Luke 1:32)

he will be called the Son of God (Luke 1:35)

Luke also speaks of an unending reign. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that Luke is dependent in some way, whether directly or indirectly, on this long lost text from Qumran.

(Collins, 66, my formatting and highlighting)

Continue reading “When the Messiah Became the Son of God in Early Jewish Thought”

Like this:

Like Loading...