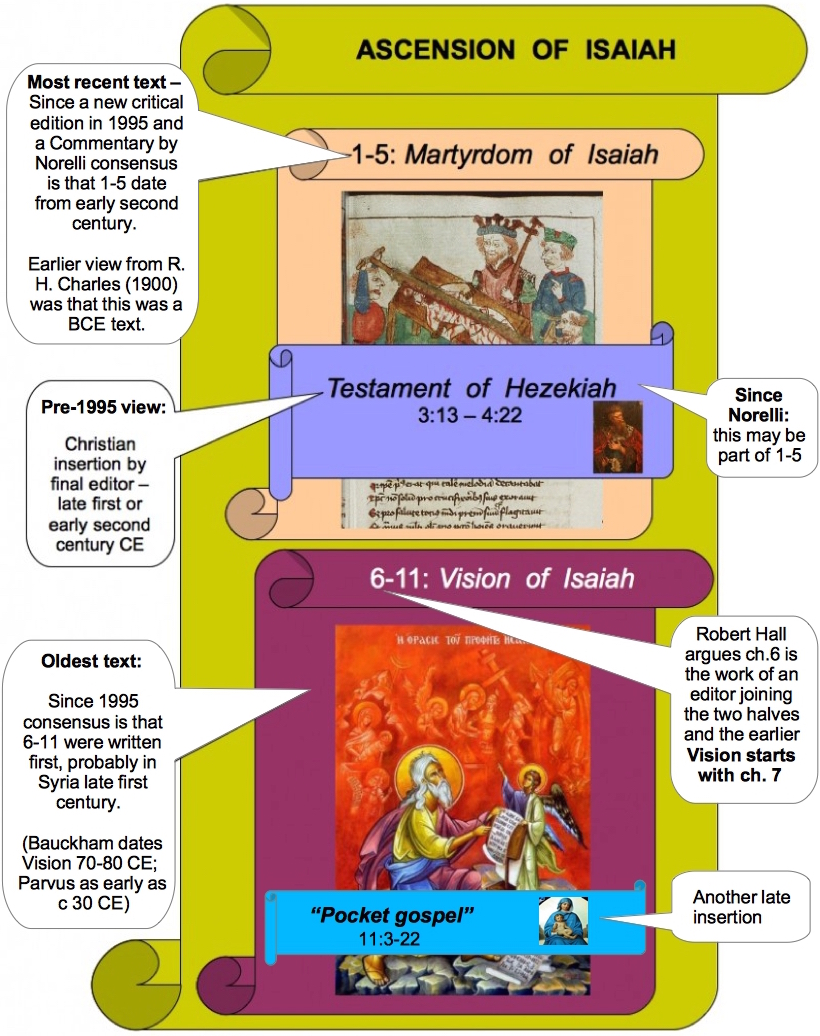

This post revises a hypothesis I proposed a few years ago in the Vridar series “A Simonian Origin for Christianity.” In those posts I argued for a scenario in which Paul was in reality Simon of Samaria, and the seven allegedly authentic Pauline letters were in fact letters of Simon that, in the early second century CE, received a makeover by some proto-orthodox Christians. By means of certain additions and modifications to the letters these people in effect co-opted Simon’s work and turned him into a proto-orthodox Paul. I argued too that the gospel message embraced by the author of the original letters was some form of the Vision of Isaiah (chapters 6-11 of the Ascension of Isaiah).

I had misgivings about the hypothesis even before I finished the series, but two years of mulling it over has left me even less enamoured. I am still quite convinced that the Vision of Isaiah is the correct background for several key passages: 1 Cor. 2:6-9; Phil. 2:6-11; 2 Cor. 12:1-10. I have come to doubt, however, that these passages belong to the earliest parts of the letter collection. My changed understanding of 2 Cor. 12:1-10 in particular has led me to think it more plausible that the bulk of the letters was composed not by Simon but by later followers of his who converted to Christianity sometime between 70 and 135 CE. In my revised scenario Paul, not Simon, is the author of the original letters; and the bulk of the additional material — material that turned letters into epistles — was likely composed by a circle of Saturnilians, a community founded by the ex-Simonian Saturnilus of Antioch. Proto-orthodox input consisted of some final sanitizing touch-ups.

This revised scenario bears a definite resemblance to that of the biblical scholar Alfred Loisy (1857-1940) and I acknowledge that a re-reading of his later writings has contributed to my change of heart. Loisy held that only a kernel of the seven allegedly authentic Paulines really went back to Paul, and that the rest consisted largely of stitched-together late first, early second-century materials. He characterized many of these materials as gnostic but preMarcionite. Where I go further than Loisy is in recognizing the role of the Vision of Isaiah in the letters, and in proposing a specific provenance for their incipient gnosticism: Saturnilian Christianity.

Before I explain this revised scenario in more detail I should first review the Pauline texts that show, in my opinion, that their author knew the Vision of Isaiah. It is clear, in general, that the Vision would be a congenial text for Paul’s congregations, for Isaiah is described as receiving his revelation in the midst of a gathering of forty prophets. They look to him for guidance and

And they had come to greet him, and to hear what he said. And they hoped he would lay his hands on them and that they might prophesy and he would listen to their prophecy (Asc. Is. 6: 4-5)

While this was going on

they all heard a door opened and the voice of the Holy Spirit (Asc. Is. 6:6)

Now recall the passages on pneumatic gifts in 1 Corinthians where Paul gives guidance and encouragement to his Spirit-filled congregation regarding the gifts of the Spirit and especially prophecy. In the church at Corinth we are again among a gathering of Spirit enthusiasts. But apart from this general affinity there are three texts in particular in which the Vision of Isaiah shows through.

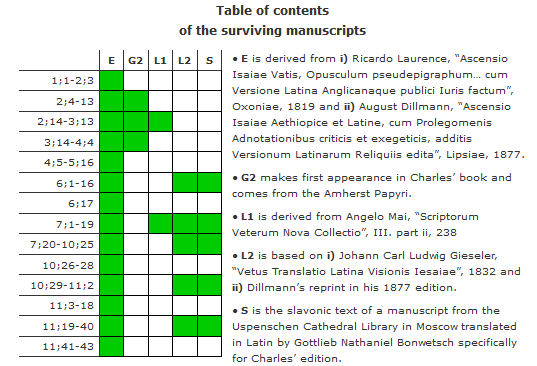

(One last preliminary: Please note that when I refer to the Vision in this post I am also including the so-called “pocket gospel” as part of it. It is found at 11:2-23 of the Ethiopic [E] and first Latin [L1] versions of the Ascension of Isaiah. For reasons that will become clear as we go along I am willing to accept that it was part of the text that the Pauline interpolators knew.) Continue reading “Revising the Series “A Simonian Origin for Christianity”, Part 1″