“Jesus and Dionysus in The Acts of the Apostles and early Christianity” by classicist John Moles was published in Hermathena No. 180 (Summer 2006), pp. 65-104. In the two years prior to its publication the same work had been delivered orally by John Moles at Newcastle, Durham, Dublin, Tallahassee, Princeton, Columbia, Charlottesville and Yale.

“Jesus and Dionysus in The Acts of the Apostles and early Christianity” by classicist John Moles was published in Hermathena No. 180 (Summer 2006), pp. 65-104. In the two years prior to its publication the same work had been delivered orally by John Moles at Newcastle, Durham, Dublin, Tallahassee, Princeton, Columbia, Charlottesville and Yale.

The names Moles thanks for assistance with this work are many: Loveday Alexander, John Barclay, Stephen Barton, Kai Brodersen, John Dillon, Jimmy Dunn, Sean Freyne, John Garthwaite, Albert Henrichs, Liz Irwin, Chris Kraus, Manfred Lang, Brian McGing, John Marincola, Damien Nelis, Susanna Phillippo, Richard Seaford, Rowland Smith, Tony Spawforth, Mike Tueller and Tony Woodman.

John Moles begins his article with two questions. The first of these is a dual one:

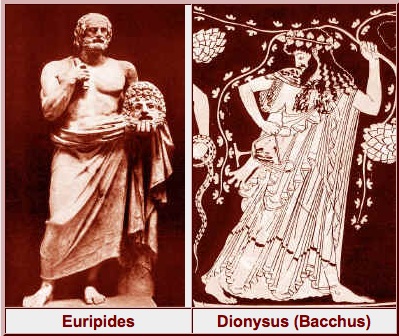

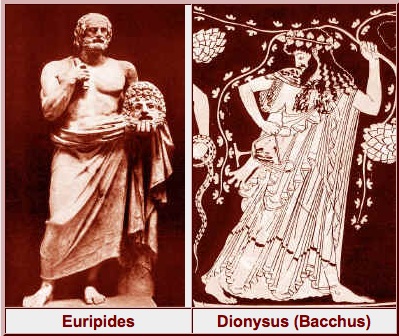

Is Acts influenced by Dionysiac myth or ritual and does it quote the play Bacchae?

Old questions, yes, but they are still being raised in the literature, as Moles indicates with the following list:

E.g. Nestle (1900); Smend (1925); Fiebig (1926); Rudberg (1926); Weinreich (1929) ; Windisch (1932); Voegeli (1953); Dibelius (1956) 190; Hackett (1956); Funke (1967); Conzelmann (1972) 49; Colaclides (1973); Pervo (1987) 21-2; Tueller (1992); Brenk (1994); Rapske (1994) 412-19; Seaford (1996) 53; (1997); (2006) ch. 9; Fitzmyer (1998) 341; Dormeyer-Galindo (2003) 49 ff.; 95; 365; Hintermaier (2003); Lang (2003); (2004); Weaver (2004); Dormeyer (2005).

The second question is the one that is the main point of the article and the one given the most space in answering:

If the answers to the above are affirmative, what are the consequences?

I have it on authority that John Moles is not a mythicist so those who read this blog with a jaundiced eye can look elsewhere for material that serves their agenda.

Broad thematic parallels between Acts and Bacchae

John Moles lists the following:

- the disruptive impact of the ‘new’ god

- judicial proceedings against the ‘new’ god and his followers

- ‘bondage’ of the ‘new’ god or his followers

- imprisonments of the ‘new’ god’s followers

- their miraculous escapes from prison

- divine epiphanies

- warning that persecution of the ‘new’ god or his followers is ‘fighting against god’

- a direct warning by the unrecognized ‘new’ god to his persecutor

- ‘fighting against god’ by the ‘new’ god’s persecutor

- ‘mockery’ of the ‘new’ god or his followers

- general human-divine conflict

- kingly persecutors

- a kingly persecutor who arrogates divinity to himself

- divine destruction of impious kingly persecutor

- rejection of the ‘new’ god by his own, whom he severely punishes

- the destruction of the palace/temple

- adherence of women to the ‘new’ religion

- Dionysiac ‘bullishness’

Though some of these parallels need justification, as Moles points out, it is clear that the two texts “share numerous important themes”. The possibility that the Bacchae influenced Acts is thus not implausible.

Detailed thematic parallels between Acts and Bacchae

Moles lists three “crucial cases”. Continue reading “Jesus and Dionysus in The Acts of the Apostles and early Christianity”

Like this:

Like Loading...