[Author’s note: I wrote this back in 2014, but decided to put in on the back burner for a bit, setting the publication clock five years ahead. The post below, which auto-published yesterday, is not actually finished. I will soon submit a third part to this series, with a summation and conclusions. taw]

Rendsburg’s thesis

As we discussed in part 1, Gary Rendsburg believes that we shouldn’t try to divide the Genesis flood story based on supposed source documents, namely the Yahwist (J) and the Priestly (P) sources. He writes:

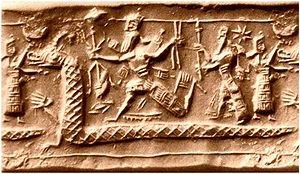

If one reads the two stories as separate entities, one will find that elements of a whole story are missing from either the J or the P version. Only when read as a whole does Genesis 6-8 read as a complete story, and — here is the most important point I wish to make — not only as a complete story, but as a narrative paralleling perfectly the Babylonian flood story tradition recorded in Gilgameš Tablet XI, point by point, and in the same order. Perfectly, that is, after taking into account elements found in the biblical narrative but lacking in the Babylonian story, indicated by a minus sign in the right hand column of the accompanying chart — given the distinctively Israelite theological position inherent to Genesis 6-8 . . . (Rendsburg, 2004, p. 115-116)

We’ll save Rendsburg’s chart for the end. For now, let’s examine his argument closely and see if it holds up under close scrutiny.

Essentially, Rendsburg is offering a counter-argument to the consensus view that the redactor of Genesis pulled together two sources (J and P), which most likely both came from the earlier Babylonian and Sumerian myths. Instead, he maintains that the author of Genesis appropriated the flood story directly from the Gilgamesh epic, adding only those theological elements peculiar to the Israelite religion. His argument depends on proving the coherence and unity of the Genesis story, combined with the “perfect” correspondence between the order of events in Genesis and in Tablet XI of the Gilgamesh epic.

In his audio course on the book of Genesis, Rendsburg says:

Materials, dimensions, and decks

Now note that not only are all these [story] elements present, one by one, as we work through the two stories that we are comparing here, but that they are also in the same order. Now, in certain cases, of course, there is no opportunity for a variation in the order. That is to say, you have to build the ark before the flood comes, and the flood has to come before it lands on a mountain top, and so on. But even where there is room for variation, the two stories proceed, element by element, in the same order.

Let me give you an example of that. In the Gilgamesh story the materials, the dimensions, and the decks are given in that order; in the biblical story the materials, the dimensions, and the decks are given in that order. And of course, you may say, “Well, that’s perfectly logical — how else would you else would you instruct somebody to build a vessel?” But nevertheless, it’s still noteworthy. (Rendsburg, 2006a, 7:38, emphasis mine)

I have to confess that even if Rendsburg is correct, I don’t find his argument persuasive. Consider the possibility that the J and P source material both (independently) borrowed from the story of Utnapishtim or, for that matter, from the earlier story of Atrahasis. We could reasonably assume that each story would generally follow the same sequence, and that the redactor would have little reason to deviate from that sequence.

We should note here that with his presentation of the evidence Rendsburg is in fact trying to prove two points: first, that the flood story in Genesis is secondary to the older flood myths of Mesopotamia, and second, that the order of events in Noah’s flood tale “perfectly” parallel the events as told by Untapishtim in the Gilgamesh epic. Moreover, he argues, that perfect correspondence falls by the wayside if we try to split the Genesis story into its source components.

With all of that in mind, let’s examine his first claim, viz. that the two stories relate “materials, dimensions, and decks” in that order. Sure enough, in Genesis here’s the order:

Materials

6:14 Make for yourself an ark of gopher wood; you shall make the ark with rooms, and shall cover it inside and out with pitch.Dimensions

6:15 This is how you shall make it: the length of the ark three hundred cubits, its breadth fifty cubits, and its height thirty cubits.Decks

6:16 You shall make a window for the ark, and finish it to a cubit from the top; and set the door of the ark in the side of it; you shall make it with lower, second, and third decks. (NASB)

Now let’s take a look at the story as told by Utnapishtim. Ea does not directly tell our hero that a flood is coming. Rather, he talks to a reed hut, which just happens to be Utnapishtim’s dwelling. That is to say, he whispers through the wall of the hut in order to pass on his instructions. Ea says:

24. Tear down (thy) house, build a ship!

25. Abandon (thy) possessions, seek (to save) life!

26. Disregard (thy) goods, and save (thy) life!

27. [Cause to] go up into the ship the seed of all living creatures.(Heidel, 1949, p. 81)

We already see significant differences between the two stories. God tells Noah to collect materials to build an ark, literally a box (similar to the “chest” built by Deucalion). On the other hand, Ea indirectly tells Utnapishtim to dismantle his house and build a ship.

In what order does Ea provide his ship-building instructions?

28. The ship which thou shalt build,

29. Its measurements shall be (accurately) measured;

30. Its width and its length shall be equal.

31. Cover it [li]ke the subterranean waters.’(Heidel, 1949, p. 81, emphasis mine)

Ea is already discussing the dimensions and characteristics of the boat, but he hasn’t yet mentioned anything about materials. (We would remind Dr. Rendsburg that width and length are what we call “dimensions.”) In line 31 we have a clue that the boat will differ from ordinary in that it needs to be covered, presumably to keep out the coming torrential rains. Of course, since his job will be to save all life, Untapishtim’s boat will naturally need to be rather large.

We might theorize that if Utnapishtim will be using materials from his torn-down dwelling, reeds will be involved. Far from forests, the people of ancient Mesopotamia built their houses and boats out of reeds. In cases where they did use wood (e.g., for seagoing vessels), it was probably only for the keel, spars, oars, and punting poles. (See Mäkelä, 2002, for details on ancient shipbuilding in Mesopotamia.) That said, some scholars have suggested that the “water-stoppers” mentioned in line 63 refer to wedge-shaped chunks of wood driven into the seams to prevent leaking.

In fact, we have no explicit evidence of wood as a building material in the Gilgamesh epic, but we do have clues in the earlier Babylonian flood story from which it is derived. On tablet III, lines 48-51 we find:

The carpenter [carried his axe],

The reed-worker [carried his stone],

[The rich man? carried] the pitch,

The poor man [brought the materials needed].(Foster, 1995, p. 72)

[Note: Some reconstructed texts of the Gilgamesh epic insert the lines concerning the carpenter and reed-worker above line 54. However, it is not actually part of the received text.]

Ea provides no more specifics on building the ship, although lines 50 through 53 are usually considered too fragmentary to translate. We do find out that pitch plays a role from line 54:

54. The child [brou]ght pitch,

55. (While) the strong brought [whatever else] was needful.(Heidel, 1949, p. 82)

Utnapishtim then describes the measurements in greater detail:

56. On the fifth day [I] laid its framework.

57. One ikû [about an acre] was its floor space, one hundred and twenty cubits each was the height of its walls;

58. One hundred and twenty cubits measured each side of its decks.(Heidel, 1949, p. 82)

So, what of Rendsburg’s claim that the two stories match perfectly when compare side by side? His first test case fails on the evidence. Ea does not follow the same pattern as God in Genesis. Indeed, we do not see references to “materials, dimensions, and decks . . . in that order.” Ea starts with a command to build a ship, and immediately starts talking about its dimensions (again, see lines 29 and 30).

As far as we can tell from the text, the god never talks about materials, presumably because Utnapishtim is building a known structure: a boat (albeit of unusual size). We do finally get references to “decks,” but not until line 58.

Wood, reeds, and pitch

Rendsburg desperately wants to find perfect correspondence — so much so that he insists on a rather unusual translation of Genesis 6:14. He writes in the course guide:

Note that all translations agree on two of the building materials for the ark: wood and pitch. The third item is the subject of some discussion, however. The consonants in the biblical text, namely, QNYM, can be read as either qinnim, “rooms, compartments” (thus the traditional rendering), or qanim, “reeds” (thus some recent translations). We favor the latter understanding, especially because reeds constitute the third building material in the Gilgamesh Epic flood narrative. (Rendsburg, 2006b, p. 16)

I won’t try to argue Hebrew with Rendsburg. I will only mention the following two points:

- The translation of the word in the text as “reeds” rather than “rooms” is exceedingly rare. No major translation in English uses it. In fact, other than the Everett Fox translation and commentary that Rendsburg cites, I know of no other translation that uses it.

- If we go with “compartments” (as the vast majority of translators do), we still have a viable parallel in the Gilgamesh epic, namely:

59. I ‘laid the shape’ of the outside (and) fashioned it [the ship].

60. Six (lower) decks I built into it,

61. (Thus) dividing (it) into seven (stories).

62. Its ground plan I divided into nine (sections).(Heidel, 1949, p. 82, emphasis mine)

Hence, we have good reason to believe that the author of the P source inherited the tradition that the ship (or in his case, the ark) that saved all animal life had various sections or compartments.

Mountain landing, then birds

Where else might we find the perfect correspondence that Rendsburg craves? He continues (in his lecture):

Perhaps at the end is where we can see the room for some variation. That is to say, it might have been to send out the birds first, and then have the ark to land on a mountaintop. But no, in both stories the mountaintop landing occurs first, and then the birds are sent forth. (Rendsburg, 2006, 8:27)

In print, Rendsburg concedes the alternative order is improbable.

I agree that such an order of events is far less likely than the order which appears in the biblical narrative. but it is possible nonetheless. It is therefore pertinent to point out that Genesis 8 parallels the Babylonian flood story, with the mountain top landing preceding the sending forth of the birds. (Rendsburg, 2007, p. 117)

I would argue that it simply makes more narrative sense for the flood hero to realize they’ve come to a stop, wonder about where they might be and whether it’s safe to leave, and only then hit upon the idea of using the birds. In other words, the mountain landing causes Noah and Utnapishtim to send out the birds. Hermann Gunkel comments:

The following, lovingly presented scene (6b- 12, 13b) has the goal of portraying the exceedingly great wisdom of Noah. No one in the Ark knows where they are and how things look outside. No one dares open the door—great streams of water could surge in—or take off the roof—the rain could begin again. One can look out the window, but through it one sees only the heavens above. What shall one do? How shall one learn whether the earth is dry? In this difficult situation the clever Noah knows a means. If one cannot exit oneself, one can send the birds to reconnoiter. “It was an old nautical practice, indispensable in a time which did not know the compass, to bring birds along to be released on the high seas so that the direction to land could be determined by their flight” [quoting Hermann Usener in Die Sintfluthsagen] . . . (Gunkel, 1997, p. 64, emphasis mine)

Liberation, then sacrifice

We have saved for last what Rendsburg considers his strongest argument. Again, from his audio course:

And most importantly, I think the place for . . . the best possibility of variation is the very, very end of the story where it’s very possible that the flood hero — Noah or Utnapishtim — could have done the sacrifices before letting everybody go free. But no, in both stories all are set free, and then the sacrifices occur. So I repeat the statement here: Element by element the two stories — the Gilgamesh Epic, Tablet XI (the Babylonian flood tradition), and the biblical story with Noah as its hero in Genesis 6 through 8 — tell the tale one by one, element by element in the same order. (Rendsburg, 2006a, 8:45)

He really does think it’s his strongest argument. In his 2004 article he wrote:

I refer especially to the end of the story, where both Noah and Utnapishtim could have performed the sacrifices first. While all were still on the ark, and only later everyone free. But in both cases the order is first to set everyone free and then to perform the sacrifices. In Noah’s case, in fact, the order is counterintuitive. If he first set all the animals free and then performed the sacrifices, as the story now reads, one might ask. What happened? Did he call the pure animals back in order to sacrifice them? (Rendsburg, 2004, p. 117)

Obviously, the implication is clear: Noah set all the animals free, except for the handful which he intended to sacrifice. But my point is this: if the redactor had before him two stories, the supposed J account and the supposed P account, the former including the sacrifices and the latter including the hero’s setting everyone free, I would imagine that the redactor would have woven his story with these two elements in that order the sacrifices first, while the animals were still present, and then the setting of everyone free. But such is not the case. At the end of Genesis 8. Noah first sets the animals free and then performs the sacrifices.

Sources

Foster, Benjamin R.

From Distant Days: Myths, Tales, and Poetry of Ancient Mesopotamia, CDL Press, 1995

Gunkel, Hermann

Genesis [Translated and Interpreted by Hermann Gunkel], trans. Biddle, Mercer University Press, 1997 (English translation of 1910 edition)

Heidel, Alexander

The Gilgamesh Epic and Old Testament Parallels, The University of Chicago Press, 1949

Mäkelä, Tommi Tapani

“Ships and Shipbuilding in Mesopotamia (PDF),” Texas A&M University Graduate Thesis, 2002

Rendsburg, Gary

“The Biblical Flood Story in Light of the Gilgameš Flood Account,” pp. 115-127, Gilgamesh and the World of Assyria, ed. Azize J., Weeks N., Peeters, 2007

“Genesis 6-8, The Flood Story (Lecture 7),” The Book of Genesis, The Great Courses, 2006a

“Lecture 7: Genesis 6-8, The Flood Story,” The Book of Genesis (Course Guide), The Great Courses, 2006b

Wellhausen, Julius

Prolegomena to the History of Israel, trans. Black and Menzies, Adam and Charles Black, 1885